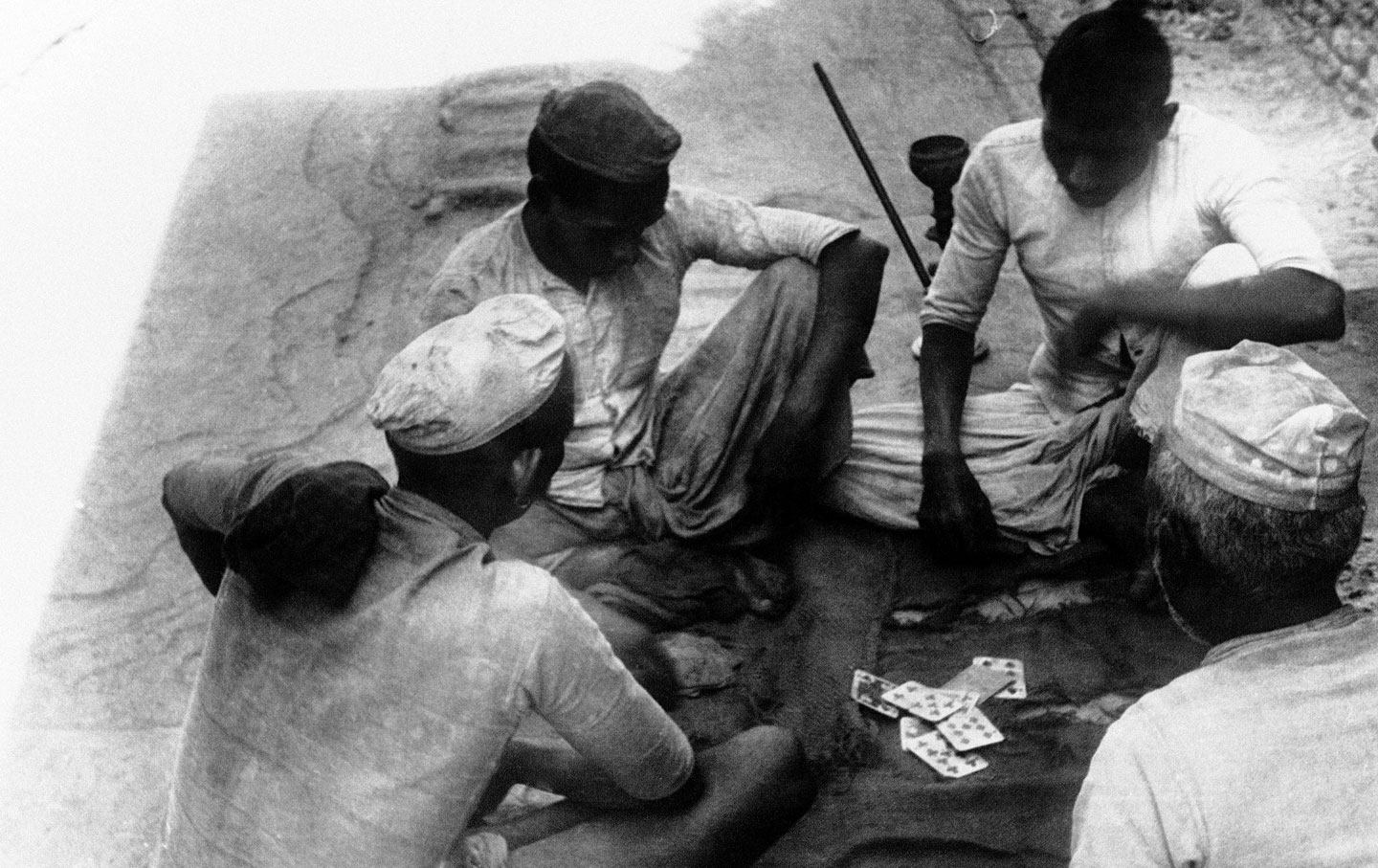

A group of card players in Mysore, India, 1931.(AP Photo)

The Kannada-language writer U.R. Ananthamurthy was born in 1932, in a village outside Thirthalli, a town in southwest India. His childhood, today, is scarcely imaginable. In a 1989 essay, Ananthamurthy described his village as a medieval colony cut off from scientific progress and governed by priests, a world where myth “had an unbroken continuity with reality.” It was also surrounded by tigers.

