According to a new analysis of tax and census data, Mitt Romney’s economic plan is heavily tilted towards big cities, but tough on the rural areas that comprise the GOP’s base. Barack Obama’s economic proposals lean the other way, offering little to wealthy urbanites, while delivering broad tax savings to the middle- and lower-class Americans spread across the South and Midwest.

The findings, released Thursday by a start-up called Politify, present a novel way to view the diverging economic promises in this recession election. In a race dominated by the rhetoric of deficits and the 99 percent, Politify says it offers unassailable data and objective answers for voters wondering how the candidates’ plans will affect their wallet, their neighborhood, or the whole country.

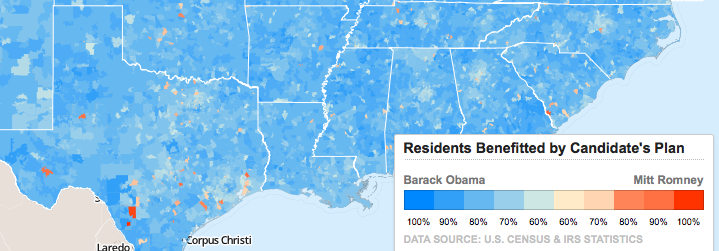

The most dramatic image—which organizers believe will spread quickly online—provides a geographic model of how the candidates’ plans for taxes and benefits will impact individual households. All the data is from the IRS and a US census survey. Nikita Bier, Politify’s founder, says this is the most granular model of campaign policy impact ever created. After he first ran the numbers, Bier recalls that he was “shocked” to see just how severely the results favored Obama’s plan:

The map clearly shows that Obama’s proposals benefit a larger portion of the electorate,  but the visual effect is exaggerated, since the map is not weighted for population density.

but the visual effect is exaggerated, since the map is not weighted for population density.

