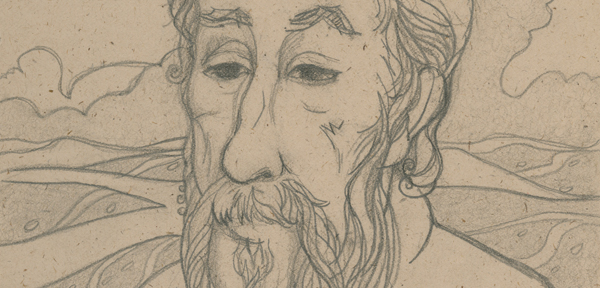

"Literary Lion in Winter," by Dame Henriques

Shortly after I heard from my mother that our close friend, the novelist Sol Yurick, had died at age 87, the obits began appearing. I was glad that Sol, the first serious writer I knew and a strong influence on me as a teenager, was getting recognition. But I was also chagrined that the obits almost exclusively focused on The Warriors, a work he wrote in 1965 about warring New York gangs based loosely on Xenophon’s Anabasis that went on to became a movie and cult hit. Sure, it was a fast read and his most popular work, filled with his requisite cast of rogues, misanthropes, disaffected youth and innocents but the gang bang work hardly defined Sol, who liked to remind people that he wrote it in all of three weeks. His more substantive novels that made a stir in the ‘60s and ‘70s—The Bag, Fertig, and his short story collection, Someone Just Like You—and his later works such as An Island Death, Richard A. and extended nonfiction essay, Metatron, were hardly considered though they defined Sol far more than the Warriors.

Taking Someone Just Like You down from my bookshelf after years of neglect, I’m impressed by the writing, though it’s hard for me to separate the work from the man. I can’t really judge his literary merit against the backdrop of the ‘60s. I’ll leave that to the Ph.Ds. I can just appreciate the words, like the opening of the short story, “The Annealing”:

She lived from day to day and didn’t much care which day it was. If she laughed once or twice, laughed big that day, she had it made. If she cried more than she laughed, she knew it wasn’t her day. Sometimes it wasn’t her day, not really, for weeks on end. Sometimes, with that liquor sloshing around in her, it was her day, her night, her everytime.

This is the sordid tale of a woman with five kids caught up in the welfare bureaucracy who becomes the victim of a state-employed psychiatrist. It’s related to his longer work, The Bag, which he felt was his best novel, and from the first words displays a richness that came from close observation. The only contemporary I can think of that’s mining a similar vein, with a dogged eye and compassion for the powerless, is the non-fiction writer Katherine Boo. Sol, though, was a trenchant critic of society, of capitalism, and of the ideology that underpinned it, and he often let his rage show. As the novelist Brian Morton wrote in The Nation back in 1983: “Yurick has always been fascinated by the myths that mask relations of power and prevent a dominated population from understanding its condition. His novels are filled with deluded true believers, passionate adherents of ideologies that leave them incapable of seeing what’s in front of their eyes.”

Fertig, which caught the eye of actor Alec Baldwin, was also made into a movie, “The Confession.” The book tells the story of a father whose son died because of medical neglect in the ER. Driven to despair and then rage, Fertig turns on the doctors and administrators to eke out his revenge. But the movie twisted the story, which was really too bad, because Sol was three or four decades ahead with this tale of an out-of-control medical system that could cause a person to snap.

If Sol targeted malevolent institutions, he also had no patience for poseurs, especially the literati, who traded on their name and access. In a scathing February 7, 1966 Nation review of Truman Capote’s celebrated novel In Cold Blood, he skewered the myth that Capote had created a new “art form” with the non-fiction novel. “Like the newspaper approach,” he wrote, “the poverty of Capote’s ‘new’ art form is appalling, the shallowness stupefying…. A work of art should, presumably, continue to shape our easy acceptance of the world, make us see in new ways, create new metaphors with which to view the world; new art should go beyond engineered reality.”

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

By the 1980s, he had largely left fiction writing behind. His interests focused on history, metaphysics, cybernetics, genetics, mythology and the information economy, bringing this into a long theoretical work, Burning, that took him a decade to write and ran to more than 1,000 pages, as I recall. I heard a lot about it while I was away at college, but never read it. “Parts of it were brilliant,” said Ron Hunnings, a close friend of Sol’s (and my brother-in-law) who often met him in Village cafes. Sol spun off a portion into Metatron, but the bulk of it never was published, and I think that took a toll on his psyche. Part of this may have been due to the wide scope and density of his thinking, which could not be compartmentalized. As his friend, Robert Shapiro, a computer scientist, told me, “Sol had a totally different take on things. Whether it was Marxism, Darwinism, Greek mythology, or Jewish mysticism, he was always interconnecting things at so many different levels.”

This had its costs. Morton says in his review of Metatron: “At times all this makes-for forbidding reading. At times, too, Yurick ascends into regions of abstraction where I can’t follow … I lose him in the mists.” He wasn’t alone. We all had a hard time, because Sol’s writing—and thinking—was at times akin to free-jazz improvisation, the Ornette Coleman of the non-fiction essay. When it worked, it really worked. But sometimes you just had to give the musician time to find his way.

