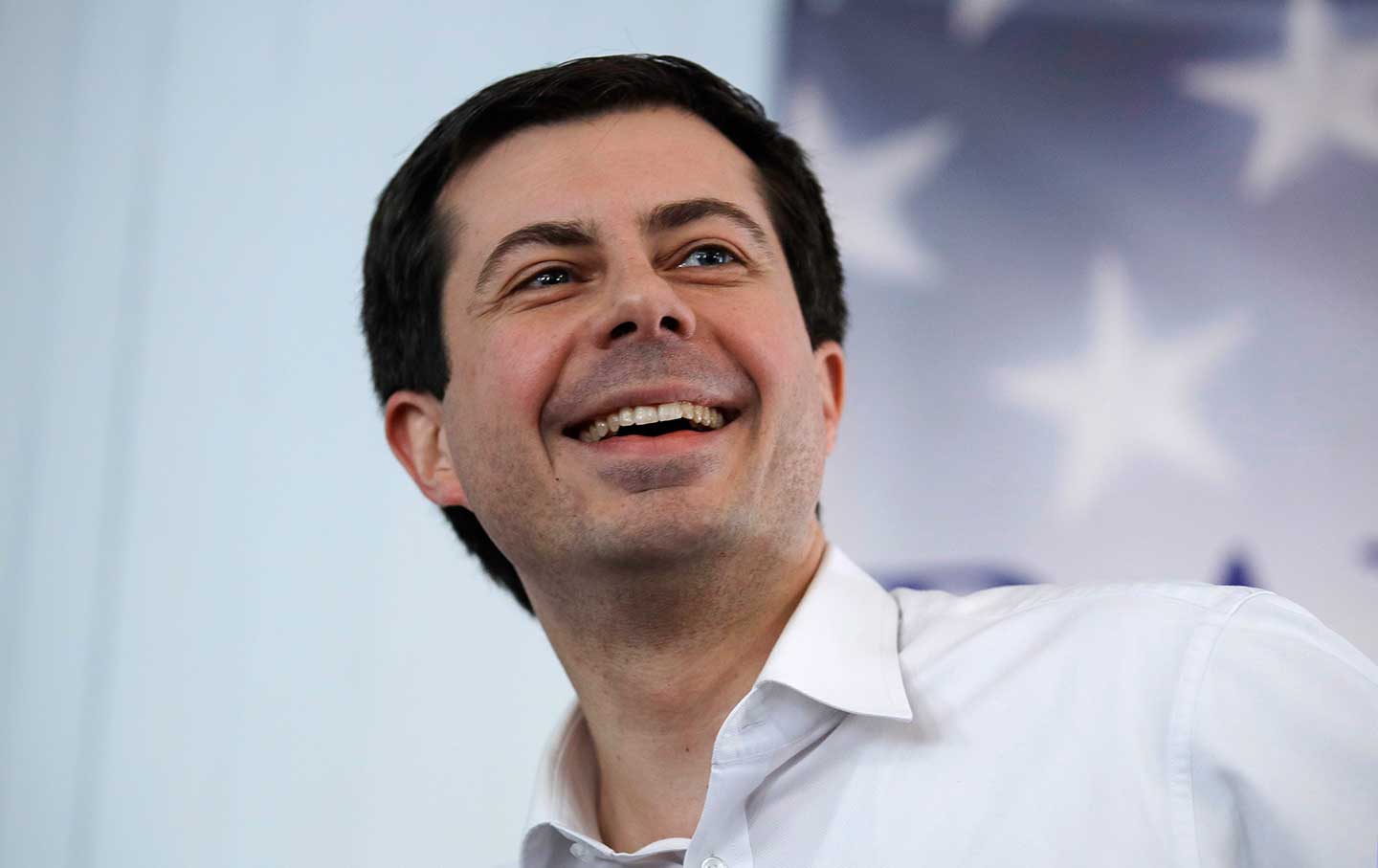

Mayor Pete Buttigieg, of South Bend, Indiana, smiles as he listens to a question during a stop in Raymond, New Hampshire, on February 16, 2019.(AP Photo / Charles Krupa)

We are currently experiencing a crisis that is at once social, economic, environmental, and political. It has a long and deep history; it presents many challenges; and in the best of all possible worlds, we will be working through these challenges for many years to come.

The November 2020 elections are but one moment of this crisis. Even at the political level, the elections are embedded in a much broader set of questions about the political parties, how they will “represent” social groups—classes, ethnic and racial groups, gender identities—and whether or not there will be a significant “realignment.”

