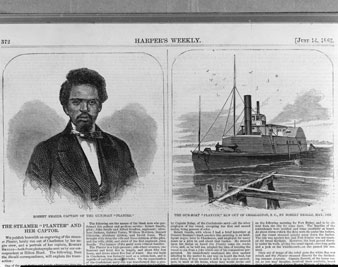

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs DivisionRobert Smalls and the Planter

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs DivisionRobert Smalls and the Planter

A few months ago, an article in The New York Times Magazine portrayed Barack Obama’s presidential candidacy as marking the “end” of traditional black politics and the emergence of a new generation of black leaders whose careers began after the civil rights struggle, and who strive to represent not simply black voters but the wider electorate. “For a lot of younger African-Americans,” wrote Matt Bai, “the resistance of the civil rights generation to Obama’s candidacy signified the failure of the parents to come to terms, at the dusk of their lives, with the success of their own struggle–to embrace the idea that black politics might now be disappearing into American politics in the same way that the Irish and Italian machines long ago joined the political mainstream.”

Bai’s analysis assumes that until recently only one kind of politics existed among African-Americans: a politics focused solely on race and righting the wrongs of racism. Yet divisions among black politicians are nothing new. Some politicians have defined themselves primarily as representatives of a black community; others have identified with predominantly white, nonracial parties like the Populists, Socialists or Communists. Some have been nationalists who believe that racial advancement comes only through community self-determination; others have worked closely with white allies. These differences go back as far as debates among black abolitionists before the Civil War. Then, as now, black politics was as complex and multifaceted as any other kind of politics, and one of the valuable implications of the new book Capitol Men (although its author, Philip Dray, does not quite put it this way) is that Obama’s candidacy represents not so much a repudiation of the black political tradition as an affirmation of one of its long-established, vigorous strands.

Of the thousands of men and women who have served in the Senate or as governors since the ratification of the Constitution, only nine have been African-American. Three of the nine hold office today: Senator Obama and Governors David Paterson of New York and Deval Patrick of Massachusetts. Well over a century ago, during the turbulent era of Reconstruction, they were preceded by another three: Hiram Revels and Blanche Bruce, both senators from Mississippi, and P.B.S. Pinchback, briefly the governor of Louisiana. The gulf between this trio and Obama, Paterson and Patrick is a striking reminder of the almost insurmountable barriers that have kept African-Americans from the highest offices in the land. It also underscores how remarkable, if temporary, a transformation in American life was wrought by Reconstruction. Revels, Bruce and Pinchback were only the tip of a large iceberg–an estimated 2,000 black men served in some kind of elective office during that era. The emergence of these men in the aftermath of the Civil War was living proof of an idea expressed after an earlier period of turmoil and bloodshed: “all that extent of capacity” of ordinary people, invisible in normal times, wrote Tom Paine in The Rights of Man, “never fails to appear in revolutions.”

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

For many decades, historians viewed Reconstruction as the lowest point in the American experience, a time of corruption and misgovernment presided over by unscrupulous carpetbaggers from the North, ignorant former slaves and traitorous scalawags (white Southerners who supported the new governments in the South). Mythologies about black officeholders formed a central pillar of this outlook. Their alleged incompetence and venality illustrated the larger “crime” of Reconstruction–placing power in the hands of a race incapable of participating in American democracy. D.W. Griffith’s 1915 film Birth of a Nation included a scene in which South Carolina’s black legislators downed alcohol and propped their bare feet on their desks while enacting laws. Claude Bowers, in The Tragic Era, a bestseller of the 1920s that did much to form popular consciousness about Reconstruction, offered a similar portrait. To Griffith and Bowers, the incapacity of black officials justified the violence of the Ku Klux Klan and the eventual disenfranchisement of Southern black voters.