Because of his wide swath of interests, it would be inaccurate to peg him as a Marxist or anything else—sitting at his oak kitchen table on Garfield Place in Brooklyn’s Park Slope, the ever-present pot of coffee on the stove, the three cats lounging on the parquet floor, the hand-rolled cigarette-making machine nearby, he railed against the powers that be, whether political, bureaucratic, literary, military-industrial, scientific or misguided leftist. In the past few years, he reserved a few choice digs for the pragmatic Obama. In this respect, he was closer to Groucho than Karl Marx: he wouldn’t belong to any club that would have him as a member (PEN was the exception). I even recall one time, when The Nation failed to cut him a check in a timely manner, he exclaimed—“the gonifs!” To which his wife Adrienne would inevitably say, “Oh, Sol, stop it.” He would just smirk.

But the lack of money was a perennial problem and I saw it close hand, for years, especially as Park Slope gentrified and rents got out of reach. The family actually moved into my mother’s house on the Flatbush side of the Prospect Park, when she left for Japan on a Fulbright fellowship. From there, they moved again to a brownstone on Lincoln Road, helped out by close friends who bought the house and rented it to them. Sol’s living example of the writing life was a cautionary tale, so when I chose to do “something with writing” post-grad school, I sought a job on a reporting beat that I knew would always attract a pay check: business. Plus, I had an inherent interest in economic arcana (maybe that was influenced by Sol, too). When I later turned to food and agriculture, Sol had a lot to say, though it was often on the Biblical and historical echoes to contemporary agro-ecological concerns.

During this prolonged period of infrequently published work, The Warriors kept popping up, with the attendant out-of-the-blue interview requests, but despite the delight he got in its cult status, it did not mean a lot more to him. He often referred to it as a “pot boiler,” and sell it did. The book was amazing, really. After the movie brought the novel back to light in 1979, it was reissued time and again; then there were the video games based on it, as well as action figures, memorabilia, comic book, fan web site and still another planned remake of the movie. Over this past Thanksgiving, Sol mentioned that a British production company had optioned it for a musical. The Warriors on stage with singers and dancers! He would have liked to make the London premier, but it was probably all well and good: it would just be another opportunity to rail at a remake. Aside from the Warrior royalties, which trickled in for four decades, Adrienne supported them and then family money finally came their way. After years of just making ends meet, they no longer had to worry about the bills.

I sensed that he mellowed in his final years. Was it his close family and friends, an especially animated grandson? He still raged at the machine, but the deep bitterness, the sting, seemed gone. Mostly I remember him enjoying his bagels and lox on Sunday morning, or the lucious Grand Marnier mousse his daughter Susanna made without fail for Thanksgiving dinner. He ate three or four of those rich desserts at the last gathering. “And why not?” he’d say. Why not, indeed. He had his way until the end. He still spit out the outrageous statement, never one to shirk from intellectual shock value. And while he talked about his writing, it had been years since he had published anything. I sensed that he had lost interest in the whole process of editors and publishing companies, though he still shared his work with friends.

Last year, he sent me an unfinished piece, “A Meditation on the Theories of Accounting,” which revisited his critique of In Cold Blood, putting the murder story of the farm family in the much wider context of, to grossly simplify, industrial agriculture. The essay, like much of his work, doubled back on itself and has digression upon digression. I recognize the ideas, and the approach: he’s trying to change the context of In Cold Blood to illuminate it; to see how by using a wider lens he can reinterpret “fact.”

Perhaps that’s what I’m trying to do too, having read the obits. He had thought a lot about storytelling, so wouldn’t be surprised. In 2011, he wrote this in an unpublished piece:

Zig zag, that’s how memory-retrieval works. Significant events get distorted when looked at through time’s and ideologies’ truth-bending lenses, like light traveling through curved space. Indeed nothing is straight in our universe, other than the idealistic paths of logic and mathematics. And while traumatic events become etched in the very synaptic spaces, events of no significance also remain. And dreams – eruptions from the mysterious realm of the unconscious which, as Freud would have it, knows everything – become mixed with scenes from books read, films, paintings, etc., compounded into a soup that includes excerpts from history, as well as religious and secular mythologies. Add to this that no story – technology notwithstanding – can be told again in exactly the same way. For each time we return to a memorable moment, be it individual or collective, or a mix, we are in a different context and this alters the story.

One of the last photos I have of him is sitting on the couch with a three-year-old niece, who had decided that Sol was now her best friend. They made an unlikely pair. Sol, with his deep, dark eye sockets and serious mien. Elina, with her kind, innocent smile. Before going to bed that day, Elina asked her parents to make sure they invited Sol to her birthday party. We all got a chuckle out of that because she didn’t mention anyone else. Though he promised to come, Sol died too soon. Maybe she saw something in him so many others missed.