There have been few personalities in architecture as vexing, complex, and influential as Philip Johnson. Born in Cleveland in 1906, Johnson was heir to a vast stock-market fortune. From his education at Harvard to the height of his career, designing skyscrapers for some of America’s largest companies, Johnson was aided by both his money and his vast social circle, becoming one of the most powerful and polarizing men in the history of the field. His architectural expression underwent dramatic stylistic transformations, from a consummate Miesian modernism to a polemical postmodernism; in the 1970s and ’80s, Johnson’s corporate skyscrapers seemed to pop up in every major city in America, for better or for worse.

“Johnson was a historicist who championed the new, an elitist who was a populist, a genius without originality, a gossip who was an intellectual, an opportunist who was a utopian, a man of endless generosity who could be casually, crushingly cruel.” This is how Mark Lamster’s new book, The Man in the Glass House, introduces its subject, setting the stage for a biography that not only raises the bar for writing with nuance about difficult historical figures, but also offers an eye-opening glimpse into architecture’s transformation from a staid and upwardly mobile white-collar profession to the deeply unequal and star-studded spectacle it is today. Glass House tackles the myths and enigmas of Johnson’s life, and of a supposedly egalitarian architectural culture, in one fell swoop. As Lamster concisely puts it: “We cannot not know Philip Johnson’s history because it is our history—like it or not.”

Johnson began and ended his career as a power broker. In his 20s, fresh out of Harvard, he joined the newly established Museum of Modern Art in New York as a curator, helping to found its department of architecture. A consummate socialite, he had an impeccable sense of taste and a cunning wit, both of which were necessary when dealing with the art world. With his keen eye for contemporary artists, Johnson was responsible for the purchase or donation of several of MoMA’s most iconic pieces, including Jasper Johns’s Flag and Andy Warhol’s Gold Marilyn Monroe.

One of Johnson’s important early contributions was bringing the work of contemporary architects—primarily Walter Gropius, Mies van der Rohe, and Le Corbusier, as well as Americans like Frank Lloyd Wright—to the museum, giving the field broader public exposure and sealing its place among the fine arts. His “Modern Architecture: International Exhibition” in 1932 successfully sold the profession to America by reducing and reframing the architecture of the day into an aesthetic that would come to be known as the International Style. And in his curating, he conveniently omitted architectural modernism’s more populist programs and ideology (the building of affordable housing, schools, recreation centers, and the like). In fact, Johnson, who could afford to fund his own projects and work on commissions for free (a significant advantage over his competitors), had little care for social concerns unless they somehow benefited him: “Social responsibility was boring,” Lamster notes,” and for Philip Johnson, to be boring was an unforgivable crime.”

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

Johnson’s later exhibit for MoMA, 1934’s “Machine Art,” put everyday objects on display—an entirely new idea, and one that thrust industrial design to the artistic forefront. This radical display of everything from ball bearings to the automobile was an innovation in that it included objects from domestic life in the canon of design; but it also created a culture that equated design with commercial commodity, with the art museum as its supermarket of choice. His earliest work changed the very rules about what artistic practices could be included inside museum walls, but, in pure Johnson fashion, he helped create through these very exhibits the bloated art marketplace we now live with today.

A chunk of The Man in the Glass House is devoted to a complete and damning exposition of Johnson’s affiliation with fascism. Johnson’s fascist past is a common architecture-school topic of discussion, but the true extent of his participation in fascistic movements is revealed here in horrifying detail. Johnson’s political activities included his leaving MoMA to join Louisiana populist strongman Huey Long’s political campaign in an effort to eventually undermine it and later spending time with with the anti-Semitic radio preacher Father Charles Coughlin who was, at the time, in the process of building a fascist political party. They later expanded beyond the American scene to include trips to Nazi Germany (he even spent time in Poland as a “journalist” during the early days of the German invasion) and, later, the circulation of Nazi propaganda in the United States as an unpaid agent of the German state.

Johnson’s fascist beliefs endured well past his youthful dalliance and into the architect’s middle age. His architecture, too, seemed to toy with fascist motifs. Of one example, the 1964 Beck house in North Dallas, Lamster writes: “The Becks got the iconic design they wanted, but perhaps did not realize that the arcaded facade rather overtly referenced the Palazzo della Civiltà Italiana, in Rome—a monument to Mussolini’s fascist experiment.”

Once more, it was Johnson’s money and powerful connections to the donor class (including the Rockefellers) and the art and museum establishments that enabled him to be forgiven and welcomed back into the fold of the New York cultural elite with little consequence. He was never once publicly confronted with the full extent of his racist and anti-Semitic activities, which he doggedly tried to divert attention from by profusely apologizing, citing his Jewish friends and his work (including a nuclear facility) for the state of Israel.

