The Guggenheim’s Futurism exhibition and the Whitney Biennial offer competing visions of present-mindedness.

Barry Schwabsky

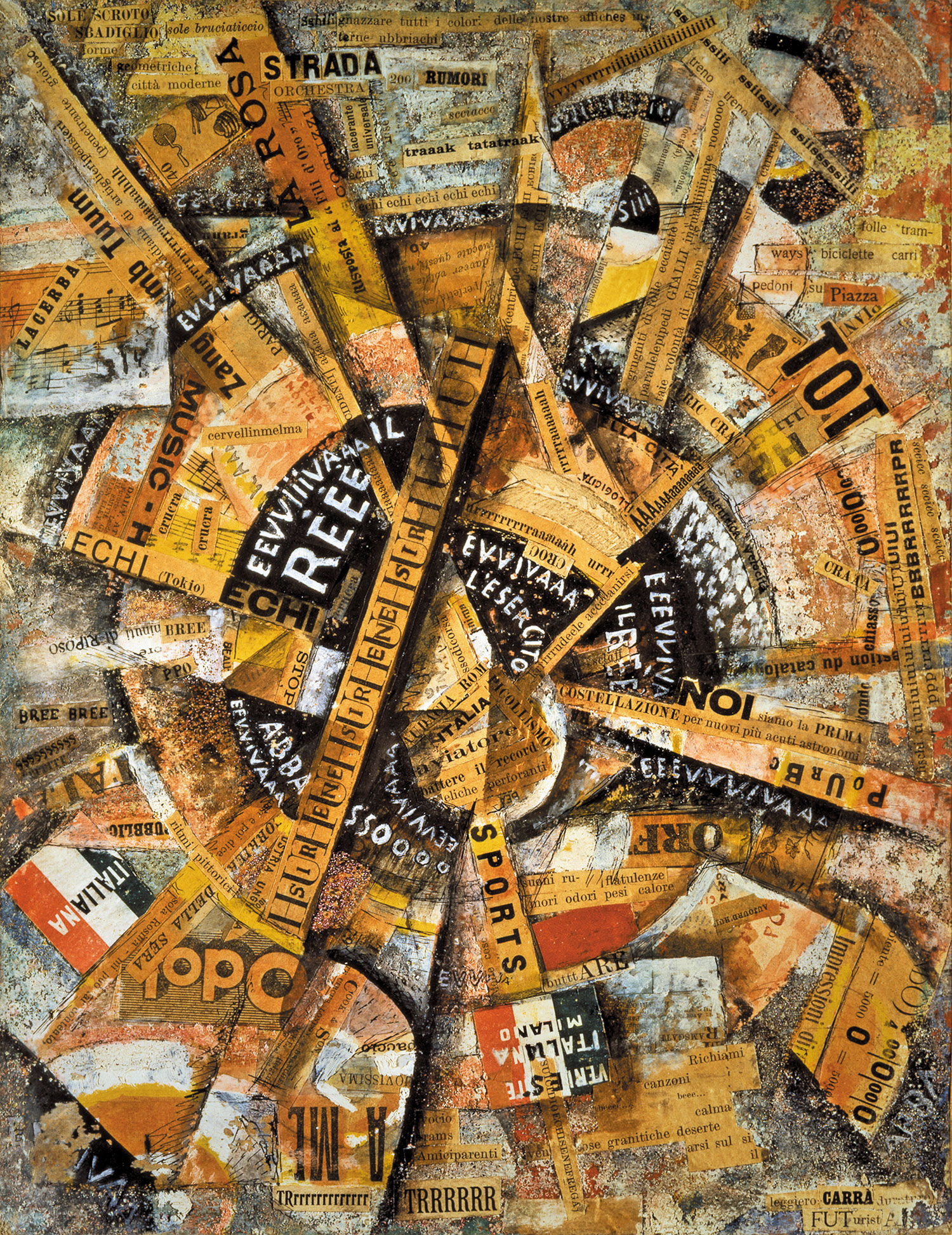

Interventionist Demonstration (Manifestazione Interventista), 1914, by Carlo Carrà

For years I’ve been hearing it said that young artists think art began with Andy Warhol. It’s never been true. But now what I hear is art historians complaining that none of their students want to study anything but contemporary art. Among young art historians, it seems, to delve as far back as the 1960s is to be considered an antiquarian. “They only take my courses because they think they need some ‘background,’” one Renaissance specialist told me. “We have to accept almost anyone who applies saying that they want to study anything before the present, just to give our current faculty something to do.” What a time, when the art historians have less historical consciousness than the artists—and no wonder that the former, these days, show so little interest in what the latter actually do.