At the same time, the outcome of the November elections is enormously important. If Donald Trump is able to win a second term, and remains in the White House for another six years, until 2024, this will represent an enormous setback for public policy and organized politics. Trump would surely veto or obstruct every possible piece of progressive legislation, whatever the partisan balance of power in Congress. He would continue to gut environmental, health, and safety regulations, and oppose federal enforcement of worker rights, civil rights, and voting rights. And he would continue to poison public discourse, foment anger and resentment, and mobilize a right-wing base that will continue to exercise a medium-term political influence out of proportion to its numbers, whatever the long-term demographics of the country.

This would be terrible for the left, and for the constituencies the left claims to represent.

It is foolish to think about electoral politics in conventional “horse race” fashion. Fundamental questions are at stake. And so a very serious debate is unfolding within the Democratic Party and on the broader democratic left. This debate, too, has a long and complex history. But it was brought to the fore by the decision of a political independent and self-avowed democratic socialist, Bernie Sanders, to run in 2016 for the Democratic presidential nomination, and by his extraordinary success in mobilizing voters and building a political base. The debate has been carried forward by Sanders, whose decision to run again was hardly a surprise. And it has been extended by the dramatic growth of Democratic Socialists of America (DSA), and by its success in helping to elect a range of candidates at the local and national levels, including brilliant and outspoken young leaders like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Rashida Tlaib, who have brought a new energy to the Democratic Party.

As a result, there is now a serious discussion underway about “socialism” and who is “a socialist” and who cares.

And make no mistake, this discussion is serious. It is surely being magnified by celebrity culture and social media—which is a real political tool—and by the extraordinary charisma of “AOC.” It is also being magnified by a deliberate right-wing strategy of red-baiting that will only continue to become louder and meaner in the coming months. But it is impossible to discount the fact that self-identified socialist organizations and politicians have become energized, and have promoted ideas—Medicare for All, “Fight for $15,” a Green New Deal—that have resonated, gained traction politically, and generated real political victories.

These socialist efforts draw upon, but are also in tension with, other tendencies within the Democratic Party and on the broad liberal left, tendencies associated with struggles against racism, sexism, genderism, and xenophobia, struggles often described by labels such as “identity politics” or “civil rights” or “human rights.” These socialist efforts are in sharper tension with the more centrist, “neoliberal” tendencies of the Democratic Party establishment.

These tensions are represented in the current Democratic primary field and its almost-20 candidates. And it appears likely that this field will soon officially include that most establishment of establishment figures, former vice president Joe Biden, who has declared himself to be not “a socialist” but “an Obama-Biden Democrat.” Biden is surely the most backward-looking and the most backward of the entire field of candidates. If and when Biden enters the race, he will surely raise the level of tension and indeed acrimony within the party.

The tension and the acrimony is real; it is intellectual, political, and dispositional; and it is both necessary, and healthy, so long as it is enacted within a broader context of agonistic respect: a willingness to be sharply critical without being destructive and hostile, and to receive the sharp criticism of others without being defensive and angry or at least while keeping one’s anger in check. Such political debate, if it is really to engage the pressing issues at stake, cannot be calm, dispassionate, or “moderate”; and it will inevitably be chafing, bruising, and painful. That is agonism. What makes agonism respectful is a willingness to endure some discomfort, to develop thick skin, and to fight back with a sense of proportion and an appreciation that one’s opponents are competitors for leadership of a political party and people with opinions different from your own, and not enemies or demons.

The boundary separating critique from “takedown” is a porous and slippery one. One of the things that distinguishes agonistic respect from insipid appeals to “civility” is a suspicion of efforts to police this boundary, whether the gendarmerie be officially appointed or self-appointed. A politics without “incivilities” is like sex without friction—impossible. At the same time, failure to understand the difference between critique and takedown can be very damaging, for all concerned. In the past week, Jacobin published two pieces that I would describe as takedowns. To be clear, I am talking about two pieces, and not making a blanket claim about Jacobin, much less about socialists or DSA. Indeed, it is precisely such blanket claims that I want to question. But because Jacobin is widely read by socialists and DSA members, and because I regard those groups as important, I regard engaging with these pieces as important.

The chaos and cruelty of the Trump administration reaches new lows each week.

Trump’s catastrophic “Liberation Day” has wreaked havoc on the world economy and set up yet another constitutional crisis at home. Plainclothes officers continue to abduct university students off the streets. So-called “enemy aliens” are flown abroad to a mega prison against the orders of the courts. And Signalgate promises to be the first of many incompetence scandals that expose the brutal violence at the core of the American empire.

