After Oil

Chevron’s refinery in Richmond, Calif., is a major polluter. Can the activists trying to shut it down convince its 3,000 workers they’re on the same side?

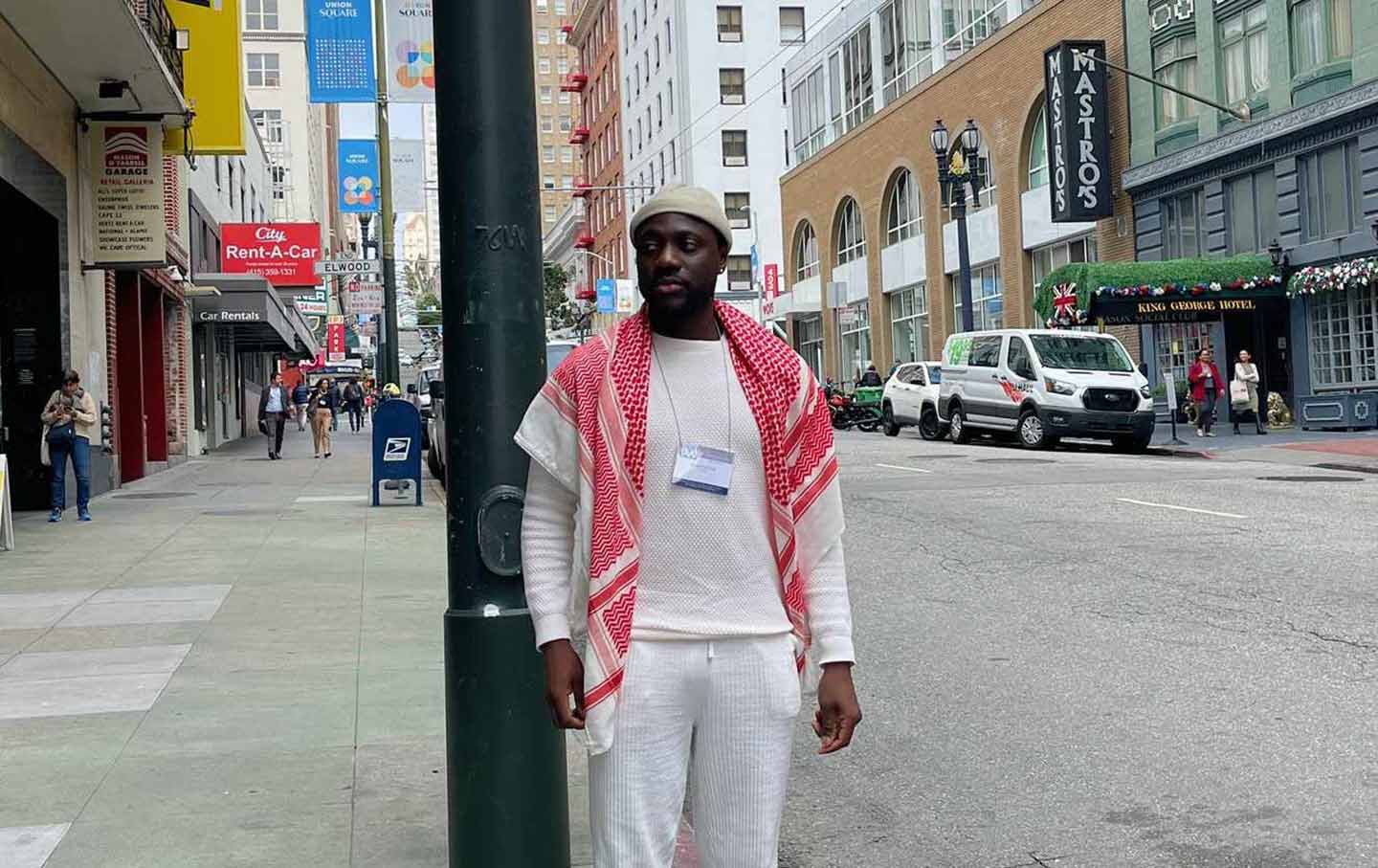

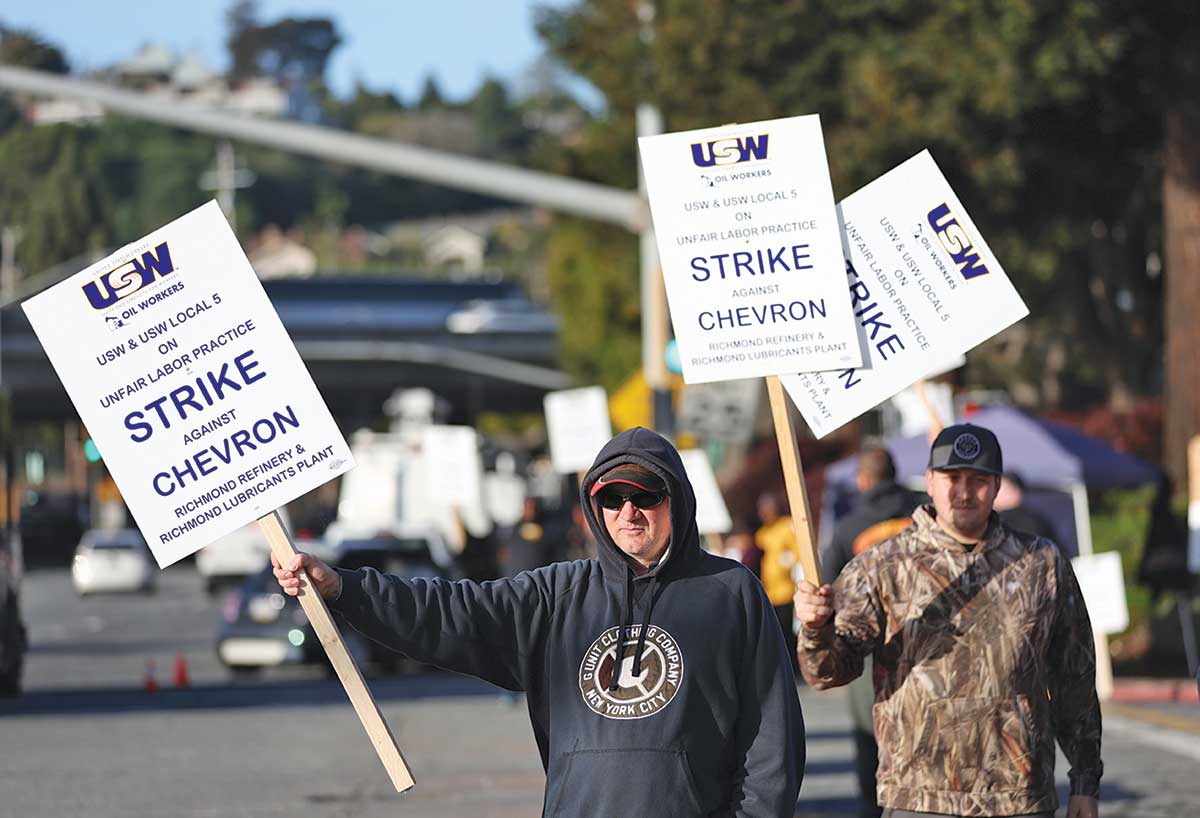

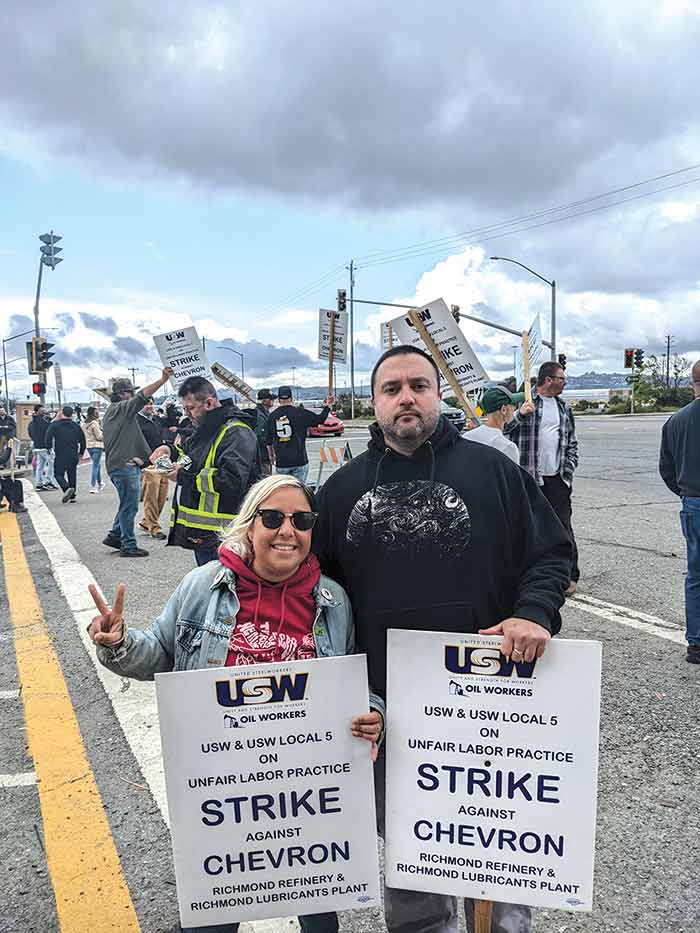

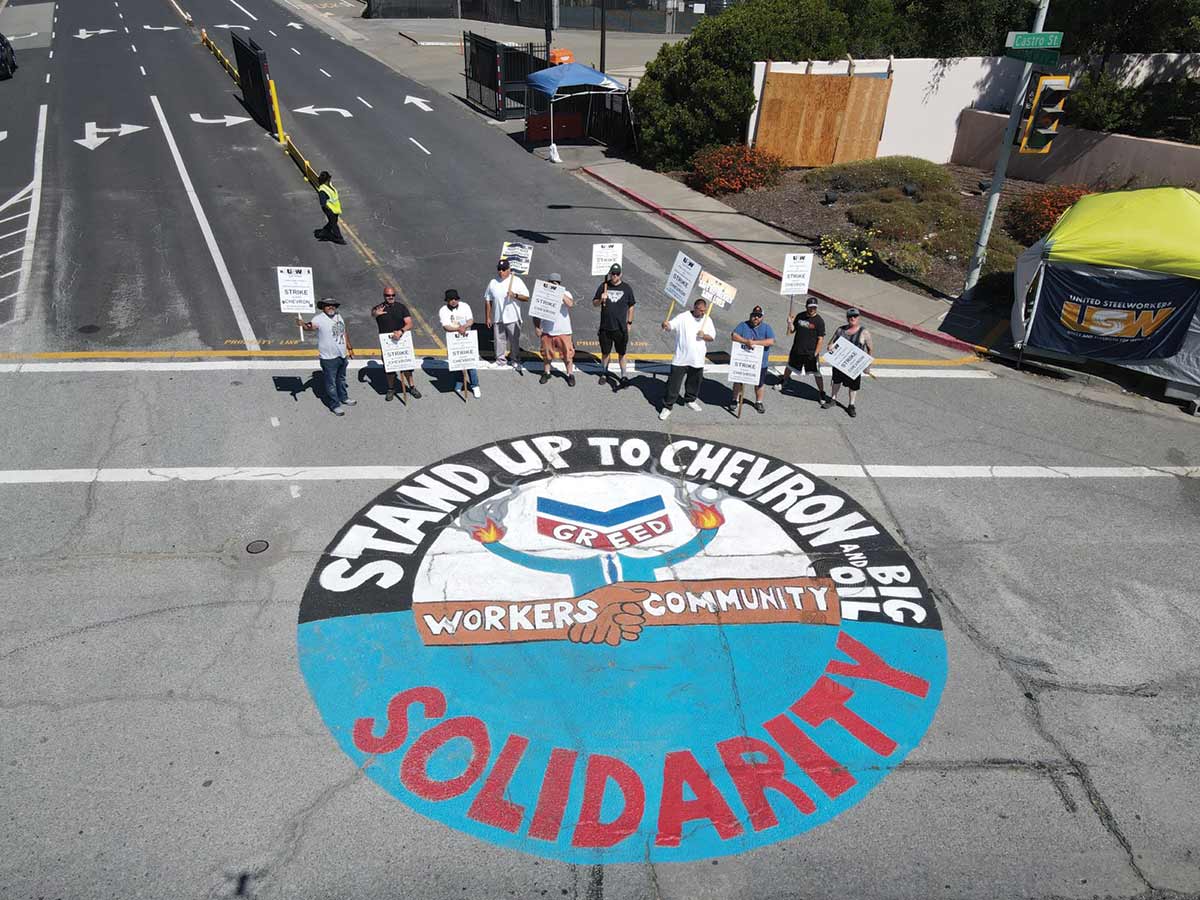

In the spring of 2022, Marisol Cantú found herself in an awkward situation. Several hundred workers were going on strike at the 120-year-old Chevron oil refinery just a few miles from her house in Richmond, Calif., and Cantú, a longtime labor activist, felt she had to show up to support them. “There was no way my spirit was going to allow me to just sit on the sidelines,” she says. But she also knew that the workers might regard her with suspicion. Cantú, an ESL instructor and political activist who grew up in Richmond, had become a vocal opponent of the fossil-fuel industry. On a podcast she’d started, Cantú and her cohosts, two other Bay Area organizers, had called for Richmond to become a fossil-fuel-free community. That couldn’t be achieved without ultimately shutting down the refinery, one of the largest single contributors of greenhouse gas emissions on the West Coast. But that would eliminate the refinery jobs the workers were fighting for.