But that image of hermeticism is only partly true: Progress had by then reached the surrounding towns. The net result was a sort of time warp. In the morning, Ananthamurthy would hear the local priests debate whether the earth orbited the sun. In high school, he was lectured by a science teacher who “argued that the Bhagavadgita was after all fiction.” Walking home, he stopped to listen to the only man who owned a radio discuss Bertrand Russell and George Bernard Shaw. “Within a single day,” he wrote, “I traversed several centuries. The linear time of the West co-existed in India—the ancient, the primitive, the medieval, and the modern—often in a single consciousness.”

Ananthamurthy’s hybrid existence led to an early self-reckoning. Looking at his society through enlightened eyes, he saw a local Brahminism that had grown decadent, hypocritical, and backward-looking—one that was now frankly unfeasible for the modern world.

Books eased his disillusionment, or rather eased him into it. Though remote from urban centers, the Thirthalli of Ananthamurthy’s childhood “was very literary.” And wrestling with questions of faith and rationalism, of roots and progress, he found guidance in socially engaged novelists like Shivarama Karanth and poets like Kuvempu and D.R. Bendre. These writers held heretical opinions—Karanth, for example, had written about “untouchables” and even married outside his caste—but were still respected by conservatives and priests. They comprised a sort of parallel social order, one that could criticize society from within. For Ananthamurthy, they offered a model “of belonging to a community with which I could quarrel as if it were a quarrel with myself.”

After completing high school, Ananthamurthy earned a BA and an MA in English literature at the University of Mysore. Then he moved to the University of Birmingham for further study. It was there, halfway across the world, that the idea for his first novel occurred to him. The spark of inspiration was Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal. The film’s medieval setting took Ananthamurthy back to his own village. He imagined its hero’s Christian spiritual crisis as a Brahmin’s loss of faith, which was really a stand-in for his own. Decades later, he would describe Samskara: A Rite for a Dead Man, which was reissued by NYRB Classics this January, as an attempt to reconcile his “upbringing in a Brahmin family” with his education, “which set me on a journey away from my roots.”

Originally published in Kannada in 1965, Samskara provoked controversy and became a success when its English translation was serialized in The Illustrated Weekly of India a decade later. Certain Brahmin communities felt that Ananthamurthy’s depiction of them was treacherously negative. For V.S. Naipaul, their outrage, though a “political simplification,” proved the novel’s acuity. Indeed, he thought that Ananthamurthy had captured a national zeitgeist: Samskara, he wrote, “takes us closer to the Indian idea of the self.” But Naipaul’s claim is itself a political simplification. India is a country of diverse religions and ways of being; it makes little sense to speak of a national “self.” (Though if there were such a thing, Naipaul would have best defined it.) A better explanation for Samskara’s appeal is perhaps found in history.

In the preface to Temptations of the West (2006), his collection of reporting from South and Central Asia, Pankaj Mishra observed that Western ideologies confronted the region with a single challenge: “modernize or perish.” For people “with traditions extending back several millennia,” Mishra found, this process of “remaking life and society in all their aspects (social, economic, existential) frequently collapsed in violence.” Newspapers have familiarized us with the collective violence he’s referring to: the massacre of Muslims in Gujarat, the Taliban, 9/11, Nepali Maoism. What’s harder to grasp, and perhaps more important, are the mutinies that rage within common people caught between cultures. Two such mutinies lie at the heart of Samskara. With equal sympathy and ruthlessness, Ananthamurthy gives them shape.

Samskara opens with a ritual of cleaning. “He bathed Bhagirathi’s body, a dried-up wasted pea-pod, and wrapped a fresh sari around it; then he offered food and flowers to the gods as he did every day, put flowers in her hair, and gave her holy water.”

