Go here to read Peter Dreier’s introduction to this series detailing the lives and legacies of the fifty most influential progressives of the twentieth century. Go here to see the eleven reader-selected American progressives who Nation readers think made the biggest difference in the twentieth century—and the activists, advocates and politicians who are already defining the twenty-first.

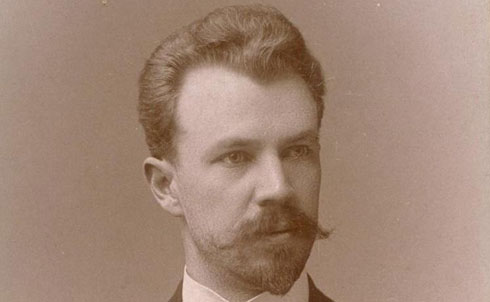

Through his leadership of the labor movement, his five campaigns as a Socialist candidate for president and his spellbinding and brilliant oratory, Debs popularized ideas about civil liberties, workers’ rights, peace and justice and government regulation of big business. In 1893 he organized the nation’s first industrial union, the American Railway Union, to unite all workers within one industry, and he led the Pullman Strike of 1894. He was elected city clerk of Terre Haute and served in the Indiana State Assembly in 1884. In 1900, 1904, 1908, 1912 and 1920, Debs ran for president on the Socialist Party ticket. His speeches and writing influenced popular opinion and the platforms of Democratic Party candidates. His 1920 campaign took place while he was in Atlanta’s federal prison for opposing World War I; he won nearly 1 million votes.

Further Reading:

Statement to the Court by Eugene Debs.

Eugene Debs: Citizen and Socialist by Nick Salvatore.

The Bending Cross: A Biography of Eugene Victor Debs by Ray Ginger.

Credit: National Photo Company Collection (Library of Congress)

Jane Addams pioneered the settlement house movement and was an important Progressive Era urban reformer, the “mother” of American social work, a founder of the NAACP, a champion of women’s suffrage, an antiwar crusader and winner of the 1931 Nobel Peace Prize. Addams carved out a new way for women to become influential in public affairs. In 1889 she and her college friend, Ellen Gates Starr (1859–1940), founded Hull House in Chicago’s immigrant slums, inspired by similar efforts she had seen in England. Initially, the women at Hull House took care of children, nursed the sick, offered kindergarten classes and evening classes for immigrant adults. They then added an art gallery, public kitchen, gym, swimming pool, coffeehouse, cooperative boarding club for girls, book bindery, art studio, music school, drama group, circulating library and employment bureau. Hull House soon became a hub of social activism around labor and immigrant rights, crusades against political corruption, slum housing, unsafe workplaces and child labor. It was the inspiration for other settlement houses in cities across the country.

Further Reading:

Twenty Years at Hull House by Jane Addams.

Jane Adams: Spirit in Action by Louise W. Knight.

The Education of Jane Addams by Victoria Biss Brown.

Credit: AP Images

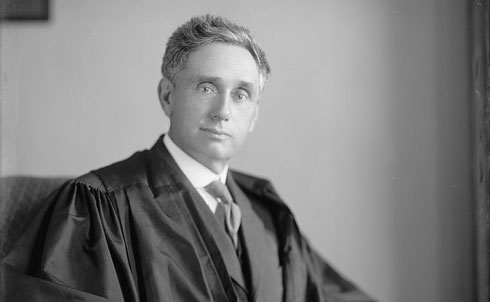

Louis Brandeis was a crusading lawyer and Supreme Court justice. Appointed by Woodrow Wilson in 1916, he served until 1939. His writings and activism changed American attitudes and law about the need to restrain corporate power, outlined in his book Other People’s Money and How the Bankers Use It (1914). As a “people’s lawyer” in Boston, he fought railroad monopolies, defended labor laws and helped create policies to address poverty—an approach that is now called public interest law. He pioneered the use of expert testimony (called the Brandeis Brief) in court cases, paving the way for an approach to the law that relied on empirical evidence. In 1908 he represented the state of Oregon in Muller v. Oregon before the Supreme Court. The issue was whether a state could limit the hours that female workers could work, which employers argued was an infringement on the “freedom of contract” between employers and their employees. His legal argument was relatively short, but he included more than 100 pages of documentation, including reports from social workers, doctors, factory inspectors and other experts, which showed that working long hours destroyed women’s health and well-being. Brandeis won the case and changed the field of litigation.

Further Reading:

Other People’s Money—And How the Bankers Use It by Louis Brandeis.

Louis D. Brandeis: A Life by Melvin I. Urofsky.

Louis D. Brandeis: Justice for the People by Philippa Strum.

