Handsel BooksAngel Wagenstein

Handsel BooksAngel Wagenstein

In Joshua Cohen’s “Untitled: A Review,” the opening story of his brilliant but unheralded debut collection, The Quorum, a critic from “one of our more respected publications” is stunned into submission by a mammoth box appearing on his doorstep. Inside the package our hero discovers a book of more than 6 million blank pages–“pure, virgin white, like the snow around Auschwitz”–lacking pagination, footnotes, author credit, introduction, copyright, dedication, colophon or any other identifying marks. The necessity (and impossibility) of a response to this monumental blank–a nothing that is not and a nothing that is–drives the critic into a paranoid raving fit, but in his review of the untitled tome he steers himself toward a confident conclusion:

In intent and execution this history without a title, this Untitled by Anonymous, is the best record of, and commentary on, the Holocaust this reviewer has yet encountered, the best in or out of print produced by, and in, the last half-century. Just as that noble laureate Elie Wiesel filled the need for a new word (holocaust: complete consumption by fire) for a new horror (the Holocaust), this anonymous author–if this massive thing even has an author–has found the only way to write about the event, the idea. Or not.

There’s no only way to write about the Shoah–but there are many ways one shouldn’t write about it. Cohen’s imagined nonfiction chronicle is the perfect antithesis of the now-traditional Holocaust narrative, the kind that focuses on great escapes, improbable heroes, loathsome villains and superhuman acts of kindness. “It is not mawkish. It is not patronizing. It’s not insulting.” This masterpiece by Anonymous provides a textbook definition of negative capability, as direct as a math equation: n6,000,000 = x. “The word is sacred,” writes the critic in his review. “Words strung together are not.”

The attempt to find new words for a new horror aptly summarizes the past sixty years of Jewish fiction, and is the obverse of the stark, unapproachable purity of Untitled by Anonymous, or of T.W. Adorno, who declared in 1949 that “to write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric.” Nearly every modern Jewish writer of merit has contested Adorno’s judgment. And once poetry is fair game, is commerce ever far behind? On a recent visit to the local multiplex–to see a popular mainstream entertainment about the death of God, no less–I counted four movie trailers about the Nazis. One was a vigilante movie, another a spy thriller, the next a May-December romance, the last a sentimental product for children.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

Creating a book of 6 million blank pages, or a movie of 6 million frames of unexposed film, seems untenable, and not every Jewish author (or director) has the imagination or inclination to mint forms unique to this Subject of Subjects. World War II and its aftermath is the Jewish historical narrative of the past century–in a sense the only story worth telling–and its myriad channels of significance have proven to fit any plot, any genre, mostly without causing awkward ethical misgivings. As New York Times film critic A.O. Scott grimly noted, in a cautionary essay about this winter’s slate of Holocaust movies, the Oscar sweep of Spielberg’s Schindler’s List helped to “domesticate” the Shoah for middlebrow audiences, making “the Holocaust…more accessible than ever, and more entertaining.” We are now bearing the low-hanging fruits of this entertainment–such as Angel at the Fence, the sickly sweet, Oprah-approved Holocaust romance memoir recently exposed by The New Republic as a fabrication, the logical endgame of this cultural development.

But we are also reaching a crucial stage in modern Jewish storytelling, when the survivors of the Jewish people’s defining struggle are issuing their final missives. Witness and its interpretation are giving way to a reckoning. Those last few testaments are landing on our doorsteps–the next sentences are waiting to be written. Former Knesset speaker Avraham Burg, in his recent disquisition The Holocaust Is Over; We Must Rise From Its Ashes, argues that–for the purposes of peacemaking–letting go of the past is preferable to misappropriation. “We have pulled the Shoah out of its historic context,” he writes, “and turned it into a plea and generator for every deed. All is compared to the Shoah, dwarfed by the Shoah, and therefore all is allowed…. All is permitted because we have been through the Shoah and you will not tell us how to behave.”

Aside from the indisputable value of witness testimony–each new tale an essential accrual of evidence, a bulwark against organized forgetting–the richness of World War II literature is that every survivor story is a universe of drama unto itself, and no two survivor stories are the same. There is a survivor story–and here I blanch at what already sounds like a genre–to elicit every possible response, all valid except apathy. To lift the Shoah out of its historical context is a mistake, especially since that context remains so overwhelming and so incomplete. One cannot rise from the ashes without bearing their smudge.