Historians have long since demolished this racist portrait of the era. Today Reconstruction is viewed as a noble if flawed experiment, a forerunner of the modern struggle for racial justice. If the era was tragic, it was not because Reconstruction was attempted but because the effort to construct an interracial democracy on the ruins of slavery failed. Capitol Men begins by calling Reconstruction a “powerful story of idealism,” one Dray tells by describing the careers of the sixteen black men (including Hiram Revels and Blanche Bruce) who served in Congress between 1870 and 1877.

Popular histories like Dray’s, aimed at an audience outside the academy, have tended to infuse their subjects with drama by focusing on violent confrontations rather than the operation and accomplishments (public school systems, pioneering civil rights legislation, efforts to rebuild the shattered Southern economy) of the biracial governments established in the South after the Civil War. One thinks of recent works like Nicholas Lemann’s Redemption, a compelling account of Reconstruction’s violent overthrow in Mississippi; Stephen Budiansky’s The Bloody Shirt, a survey of violence during the entire period; and LeeAnna Keith’s The Colfax Massacre, about the single bloodiest incident in an era steeped in terrorism by the Klan and kindred white supremacist groups.

Dray’s previous books–well-regarded studies of lynching (At the Hands of Persons Unknown) and of the murder of three civil rights workers in Mississippi in 1964 (We Are Not Afraid)–fit within this familiar pattern. But in his latest work, Dray moves beyond violence, a vital but limited way of understanding the era’s political history. Perhaps because it concentrates on the careers of a few individuals, Capitol Men is episodic and somewhat unfocused. It does not really offer an assessment of Reconstruction’s successes and failings. Still, Dray is an engaging writer with an eye for the dramatic incident and an ability to draw out its broader significance and relevance to our own times.

One such episode involves Robert Smalls, who in 1874 was elected to Congress from Beaufort County, South Carolina. Twelve years earlier, Smalls had piloted the Planter, on which he worked as a slave crewman, out of Charleston harbor and delivered it to the Union navy, a deed that made him a national hero. In 1864, while the ship was undergoing repairs in Philadelphia, a conductor evicted Smalls from a streetcar when he refused to give up his seat to a white passenger. Ninety years before a similar incident involving Rosa Parks sparked the Montgomery bus boycott, Smalls’s ordeal inspired a movement of black and white reformers to persuade the Pennsylvania legislature to ban discrimination in public transportation.

Equally riveting is the 1874 confrontation between Alexander Stephens, the former vice president of the Confederacy, then representing Georgia in the House of Representatives, and another black South Carolinian, Congressman Robert Elliott. The subject of their exchange was a civil rights bill banning racial discrimination in places of public accommodation. Stephens offered a long argument based on states’ rights as to why the bill was unconstitutional. Elliott launched into a learned and impassioned address explaining why the recently enacted Fourteenth Amendment justified the measure (which was signed into law by President Grant the following year), then reminded Congress of an infamous speech Stephens had delivered on the eve of the Civil War: “It is scarcely twelve years since that gentleman shocked the civilized world by announcing the birth of a government which rested on human slavery as its cornerstone.” Elliott already had proved that he refused to be intimidated by whites: in 1869 he whipped a white man in the streets of Columbia for writing inappropriate notes to his wife. A black man assaulting a white man in defense of his wife’s good name was not a common occurrence in nineteenth-century South Carolina.

Many of the black Congressmen spoke of the abuse they suffered while traveling to the Capitol. Joseph Rainey was removed from a hotel dining room; Robert Elliott was refused service at a restaurant in a railroad station. Even when they reached Washington, hazards remained and insults swirled about them. A number of black Congressmen faced death threats and defended themselves by posting armed guards at their homes. In the House, one Virginia Democrat announced that he was addressing only “the white men,” the “gentlemen,” not his black colleagues. Another spoke of slavery as a civilizing institution that had brought black “barbarians” into modern civilization. Black Congressman Richard Cain of South Carolina responded that his colleague’s definition of “civilizing instruments” seemed to encompass nothing more than “the lash and the whipping post.”