When I was a grad student (in a different field), the budding art historians I knew were studying medieval, they were studying mannerism, they were studying the Maya. No one thought of studying living artists. The most adventurous ones might be investigating Italian Futurism. Now the Futurists seem as distant as the Maya. But might this be their own fault? They were the artists, after all, who vowed to “destroy the museums, libraries, academies of every kind”—to unburden themselves of the dead weight of culture and history. The Futurists meant to be men of action; and, following Nietzsche (who warned in his Untimely Meditations that the knowledge of history presented more disadvantages than advantages for life), they believed forgetting to be its inescapable prerequisite. “As the active person, according to what Goethe said, is always without conscience, so he is also always without knowledge,” the philosopher taught. “He forgets most things in order to do one thing; he is unjust towards what lies behind him and knows only one right, the right of what is to come into being now.” Filippo Tommaso Marinetti made the point more succinctly in a 1909 manifesto, already waving away the objection that his belligerent posture was nothing new: “Who cares? We don’t want to understand!”

The museums, the libraries and the academies are still with us, but their keepers are increasingly beguiled by the present and would like to become its curators, librarians and scholars. They are no longer “passatists,” but neither are they Futurists, for Futurism was still beset by historical consciousness; the Futurists’ fear and hatred of the past—a fear and hatred of their own potential weakness in its face—is another thing altogether from the indifference of today’s presentists, for whom it really might be true, as the Futurists vainly boasted, that “Time and Space died yesterday. We already live in the absolute, because we have created eternal, omnipresent speed.”

Would the Futurists have recognized the eternal speed of the Internet as the future they had envisioned? I doubt it. The galaxy of eyeballs glued to smartphones has little in common with the “great crowds excited by work, by pleasure, and by riot” of whom Marinetti promised to sing. Only our data—and not we ourselves, it would appear—stream forth in the “polyphonic tides” of fervent commotion that he dreamed of, and that Umberto Boccioni evoked in early masterpieces of Futurist painting like Riot in the Galleria (1910), The City Rises (1910–11) and Simultaneous Visions (1911), or that Carlo Carrà summoned in his astonishing Funeral of the Anarchist Galli (1910–11). On the other hand, perhaps Marinetti’s knack for creating buzz truly was ahead of its time. He proclaimed the birth of a movement, in advance of the production of any of its works, with a burst of propaganda; one senses he would have instinctively understood the ways and means of viral marketing. And the Futurists would surely have taken satisfaction in today’s cult of youth and the feeling that the velocity of change has rendered experience worthless. Largo ai giovani! the Futurists demanded: “Make way for the young!” And then, Marinetti predicted, “When we are forty, other younger and stronger men will probably throw us in the wastebasket like useless manuscripts—we want it to happen!”

* * *

Whatever one’s doubts regarding the relevance of Futurism to art today, the present exhibition at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York, “Italian Futurism, 1909–1944: Reconstructing the Universe”—on view through September 1—is the largest and most comprehensive presentation of the movement ever held in this country and, as such, is indispensable for anyone interested in artistic modernism. The irony involved in the museum’s embrace of the putative museum-wreckers has long been noted and is almost too obvious to mention. Even by 1929, as exhibition curator Vivien Greene points out, “the movement that had despised the academy saw its leader, Marinetti, become a member of the Academy of Italy.” But it should be added that Futurism might seem a bit less like just another tombstone in history’s cemetery were it not presented, as it is here, as mainly an affair of painting (and a bit of sculpture). Even the best work of the Futurist painters (Boccioni and Giacomo Balla among the early adherents, Fortunato Depero among the second wave of recruits) is pretty thin stuff compared with the likes of Picasso, Matisse, Duchamp, Mondrian, Malevich and a dozen others among their contemporaries working elsewhere in Europe. Putting Futurism’s animating literary and political ideas aside, the paintings, for the most part, simply lack body; they don’t live on the canvas. Despite their modernist styling, most are still really conceived of as old-fashioned pictures, depicting great events taking place elsewhere rather than embodying events in themselves.

Yes, Greene and her colleagues have tried to be expansive in presenting all the other dimensions of Futurist creativity—graphic design, architecture, fashion, furniture, photography, cinema, music, performance and poetry (especially that new form of visual poetry the Futurists dubbed parole in libertà , or “words in freedom,” with its letters scattered higgledy-piggledy across the page) among them. It is in some of these domains that the Futurist endeavor still seems to contain clues worth following. And they’re all present and accounted for here—more convincingly so, I might add, than the same side ventures (as one had to see them) were in last year’s equally grand-scale MoMA exhibition “Inventing Abstraction, 1910–1925: How a Radical Idea Changed Modern Art.” And yet, except to the extent that they can be credibly shown flat in a frame or a vitrine, they remain elusive: every sort of printed matter looks great, and carries more of its original electrical charge than all but a handful of the paintings, but how would it have ever been possible to re-create the Futurist serate, or evenings, that are as near as we can get to a point of origin for what today is called “performance art”? These events could include poetry, noises (also known as music) and anything else that came to mind, but less important than what took place onstage was the effect it would have on the public. Marinetti hymned “the pleasure of being booed,” and he knew it intimately. “Spurred on by the Futurists themselves,” as Claudia Salaris writes in the exhibition catalog, “the audience often reacted by hurling fruit and vegetables and other projectiles at the performers. The encounters frequently ended with police intervention; the following day, the event would appear in the newspapers, thus guaranteeing publicity.” Imagine that taking place at the Guggenheim!