Cantú was a “union baby,” she says. The granddaughter of a welder and the daughter of two grocery workers—all from Richmond, all steadfast union members—Cantú started volunteering for the United Food and Commercial Workers International Union in the early 2000s, when she was a teenager. In 2019, when she became a professor at Contra Costa College, a community college in nearby San Pablo, she joined the faculty union.

In 2020, Cantú began volunteering for the Richmond Progressive Alliance (RPA)—an anti-corporate grassroots political group that has become a major force in the city’s politics, supporting numerous successful City Council and mayoral candidates over the past 15 years. Progressive politicians here have been surprisingly confrontational toward Chevron. A relatively small number—around 150—of the refinery’s roughly 3,000 workers live in the Richmond area, according to an analysis by the University of California, Berkeley. But the company is the largest taxpayer in Richmond, accounting for about a quarter of the city’s general fund. In addition, Chevron’s philanthropy supports a vast range of services and organizations in Richmond.

However, the refinery is also a health hazard. Petroleum refineries spew pollutants like carbon monoxide, cancer-causing benzene, and particulate matter, a respiratory irritant linked to heart disease, among other serious health problems. In Richmond, refinery pollution mixes with fumes from diesel trucks and emissions from the nearby port. As a result of the poor air quality, the childhood asthma rate here is more than double the national average. Concern and anger over pollution have driven decades of activism against the oil industry in this city. “We have a history of fighting the environmental injustice of Chevron,” then-Mayor Gayle McLaughlin told Democracy Now! in 2013. Her comments came after the city sued Chevron over an explosion at the refinery in August 2012 that sent smoke thousands of feet into the air and led 15,000 people in the region to show up at health clinics, mostly with respiratory complaints.

