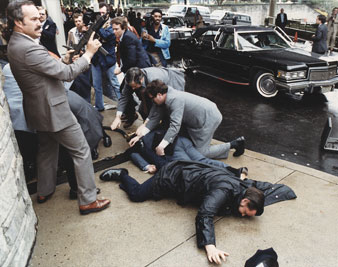

Everett CollectionSeconds after the assassination attempt on President Reagan. James Brady lies (light blue suit) wounded, March 30, 1981.

Everett CollectionSeconds after the assassination attempt on President Reagan. James Brady lies (light blue suit) wounded, March 30, 1981.

John Hinckley may have been the one to pull the trigger, but who’s to blame for his anger?

The attempted assassination of President Ronald Reagan marks the fourteenth assault on the life of an American President or Presidential aspirant (two were directed against President Gerald Ford). Four of them were successful. Three Presidential aspirants, in-cluding Huey Long, were targets. In no other Western nation has the life of the head of state been so perilous. (We are also the only society that has a steady diet of mass murders; assassination attempts are only the tip of the iceberg.)

In this century virtually all of the deeds have been done by a procession of psychopaths, shrewd enough to outwit the Secret Service but mad enough to make a bid for glory by slaying the leader of the tribe. Taken as a whole, they have not been after political power, Brutus-style, but rather have been a breed of alienated grudge-bearers, hatching twisted schemes in lonely hotel rooms, seeking self-transcendence (or immolation) in a blaze of nihilism.

What is it in our society that encourages the sick among us to act out their power fanta-sies with such tragic results? If, instead of sounding the ritual denunciations of the mon-ster in our midst, we could seriously pursue the answer to that question, perhaps we would learn something important about our society, our culture and politics.

Still, for the short run, there are some obvious things to be said. We could not help but notice, for example, that the only public figure who did not perform the ritual handwring-ing was the President himself, who grinned (we can assume) the old seamed grin, how-ever weakly, and told his wife, “Honey, I forgot to duck,” and who begged the surgeons: “Please tell me you’re Republicans.” The President, before his collapse, acted as though he were a featured guest at a Friars Club roast, and one half-expected to read that upon awakening from the anesthesia he had quipped: “Where’s the rest of me?” His resilience, relief at being alive, grace under pressure — whatever it was — provided a brief celebration of the tenacity of life and a reassuring glimpse at an appealing aspect of Ronald Reagan’s character.

Nevertheless, more needs to be done toward reconciling the conflict between the free-wheeling, gregarious style of our politicians and the requirements of security. Accom-modating the demands for an open political style by leaders in a democracy with the need to guarantee the safety of our charismatic pols is the kind of short-run problem that may require a long-run trial-and-error solution. But an immediate and overdue step would be to pass national handgun control legislation — favored, according to the polls, by a majority of the population — which seems to gain a place in the bipartisan agenda only after assassination attempts.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

The most irrelevant comment we heard on the day of the shooting came from a spokesman for an anti-gun control group, who was quoted as saying that since Wash-ington already had strict laws, the incident was proof that gun control doesn’t work. Gun control laws in Washington or New York City or Detroit can never work so long as hand-guns can be purchased at a pawn shop in one state and transported to another. Hand-gun controls won’t solve the problem, but they would begin to reduce the risks. Ironi-cally, the one Federal agency that deals with the interstate arms traffic — the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms — is slated for a severe cutback in the 1982 budget. Op-ponents of gun control, like John Connally, who told a television interviewer that more “discipline” was needed, in the sense of swifter, sterner punishment of all criminals, ig-nore the irrational component in assassinations and, indeed, in most of the murders in this country. An available gun transforms violent emotions into deadly action.

There is another and perhaps more portentous lesson, and it has to do with, to para-phrase another of the President’s quips, “Who’s minding the button?” A brief news item, buried among all the post-assassination-attempt verbiage, reported: “The black brief-case that holds codes needed in the event of a nuclear war remained near President Reagan after he was shot, a White House spokesman said.” The what-ifs such informa-tion conjures up are left to the reader, but they could be continued beyond the operating room itself, to the postoperative hospital bed, where the President was given a narcotic painkiller. When Dr. Dennis O’Leary, the George Washington University Hospital spokesman, was asked if the President would be able to make “a decision of state of some significance,” he replied: “We believe that he would be able to do it.” It’s nice to know what Dr. O’Leary believes (although the Constitution might require a second opin-ion), but that doesn’t make us feel any better about what that black briefcase symbol-izes.

The constitutional problems of “Who’s minding the store?” are tricky in the case of an incapacitated President. We cannot forget how Secretary of State Alexander Haig sud-denly materialized, like an apparition from Nixon’s final days, to announce at a nationally televised news conference that he was in charge — behavior that we may expect the pundits (not to mention the psychiatrists) to elucidate in the days ahead. If Haig could make such an appearance on television, one does not need the help of drugs to imag-ine him appearing in the operating room-or at a hospital bedside — and offering to mind the black briefcase.

Such a scenario may sound like the melodramatic stuff of a television mini-series, but it is standard operating procedure in what E. P. Thompson called in this magazine the nu-clear “Satanic Kingdom.” This episode of the black case demonstrates that the overrid-ing issue is not the mechanics of transferring Presidential power but the power itself — the power to exterminate hundreds of millions of people at the press of a button. This power is too much to be placed in the hands of one vulnerable 70-year-old mortal, how-ever tough; too much indeed to be placed in the black briefcases of leaders of posturing superpowers. The attempt on the life of the President reminds us once more of the fra-gility of life on this planet in the absence of nuclear disarmament.