As baby boomers have begun retiring, the number of seniors in our country is ballooning—by the year 2050, the number of people 65 and over is projected to double. But the Trump administration didn’t seem to really care about this vulnerable population when it unveiled its absurd budget proposal last year. The cuts that plan laid out would have decimated programs across the country that serve our most disadvantaged, overlooked neighbors: Meals on Wheels.

Trump’s plan would have done away with $3 billion of community-development block grants, which are used in some states to support senior nutrition and home-delivered meal programs. The plan also proposed to make an 18 percent cut across the board to the federal Department of Health and Human Services, which would greatly impact the Older Americans Act Nutrition Program. That program provides 35 percent of the funding for local Meals on Wheels programs from coast to coast, and these programs empower 2.4 million seniors to enjoy healthier and more independent lives in their own homes.

Thankfully, the omnibus spending bill passed by Congress and signed by Trump last week didn’t carry through these threats. In another sign of the gap between this administration’s rhetoric and its ability to actually govern, the bill actually included increases for programs like Meals on Wheels that assist seniors.

Citymeals on Wheels, operating in New York City, is one of more than 5,000 home-delivery meal programs across the country. There are now over 1.4 million people over the age of 60 in New York City, and Citymeals on Wheels, a private/public partnership with the New York City Department for the Aging, delivers over 2 million meals to more than 18,000 elderly residents every year, in all five boroughs.

At Encore in Manhattan’s Theater District, one of 30 senior centers Citymeals partners with to prepare and deliver their meals, the cooking starts early: Chefs begin prepping before dawn to get meals out the door by 9:30 in the morning. Encore, a provider of a range of social services for seniors since 1977, also hosts two lunch sessions on-site: The menu changes each month and meets strict nutritional standards mandated by the state. Once the food is prepared, it’s sealed, labeled, and packaged for delivery—a chaotic, yet well-orchestrated scene. Meal carts are then loaded into delivery vans and each meal deliverer is dropped off to distribute their approximately 30 meals within a four-block radius, no matter the weather. All of this depends on a mixture of employees and volunteers.

Last year I was invited to shadow Encore employee Natasha Vanderhorst on her meal-delivery route. “My grandma was really up in age, and I said you know, it would be nice to do something for the seniors,” she told me when I asked her why she chose to become a meal deliverer. “So, I thought I would take a chance at it.” Eight years later and Natasha is still delivering more than 30 meals a day, six days a week. For the past five years, Natasha’s children, Tony, Elizabeth, and Robert, have been volunteering with Encore during the summer months and school breaks as well, preparing cold packs, adding nutrition labels to hot meals, and anything that needs to get done—Tony just recently became a full-time employee as a dishwasher.

Natasha’s job is physically demanding and at times heartbreaking. Unlike in other boroughs, Citymeals deliverers in Manhattan distribute meals on foot, navigating their carts through the crowded streets and sidewalks of New York City. Not all apartment buildings have elevators—in fact, Natasha has four walk-ups on her route, but she doesn’t mind, because “it’s for the seniors.” There’s also an emotional toll when someone passes away, because “Once you get to know a client, you fall in love with them.” Natasha lost four clients just this past year.