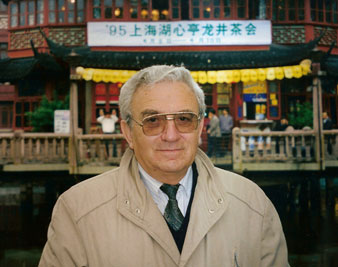

In the annals of war, the biography of Angel Wagenstein, an 86-year-old Bulgarian Jewish novelist and screenwriter whose books are just now making their way to the United States, is noteworthy only for its convoluted narrative. Returning to Bulgaria as a teenager after his family’s brief sojourn in France, he joined an underground antifascist brigade, was sent to a Nazi labor camp, escaped the camp, rejoined the Bulgarian partisans, got arrested again and then was condemned to death just as the Red Army stormed Bulgaria in 1944, saving his life. Wagenstein’s debut novel, Isaac’s Torah: Concerning the Life of Isaac Jacob Blumenfeld Through Two World Wars, Three Concentration Camps and Five Motherlands–written in 2000 but published in English last year–offers much of the same absurdist (and seemingly arbitrary) historical sweep as the author’s saga.

A mock epic set in unambiguously epic times, Isaac’s Torah embodies the humanistic notion that even the most unprepossessing life story should be bound like a Bible. Buoyed by a knockabout levity, like a shtetl cousin to Forrest Gump or Jaroslav Hasek’s The Good Soldier Svejk, Wagenstein’s picaresque story portrays Jewish humor and Jewish wisdom as inextricable twins and time-tested agents of survival. If Isaac, the narrator, has trouble getting from point A to point B, and if his countless jokes and Hasidic fables (nimbly translated from the Bulgarian by Elizabeth Frank and Deliana Simeonova) sometimes seem beside the point… well, isn’t digression just another way of molding oneself in God’s image? After all, “the Holy God, glory to His name, has more than once deluded you and promised things that He might have intended to fulfill, but was then distracted by other things and forgot. But you haven’t even for a second come to doubt His glory, you’ve searched for extenuating reasons or consolations of the God-delays-but-doesn’t-forget or God’s-mills-grind-slow variety. Or don’t you think so?” Unlike God’s brilliant but unfocused Pentateuch, Isaac’s Torah–for all its fits and starts–is mostly Exodus. And like his biblical namesake, Isaac finds himself singled out by the heavens as a human sacrifice, only to be saved from the chopping block through the same divine providence.

Our raconteur begins life as a modest tailor in Kolodetz, a village near Lvov. Over the course of a half-century and two world wars, ownership of Kolodetz will be passed among the Poles, the Soviets, the Nazis and seemingly any other occupying force willing to take an interest. If this relentless global struggle is being waged with the force of coherent ideologies, Isaac is none the wiser. As with I.B. Singer’s elders of Chelm, displays of common sense by Wagenstein’s fools illuminate the follies of ideological conflict. Isaac’s spiritual guide, closest friend and brother-in-law is the Marxist rabbi Shmuel Ben-David, who runs both the Kolodetz shul and its Atheists’ Club. In an early sermon, he works up a righteous fury:

It’s all stupidity…. Why am I here, I’m asking you? To guide you and take care of your souls, so that when you die, you’ll go all clean to our God Yahweh, eternal be His glory. The same is supposed to be done by my colleagues–Catholics, Adventists, Protestants, Orthodox, Sabbatarians, and Muslims–to honor the emperor and for the glory of their own God. And what’s the point, I’m asking you? When I know that on the other side of the front line there’s a fellow rabbi who’s guiding our boys–who can tell me now if they’re ours or not ours?–to fight against you, to kill you for the honor of their own emperor and for God, eternal be His glory. And then the war will end, and when the plows begin plowing all through Europe, and your bones come up shining white in the fields, ours and not-ours, all intertwined, then nobody will know for what God and which emperor you died.

That the rabbi appears to be reading a chapter of the Pentateuch from an open prayer book is, to Wagenstein, an important detail.

If this jaunty, sentimental novel can be called a work of historical revisionism, it’s only because Wagenstein focuses exclusively on the outliers of World War II. When depicting would-be heroes and supposed villains, he’s only interested in the exceptions that prove the rule. While history continues its inexorable sweep somewhere in the background, enacting the tragic saga that casual readers should already know by heart, Isaac consorts with indifferent Nazis, sensitive Russians and likable Poles. Everyone receives the benefit of the doubt. In his labor camp’s Nazi lieutenant, Isaac can “detect distant notes of good intentions.” Another gentleman is described as “a decent and noble anti-communist, with a barely perceptible Polish streak of anti-Semitism–something like a good aged wine with a bitter aftertaste.”