Still, a second-rate picture could hardly hope for a better resting place than the Guggenheim’s Futurism exhibition. At least one can finally understand these artists, and almost begin to empathize with the pictorial timidity beneath the rhetorical bravado—and also with the simple desire to make life more fun that stimulated so much of this hectic activity. “Nell’aldilà mi voglio divertire,” wrote that least Futurist of Italian poets, Eugenio Montale, in one of his last poems: “In the afterlife I want to have fun.” Well, in this graveyard the ghosts are still living it up. For us viewers, by contrast, the pleasures at hand are of a more studious sort. One of the signal achievements of this exhibition is that, rather than concentrating on the period of Futurism’s inception and greatest energy—that is, from the publication of the first manifesto in 1909 through the years of World War I—it traces the movement all the way to Marinetti’s demise in 1944. As a result, the show features artists and works nearly unknown outside Italy, and sometimes half-forgotten even there. If none can be counted a major rediscovery, still, Depero at least is never uninteresting, and Enrico Prampolini’s polimaterici—assemblages of diverse materials—begin, however weakly, to envision the surface of the work as a substantial reality rather than a view onto an imaginary vista, and thereby look forward to the best art of postwar Italy. Lucio Fontana or Alberto Burri would have appreciated a work like Prampolini’s aptly titled Interview With Matter (1930).

However curious it is to follow the trajectory of Futurism through the 1920s and ’30s, where few but specialists have followed, it is impossible to ignore that the whole exhibition is structured as an anticlimax, beginning as it does with Futurism’s highest moment, in which it transcends itself and becomes something quite other. The first room of the show is devoted to the three great sculptures Boccioni produced in 1912 and ‘13, works in which he shows himself to have understood the lesson of Picasso and Braque’s Cubism more deeply than any of the other Futurists and in which he made something completely original from it. The first of them, Development of a Bottle in Space (1912), turns the Futurist cliché upside down: it shows not the trajectory of a person or object through space, but the Heraclitean movement of an object completely still. Antigraceful (1913) presents the head of an elderly woman, the artist’s mother, as if cut up and recombined (along with a few foreign elements), yet still imbued with tenderness as well as humor.What better rejoinder to his colleagues’ belief that only the vitality of youth and the deeds of men of action are worth limning? Finally, in Unique Forms of Continuity in Space, also from 1913, Boccioni returned to a more expected Futurist subject, a man striding forward—but not with speed or freely scattering energies, as one might have expected. The fluid, rippling forms that make up this strange body are not its own; what Boccioni shows us, I believe, is the air moving around and about it as the body steps forward, seemingly against some great resistance. Boccioni’s man has no shape of his own, but is molded instead by those forces in the face of which he determinedly proceeds.

* * *

Biennials are generally supposed to be reports on the present, but they have become more and more concerned with the past. The last Documenta, in 2012, included figures such as Giorgio Morandi, Lee Miller, Emily Carr and Charlotte Salomon in its attempt to define the contemporary. The current Whitney Biennial (on view at the Whitney Museum of American Art through May 25) may not reach quite as far back as to those figures, but a sense of retrospection lingers over much of the show.

Two years ago, the Biennial included an impressive freestanding exhibition of works by Forrest Bess, the legendary Texas painter who died in 1977, curated by Robert Gober. This time around, there are many such moments. Richard Hawkins and Catherine Opie have curated a selection of iconlike mixed-media paintings by Tony Greene, a relatively little-known Californian who died young of AIDS in 1990. Philip Vanderhyden has re-created a massive 1988 wall sculpture in painted vinyl and neon by Gretchen Bender, an artist best known for her work in video, who died of cancer in 2004. Two more artists lost to AIDS, Martin Wong (1946–1999) and David Wojnarowicz (1954–1992), are re-presented by Julie Ault, both through works taken from the Whitney’s collection and documents borrowed from the Downtown Collection at New York University’s Fales Library. Joseph Grigely presents an archive of materials relating to the life and career of Gregory Battcock, the art critic and editor (best remembered for a pioneering 1968 anthology of writings on Minimalism), who was murdered in 1980.Another archive is the work of Public Collectors, a Chicago-based collaborative project led by Marc Fischer, whose subject here is Malachi Ritscher, a musician and activist who documented the Windy City’s lively free-jazz and experimental-music scenes in thousands of live recordings until his death in 2006, after setting himself on fire to protest the war in Iraq. And finally, there’s a selection of notebooks from the novelist David Foster Wallace, who committed suicide in 2008.