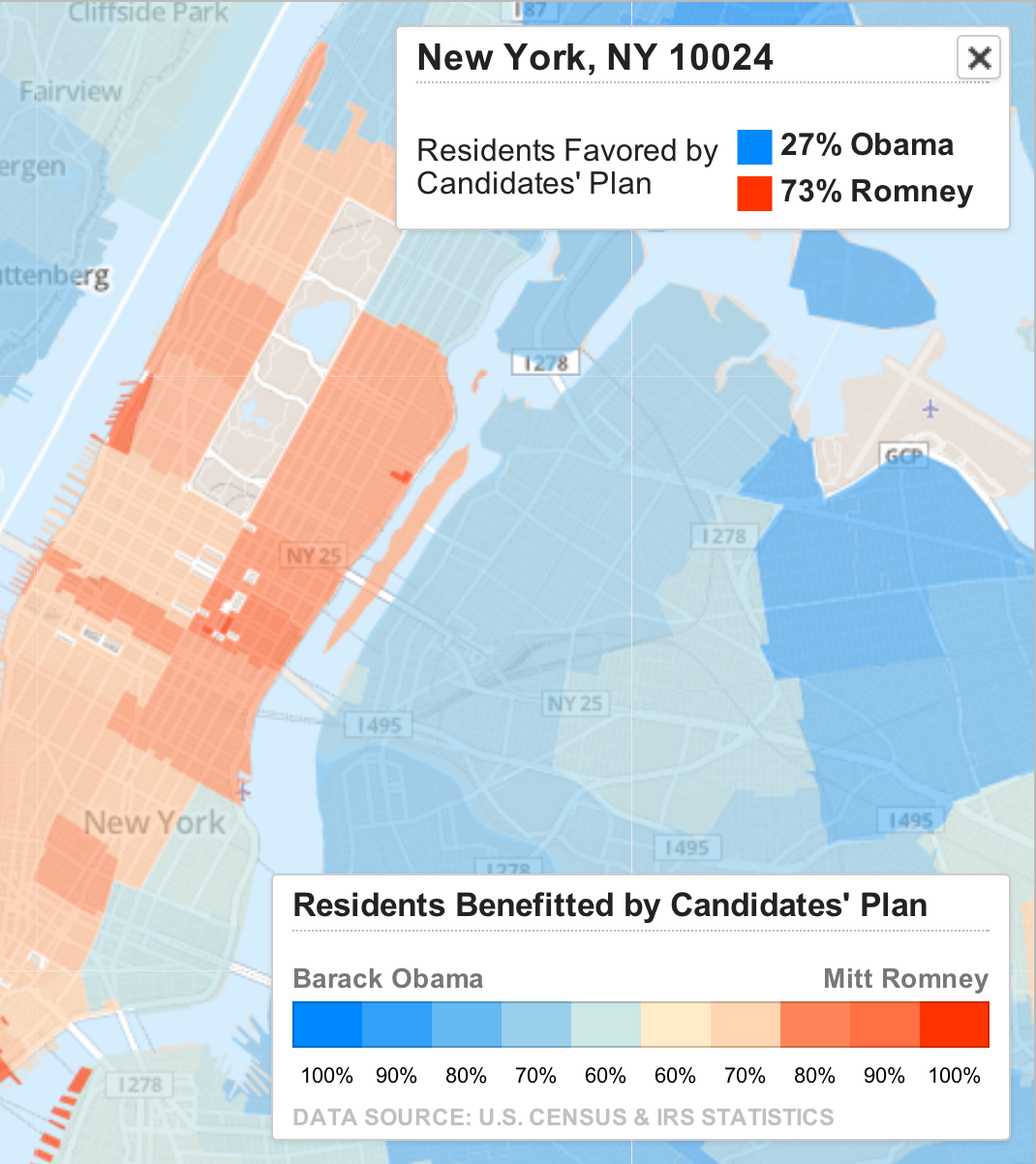

Inquiring voters can also zoom in on any neighborhood for more detailed snapshots.

Take the Upper West Side of Manhattan, where the median price of a home is $1.3 million. There, 73 percent of residents do better under Romney’s plan than Obama’s.

The same goes for liberal enclaves in San Francisco: in one tony area on the Bay, 67 percent of residents would take home more under President Romney.

Yet in the heartland, the economic map skews just as strongly towards Obama. It is almost impossible, for example, to find any large areas of Ohio that don’t fare better under Obama’s plan:

Ohio remains a key swing state, of course, precisely because it is not reliable Obama country. Bier believes that could change if his model goes viral.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

“If the candidates are clearly favoring your town and your household,” he says, “there’s very little reason you should vote opposite to that.”

Then again, Democrats have spent years asking people to stop “voting against their interests.” In the canonical 2004 book, What’s the Matter with Kansas, journalist Thomas Frank cataloged how Republicans convinced a generation of working-class voters to ignore their material interests in favor of “vague cultural grievances.” Through this “backlash culture,” Frank explains, the GOP campaigned on social issues but governed on “pro-business economics” once in office.

Could maps or data really change that dynamic for a digitally connected electorate?

After reviewing Politify’s model for The Nation, Frank said the new data is intriguing, but probably limited. For starters, he was wary “of placing a lot of faith in these maps” and he questioned whether one can “put a dollar ‘benefits’ value on the future presidency of the two candidates.”

Still, Frank found the national visualization “remarkable,” given its “inversion of the old Red State/Blue State maps of the last decade—apparently showing that people are voting almost entirely against their economic interests.” And while conservatives living in “an electronic world of their own” can brush off the analysis, Frank said the data could prove useful to reporters and open-minded voters alike.

“I can imagine how commentators could easily call up the economic consequences of a Congressional district going this way or that and using it to put a candidate on the spot,” he said. “The map’s seeming objectivity could make it very useful for local journalists, who are often confused by economic issues and unwilling to say what would be a more prosperous course for a given area.”

“When I wrote ‘Kansas,’ back in 2003, the word ‘politics’ was basically thought to be equivalent to the culture wars,” Frank recalled in an e-mail. “Now it looks like we might be headed toward erring in the other direction, concluding that politics is a dollar-value calculation.”