Even in the face of such health hazards, it is exceedingly rare for local or state political leaders to urge a refinery to pack up and leave—especially when, as in Richmond, it is the area’s most significant industry. In 2019, when a Philadelphia refinery shut down after a horrific explosion sent a truck-size piece of debris flying across the Schuylkill River, some union members campaigned for the facility to reopen—clashing with community groups that rallied for its closure. In the US Virgin Islands, Governor Albert Bryan Jr. has fought to keep a refinery open even after it suffered multiple accidents that rained oil on residents. Meanwhile, officials in Corpus Christi, Tex., have been accommodating a massive expansion of oil and gas projects over the last several years, including refinery expansion—despite the fact that the community has had to contend with high levels of air pollution, oil spills, and a series of refinery fires.

But if the US is ever going to take climate change seriously, communities that depend on the oil industry will need to have difficult conversations about what comes next for the refineries in their midst. In 2020, the California-based environmental justice organization Communities for a Better Environment (CBE) published a detailed analysis by Greg Karras called “Decommissioning California Refineries.” Karras concluded that even with California’s aggressive measures to push electric cars and renewables, the state wouldn’t reach its climate goals unless it significantly cut back on oil processing at refineries. But this has been a thorny issue in California, where hundreds of thousands of jobs still rely on oil and gas. Both the oil and gas sector and some state agencies have argued that refineries could meet some of their emissions-slashing goals through carbon capture and storage, a largely unproven technology that is supposed to stash carbon dioxide underground instead of sending it into the atmosphere. Environmental justice activists oppose measures like this as well as other efforts to repurpose a refinery to produce alternative fuels. They argue that any fuel production at a refinery burdens their communities with an intolerable level of risk, whether from pollution or industrial accidents or both. And these groups do not trust the oil industry to protect health and safety. So CBE (which organizes in Richmond), the RPA, and other allied activist organizations decided they should take action and started an audacious conversation about planning for the closure of the Chevron refinery. Some local activists believed that Richmond itself might have enough legal and political authority to decide when and how this closure would happen—a bold idea, given that state and federal laws often limit a community’s power over industries. If Richmond could pull it off—or even mount a real attempt—the effort would have enormous implications for the entire state and for oil communities all over the country.

For Cantú and other activists, the first step was to discuss the idea with other Richmond residents and see what they thought. In 2021, the RPA launched a community engagement campaign to understand the impact of local fossil-fuel operations on residents. Cantú was hired as a researcher to scope out the community’s views about transitioning away from fossil-fuel-industry dependence. The first part of the project involved a survey of over 400 Richmond residents and about 30 in-depth recorded interviews about Richmond’s refinery—collected at churches, farmers markets, and by knocking on doors. The second part would be a community conversation about the concept of “just transition”—the term of art among activists and scholars for putting an end to fossil-fuel industries while minimizing hardships in communities that rely on them. The RPA decided to present this as a podcast. Despite being “the only millennial [I know] who doesn’t listen to podcasts,” Cantú says, she found herself recording The Listening Project from her home, using makeshift cardboard soundproofing to block sirens and other street noise from the busy intersection outside her door. The podcast often followed a conventional talk show format, with banter on Zoom among the three hosts—Cantú, San Francisco Bay Sierra Club organizer Dani Zacky, and Alfredo Angulo, who was studying political science at UC Berkeley at the time and described himself as “an angry young person who grew up next to a refinery.” But it was also a sociological report turned into storytelling. Community voices from the interviews were threaded together into an almost operatic performance about the community’s frustrations with air pollution.

Cantú’s brother had been in and out of the local hospital for asthma treatment when they were kids, and she often recorded the podcast while holding her brother’s son—nicknamed “Boss Baby” by Zacky and Angulo—on her lap. He sometimes put his young lungs to use in the middle of a recording, wailing and fussing and forcing them to pause. But the toddler also reminded them of the stakes, and the three producers pulled no punches. The fourth episode, for instance, was called “Silent Killer”—referring to fossil fuels. “Fossil fuels are deadly,” says Dr. Amanda Millstein, a Richmond pediatrician, in another episode.

The Listening Project released its first episodes in January 2022, as workers were rallying at the gates of the Chevron refinery. In March, the United Steelworkers Local 5 was in tense negotiations with Chevron when the podcast produced a special episode called “Union Proud.” Cantú facilitated a conversation between Local 5’s vice president, B.K. White, and the Richmond city councilor and RPA member Eduardo Martinez. Cantú introduced herself cheerfully: “This is Marisol—sol, don’t call me ‘Mary’—la prima, la profe [the cousin, the teacher],” and then launched into the interview. The guests, who knew each other—White had longtime friends in the RPA, some of whom had supported USW strikes in other parts of the Bay Area—were united in their frustrations with Chevron. “Chevron’s relationship with its workers is no different than Chevron’s relationship with the community, with government agencies, with oversight agencies. It’s hubris,” White said. White claimed that the company’s arrogance had led it to ignore safety in the refinery, which worsened its environmental impacts and put workers at risk. Martinez spoke about what he believed the future held for the industry. “I’ve been trying to get [Chevron] to start a conversation around a just transition,” he said. “We know that eventually, oil will fade out and renewables will come in, and the best time to have a conversation about that transition is now. Later is not going to cut it.” But it was clear that all three voices were treading a careful path through thorny issues—with Martinez speaking outright about closing the refinery and White insisting that the community and the workers should be allies in fighting for plant safety.

