The Princess Principles for New Orleans

Disney's The Princess and the Frog opened last week. It showcased Disney's first African American princess, prompted significant merchandise sales, and provoked racial and feminist criticism.

As the mother of a 7-year-old daughter, I knew I'd have to see the film. I went to the theater prepared to deconstruct troubling racial images, which Disney has a history of producing, and distorted notions of womanhood, which Disney makes its fortune creating. But I was mostly delighted by the music, characters, and plot. I found neither race nor gender the driving concerns of this animated film.

Melissa Harris-PerryDecember 21, 2009

Disney’s The Princess and the Frog opened last week. It showcased Disney’s first African American princess, prompted significant merchandise sales, and provoked racial and feminist criticism.

As the mother of a 7-year-old daughter, I knew I’d have to see the film. I went to the theater prepared to deconstruct troubling racial images, which Disney has a history of producing, and distorted notions of womanhood, which Disney makes its fortune creating. But I was mostly delighted by the music, characters, and plot. I found neither race nor gender the driving concerns of this animated film.

I read The Princess and the Frog as a forceful and insightful allegory about the restoration of New Orleans.

Like many children’s stories, this one is a morality tale. Parents read to our kids not only to encourage their literacy, but also to impart lessons about our shared cultural and social values: kindness, honesty, courage, thrift, hard work, normative heterosexual relationships that result in lifelong, happy, state-sanctioned marriage. The basics.

This particular morality tale conveys lessons about the city where it is set: New Orleans.

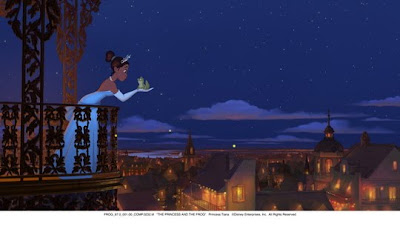

The Princess is Tiana. She grows up in a shotgun house, in a tight-knit, black community, the child of laboring parents. Together they dream of owning a restaurant. Tiana works night and day toward this goal.

Tiana represents the spirit of the people of New Orleans. She lives in the Big Easy, but her life is hard. She has family, community, sharp wit, tremendous talent, and the willingness to labor in grueling conditions. She works and saves her money, but local lenders refuse to honor her bid on a location for her restaurant. (A historic building she hopes to restore.) She is childhood friends with a wealthy family, and while they give her opportunities to work and earn, it never occurs to them to underwrite her dream of owning her own business. Everywhere she turns her dreams are blocked by a system that appears benevolent, but is actually stacked against her.

The Prince is Naveen. He comes to New Orleans seeking good times and jazz music. Naveen is the city’s tourist industry. He lands in New Orleans with a romantic vision of carefree living, good music, and a burden-free existence. The city is excited to welcome him. They view his visit as an honor, but early in the film Naveen is ignorant of the city’s complexity and disrespectful to his hosts.

When Naveen encounters the true New Orleans, in the person of Tiana, he slowly, but assuredly, is converted. New Orleans becomes the place where he wants to settle down, pursue a dream, work hard, and become one with the city whose culture he loves.

Tiana and Naveen’s love story is, in part, the story of many New Orleanians. Even before Katrina, and certainly in the years since the storm, many who began as casual visitors have become committed residents. They, like Naveen, fell in love with the people of New Orleans.

The villain is the sinister Dr. Facilier. Facilier turns Naveen into a frog, and transforms Naveen’s bitter manservant, Lawrence, into a replica of the prince. Facilier’s plan is to dupe sweet, but shallow, Charlotte; to steal all of her wealthy father’s money; to grab power in the city; and turn its residents over to the forces of evil.

Facilier is the New Orleans political establishment. He seeks wealth, power, and influence. He relies on duping naïve and trusting voters (Charlotte) by presenting candidates that are not truly what they seem (Lawrence). He uses sleight-of-hand to try to convince Tiana that he can make her dreams come true without all the hard work (campaign promises).

There is a happy ending. With the help of friends that she meets in the Bayou (rural/urban partnerships) Tiana defeats Facilier, marries her prince, and opens her restaurant.

The lesson of the allegory is clear. The corrupt political establishment that makes false promises, and pursues personal wealth, must be defeated by the hardworking, big-dreaming people of New Orleans. Tiana forms a multiracial coalition with Charlotte, she builds strong ties with her rural neighbors, and she inspires a casual visitor to invest his life and labor in the city. Tiana’s story shows that the talent, drive, and love necessary to rebuild the city are already present in the people of New Orleans.

Drawing on the lessons of her laboring parents and in partnership with her uptown friends, Tiana’s local business is the allegory of a restored New Orleans.

The Princess and the Frog is a love story. It is the story of a city I love. A city that can yet be saved with investment in local talent and coalitions across lines of differences.

*Author’s note: I’ve kissed my own frog prince and I am currently supporting my partner, James Perry, in his mayoral campaign in New Orleans.

Latest from the nation

-

Today 5:30 am

Trump Took Over the Kennedy Center, but Silencing the Arts Will Not Be So EasyAlisa Solomon -

Today 5:30 am

Peace, Not Surrender for UkraineAnatol Lieven -

Today 5:30 am

A New Age for US-Russia Arctic Cooperation?Pavel Devyatkin -

Today 5:30 am

How the American Left Became ConservativeMichael Kazin -

Today 5:00 am

The Workplace Nightmares of “Severance”Jorge Cotte

Melissa Harris-PerryTwitterMelissa Harris-Perry is the Maya Angelou Presidential Chair and Professor in the Department of Politics and International Affairs and the Department of Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at Wake Forest University. She is also the co-host of The Nation’s System Check podcast.