Credit: Harris & Ewing Collection (Library of Congress)

Florence Kelley was a leading organizer against sweatshops and an advocate for children’s rights, the minimum wage and the eight-hour workday. Part of the first generation of women to attend college, she joined the Intercollegiate Socialist Society, was active in women’s suffrage and was a founder of the NAACP. She worked at Hull House from 1891 to 1899 and the Henry Street Settlement in New York City from 1899 to 1926. In 1893 Governor John Altgeld appointed her Illinois’s first chief factory inspector, a position she used to expose abusive working conditions, especially for children. She successfully lobbied for the creation of the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics so that reformers would have adequate information about the condition of workers. In 1908 she gathered sociological and medical evidence for Muller v. Oregon and in 1917 gathered similar information for Bunting v. Oregon to make the case for an eight-hour workday.

From The Nation‘s Archives:

Shall Women Be Equal Before the Law? by Florence Kelley and Elsie Hill.

Further Reading:

Modern Industry: In Relation to the Family, Health, Education and Morality by Florence Kelley.

Florence Kelley and the Nation’s Work by Kathryn Kish Sklar.

Credit: Library of Congress

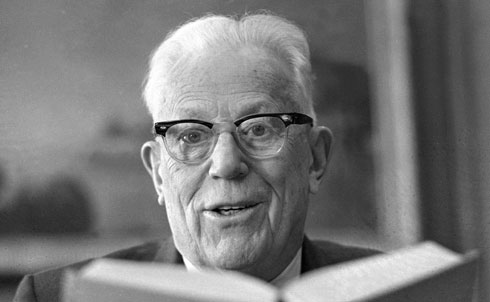

A philosopher, psychologist and education reformer, Dewey was an engaged activist, a prolific writer for popular magazines and the leading exemplar of American pragmatism. He founded the “laboratory school” at the University of Chicago to put his ideas about progressive education into practice. His ideas about “experiential learning” influenced several generations of educators. An early supporter of teachers’ unions and academic freedom, he spoke out and organized against efforts to restrict freedom of ideas, helped found the NAACP and supported women’s suffrage.

From The Nation‘s Archives:

The Future of Radical Political Action by John Dewey.

Further Reading:

Democracy and Education by John Dewey.

John Dewey and American Democracy by Robert B. Westbrook.

Uncertain Victory: Social Democracy and Progressivism in European and American Thought, 1870-1920 by James T. Kloppenberg.

Credit: AP Images

As a writer and editor for McClure’s magazine and later for The American Magazine, he (along with colleagues Ida Tarbell and Ray Stannard Baker) was an influential practitioner of “muckraking” journalism. In The Shame of the Cities (1904), he exposed corruption by local governments, which took advantage of poor immigrants and colluded with business power brokers. After visiting the Soviet Union in 1919, he became an enthusiastic supporter of the Russian Revolution, famously proclaiming, “I have been over into the future, and it works.” He later soured on Soviet-style communism.

From The Nation‘s Archives:

Further Reading:

The Shame of the Cities by Lincoln Steffens.

Lincoln Steffens: A Biography by Justin Kaplan.

Credit: The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley.

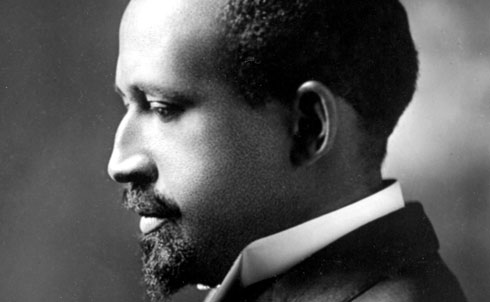

Du Bois was a civil rights activist, sociologist, historian, polemicist and editor. He was the first African-American to receive a Ph.D. from Harvard and a founder of the NAACP. In his studies and books he challenged America’s ideas about race and helped lead the early crusade for civil rights. Du Bois’s intellectual and political battles with Booker T. Washington shaped the ongoing debate about the nature of racism and the struggle for racial justice, summarized in his book The Souls of Black Folk (1903), in which he described blacks’ “double consciousness” and famously predicted, “The problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color line.” From 1910 to 1934 he served as editor of The Crisis, the NAACP’s monthly magazine, which became a highly visible and often controversial forum for criticism of white racism, lynching and segregation, and for information about the status of black Americans. It gave exposure to many young African-American writers, poets and agitators. Du Bois was a Socialist, although he often disagreed with the party, particularly on matters of race. His writings had enormous influence on civil rights activists and on the burgeoning fields of black history and black studies.

