This is the second of three slide shows detailing the lives and legacies of the fifty most influential progressives of the twentieth century. Here, read Peter Dreier’s introduction to the series. Here are the first and third slide shows. Click here to nominate the American progressives you think made the biggest difference in the twentieth century—and the activists, advocates and politicians who are already defining the twenty-first.

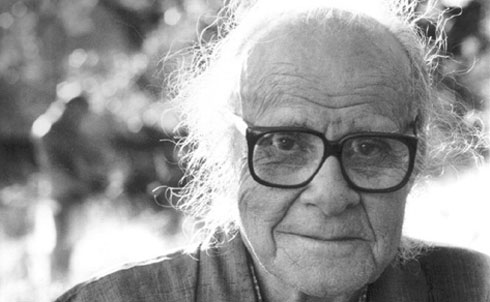

Like Norman Thomas, Muste graduated from Union Theological Seminary. He began his career as a Dutch Reformed Church minister but soon became a Quaker as well as a leading pacifist, antiwar activist, socialist and union organizer. In the early 1920s he led Brookwood Labor College, a training center for union activists, and during the 1930s he led several key sit-downs. From 1940 to 1953 he headed the religious pacifist organization Fellowship of Reconciliation and helped found the Congress on Racial Equality, a militant civil rights group that pioneered the use of civil disobedience and trained many movement activists. In the 1960s he led delegations of pacifists and religious leaders to Saigon and Hanoi to try to end the war in Vietnam.

From The Nation‘s Archives:

Workers’ Education in the United States by A.J. Muste.

Further Reading:

Abraham Went Out: A Biography of A.J. Muste by Jo Ann Robinson.

An immigrant from Lithuania, garment worker in Chicago and lifelong socialist, Hillman led successful strikes and organizing drives, became a union leader and served as president of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers from 1914 to 1946. By 1920 the union had contracts with 85 percent of the nation’s garment manufacturers (representing some 177,000 workers) and had reduced the workweek to forty-four hours. In the 1920s Hillman’s ACWA pioneered “social unionism,” including union-sponsored co-op housing, unemployment insurance for union members and a bank to make loans to members and businesses with union contracts. One of the founders, in 1935, of the CIO (and later its vice president), Hillman became an influential adviser to FDR and Senator Robert Wagner, helping draft laws for workers’ rights. As chair of the CIO’s first political action committee in 1943, he mobilized union voters in election campaigns across the country, which became the model for building an electoral organization among union members.

From The Nation‘s Archives:

Correspondence: RAIC Declares a Dividend by Sidney Hillman.

Further Reading:

Reconstruction of Russia and Task of Labor by Sidney Hillman.

Labor Will Rule: Sidney Hillman and the Rise of American Labor by Steve Fraser.

Credit: AP Images

As FDR’s agriculture secretary (1933–40) and then vice president (1940–44), Wallace played a central role in pushing for progressive New Deal initiatives, especially policies to help struggling farmers. Wallace was a crusading publisher of Wallaces’ Farmer magazine and an Iowa farmer who pioneered the use of high-yield strains of corn. Wallace became increasingly radical and outspoken, and FDR dumped him as vice president in 1944. After serving as editor of The New Republic, he made an unsuccessful run for president in 1948 on the Progressive Party ticket, opposing racial segregation, the cold war and Truman’s tepid support for unions. Wallace was abandoned by many liberals who thought his platform was too radical and who worried that his campaign would take enough votes away from Truman to turn the White House over to the Republicans. He garnered less than 2 percent of the popular vote.

From The Nation‘s Archives:

How to Elect a Progressive Congress by Henry Wallace.

Further Reading:

The Price of Free World Victory, a speech by Henry Wallace.

American Dreamer: A Life of Henry A. Wallace by John C. Culver and John Hyde.