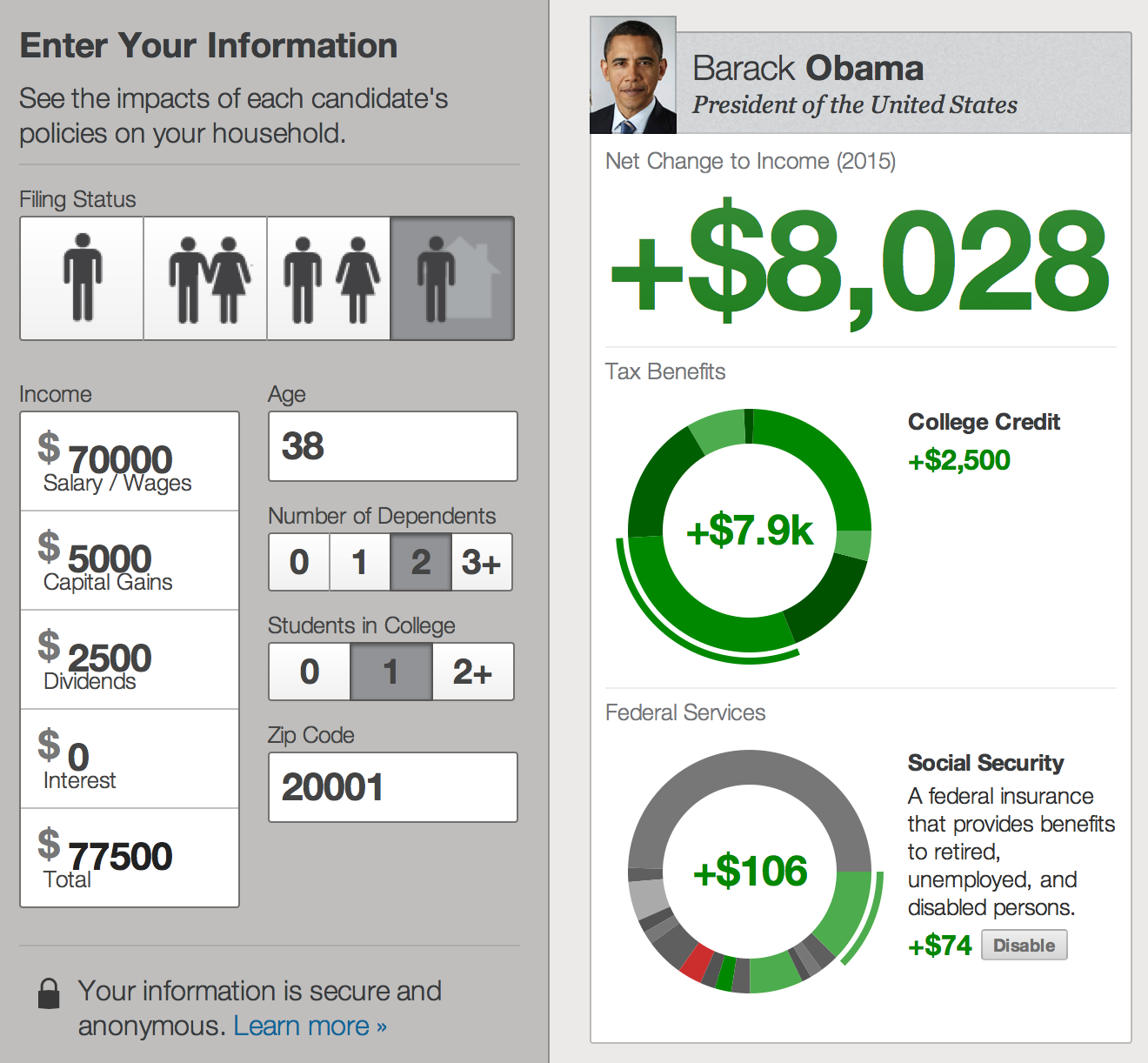

The Obama campaign agrees. It launched an online “tax calculator,” enabling visitors to see the return on their voting investment, which has already drawn over 60,000 likes on Facebook. (Romney’s tax information page is not interactive.)

At their core, however, most presidential campaigns at least aspire to an aspirational message, not pure self-interest.

“People are more than cost-benefit calculators,” said one veteran of Democratic presidential campaigns who assessed Politify’s maps (and is not authorized to talk on the record). Strong candidates connect to voters’ “non-financial instincts,” the operative said, and it is “enormously condescending” for Democrats to object that “working-class whites often vote against their economic interests.” The operative added, “If it’s OK for Warren Buffet to vote against his economic interests and vote his values, why is it wrong when a truck driver does it?”

In that sense, Politify’s personalized tool may be the least persuasive part of the program. It is all me, no we. (Pictured at right.)

One additional issue for the model, which conservatives are sure to stress if this approach gets attention, is its crabbed view of economic benefits.

Politify offers a static breakdown of taxes and government benefits frozen in time—without any modeling of potential economic improvement under the Romney plan.

But Republicans say their tax cuts will spur hiring and recovery, which they’d want factored into any objective assessment. That’s not a minor point. Imagine a Politify-style model for the 1980 race. It might favor Carter in the short term, but Republicans say Americans did better under Reagan’s long-term road from stagflation. Speaking for Politify, Bier says it is a valid point, but beyond the project’s scope. “There are policies,” he acknowledged, “that can impact the economy in ways that Politify doesn’t account for.”

Still, in a season of grand claims about taxes, entitlements, deficits and the largest downturn since the Great Depression, Politify is counting a lot, and inviting voters to inspect the results. It’s a start.