To call Isaac’s Torah unserious would be to fundamentally misunderstand Wagenstein’s designs. Even as survivors bear the weight of their history, it’s still incredibly difficult to remember sensations of pain. Looking back on the recent past, Isaac Jacob Blumenfeld has decided that all men are brothers, all enemies temporary and easily replaced. And official history should be left to official historians. Every time Isaac begins to dispassionately recount the steps toward the Final Solution, he stops himself: “We were politely informed that during a three-day period all communist functionaries, Jews, and Soviet officers in hiding were supposed to register at command headquarters, or else, according to wartime rules, they were going to be…. Well, shall I tell you, or can you guess yourself?” When Isaac’s wife, family and friends perish–the book is unsparing, as it must be, in this respect–we feel the weight of their disappearance, a sense memory even more tactile than hatred for the evil forces responsible for their murders.

Wagenstein’s third novel, Farewell, Shanghai, was published in English in 2007, and it’s easy to see why it preceded Isaac’s Torah on these shores. Drawing on his experience as a screenwriter, Wagenstein fashioned a sweeping cinematic melodrama that depicts an exotic and little-known chapter of Jewish history–the story of the Shanghai ghetto. (A 2002 documentary film by Dana Janklowicz-Mann and Amir Mann remains the best primer on the subject.) As an “open city” at the beginning of World War II, Japanese-occupied Shanghai became a safe haven for European émigrés and Jewish refugees. A modern-day Babylon, wartime Shanghai was a polyglot, destitute, filth-ridden city where the escaped Jews, who numbered 19,000 by 1941, lived mainly in dilapidated shacks. In the early years of the war, the refugees were assisted by a community of anticommunist Russian and wealthy Baghdadi Jews–the latter of whom arrived in the mid-nineteenth century, establishing a new outpost of a burgeoning Sephardic import/export empire. The refugees arrived before the bombing of Pearl Harbor brought the Americans into the war, and Nazi influence to Shanghai, and… well, shall I tell you, or…?

Narrated by an omniscient spectator who slips into third person after a brief introduction, the panoramic story of Farewell, Shanghai alights upon all of the city’s wartime social strata, with vivid characters whose activities–including epic gestures of romance, espionage and betrayal–necessarily sidestep the good/evil dichotomy. In a book that bears almost no stylistic resemblance to Isaac’s Torah, Wagenstein retains his focus on historical outliers. The Japanese leadership is pitiful rather than malicious, and one of our heroines is a beautiful blond Jew who idolizes Leni Riefenstahl and ends up employed by the Nazis. And naturally, the Shanghai ghetto features a heretic rabbi of its own, who leads Sabbath services in a Buddhist temple. When asked about the oneness of the Jewish God, he responds, “To tell the truth, I don’t know anymore…. How are the Chinese worse than us? Or, let’s say the Hindus, or the Polynesians? Why should their gods be false, untrue, and our own the real one and the only one?… People feel the need to believe. Let’s leave them to do it as they wish.”

Part of what makes this otherwise conventional historical epic unusually compelling is that its characters are shielded from the truth of their situation. Scraping by in claustrophobic and unsanitary ghetto conditions while laboring for minimal rations, the surviving Jews of Shanghai would only later discover that, relatively speaking, they were actually citizens of paradise. Wagenstein’s late-life historical-fiction project is built upon this very paradox: to survive is to endure along with unshakable images of horror, but it’s also the greatest gift imaginable.

In the end, most of the principal characters in Farewell, Shanghai are killed–many during an American bombing campaign. Even in a sanctuary city, the hand of fate acts with arbitrary mercilessness, aided by the banality of evil. Referring to the Japanese and, perhaps by extension, the majority of Nazis, Wagenstein sees wartime atrocities as “millions of small faults–composed of silence, indifference, obedience, myths of military honor.”

One can esteem the impossible orthodoxy of Untitled by Anonymous and still find merit in Wagenstein’s radical humanist agenda. Like the skeptic but soulful rabbis who lend his stories a spiritual current, the author recognizes that apostasy leads to unfamiliar but equally relevant truths. “In this inhuman battle, was it only a question of the evildoers and the righteous?” the narrator of Farewell, Shanghai asks. “Futile questions without an answer. Or with a thousand different answers.” Or, in a just world, with 6 million.

It would be a shame to leave those pages blank.