Credit: AP Images

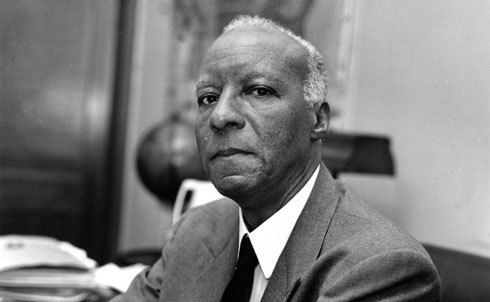

Randolph founded the first African-American labor union, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, in the 1920s. A leading socialist writer, orator and civil rights pioneer, he built bridges between the civil rights and labor movements. He edited the Socialist newspaper The Messenger. In an early editorial, Randolph wrote: “The history of the labor movement in America proves that the employing classes recognize no race lines. They will exploit a White man as readily as a Black man… They will exploit any race or class in order to make profits. The combination of Black and White workers will be a powerful lesson to the capitalists of the solidarity of labor.” Randolph helped bring African-Americans into the labor movement while also criticizing union leaders for excluding blacks. In 1941, as the country was gearing up for war, Randolph threatened to organize a march on Washington to protest blacks’ exclusion from well-paid defense industry jobs. The strategy worked. In June 1941 FDR signed an executive order that called for an end to discrimination in defense plant jobs, America’s first “fair employment practices” reform. Randolph led the 1963 March on Washington, in which more than 250,000 Americans joined together under the slogan “Jobs and Freedom.”

Further Reading:

Excerpts from Randolph’s keynote address to the Policy Conference of the March on Washington Movement in Detroit, Michigan, September 26, 1942.

A. Philip Randolph: A Biographical Portrait by Jervis Anderson.

Credit: AP Images

Reuther rose from the factory floor to help build the United Auto Workers into a major force in the auto industry, the labor movement and the left wing of the Democratic Party. He helped shape the modern labor movement, which created the first mass middle class. He led the 1937 sit-down at the General Motors factory in Flint, Michigan, a major turning point in labor history. After World War II he pushed for a large-scale conversion of the nation’s industrial might to promote peace and full employment. In 1946 he led a 116-day strike against GM, calling for a 30 percent wage increase without an increase in the retail price of cars and challenged GM to “open its books.” In 1948 GM agreed to a historic contract tying wage raises to the general cost-of-living and productivity increases. During his term as UAW president from 1946 until his death in 1970, the union grew to more than 1.5 million members and negotiated model grievance procedures, safety and health provisions, pensions, health benefits and “supplemental unemployment benefits” that lifted union members into the middle class and helped cushion the hardships of economic booms and busts. In the 1960s he led the labor movement’s support for civil rights, was an early opponent of the Vietnam War and an ally of Cesar Chavez’s effort to organize migrant farmworkers. Reuther became president of the CIO in 1952 and helped negotiate the 1955 merger of the AFL and CIO.

From The Nation‘s Archives:

Postscript to Collier’s World War III by Walter Reuther.

Further Reading:

Labor Day Address by Walter Reuther.

Walter Reuther: The Most Dangerous Man in Detroit by Nelson Lichtenstein.

Credit: AP Images

Robeson was perhaps the most all-around talented American of the twentieth century. He was an internationally renowned concert singer, actor, college football star and professional athlete, writer, linguist (he sang in twenty-five languages), scholar, orator, lawyer and activist in the civil rights, union and peace movements. Though he was one of the century’s most famous figures, his name was virtually erased from memory by government persecution during the McCarthy era. The son of a runaway slave, Robeson won a four-year academic scholarship to Rutgers, where he was elected to Phi Beta Kappa and graduated as valedictorian. Despite violence and racism from teammates, he won fifteen varsity letters in sports (baseball, football, basketball and track) and was twice named to the All-American Football Team. He attended Columbia Law School, then took a job with a law firm but quit when a white secretary refused to take dictation from him. He never practiced law again. In London, Robeson earned international acclaim for his lead role in Othello (1944). He starred in many plays and musicals and made eleven films, many with political themes. He promoted African independence, labor unions, friendship between the United States and the Soviet Union, African-American culture, civil liberties and Jewish refugees fleeing Hitler’s Germany. In 1945 he headed an organization that challenged Truman to support an antilynching law. Because of his political views, his performances were constantly harassed. In the late 1940s he was blacklisted. Most of his concerts were canceled, and his passport was revoked in 1950.