The Congressmen Dray profiles came from diverse origins and differed in their approach to public policies. Some had been free before the Civil War, others enslaved. Some favored government action to distribute land to former slaves; others insisted that in a market society the only way to acquire land was to purchase it. Some ran for office as representatives of their race, others as exemplars of the ideal that, with the end of slavery and the advent of legal equality, race no longer mattered. Reconstruction’s black Congressmen did not see themselves simply as spokesmen for the black community. Blanche Bruce was one of the more conservative black leaders; yet in the Senate he spoke out for more humane treatment of Native Americans and opposed legislation banning immigration from China.

Like Obama, many of the sixteen black members of Congress discussed by Dray had enjoyed opportunities and advantages unknown to most African-Americans. Revels had been born free in North Carolina and later studied at a Quaker seminary in Indiana and at Knox College in Illinois. Bruce was the slave son of his owner and was educated by the same tutor who taught his white half-siblings. He escaped at the outset of the Civil War, organized a black school in Missouri and was a Mississippi newspaper editor and local officeholder before his election to the Senate. Some Congressmen had enjoyed unique privileges as slaves. Benjamin Turner’s owner allowed him to learn to read and write and to run a hotel and livery stable in Selma. Others, however, had experienced slavery in all its brutality. Jeremiah Haralson of Alabama and John Hyman of North Carolina had been sold on the auction block.

None of these men fit the old stereotype of Reconstruction officials as ignorant, incompetent and corrupt. All were literate, most were seasoned political organizers by the time of their election and nearly all were honest. One who does fit the image of venality was Governor Pinchback of Louisiana, whose career combined staunch advocacy of civil rights with a sharp eye for opportunities to line his pockets. Pinchback grew up and attended school in Cincinnati. In the 1850s he worked as a cabin boy on an Ohio River steamboat. He fell in with a group of riverboat gamblers and learned their trade. He turned up in New Orleans in 1862 and expertly navigated the byzantine world of Louisiana’s Reconstruction politics. Pinchback was undoubtedly corrupt (he accumulated a small fortune while in office) but also an accomplished politician.

Reconstruction ended in 1877, when President Rutherford B. Hayes abandoned the idea of federal intervention to protect the rights of black citizens in the South, essentially leaving their fate in the hands of local whites. But as Dray notes, black political power, while substantially diminished, did not vanish until around 1900, when the Southern states disenfranchised black voters. Six more African-Americans served in Congress before the end of the nineteenth century. Some of their Reconstruction predecessors remained active in politics. Robert Smalls, of Planter fame, served as customs collector at Beaufort until 1913, when he was removed as part of a purge of blacks from the federal bureaucracy by Woodrow Wilson, the first Southern-born president since Reconstruction.

Pinchback and Bruce moved to Washington, where they became leaders of the city’s black elite and arbiters of federal patronage appointments for African-Americans. Bruce worked tirelessly but unsuccessfully to persuade Congress to reimburse blacks who had deposited money in the Freedman’s Savings Bank, which failed during the Panic of 1873. Like Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac in our own time, the bank was a private corporation chartered by Congress that enjoyed the implicit but not statutory backing of the federal government. Its counterparts today are being bailed out with billions of taxpayer dollars, as they have been deemed too big to fail. The Freedman’s Savings Bank was too black to rescue.

The last black Congressman of the post-Reconstruction era was George White of North Carolina, whose term ended in 1901. From then until 1929, when Oscar DePriest took his seat representing Chicago, Congress remained lily-white. Not until 1972, with Andrew Young’s election in Georgia and Barbara Jordan’s in Texas, did black representation resume from states that had experienced Reconstruction. Today the Congressional Black Caucus numbers forty-two members, seventeen of them from the states of the old Confederacy. But the pioneering black predecessors have been all but forgotten. I know of only two examples of public recognition in their home states–a school named for Robert Smalls in Beaufort and a Georgetown, South Carolina, park named for Joseph Rainey. Reconstruction’s Capitol men deserve to be remembered, not least because without the political revolution they embodied, it would be impossible for a black man today to be a candidate for president.