At a time when elite universities, powerful law firms, and influential media outlets are capitulating to Trump’s intimidation, The Nation is more determined than ever before to hold the powerful to account.

In just the last month, we’ve published reporting on how Trump outsources his mass deportation agenda to other countries, exposed the administration’s appeal to obscure laws to carry out its repressive agenda, and amplified the voices of brave student activists targeted by universities.

We also continue to tell the stories of those who fight back against Trump and Musk, whether on the streets in growing protest movements, in town halls across the country, or in critical state elections—like Wisconsin’s recent state Supreme Court race—that provide a model for resisting Trumpism and prove that Musk can’t buy our democracy.

This is the journalism that matters in 2025. But we can’t do this without you. As a reader-supported publication, we rely on the support of generous donors. Please, help make our essential independent journalism possible with a donation today.

In solidarity,

The Editors

The Nation

The first article is “Have You Heard? Pete Buttigieg Is Really Smart,” by Nation contributing writer Liza Featherstone. I first learned of this piece when it was posted on Facebook by one of Jacobin’s top editors, with this subtitle: “Liza Featherstone’s hate is pure.” The Facebook caption, like most such posts, was no doubt intended to be attention-getting, and perhaps also to be slightly tongue-in-cheek. And the piece is not “hateful.” But it is dismissive in the extreme, to the point of being sneering. And while it targets Buttigieg, its more important target is all of those who are excited about Buttigieg, as a (Midwestern) politician whose style contrasts so sharply with Trump (who is not an intraparty competitor or an adversary, but an enemy who deserves no respect whatsoever).

Featherstone’s ire is directed primarily to a group first made notorious in the late seventies by Barbara and John Ehrenreich: “the PMC” or the Professional Managerial Class. Some excerpts from Featherstone’s piece clearly convey its substance and tone:

…while the PMC are often eager to be more inclusive about who gets to be “smart”—women, black people—they have tremendous faith in the concept itself. They love rich people whose intelligence has made them prosper: they may cringe at the science-denying Koch Brothers but they went into deep mourning when Steve Jobs died. They devour Malcolm Gladwell’s veneration of the wisdom of genius entrepreneurs over the plodding, clueless masses.…

Smartness culture is social Darwinism for liberals.…

Trump’s proud ignorance and shameless pandering to the nation’s dumbness often seems to gall them more than his inhumane, death-drive policies. This class always seeks a Smart Dude as savior. Obama, of course, represents successful fulfillment of this dream, and they can’t wait to repeat it…

But the obsession with his kind of ostentatious intelligence is deeply unserious and anti-democratic. “Smart” is not going to save us, and fetishizing its most conventional manifestations shores up bourgeois ideology and undermines the genuinely emancipatory politics of collective action. Bernie Sanders, instead of showing off his University of Chicago education, touts the power of the masses: “Not Me, Us.” The cult of the Smart Dude leads us into just the opposite place, which is probably why some liberals like it so much.

I am not a supporter of Buttigieg. But I know many people, including some prominent writers on the left, who do support him. Featherstone’s piece raises some important questions about how Buttigieg’s recent celebrity relates to his actual politics, and how and why our media culture tends to gravitate toward certain personalities, like “Beto” and “Mayor Pete”—but also like “Bernie” and “AOC,” who are no less media-driven personalities than the others. But her piece is not really an attack on Buttigieg, and it ends by conceding that he is good on many issues, and superior to many other candidates and especially to Trump. If Featherstone’s “hate is pure,” it is directed primarily not against Buttigieg but against his supporters, who are “othered” (“They”), parodied, and treated not as interlocutors or serious political opponents within the broad democratic left, but as an arrogant, objectified, class Other—“the PMC.” In recent years this has become a trope on some segments of the left (perhaps the most influential version has been Thomas Frank’s 2016 much-celebrated polemic, Listen Liberal: Whatever Happened to the Party of the People?, which heaped scorn on liberals and especially on Hillary supporters in the run-up to the 2016 election). On this view, supporters of people like Buttigieg are arrogant, privileged liberals who are to be analyzed not in terms of their arguments but as symptoms of neoliberal capitalism, and who are to be treated with suspicion and derision by serious leftists, who know better—and thus support Sanders, who “touts the power of the masses.”