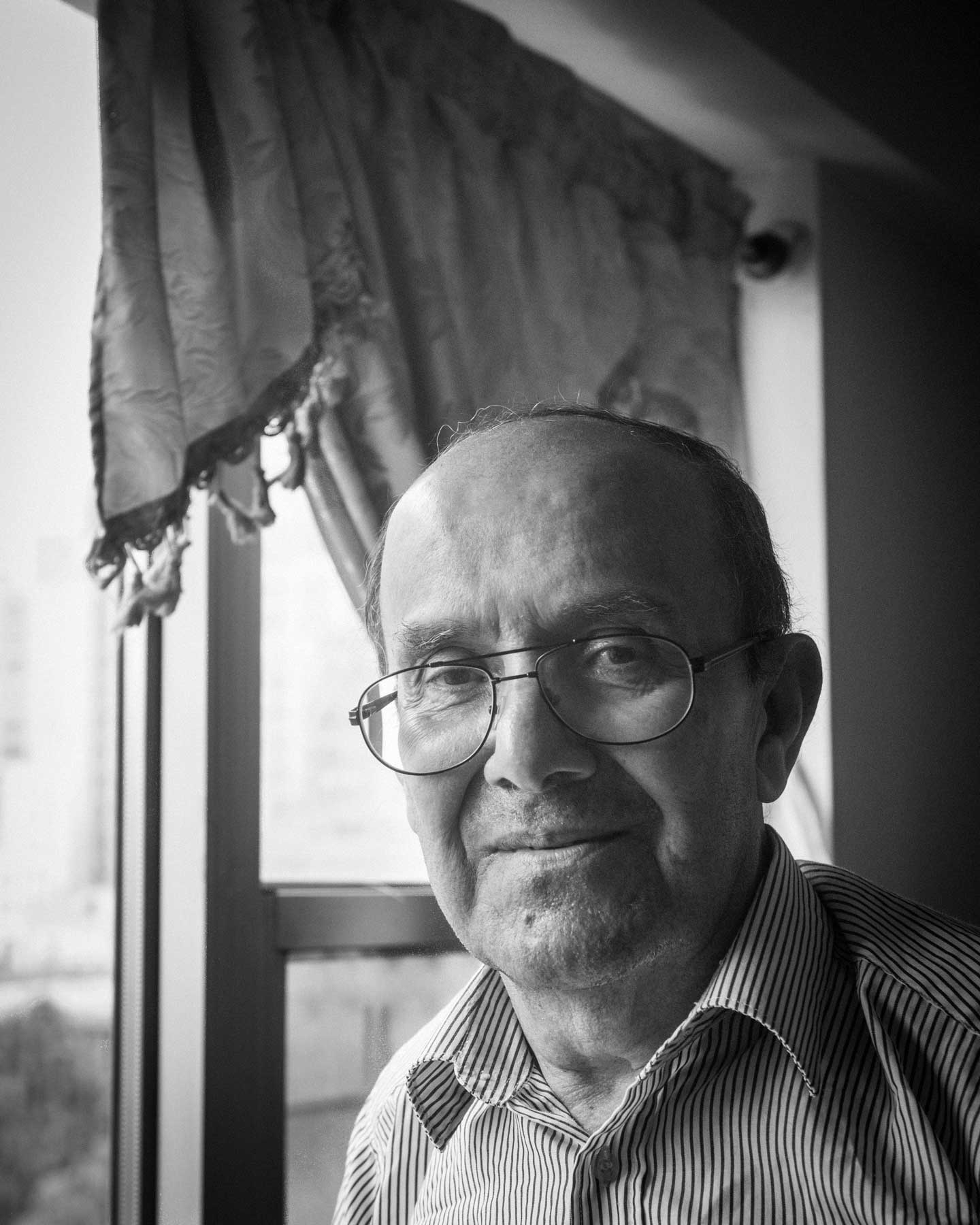

As we reach the last meal recipient on her list, Natasha knocks on the door belonging to Felix Nogueras with the cry, “Meals!” Mr. Nogueras, now in his 75th year, answers the door with a smile and invites us inside his small, light-filled, 9th-floor Chelsea apartment. For the past four years, Monday through Saturday, Mr. Nogueras has been receiving a fresh hot meal and a cold pack with fruit and milk from Natasha every day around 11 am—on Saturdays he gets two servings of the cold pack plus a frozen meal as well, to cover Sunday. Since his father passed away, Mr. Nogueras has lived alone and is grateful to Natasha not only for her timely delivery of the meals but also for the fact that she is one of the few people who regularly check in on his well-being.

At the age of 4, Mr. Nogueras moved to New York City from Puerto Rico, and he has lived here ever since. During our visit he told us about a city of harsher economic times where, as a teenager, he earned 25 cents a shoe shine to help his mother who, while working full-time in the garment district, was raising three children on her own. He’s had a number of other jobs since then, from healthcare to education, but they’ve all focused on helping others. Mr. Nogueras finally retired a few years ago after a 15-year tenure as a student counselor at DeWitt Clinton High School in the Bronx, where he was instrumental in establishing and managing a ground-breaking program, in partnership with Montefiore Medical Center, that provides clinical services to students such as general check-ups and dental, as well as specialized medical care for pregnant teens, teen mothers, and their children.

Several years ago, just before he retired, Mr. Nogueras was diagnosed with prostate cancer and hospitalized. But while he was receiving treatment, he was told that he would actually require immediate surgery for an unknown ailment, which resulted in the complete amputation of his left foot and all but one of the toes on his right. After surgery, he was confined to a wheelchair, but this didn’t stop Mr. Nogueras. With perseverance and dedication, he slowly learned to walk again, first with the assistance of a cane and then completely on his own with the support of his specialty-made orthotic shoes—these enable him to move around freely, but their lack of grip pose potential dangers when even the slightest fall can cause serious damage to an aging body. This is again where Citymeals comes in—alleviating stress and making it easier to live a full life without injury.

Heava Lawrence-Challenger and her daughter Tiffany Challenger have been volunteering with Citymeals for the past six years—just two of the 21,152 volunteers who provide nearly 67,775 hours of service every year through the program. Every Saturday, despite their busy schedules, they make the hour-and-a-half journey from their Co-Op City apartment in the Bronx to a community center in the Upper East Side where they collect meals for delivery. Heava works full-time as a senior professional skills trainer for New York City’s Department for the Aging, and Tiffany is a junior at Democracy Prep Endurance High School, Girl Scout ambassador, and volunteer with several other charitable organizations—they make good use of the long travel time, catching up on each other’s active lives.

After delivering meals to about 13 home-bound seniors, they then make the trek back to Co-Op city, where they spend their afternoon visiting with Harriet Ross—they were connected with her through another Citymeals on Wheels initiative that pairs volunteers with their isolated elderly neighbors. Heava, Tiffany, and Mrs. Ross can spend hours chatting, watching TV, and sometimes attending community events or concerts. Living within a five-minute walking distance allows them to maintain such a close relationship, providing an extra sense of comfort and security for Mrs. Ross—with whom they have built a loving friendship over the past four years.

Mrs. Ross, born and raised in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, has spent her entire 86 years in New York City—her Russian father came through Ellis Island before the turn of the 20th century. She lived through some of the city’s toughest years, and enjoys regaling Heava and Tiffany with stories from her past.

“I think [these programs] are so great for teens, because they get to meet these seniors who have such history,” Heava told me. “Tiffany has heard about what it was like to work in New York as a woman in the early ’60s, working in the garment factories, living in Brooklyn, the Bronx. Some children will never get that firsthand knowledge.”

Osteoarthritis makes it difficult for Mrs. Ross to get around: She now uses a wheelchair to maneuver her intimate 17th-floor apartment where she has lived for the past 30 years after her husband’s death. Mrs. Ross is charming, and her home warm and welcoming—hugs are offered to all who visit. She loves people, but because of her lack of mobility, her interactions are limited.

Heava and Tiffany’s relationship with Mrs. Ross goes beyond the scheduled volunteer hours—they care deeply for each another. Heava will reach out during the week to touch base, especially if there is an appointment that Mrs. Ross is worried about. “She’s like a grandmother to me” Tiffany told me, “I’m comfortable with her and I feel at home with her…and I would definitely refer to her as family.”