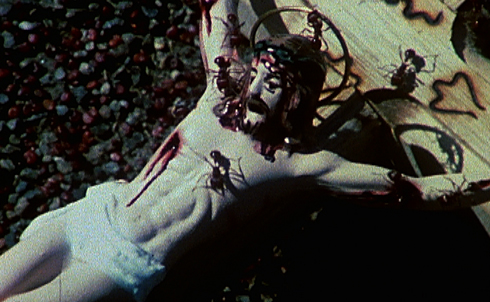

This past November 30, the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery unceremoniously pulled David Wojnarowicz’s film A Fire in My Belly from an exhibit after complaints from conservatives and Catholic groups. As The Nation’s Doug Harvey explains, House Speaker John Boehner threatened to cut Smithsonian funding if the exhibit wasn’t axed, and Eric Cantor called the film—which contains an eleven-second sequence showing a crucifix crawling with ants—an “outrageous use of taxpayer money and an obvious attempt to offend Christians during the Christmas season.”

But this wasn’t the first time artists and their work have come under attack from American conservatives. Attempting to cut funding for the arts and silence controversial artworks has long been a favored wedge initiative for the right, and politicians have often used campaigns against artists as cover for secretly homophobic, sexist or otherwise socially conservative ends.

Credit: Courtesy of The Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P.P.O.W Gallery, New York and The Fales Library and Special Collections/ New York University

When the Mexican communist muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros came to Los Angeles in 1932, he was commissioned to produce a work for a large wall in the Olvera Street district. But his pointed mural, featuring “a Mexican peasant crucified under an American eagle,” didn’t sit right with local elites and was “whitewashed within a year—allegedly by order of the downtown Anglo business community.”

Credit: © 2011 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / Sociedad Mexicana de Autores de las Artes Plásticas

In the late 1980s, a right reinvigorated by years of Reaganite social-economic policies reanimated the culture wars by taking aim at artists. One of their first targets was photographer Robert Mapplethorpe, whose stately studio compositions, which Nation critic Arthur Danto called “high-style, high-glamour” still lifes, featured nudes and depictions of BDSM feats.

In 1989, conservatives forced the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, DC to cancel an exhibit of Mapplethorpe’s photographs, and the next year the director of the Contemporary Arts Center of Cincinnati faced obscenity charges for hosting the exhibit. The exhibit went forward nevertheless, attracting the highest attendance in the Center’s history, and the right turned to other targets.

Credit: AP Images

Andres Serrano’s “Piss Christ” is an instantly recognizable icon of controversial art, largely because of the furor right-wing politicians and pundits whipped up over the photograph. Senator Jesse Helms was outraged by it, Senator Al D’Amato called it a “deplorable, despicable display of vulgarity” and religious leader Donald Wildmon said it amounted to “anti-Christian bigotry.”

In an interview after the controversy, Serrano said that he didn’t go out of his way “to be critical of the Church in my work, because I think that I make icons worthy of the Church.” Conservatives at the time disagreed, and latched onto the fact that Serrano received some funding from the National Endowment for the Arts for the work as an excuse to rail against the NEA and even argue for wholesale defunding of the agency. Though the agency survived the “Piss Christ” controversy, the right’s campaign against federal funding for controversial artists did not end with the photograph.

Credit: Andres Serrano

After Serrano, the right shifted their scare tactics to new targets: in 1990, after grant proposals from four artists, Holly Hughes, Karen Finley, Tim Miller and John Fleck, had already been unanimously approved by a peer-review panel, then-NEA chair John Frohnmayer announced that the artists would not be receiving the funds.

The so-called NEA Four charged that they had been denied funding on political grounds: the artists’ work all dealt with socially-charged themes, from sexuality to feminism to gender identity, and after the “Piss Christ” controversy, the agency was on the defensive.

Credit: Dona Ann McAdams

The NEA Four appealed the agency’s decision, winning back their original grant money in lower court rulings and ultimately taking their fight to the Supreme Court. But in 1998, the court ruled in the NEA’s favor, upholding the vague and subjective decency standards the agency used to grant funds. It was a major blow for the Four and for many working artists hoping to receive federal funding, and conservatives didn’t stop there.

Credit: AP Images

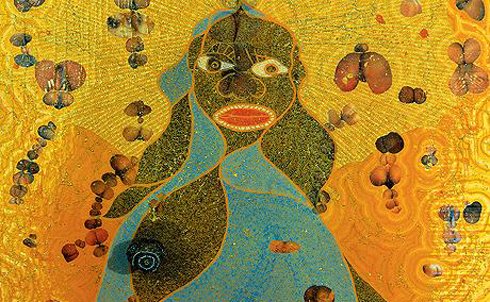

When Chris Ofili’s painting “The Holy Virgin Mary” appeared in a Brooklyn Museum exhibit in 1999, The Nation’s Katha Pollitt called it “a funny, jazzy, rather sweet painting.” Self-appointed guardians of taste and morals didn’t agree: then-New York City Mayor Rudolph Guiliani tried to evict the museum over the exhibit and Camille Paglia called the painting—a Madonna surrounded by porn magazine cutouts, all topped with a dollop of elephant dung—“anti-Catholic.”

Giuliani lost his court case, and as Pollitt points out, his outrage was nothing new: “Aesthetic and political conservatives have been complaining about modern art ever since there was any,” says Pollitt. “It’s not uplifting, or patriotic, or healthy; it’s the work of fakers, perverts and commies… The history of this critique should give us pause—it’s certainly led more often to bonfires than to artworks of lasting interest.”

Most recently, another whitewashing in Los Angeles: the Italian street artist Blu created a massive mural on the wall of MOCA’s Geffen Contemporary building to promote the upcoming “Art in the Streets” exhibit, only to have the museum paint it over less than 24 hours later. MOCA director Jeffrey Deitch deemed the grid of coffins draped with flag-sized dollar bills insensitive, but many others in the art world saw the self-censoring move as an overreaction damaging to the institution’s credibility.

Both the removal of Wojnarowicz’s film from the Smithsonian’s show and the effacement of Blu’s mural “seem like blunders made in haste, perhaps from a sense of urgency brought on by the threat of instantaneous publicity in the Age of Tweeting,” writes Harvey. But with “far more consequential censorship battles being waged on the terms of the brave new digital world—I’m talking WikiLeaks—these clumsy attempts at hierarchical symbolic propriety seem like so many exercises in epistemological nostalgia.”

For more, read Harvey’s article, "The Return of the Culture Wars."