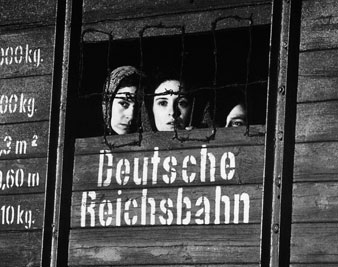

Universal Pictures/Everett CollectionEmbeth Davidtz (center) in Schindler’s List, 1993.

Universal Pictures/Everett CollectionEmbeth Davidtz (center) in Schindler’s List, 1993.

From a book by Thomas Keneally, who had stopped in a luggage shop to purchase a briefcase, and while waiting for credit card approval was convinced by the shopkeeper to look at some old documents he kept in the back of his store. The owner was one of the 12,000 people saved by Oskar Schindler.

Tidings of comfort and joy, brave moviegoers! You’ll need them this holiday season, because the choices boil down to two. You can see a droll animated fantasy called The Nightmare Before Christmas, devised by Tim Burton and directed by Henry Selick; or you can see “The Nightmare Before Christmas,” meaning everything else out there.

Drop by the multiplex and take your pick: the Nazis wiping out the Krakow ghetto, or Tom Hanks developing lesions and wasting away—or hey, how about two hours’ worth of a Vietnamese woman being raped, tortured and terrorized? The very best of the December releases, Mike Leigh’s extraordinary Naked, is scary enough to scorch off your eyebrows. (It’s a small-budget, limited-run picture, so I’ll save it till the end of this review.) And the season’s Major Motion Pictures? Due to the swelling of directorial egos, the shortness of memory of Oscar voters and the richness of the December box office, our theaters are now full of prestige films—meaning lavish excursions into wide-screen suffering. These being the likely options in your neighborhood, I would advise you most seriously to stick with Steven Spielberg for his tour of the Krakow ghetto. It’s the most estimable of a strange, and strangely unfestive, batch of holday films.

At first glance, Schindler’s List (novel by Thomas Keneally, screenplay by Steven Zaillian) is not the sort of material that cries out for Steven Spielberg; the Holocaust, as I understand it, does not need to be juiced up with visceral excitement. And in fact, there are a few moments—a handful, out of a three-hour film—in which Spielberg does push the story into melodrama. As for the rest, though, Schindler’s List has a real and unexpected integrity. Filmed in black and white for a quasi-documentary look (and to avoid flooding the screen in slasher-movie red), the picture for the most part presents brutality in the middle distance, under a steady, matter-of-fact gaze. Horror piles up on horror with the indifference characteristic of Nazism. To cite one example among many: There is a scene in which the camp commandant (portrayed in astonishing depth by Ralph Fiennes) takes target practice from his balcony. He picks off several Jews at random, then calmly goes on to his setting-up exercises, using the still-warm rifle to help him stretch.

Unfortunately, Fiennes is not the lead actor in Schindler’s List. Liam Neeson is, and that’s where the movie becomes problematic. A big, handsome lug, Neeson looks just right to play Schindler, the real-life German entrepreneur who found in Nazi-occupied Poland a business climate in which at last he could not fail. It seems Schindler’s one talent was his sociability; as he’s embodied by Neeson, you can see why soldiers and profiteering officials would warm to his company. What you don’t see, given Neeson’s opaque performance is the process by which Schindler gradually became driven to protect “his” Jews, ultimately rescuing more than a thousand. Spielberg, too, must be charged with this opacity—he’s never had any interest in mere people and so has never learned the tricks of developing characters. But is this a fault in Schindler’s List? I think Spielberg has in fact converted his incapacity into the virtue of reticence. Schindler should be an enigma. We in the audience are never allowed the comfort of believing that we understand this man—let alone that we would match his heroism.