Two weeks after the episode aired, the union announced a strike in Richmond, the first in over four decades. It would ultimately last more than two months and consume the attention of the Richmond community. And it would force the awkward conversation about the future of refining in Richmond into the spotlight. What will happen to this refinery town when the green economy arrives? And does anyone in the community get to decide how it will all play out?

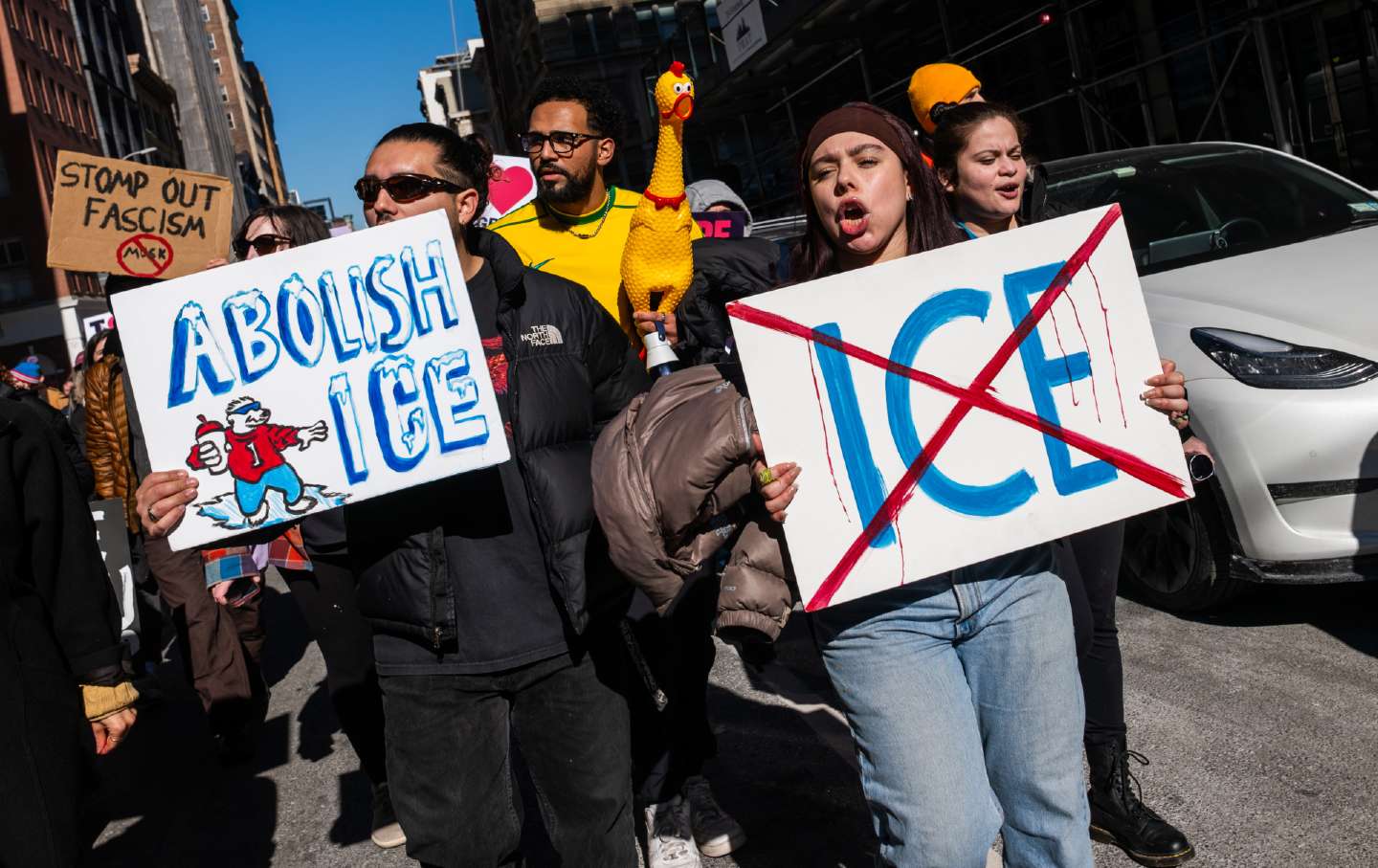

In recent years, the phrase “just transition” has gotten a lot of use, but its meaning is sometimes muddled. It’s partly a political term, appearing, for instance, in the United Nations’ Paris Agreement on climate; all 196 parties to the treaty pledged to take into account “the imperatives of a just transition.” The Green New Deal resolution introduced in the US House of Representatives by Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez in 2019 also calls for a “just transition for all communities and workers.” The phrase has also been used to describe any gesture toward green energy—and it has been invoked enthusiastically by everyone from the World Bank to Greenpeace to the oil giants ExxonMobil, BP, and Shell (though an independent analysis of major oil companies in the journal PLOS One found that their just-transition endeavors were “insignificant and opaque”—as in all talk, very little action).