“He” is Praneshacharya, the head priest of an agrahara, a Brahmin village. Bhagirathi is his wife. That first sentence, so devastating in its rejection of eros, would suggest that the couple is very aged; in fact, they haven’t reached 40. Bhagirathi was born physically disabled; their 20-year marriage has been more of a doctor-patient relationship than a pact between lovers.

We must admit, however, that a certain form of love, or at least affection, is suggested by the diligence with which Praneshacharya beautifies his wife “every day.” And once we learn of his renown—that as a “Crest-Jewel of Vedic Learning,” he was considered the village’s most eligible bachelor—we might even come to respect, within the context of patriarchy, his devoted concern for his wife.

But there’s a problem with Praneshacharya’s concern: It’s fundamentally self-serving. He didn’t marry Bhagirathi in spite of her condition; he married her precisely because of it. It was a calculated act of penance, a sort of glorious abstinence. Rejecting the beautiful wife promised to him by his Brahmin birth is a means for Praneshacharya of hastening his own salvation. “By marrying an invalid,” he thinks to himself, “I get ripe and ready.”

Praneshacharya’s greedy abstinence reflects a larger societal tendency. By incentivizing belief, the members of his agrahara have wrung it of all spiritual meaning. They follow the dictates of religion with hairsplitting accuracy. (And these dictates govern everything from the private practices of eating and sex to the public laws of commerce and inheritance.) But instead of creating a just society, this only breeds twisted forms of pettiness and greed. Every man desires one thing: to be recognized as the purest Brahmin. And every woman wants to be that purest Brahmin’s wife. (Notably, though, Bhagirathi’s perspective is entirely absent from the book.) A society this shallow and self-indulgent offers little resistance to modernity: It has no scientific development, no serious economic opportunities, is brutally unequal (the caste system is entrenched) and organized around fear. Once the outside world breaches its seclusion, you suspect it will collapse.

The outside world arrives in the form of Naranappa, a rogue Brahmin who escapes the agrahara and encounters the Indian National Congress. (No date is specified, but contextual hints place Samskara in the 1930s or ’40s.) Naranappa returns to the village as an obsessive heathen. We learn through a flashback that he has systematically violated every Brahmin law: He abandoned his wife and took up with a Dalit prostitute; he invited Muslims to the agrahara; he fished in holy waters, gave alcohol to a relative’s son, ate meat… the list goes on.

As in Bergman’s early works, Samskara’s characters have an allegorical bent. In fact, they fall into pairs. Naranappa, with his heretic hedonism, is the anti-Brahmin; the learned and kind Praneshacharya, despite his marital hypocrisy, represents the best of Brahminism. Who will prevail when the two clash? We can’t know, because Ananthamurthy kills Naranappa on the second page—a startling death that accomplishes many things.

On the simplest level, it sets Samskara’s plot in its cyclical motion. No one can eat until Naranappa is buried, but his relatives won’t bury him for fear of inheriting his sins. Praneshacharya retreats to his books to find an answer. Until he does, or until someone else can be found to fulfill the rites, the village is suspended in mounting fear and hunger.

The resultant stasis allows Ananthamurthy to present a rich portrait of a society on the verge of collapse. Naranappa’s corpse in fact becomes a dark mirror to the agrahara. In its cruelty, superstition, and ultimate helplessness, the village’s collective response nicely sums up its social state:

Not a human soul there felt a pang at Naranappa’s death, not even the women and children. Still in everyone’s heart an obscure fear, an unclean anxiety. Alive, Naranappa was an enemy; dead, a preventer of meals; as a corpse, a problem, a nuisance.

This section of Samskara is a priceless historical record. As Naranappa’s corpse rots, the narrative circles around the local community, from one consciousness to the next, presenting worldviews now entirely forgotten and, to younger generations, never known. Ananthamurthy’s technique is essentially cinematic: In a series of brief sections, he swivels among the villagers, entering their minds in the close third person, creating a mosaic or a social panorama of individual portraits. It’s a bravura performance, reminiscent of Gabriel García Márquez’s Chronicle of a Death Foretold, though Ananthamurthy’s task was perhaps harder given his novel’s almost premodern setting.