Further Reading:

Paul Robeson Speaks: Writings, Speeches, Interviews, 1918–1974.

Paul Robeson: A Biography by Martin B. Duberman.

Credit: Office of War Information Photograph Collection (Library of Congress)

Alinsky is known as the founder of modern community organizing. He taught Americans, especially the urban poor and working class, how to organize to improve conditions in their communities. Trained as a criminologist at the University of Chicago, he realized that criminal behavior was a symptom of poverty and powerlessness. In 1939, to improve living conditions in a Chicago slum near the stockyards, he created the Back of the Yards Neighborhood Council, an “organization of organizations” comprising unions, youth groups, small businesses, block clubs and the Catholic Church. It engaged in pickets, strikes and boycotts to improve neighborhood conditions. His Industrial Areas Foundation trained organizers (including Cesar Chavez) and built grassroots groups in different cities, challenging local political bosses and corporations. He codified his organizing ideas in two books—Reveille for Radicals (1946) and Rules for Radicals (1971)—which influenced several generations of progressive movements and activists.

Further Reading:

Reveille for Radicals and Rules for Radicals by Saul Alinsky.

Let Them Call Me Rebel: Saul Alinsky: His Life and Legacy by Sanford D. Horwitt.

Credit: AP Images

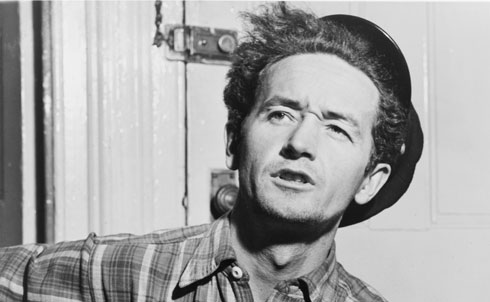

Guthrie, the legendary songwriter and folk singer, is best known for “This Land Is Your Land,” considered America’s alternative national anthem. He traveled from his native Oklahoma across the nation, writing songs about migrant workers, union struggles, government public works projects and the country’s natural beauty, including “I Ain’t Got No Home,” “Tom Joad,” “So Long It’s Been Good to Know Yuh,” “Roll on Columbia,” “Pastures of Plenty,” “Grand Coulee Dam” and “Deportee.” As a member of the Almanac Singers, Guthrie wrote and performed protest songs on behalf of unions and radical organizations. Many of his songs are still recorded by other artists and have influenced generations of performers, including Bob Dylan, Joan Baez and Bruce Springsteen.

Further Reading:

This Land Is Your Land by Woody Guthrie.

Ramblin’ Man: The Life and Times of Woody Guthrie by Ed Cray.

Woody Guthrie: A Life by Joe Klein.

Credit: New York World-Telegram and the Sun Newspaper Photograph Collection (Library of Congress)