The original concept of a “just transition” came not from environmentalists or industry but from the labor movement. In 1993, writing for the EcoSocialist Review, labor leader Tony Mazzocchi—formerly the secretary-treasurer of the Oil, Chemical and Atomic Workers Union, which later merged into the United Steelworkers (USW)—published a prescient essay about the decline of US manufacturing and the tension between the need for jobs and the aims of the environmental movement. The federal Superfund program, which provides money for cleaning up toxic pollution at defunct industrial sites, did nothing to help the former workers of those plants, he wrote; instead, they were thrown “onto the economic scrap heap, blacklisted because of their toxic exposures on the job and impoverished by a lack of comparable employment opportunities.” Mazzocchi called for nationwide investments to help such workers with job transitions. “The only way out of the ‘jobs versus environment’ dilemma is to make provisions for the workers who lose their jobs in the wake of the country’s drastically needed environmental clean-up projects, or who are displaced by economic restructuring, military cutbacks or shifts of manufacturing facilities overseas.”

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Some sought to heed Mazzocchi’s call. In 1990, Senator Robert Byrd tried to add a provision to the Clean Air Act that would have provided financial assistance to coal miners who lost their jobs as the result of curbing that industry’s emissions. But President George H.W. Bush promised to veto the provision, and the Senate rejected it in favor of a much larger package of clean-air amendments.

Today, the most meaningful federal efforts to engineer a just transition are shoehorned into pieces of the 2021 Bipartisan Infrastructure Deal, which includes money for clean-energy projects and mine reclamation, and the Inflation Reduction Act, passed last year—fundamentally a budget appropriations bill with an unprecedented level of funding for efforts to cut carbon across the economy. The IRA offers extra tax credits for private companies that build new clean-energy projects in “energy communities”—places especially dependent on coal, oil, and gas production, transport, or processing. It also makes grants available to “disadvantaged communities”—including Richmond—for pollution-fighting and climate-resilience projects. On top of all that, the Biden administration has mandated, via executive order, spending 40 percent of federal climate investments on such communities.

These policies may help send new economic development and job opportunities into at least some of the places where fossil-fuel industries are fading. But they don’t deal directly with the long and cumbersome process of closing down the industries themselves. “We need to think bigger. We really need to be thinking comprehensively about what are the specific challenges of these communities,” says Devashree Saha, the director of the US Clean Energy Economy Program at the World Resources Institute. “It is not just the immediate impact on employment…. It is also the long-term impact of losing tax revenues. Who cleans up these contaminated sites? You need multipronged approaches to solve these challenges.”

Meanwhile, unions and political leaders don’t always agree on what a just transition should look like. In 2021, a group of California unions commissioned researchers at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, to develop a just-transition plan that would embrace the state’s shift to renewables and green jobs and help approximately 112,000 fossil-fuel workers with retraining, lost wages, and healthcare. Several unions have since endorsed it, but in 2022, when California Assemblymember Al Muratsuchi introduced a bill based on the plan, it quickly died in committee, partly because labor wasn’t united behind it. Even the USW emphasizes that it doesn’t expect to push its own industry out of the fossil-fuel business—it advocates for “a future with continued demand for petroleum products.”

On the ground in places like Richmond, “just transition” can sound confusing or divisive. “For some people, the transition means shutting down all refineries and stuff, but there’s nothing else after that,” says Frank Ungo, a refinery worker with USW Local 5 who was part of the 2022 strike. He also fears that he and his fellow oil workers might not have a shot at the new green jobs, even if those positions are unionized. Nor are activists always clear about how a just transition will work. “A lot of our community members don’t resonate necessarily with the jargon of a ‘just transition,’” Cantú notes. She found her neighbors responded better when she talked about creating a fossil-fuel-free Richmond.

But when Cantú started showing up on the Chevron picket line in March 2022, she sensed that it wasn’t the place to launch a discussion about the end of oil. She watched some of her progressive friends introduce themselves as environmentalists. One worker immediately walked away. She heard another say, “Fuck you.” A union leader advised her privately, “If you try to say ‘Shut down this refinery,’ you will start a war.” So Cantú settled on a different goal: “I am trying to build relationships and trust with them, so they do not walk away when it is time for really hard and rough conversations.” She started instead with a more immediate question: What did the strikers need? The answers were simple: food and warmth.

A strike is a major production. Hundreds of people take shifts sitting out in the elements, day after day—a sort of rotating encampment that sometimes feels like a street festival or sporting event and sometimes like a heated confrontation. Cantú and her allies—from a range of local organizations, such as the Asian Pacific Environmental Network (environmental justice activists) and Urban Tilth (urban farmers)—joined forces to help feed the strikers. For instance, the activists set up sandwich lines and made hundreds of sandwiches to bring to the strike. They also rounded up fresh fruits and vegetables, oatmeal, bagels, pupusas, and soups. Cantú picked up pan dulce (Mexican pastries) one night for the workers. She asked a friend who worked at a farm stand to save boxes of fruit to carry to the line. City leaders also showed up, including City Council members Gayle McLaughlin and Eduardo Martinez. One RPA organizer helped run media outreach for the strike.