The second takedown is Luke Savage’s “Liberalism’s Hollow Partisans,” a response to Eric Alterman’s provocative but heartfelt Nation column, “The Liberal Case Against Bernie: With a dangerous lunatic in the White House, voting for Sanders is too big a risk.” Alterman’s argument is summed up in its subtitle: With a dangerous lunatic in the White House, voting for Sanders is too big a risk, because Sanders has real political vulnerabilities, and while he might have support among his “base,” he is not the candidate with the best chance of defeating Trump. This is an argument. It probably would have been better served by the title “A Liberal Case Against Bernie” rather than “The.” It might have been less provocative had it been less emphatic; I personally remain agnostic about who can best defeat Trump, and would have preferred “A Liberal Case for Skepticism About Bernie” rather than “Case Against.” But that’s me, not Alterman. He is a left-liberal, and a longtime contributor to The Nation, the most important mass-circulation weekly on the American left, and he is against Sanders for the reasons he offers, and he says so. As he should.

There is an argument to be had here. But Savage does not join the argument. Instead, he savages Alterman, casting aspersions on his motives—something Alterman does not do to Sanders supporters in his piece—and reading him as a spokesperson for something much broader and more insidious: “the guardians of liberal opinion,” intent on articulating “the centrist preferences of the party’s establishment”; a member of “Liberal, Inc.,” who fears Sanders because his “popular message struck a resounding chord within the Democratic base.” Alterman’s fear that in a general election Sanders would be flayed alive by a red-baiting Trump and his red-meat-hungry base is treated as capitulation: “It fast becomes unclear in the ensuing morass of red-baiting where his own criticisms stop and those of the hypothetical Republican attack ads he insists would sink a Sanders presidential campaign begin.” Alterman’s doubts about Sanders’s likely popularity beyond his base are treated as “a deeper rot in the way some liberals have come to think about American politics after decades of dominance by the Right.” And Alterman’s genuine fear of reaction is treated as cowardice in the face of the left’s bravery: “why surrender when you can fight?”

Get unlimited access: $9.50 for six months.

This is too simple a morality tale. Savage is too sure of his own righteousness and of Alterman’s lack of character. He is also too sure about Sanders; in pieces like Savage’s and Featherstone’s, while the Democratic or liberal opponents of Sanders are subjected to withering criticism, Sanders tends to get off scot-free. And while Savage takes Alterman to task for his “liberal” narrowing of the “horizons of possibility,” in fact it is Savage’s critique that rests on such a narrowing horizons: on the one (good) side is Sanders, and on the other (bad) side is Everyone Else.

All Alterman said in his piece is that he is against Sanders now because he has concerns about Sanders and considers the defeat of the lunatic in the White House to be the preeminent imperative of 2020. He said nothing else about whom or what he supports. Perhaps he supports the Green New Deal, or Medicare for All, as a great many of the Democratic candidates not named Sanders now do. Perhaps he supports Elizabeth Warren, who has articulated a powerful left agenda. It doesn’t matter to Savage. By coming out against Sanders now, Alterman has declared himself to be both a “liberal” and an enemy.

What good does this approach serve? The truth is, the concerns that Alterman raises are very real. They warrant substantial attention, especially from serious commentators on the left. For now, two things in particular are worth noting.

The first has to do with the importance of timing: the elevated danger of a Trump second term, which makes Trump, the incumbent occupant of the nastiest bully pulpit in history, more dangerous in 2020 than in 2016; and the diminished appeal of Sanders in 2020, precisely in virtue of his successes in 2016. In 2016 Sanders succeeded in mobilizing millions of young voters, inspiring young socialists, and thrusting “left” ideas to the center of policy debate. Now these political forces are energized, and the issues are at the center of debate, and Sanders the individual simply looms less large. You no longer need to vote for Sanders in order to support Medicare for All or a Green New Deal. It is not irrelevant that AOC has not yet endorsed Sanders or anyone else. And, as the Washington Examiner recently made clear in “Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez says she wasn’t invited to Bernie Sanders’ kickoff rally” in Brooklyn, the reason is not because none of the candidates are sufficiently “socialist” for her: “’I’ve been speaking with him and several other of the 2020 candidates,’ she said. ‘I want to wait until we get a little bit closer’ to endorse a candidate. She said if she endorsed a candidate early in the race for the 2020 Democratic nomination, it would prevent the party from having a conversation about where it stands on important issues, such as income inequality, criminal justice, and the environment.”

This is a serious political judgment offered by a serious political leader. Will she eventually endorse Sanders? Perhaps. But AOC is now a player, and she knows that she is playing a long game, and that the game is not about Sanders, nor is it a simple moral struggle between Good and Bad, Radical and Liberal.