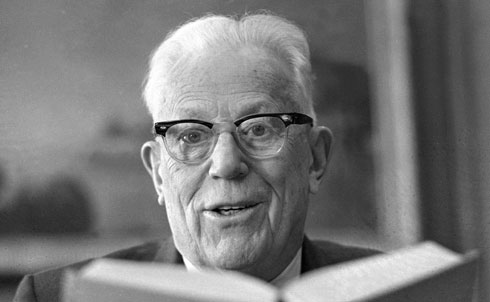

Warren, chief justice from 1953 to 1969, took the Supreme Court in an unprecedented liberal direction. With the help of progressive justices William O. Douglass and William J. Brennan, the Warren Court dramatically expanded civil rights and civil liberties. The Republican Warren used his considerable political skills to guarantee that the 1954 ruling in Brown v. Board of Education was unanimous. In another landmark case, Gideon v. Wainwright (1963), the Warren Court ruled that courts are required to provide attorneys for defendants in criminal cases who cannot afford their own lawyers. In New York Times Co. v. Sullivan (1964), the Court significantly expanded free speech by requiring proof of “actual malice” in libel suits against public figures. The 1965 Griswold v. Connecticut decision established the right to privacy and laid the groundwork for Roe v. Wade (1973). In Miranda v. Arizona (1966), the Court ruled that detained criminal suspects, prior to police questioning, must be informed of their constitutional right to an attorney and against self-incrimination. After serving as Alameda County district attorney, Warren was elected California’s attorney general in 1938 and four years later was elected governor, serving until 1953. In that post he approved the rounding up of Japanese-Americans into detention camps. In 1948 he was the Republican Party’s unsuccessful vice presidential candidate on a ticket with Thomas Dewey. When Eisenhower nominated Warren to the Supreme Court, he thought he was appointing a conservative jurist and later reportedly said that it was the “biggest damn fool mistake” he’d ever made.

Further Reading:

Brown v. Board of Education Ruling, 1954.

Justice for All: Earl Warren and the Nation He Made by Jim Newton.

Chief Justice: A Biography of Earl Warren by Ed Cray.

Credit: AP Images

After graduating from North Carolina’s Shaw University in 1927 as valedictorian, Baker began a lifelong career as a social activist. She served as a mentor to several generations of civil rights activists without drawing much attention to herself. In 1940 she became an organizer for the NAACP, traveling to many small towns and big cities across the South and developing a network of activists. In 1957 Baker moved to Atlanta to help Martin Luther King Jr. organize the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), running a voter registration campaign. After black college students organized a sit-in at the Woolworth’s lunch counter in Greensboro, North Carolina, on February 1, 1960, Baker left the SCLC to help the students spread the sit-in movement. That April she helped them create the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) at a conference at her alma mater.

Further Reading:

Ella Baker and the Black Freedom Movement: A Radical Democratic Vision by Barbara Ransby.

Credit: AP Images

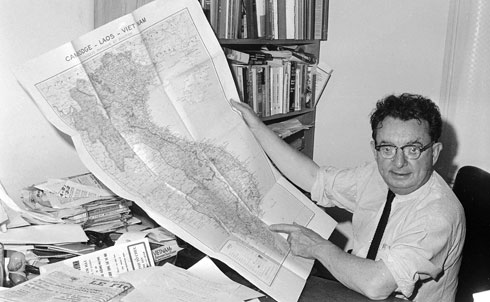

Stone was an investigative journalist whose persistent research uncovered government corruption and wrongdoing. After a career as a reporter for several daily newspapers (including PM, a left-wing newspaper in New York City), he was Washington editor of The Nation from 1940 to 1946. In 1953, at the height of McCarthyism, he started I.F. Stone’s Weekly, keeping the newsletter going until 1971. He was under constant attack during the cold war for his opposition to Senator Joseph McCarthy and for his reporting about the excesses of the FBI under J. Edgar Hoover. Stone was one of a handful of journalists who challenged LBJ’s claim that the North Vietnamese had attacked a US destroyer in the Tonkin Gulf, which had given the president an excuse to go to war in Vietnam. He wrote fifteen books, including, at age 81, The Trial of Socrates (1988). He inspired generations of muckraking reporters.

From The Nation‘s Archives:

For the Jews—Life or Death? by I.F. Stone.

Washington Gestapo by XXX.

Washington Gestapo II by XXX.

Further Reading:

American Radical: The Life and Times of I.F. Stone by D.D. Guttenplan.