On some days, the strike was low-key. At other times, the union rallied massive crowds to the gates. In those moments, “it was electric,” Cantú says. “It was also extremely scary, because…you saw workers whose livelihoods have been stopped because they felt the need to fight for a fair and just contract.”

Cantú also noticed that the workers were uneasy about what was happening at the refinery in their absence. Chevron had bussed in temporary workers to operate the refinery (known to the protesters by an old labor slur, “scabs”). But the longtime refinery operators worried that the newcomers wouldn’t understand some of the plant’s functions. “I worked in their refinery for 29 years. You couldn’t drop me in another refinery and have me run it proficiently, because there’s so many esoteric parts of these plants,” says White, then the USW Local 5 vice president. As the strike proceeded, the workers watched the refinery flare—flame and clouds of smoke surging from the stacks. A flare is an industrial process that burns off excess gases and relieves pressure during operations—and can release pollutants linked to cancer, respiratory problems, asthma, and heart disease. Flares can also be an indication that something has malfunctioned. (For instance, the previous October, a leaking roof and the loss of a backup power supply forced the Chevron refinery to flare for three days.) According to White, the flares during the strike looked especially problematic—recurring sooty, black plumes rolling into the sky. Cantú learned from the workers that these were signs of danger—and they were worried about another industrial accident that would put all of Richmond at risk. “They had such a sense to protect,” she recalls later. “I don’t even get that from police officers.” Cantú searched for some way to help: “They’re ready to move into action like first responders, and I’m just sitting here, duck out of water, like ‘What am I to do?’” She began organizing a grassroots reporting system—photographs, texts, drone images, documentation of the worrisome symptoms of mechanical trouble visible at the refinery—to be sent to regulators. She also set up an in-person meeting between union representatives and six regional air district regulators.

Cantú says their complaints are still being investigated, and Chevron disputes any assertions that there were safety problems during the strike. (“We continued to safely produce much-needed gasoline, diesel and jet fuel while the refinery was staffed by management, non-striking employees and workers from our other operations,” a company spokesperson wrote by e-mail.) But the process was important for other reasons. For starters, it strengthened the relationship between community activists and the strikers. Cantú and some of the union representatives became close. “There was a common enemy, if you will,” Cantú says, “and that was Chevron management.” And it became more obvious that the union and the activists had common goals—especially safety and long-term economic security—even if they didn’t always agree on how to reach them. “We’re always fighting with the company regarding safety inside the plants,” Frank Ungo says. “We feel that if an employee is safe inside the plant, so is the community outside of it.”

However, the activists and union members also had diverging ideas about the future. On their podcast, Cantú, Angulo, and Zacky reflected on some of the results of their community survey. Only 32 percent of the over 400 Richmond residents they asked thought the refinery was beneficial to the community. Two-thirds agreed that it would be a positive development if Chevron left the city altogether. But Chevron workers were still fighting for their jobs. In May 2022, the workers reached an agreement with the corporation—but with fewer gains on healthcare and wages than union representatives say they had hoped for.

On the anniversary of the 2012 refinery fire, less than three months after the strike ended, hundreds of Richmond residents held demonstrations of their own at multiple points in the city on foot, on bicycles, and even by kayak near a spot in the San Francisco Bay where a ruptured Chevron pipeline had spilled 600 gallons of diesel the year before. The demonstration was festive, but its message was clear: “Help us make sure the world knows that Richmond’s fenceline communities believe that 120 years is enough” read an event flyer, using the term for anyone living near a fossil-fuel facility. Doria Robinson, who leads Urban Tilth, had decided to run for the City Council. (She won last November.) Robinson admitted that the community wasn’t sure whether its local government had the authority to force the refinery’s closure. “We’re unsure of how much power we can have, but we’re definitely willing to see,” she said. City leaders have embraced other aggressive measures to wind down fossil fuels. In 2020, Richmond passed an ordinance to phase out coal storage and export facilities. In 2021, following the examples of Berkeley, Seattle, San Francisco, and a number of other local governments, the Richmond City Council banned natural gas hookups in new construction—a month before New York City did the same. Richmond also passed a “Green-Blue New Deal” ordinance with the goal of decarbonizing the city’s economy by 2040. But the refinery is still untouched.

In an era of unstable oil demand, market forces alone have already shut down some US refineries. In 2020, two refineries in the Bay Area—in Martinez and Rodeo—announced they would close their oil operations. Both are trying to convert to biofuels, a controversial product that some analyses say may not be less polluting than oil. The Martinez refinery laid off hundreds of workers and is currently idle, and the Rodeo plant would also have a reduced workforce for biofuels refining. So far, there has been no just transition. “The people that were displaced, my brothers and sisters that were displaced…have struggled to find jobs that have a similar pay structure, benefits, and to use their knowledge and skills,” Ungo says bitterly. “In my opinion, nobody—not the state, not the environmental groups—care about them.”