The role that Johnson’s personal fortune played in shaping the architecture world is perhaps the most revealing aspect of Lamster’s book, and the unscrupulous ways that Johnson used his power paint a clear picture of how architecture got to be what it is today: a dual world comprising a cluster of big-name firms taking commissions from the likes of Saudi oil princes and billionaire investors, and the actual lives of most architects, who like so many other white-collar workers must deal with a race to the bottom in terms of declining wages (including unpaid internships), the debts incurred from an expensive professional education, long hours, and little credit.

Lamster reveals in great detail how Johnson, in collaboration with a small number of powerful cultural institutions (and the billionaires that funded them), determined who would become the next generation’s architectural stars. Little by little in Lamster’s book, the hoary narrative—still bafflingly predominant in today’s architecture world—of the scrappy young draftsman pulling himself up by his bootstraps to become a great architect through hard work and talent is relentlessly dismantled.

Johnson, as an institutionally supported tastemaker and member of the donor class, not only exercised control over his own career but was directly responsible for instigating both the major careers and the major upsets of 20th-century architecture (while deriving much notoriety and glee from the latter). Lamster describes the many parties and social occasions at which Johnson gathered and groomed the up-and-coming hotshots; being in his good graces helped secure commissions that kick-started the careers of some of architecture’s biggest celebrities, including Michael Graves, Robert A.M. Stern, and many more. His influence also extended into the realm of theory and architectural education: He bankrolled Robert Venturi’s Complexity and Contradiction, the book that provided postmodernism with its theoretical foundation. It was truly the boys’-club era of architecture, one in which very few women and minorities were allowed. And this boys’-club culture has now come full circle with the “Shitty Men in Architecture” list, on which a number of Johnson’s protégés, such as Richard Meier were outed.

The critical way in which Lamster handles Johnson’s role in the architectural movements of the late 20th century is particularly frank and refreshing, and demonstrates his prowess at connecting the architecture of the recent past to our current dilemma. Crucially, Lamster links postmodern architecture’s semi-ironic invocation of traditional elements to the political conservatism of the time:

[T]hat was the look of the moment in the burgeoning Reagan era. It was morning in America, and Johnson’s solid buildings, with their familiar architectural elements—columns, pediments, vaults, gables, and so many other details jettisoned as extraneous by modernists—spoke to a conservative clientele open to a corporate language that corresponded to the white-picket-fence suburbs to which they returned after work.