Credit: AP Images

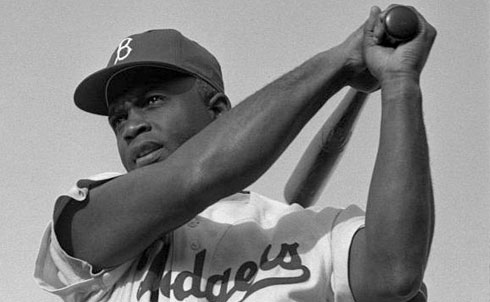

A four-sport athletic star in high school in Pasadena and then at the University of California, Los Angeles, Robinson played in the Negro Leagues before becoming the first African-American to play in the major leagues, in 1947. He endured physical and verbal abuse on and off the field, showing remarkable courage, while helping pave the way for the civil rights movement. Martin Luther King Jr. said to Don Newcombe, Robinson’s teammate, “You, Jackie and Roy [Campanella] will never know how easy you made it for me to do my job.” During World War II Robinson faced a court-martial for refusing to move on a segregated bus outside a military base in Texas. As Rookie of the Year in 1947, Most Valuable Player in 1949 and a six-time All-Star, he led the Brooklyn Dodgers to several pennants. During and after his playing days, he joined picket lines and marches, wrote a newspaper column that attacked racism and raised funds for the NAACP. In testimony before Congress while still a player, he condemned America’s racism but also criticized Paul Robeson’s radicalism, a remark he later said he regretted.

Further Reading:

I Never Had It Made: The Autobiography of Jackie Robinson.

Jackie Robinson: A Biography by Arnold Rampersad.

Baseball’s Great Experiment: Jackie Robinson and His Legacy by Jules Tygiel.

Credit: Look magazine photograph collection (Library of Congress)

Carson was a marine biologist and nature writer who helped inspire the modern environmental movement, especially with her 1962 book, Silent Spring. The book exposed the dangers of synthetic pesticides and led to a nationwide ban on DDT and other pesticides. The movement led to the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency in 1970 and many environmental laws. She laid the groundwork for the growing consciousness of humankind’s stewardship of the planet and a new radical thinking about the environment, most prominently by Barry Commoner, another biologist, whose first books focused on the dangers of nuclear testing and whose The Closing Circle (1971) examined the link between capitalism’s thirst for growth and environmental dangers.

Further Reading:

Silent Spring by Rachel Carson.

Rachel Carson: Witness for Nature by Linda Lear.

Credit: AP Images

Marshall was a leading civil rights lawyer and the first black Supreme Court justice, appointed by LBJ in 1967. As NAACP chief counsel, he led the battle in the courts for civil rights despite repressive conditions and a limited budget. He won his first Supreme Court case, Chambers v. Florida, in 1940, at age 32 and won twenty-nine out of the thirty-two cases he argued before the Court. Many of them were landmark decisions that helped dismantle segregation, including Smith v. Allwright (1944), Shelley v. Kraemer (1948), Sweatt v. Painter (1950) and McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents (1950). His most famous legal victory was Brown v. Board of Education (1954), in which the Court ruled that the “separate but equal” doctrine, established by Plessy v. Ferguson, violated the Constitution. On the Supreme Court he was an outspoken advocate for free speech and civil rights.

Further Reading:

Thurgood Marshall: His Speeches, Writings, Arguments, Opinions, and Reminiscences.

Thurgood Marshall: American Revolutionary by Juan Williams.

Root and Branch: Charles Hamilton Houston, Thurgood Marshall, and the Struggle to End Segregation by Rawn James Jr.

Credit: U.S. News & World Report Magazine Photograph Collection (Library of Congress)

Hay co-founded America’s first major gay rights organization in 1950. Educated at Stanford, Hay became a Communist Party member in Los Angeles in the 1930s and ’40s but left in 1951 because it did not welcome his homosexuality. In December 1950 he organized the first semipublic homosexual discussion group, which soon became the Mattachine Society, known then as a “homophile” group. In 1952 the group led the defense of Dale Jennings, a gay man arrested in an entrapment case. The following year he helped start ONE, a magazine addressing homosexual rights. Hay later was often at odds with younger gay activists who wanted to join the political and cultural mainstream.

Further Reading:

Radically Gay by Harry Hay.

The Trouble With Harry Hay: Founder of the Modern Gay Movement by Stuart Timmons.

Credit: Mark Thompson, from the book "Gay Soul: Finding The Heart of Gay Spirit and Nature."

Peter Dreier’s list of most influential progressives isn’t intended to be complete—we need you to help us fill out the picture! Now that all 50 of the progressives Dreier selected have appeared online, we ask you to nominate the American progressives you think made the biggest difference in the twentieth century—and the activists, advocates and politicians who are already defining the twenty-first. Submit your picks here.

Credit: AP Images