The second point also relates to AOC: She knows that her base is not “the base” of the Democratic Party, and that while there may fertile ground for support throughout the country, there are also enormous obstacles to this support, and much fertile ground for the support of things other than socialism—including some very reactionary things. She also knows that while she entered the House along with one other DSA-member—Rashida Tlaib—and a substantial number of progressive Democrats, most of the “blue wave” involved victories for Democrats who are neither democratic socialists nor Justice Democrats. In 2018, 26 of 79 candidates endorsed by Justice Democrats won primaries, and of those 26, seven—seven—won House seats in November, out of a total of 64 new Democrats in the House. And none of those victories was in a swing district. As Ella Nilsen and Dylan Scott pointed out in Vox, “Most of the new Democrats in the House are more moderate than you think.” To observe this is not to minimize the impact of the Justice Democrat victories or their potential to move the party further to the left. But it is a huge mistake to exaggerate the implications of the 2018 elections or the extent to which “the base” of the party is fertile ground for democratic socialism. The extent of support for a left presidential candidate, even among the Democratic base, is truly an open question, to be determined in practice. It is simply too early to know. The notion that Sanders has the support of “the base” in toto, and that the Democrats who oppose or are running against him are “against the base,” is wishful thinking.

And this brings me back to Buttigieg. He is surely no “leftist.” I personally do not care whether he has read Gramsci or speaks Norwegian or plays the piano. That he speaks with dignity, compassion, and intelligence—these things do matter. Is he the most compelling of candidates? Not to me. Will he even be a viable candidate once his 15 minutes of fame have passed? I am skeptical. Buttigieg is simply one of a number of interesting possibilities in a fairly wide and somewhat open field; and while Sanders is “a front-runner” now, this is no more grounds to count out others than Hillary’s status in 2016 was grounds for dissing Sanders.

Buttigieg is no savior. But given the state of things, it strikes me as foolish for people on the left to dis him or what he represents as a new “outsider” with intelligence and integrity.

There will be red-baiting in the coming months. And there will be Democrats who capitulate to it. In some ways, the despicable recent attacks on Ilhan Omar are a kind of red-baiting by proxy. (There will also be many Democrats who, when pressed, will note that they are not socialists; I do not regard this as a form of red-baiting). But there will be very few Democratic leaders who will discuss this with the seriousness and integrity exhibited by Buttigieg.

When asked recently on ABC about Trump’s red-baiting, he declared: “The President is adopting a tactic that takes us back to the darkest days of the ’50s when you could use the word ‘socialist’ to kill somebody’s career, or to kill an idea, but that trick has been tried so many times that I think it’s losing all meaning. The Affordable Care Act was a conservative idea that Democrats borrowed and they called that ‘socialist.’ So it’s kind of like the boy who cried wolf. It’s lost all power I think, especially for my generation of voters.”

When asked on CNN whether he supported the Green New Deal, he registered unequivocal support for the idea, on the basis of an explanation that could well have been offered by AOC; he then proceeded again to contest Trump’s red-baiting:

I think he [Trump] is clinging to a rhetorical strategy that was very powerful when he was coming of age, fifty years ago. But it’s just a little bit different now …[in the 50’s] the word socialism could be used to end an argument. Today I think a word like that is the beginning of the debate, not the end of the debate. Look, America is a democracy, and it’s a market-based economy. But you can no longer kill off a policy idea by saying that it’s socialist …If someone my age or younger is weighing a policy idea, and somebody comes along and says, ‘you can’t do that, it’s socialist,’ I think our answer is going to be, ‘OK, is it a good idea or is it not?’

Of course this is not an ideological endorsement of “socialism.” But Buttigieg—like most Americans—is not a socialist. What he is, though, is a Democratic mayor of a Midwestern city who publicly and unabashedly declares that he deplores red-baiting and regards the idea of socialism as “the beginning of the debate, not the end of the debate.”

Such a declaration should be welcomed.

We need serious debate. About ideas, policies, and strategies. Those who consider themselves socialists will surely have disagreements with those who consider themselves liberals or progressives or feminists. Such disagreements can bridged through coalition-building around commonalities. But such bridgework is often difficult. For ideological differences involve emotional investments and styles of communicating and ways of being. There will be misstatements and overstatements, fights and hurt feelings and the reopening of old wounds and the creation of new ones. Hopefully there will also be mutual understanding and mutual learning. Otherwise, it is hard to see how we can effectively come together to defeat Trumpism and to advance the values of freedom, justice, and environmental sustainability. And too much is at stake to risk failure.

Jeffrey C. IsaacJeffrey C. Isaac is the James H. Rudy of Political Science at Indiana University Bloomington. He speaks for himself, always; makes no claim to speak for his institution; and indeed wants to make very clear that he is strongly dissents from what his institution’s leadership is now doing.