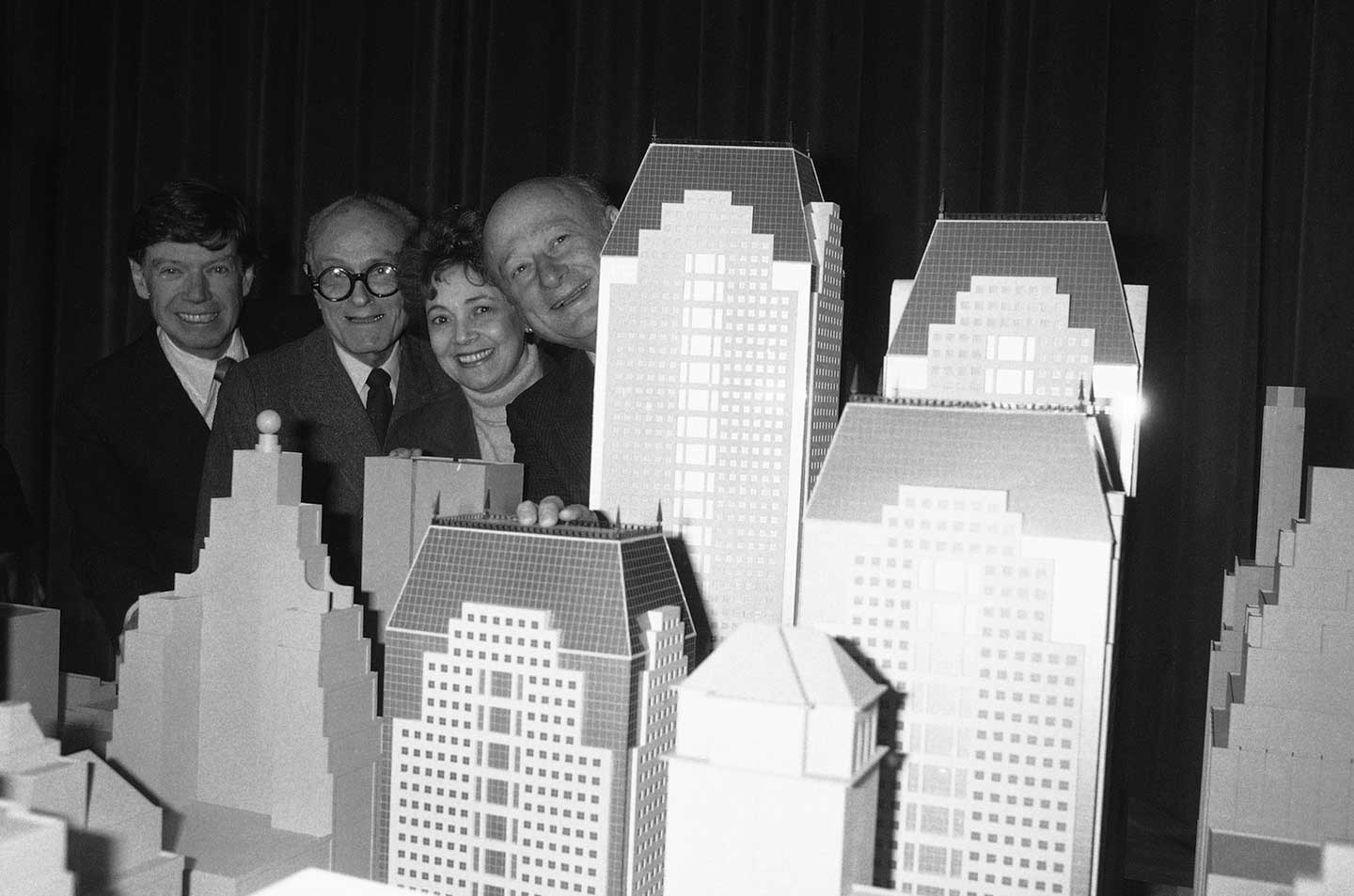

In Johnson’s life, we can see this distinct shift in architecture mirrored in his own move away from cultural institutions and their patrons toward working directly with the corporations themselves. With the help of his business partner John Burgee, Johnson made the leap from designing museums and private houses to designing skyscrapers and corporate headquarters in cities throughout the land. The changing style of Johnson’s work at the time reveals his keen understanding of the shift in corporate taste: His earlier such work (and arguably his best), the late-modernist IDS Tower in Minneapolis and the Pennzoil Place complex in Houston, morphs in the mid-’70s and early ’80s into the campy (but admittedly lovable) postmodern AT&T Building in New York and the glass turrets of the Pittsburgh Power and Gas Tower—literally a corporate castle built for the rule of a new, neoliberal generation of the business elite.

Later, when Deconstructivism—the explosive, gravity-defying style defined by buildings like the Guggenheim Bilbao in Spain and the Jewish Museum in Berlin—came into vogue, Johnson helped curate (with theorist Mark Wigley) another MoMA exhibition that pushed architecture even further into an elitist, celebrity-obsessed, and market-driven mode. Lamster describes how the curators chose to eschew the radical philosophical basis of the movement in favor of vaulting yet another predetermined gaggle of architects—Frank Gehry among them—to acclaim, giving us the term “starchitecture” in the process: “For the next two decades, the profession would be defined by a chosen few jet-setting international figures building ever grander and more expensive monuments designed to capture public attention. That had always been Johnson’s goal.”

Even so, not all of Johnson’s life and contributions to the field are explicitly negative. He makes for an easy villain and a difficult protagonist, and it’s Lamster’s ability to balance the many facets and faces of Philip Johnson that makes The Man in the Glass House such a complete and compelling portrait. Here was a man whose penchant for public spectacle belied a deep insecurity; whose contributions in life and work were a murky mix of negative, positive, and nihilistic. Johnson, despite his sometimes shocking cruelty and self-centeredness, was still, to some, a lifelong friend; he was also a devoted partner to the art collector and curator David Whitney. Some examples of Johnson’s work could be expertly crafted and profoundly elegant, such as the New York State Theater at Lincoln Center and the Glass House in New Canaan, Connecticut. At other times—in the case of his buildings for Donald Trump, the Crescent in Dallas, or the University of Houston School of Architecture—it was kitschy, loud, and cynical.

Johnson’s talent and cunning as a patron, architect, and curator changed both the built environment and the way we, the public, appreciate and understand architecture. The Man in the Glass House deals with the contradictions of Johnson’s life more completely than any previous biography of the architect. Lamster deftly avoids the common practice of writing a book about architecture that dutifully moves from style to style, and building to building, in favor of one that weaves salient architectural criticism and approachable analysis into a rich story about a truly complicated person. Johnson’s life—indeed, the story of 20th-century America—is a story “of darkness as much as light; a story of inequality and bigotry, of the perils of cynicism, of human weakness and venality, of rampant corporatism, of the collapse of wealth and authority into the hands of a plutocratic class.” In The Man in the Glass House, the darkness and light are inextricable.

Correction: A previous version of this review mischaracterized Johnson’s relationship with Huey Long and Father Charles Coughlin. The piece has been updated to accurately reflect his involvement with both.