A moment like this could easily arrive in Richmond. More than a decade ago, Chevron suggested publicly that it might also close the Richmond facility in a time of high crude prices and low profit margins. But when asked recently about the Richmond activists’ campaigns for a just transition, a Chevron spokesperson said that the company has no intention of shuttering the facility, insisting that “the world remains hungry for transportation fuels” and that “Chevron is excited about Richmond’s future.” The company also points to a range of pilot projects it’s undertaking to produce hydrogen, including one in Richmond that will generate hydrogen from methane that is off-gassing from a landfill.

But some analyses show that hydrogen production can be more carbon-intensive than even conventional fossil-fuel power, particularly when that hydrogen is produced with natural gas—which is true of 95 percent of US-made hydrogen. Moreover, it’s not clear that transitioning to hydrogen or alternative fuels can sustain old fossil-fuel industrial sites—even a rosy report produced with industry consultation predicted that hydrogen could make up between 1 and 14 percent of US energy demand by 2050. Oil currently represents 36 percent of American energy use. Some community members and leaders in Richmond take a dim view of Chevron’s hydrogen plans. “It’s a lot of greenwashing that we’re very suspicious of,” McLaughlin says.

The state of California has only begun to plan what happens to its refineries, and many unanswered questions remain about the fate of the facilities, their workers, and the communities that live around them. Last year, the California Air Resources Board released a new scoping plan for the state’s signature climate change law that assumes a “phasedown” but not a complete “phaseout” of oil and gas operations by 2045—relying on measures like carbon capture and storage to zero out what remains. Earlier this year, Governor Gavin Newsom signed into law an effort to prevent oil companies from unreasonably spiking the price of gas that also requires the state to put together a “Transportation Fuels Transition Plan.” But according to written comments from the Asian Pacific Environmental Network, that plan “falls far short of meeting the needs for things like cleanup and repurposing of refinery lands, gap funding for public services, and assistance for displaced fossil fuel workers.” In the 2022–23 budget cycle, Newsom allocated $40 million to a fund to support displaced oil and gas workers and another $20 million in Los Angeles and Kern counties to train such workers to plug out-of-commission oil wells—so far just a one-time investment. The state didn’t renew its support for the program in its most recent budget.

In last November’s elections, progressives in Richmond took a wide majority—five of seven seats—on the City Council, and Eduardo Martinez won the city’s mayoral race. Since then, city leaders have become even more direct about pushing for an end to refining activities. “We want to decommission Chevron,” McLaughlin says straightforwardly, and “we want good clean jobs for our residents.” Community leaders and activists are also researching what legal tools Richmond could deploy, says Mayor Martinez, to push the company to set aside money for land cleanup. (If the Chevron refinery shuts down, there will be nearly 3,000 acres of land to contend with—much of which may be highly contaminated.) Such a requirement could begin only after 2025, after a legal settlement over taxes between Chevron and the city runs its course.

Last year, Los Angeles, which sits on an active oil field, enacted a plan to shut down all drilling within city limits by no later than 2042. To do this, it will rely on “police powers, which are basically powers that local governments have—authority over the health and safety of their residents,” says Maya Golden-Krasner, an attorney at the Center for Biological Diversity. The LA drilling ban also needs to survive legal challenges from multiple oil companies over a range of issues, including whether it constitutes an unconstitutional “taking”—the seizure of private property without compensation. Still, Richmond could try the same. But there are many more jobs—especially union jobs—at stake in refineries than in the operation of oil wells. If Richmond is going to undertake a just transition at a local level, it will need to find a common vision that speaks to both the hopes of residents and the needs of the workers whose livelihoods are at stake.

Cantú, who is now a member of the RPA steering committee, is still leading the charge on this. Recently, she encouraged Frank Ungo to apply to participate on an advisory committee on air pollution, and she’s continued to organize a grassroots effort with Chevron workers and local residents to document instances of flaring and air-quality concerns. The podcast has ended, but the project gave the community a trove of data about what residents want. “There were concerns from workers and community members [about] the toxic land,” she says. “Also, looking at reparations, some type of right to have healthcare for long-term chronic health burdens that have been placed on the community.” Cantú feels that those ideas are the seeds of new local policies.

B.K. White—who was fired by Chevron, a move he claims was retaliation for his leadership in the strike—became Mayor Martinez’s policy director in early 2023. White still does not hold the same views as some of the more aggressively anti-oil progressives in the city. “We believe in the regulation of industry and not the abolition of the industry,” White said recently—with “we” referring to the labor movement. But he’s not sentimental about the oil industry. Just transition is “about what happens to your workers when you close the gates,” he said. “We don’t mourn for the deaths of the industries, you know. We’re overwhelmed with sympathy and concern for the communities and the people that are left behind by the vacuum that’s created in these societies that are heavily dependent on singular, dying industries.” Oil, White admits, is dying, and Richmond can’t depend on it any longer.

Editor’s Note: An earlier version of this article said that California slashed funds to support and retrain displaced oil and gas workers in its most recent budget. In fact, new funding was not included in the most recent budget; however, the original funds can be spent until 2025.