It all adds up to a reminder that, even as the art historians have been slowly trying to squeeze the history out of their discipline, artists have been assiduously turning themselves into historians, archivists, even collectors of a sort. Stylistically, much of the new art has its eye on the past, and is not necessarily the worse for that. Dawoud Bey’s black-and-white portrait photographs—haunted by the bombings in Birmingham, Alabama, in September 1963—have been made with the sober yet empathetic eye of an August Sander; Alma Allen’s biomorphic sculpture looks back to Arp and Brancusi; Susan Howe’s cut-up visual poetry (a distant and more ruminative descendent of the Futurists’ parole in libertà) seems to be attempting a literary séance. “Archives, the material—the fragment, the piece of paper,” Howe has said, “is all we have to connect with the dead.” This is more than just retro styling. There must be a terrible feeling abroad that no one but an artist is going to salvage any sense of memory, and that since, as Walter Benjamin put it, “the past carries with it a secret index by which it is referred to redemption,” our stubborn present-mindedness may represent the loss of some last chance.

This year, the selection of artists for the Biennial has been entrusted to three people, none of them Whitney employees. Anthony Elms is a curator at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Philadelphia; Stuart Comer has recently arrived as chief curator of media and performance art at MoMA after having worked for many years at the Tate Modern in London; and Michelle Grabner is a Chicago-based artist and critic who (with her husband, Brad Killam) runs two exhibition spaces, the Suburban (originally the garage behind their home in Oak Park) and the Poor Farm in rural Wisconsin. The three curators did not work together as a committee; each has his or her own floor. What’s strange is how nearly interchangeable the artists seem from floor to floor. Yes, Elms’s second floor seems a little more political, Comer’s third floor is a bit more evocative of queer identity, and Grabner’s fourth floor is heavier on women abstract painters; but even a significant amount of reshuffling might have left the floors feeling substantially the same. It’s as though each curator felt compelled to act as a committee of one and accommodate as much of the contemporary art spectrum as he or she could. I understand the impulse, but it blunts the point of having three curators work independently. It might have made for a more challenging (and more productively divisive) exhibition if each of the three had chosen to examine in depth just a handful of distinct tendencies in the contemporary scene, or even to focus on a single one exclusively. For instance, I’d love to have seen a whole floor of Grabner’s choice of women abstractionists (and quasi-abstractionists), all by themselves and with a lot more space for their work to breathe in—and, above all, with a lot more work from each artist. I’m crazy about Dona Nelson’s two-sided free-standing paintings and would have liked to see more than just a pair of them. And why only one work apiece from Molly Zuckerman-Hartung and Suzanne McClelland, two painters who embed language in their abstractions; why not show the breadth of their recent work instead? And I’d have the same question about quite a few of the other artists.

Whatever my misgivings about the structure of this year’s Biennial, it features a lot more good and substantial work than it did two years ago, in a show that was wildly overrated by many critics. Maybe one reason for the frantic praise was that show’s sparse installation; with the work of many fewer artists on view than this time around, when there are no less than 103, one could fully grasp what was there and focus on it more clearly. But just as was the case two years ago, I can’t get over the feeling of an art world becalmed, and not only at the Whitney—other big exhibitions, such as the 2012 Documenta, gave the same sensation of art at a standstill. But as Boccioni’s bottle reminds us, stasis also has its hidden inner movements and tensions. There’s some powerful work being made these days, and a good bit of it is here at the Whitney; but as an ensemble, it seems smaller than the sum of its parts.

The Futurists believed themselves to be riding and even somehow pushing forward a wave of progress that was bigger than they were as individuals; three decades later, as Europe was tearing itself to bits, Benjamin feared that “what we call progress” was instead an endless catastrophe. Today, we have our own reasons for thinking the same. Artists are searching for clues in the recent past, trying to imagine how to proceed in the absence of a common project based on faith in progress. Without that, museums can seem more than ever what Marinetti proclaimed they were: “public dormitories where one lies forever beside hated or unknown beings…absurd abattoirs of painters and sculptors ferociously slaughtering each other with color-blows and line-blows, the length of the fought-over walls.” (Benjamin called this “historicism’s bordello.”) Yet one day, all these beautiful sleepers may awake. Certain works here are somehow more compelling than the context from which they emerged—and in which they have been buried in turn. Who will light the fuse thanks to which they will be blasted, as Benjamin hoped, “out of the homogenous course of history”?

Barry SchwabskyBarry Schwabsky is the art critic of The Nation.