Indeed, modern readers will find it especially thrilling to encounter greedy women and craven men who inhabit a cyclical time untouched by the march of progress. Perhaps relatedly, one is struck by their tremendous lack of ambition. These villagers have almost no curiosity about the outside world, which for them is a source of impurity, not enlightenment. If anything, their greatest desire is to return to an earlier equilibrium.

As Ananthamurthy sketches his portraits, strange events pile up. Dead rats appear in houses. Vultures descend on roofs. People fall sick and suddenly die. And here Naranappa’s corpse reveals its third function: Before his death, he traveled to a nearby town, where he caught the bubonic plague. Unchecked, the disease now spreads across the agrahara. In a cruel irony, the villagers interpret the resultant deaths as a spiritual plague.

Their misunderstanding reveals religion’s practical irrelevance. And a similar lesson is being learned by Praneshacharya. After a two-day starved vigil, he secludes himself in a temple, swearing to leave only when he receives a sign from God. He meditates all day, but no sign is forthcoming. He emerges exhausted, despairing, full of doubt. Returning home to provide his wife medicine, he meets Chadri, Naranappa’s “untouchable” Dalit lover. She is attracted to his goodness. They stumble into having sex.

Like Naranappa’s death, this bizarre sex scene is crucial. It forces Praneshacharya out of his agrahara: Soon after the coupling, he learns of his wife’s death from the plague; dazed, he wanders into the forest with no plan. It also represents Praneshacharya’s ejection from—or is it a rejection of?—Brahminism: He feels transformed by sex, and the transformation overturns the Brahmin principles he’s adhered to all his life. Taken together, these changes symbolize a belated victory for Naranappa: Praneshacharya has succumbed to the temptations and turned heathen.

Subsequent events are rather surprising. You would expect the impulsive sex scene to fill Praneshacharya with painful guilt or fervid curiosity. Instead, as Naipaul has observed, he’s overcome by “a sudden neurotic uncertainty about his nature.” The uncertainty arises from a question of free will: The coupling was impulsive, perhaps the only impulsive act of Praneshacharya’s life. But since it was purely impulsive, is he really accountable for it? If so, how is he to account for all the instincts he has suppressed all these years?

This quasi-mystical enquiry represents Ananthamurthy’s attempt to reconcile tradition and modernity—or rather to declare a pox on both houses. In an interview included in NYRB’s new edition, he claims that Praneshacharya and Naranappa (who is eventually cremated by a Muslim, bringing that crisis to an abrupt end) are two sides of the same coin. They both embody free will, the latter through his heresies, and the former through his regulated belief. Both parties, Ananthamurthy then argues, are misguided, because “any person who lives in willfulness is a person who lives in bad faith.”

To provide a counterpoint, he introduces Putta, a truly aimless and godless hustler who follows Praneshacharya around on a whim for the second half of the novel. Translator A.K. Ramanujan, a celebrated Indian poet, writes in his excellent afterword: “Putta is a denizen of the world…. [H]e is so completely and thoughtlessly at one with this world that he is a marvel.” It’s an interesting idea, this purely instinctual life, but Putta is too slim a character to epitomize anything so grand. More childish than instinctual, he is finally just unmemorable.

Samskara thus ends somewhat inconclusively, with Praneshacharya returning home “anxious, expectant.” In a bitter way, that’s apt. Just as Praneshacharya fails to formulate a new worldview after losing faith, Ananthamurthy fails to find a new form after demolishing Brahminism. His novel, like his protagonist, grows formless and confused after encountering the wider world.

“Modernize or perish,” Mishra declared—and in a socioeconomic context, he’s right. But Samskara suggests that on the personal level, that’s a false choice: Praneshacharya’s spiritual loss is more crippling than enabling. And for all his bloviating talk of progress, Naranappa modernizes and perishes.

Ratik Asokanis a writer in New York.