From The Nation‘s Archives:

The Hosts of Black Labor by W.E.B. Du Bois.

Further Reading:

The Souls of Black Folk by W.E.B. Du Bois.

W.E.B. Du Bois, 1868-1919: Biography of a Race by David L. Lewis.

W.E.B. Bu Bois, 1919-1963: The Fight for Equality and the American Century by David L. Lewis.

Credit: Addison N. Scurlock, National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

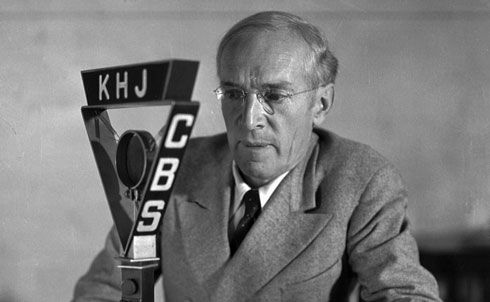

A Pulitzer Prize–winning author, Sinclair wrote ninety books, most of which were novels that exposed social injustice or studies of powerful institutions (including religion, the press and oil companies). His 1906 novel The Jungle, which vividly described awful conditions in the meatpacking industry, caused a public uproar that led to passage of the Pure Food and Drug Act and the Meat Inspection Act. In 1934, in the depths of the Depression, he left the Socialist Party and won the Democratic nomination for governor of California on a platform to “end poverty in California.” The state’s powerful agricultural, oil and media industries mounted an expensive negative campaign to attack Sinclair and help elect his Republican opponent. Sinclair lost, but his campaign mobilized millions of voters, helped push FDR to the left and changed California politics for the next several decades.

From The Nation‘s Archives:

My Private Utopia, by Upton Sinclair.

Further Reading:

The Jungle by Upton Sinclair.

Radical Innocent: Upton Sinclair by Anthony Arthur.

Upton Sinclair and the Other American Century by Kevin Mattson.

Credit: AP Images

Sanger worked as a nurse among poor women on New York City’s Lower East Side and became an advocate for women’s health. In 1912 she gave up nursing and dedicated herself to the distribution of information about birth control (a term she’s credited with inventing), risking imprisonment for violating the Comstock Act, which forbade distribution of birth control devices or information. She wrote articles on health for the Socialist Party paper The Call and wrote several books, including What Every Girl Should Know (1916) and What Every Mother Should Know (1916). In 1921 she founded the American Birth Control League, which eventually became Planned Parenthood. In 1916 she set up the first birth control clinic in the United States, and the following year she was arrested for “creating a public nuisance.” Her activism helped change public opinion and led to changes in laws giving doctors the right to give birth control advice (and later, birth control devices) to patients.

From The Nation‘s Archives:

The Pope’s Position on Birth Control by Margaret Sanger.

Further Reading:

What Every Girl Should Know and What Every Mother Should Know by Margaret Sanger.

Birth Control In America: The Career of Margaret Sanger by David M. Kennedy.

Woman of Valor: Margaret Sanger and the Birth Control Movement in America by Ellen Chesler.

Credit: AP Images

Gilman was a pathbreaking feminist, humanist and socialist, whose lectures and writing challenged the dominant ideas about women’s role in society and helped shape the movement for women’s suffrage and rights. After attending her first suffrage convention in 1886, she began writing a column on suffrage for The People. She addressed the 1896 conference of the National American Woman Suffrage Association in Washington and testified for suffrage before Congress. She called women “subcitizens” and their disenfranchisement “arbitrary, unjust, unwise.” Her semiautobiographical short story “The Yellow Wallpaper” (1892) described a woman who suffers a mental breakdown resulting from a “rest cure”—prescribed by her physician husband—of complete long-term isolation in her bedroom. In many books, including Women and Economics (1898), The Home (1903), Human Work (1904) and The Man-Made World (1911), she argued that women would be equal to men only when they were economically independent, and she encouraged women to work outside the home and for men and women to share house-work. She believed that housekeeping, cooking and childcare should be professionalized. Girls and boys, she thought, should be raised with the same clothes, toys and expectations. Gilman’s efforts complemented the activism of feminists like Alice Stokes Paul (1885–1977), who organized pickets, parades and hunger strikes to win passage of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920.

From The Nation‘s Archives:

Birth Control, Religion and the Unfit by Charlotte Perkins Gilman.

Further Reading:

Women and Economics and Herland by Charlotte Perkins Gilman.

Charlotte Perkins Gilman: A Biography by Cynthia J. Davis.

A pacifist and social activist, Baldwin was a founder, in 1917, of the American Civil Liberties Union (originally the National Civil Liberties Bureau), created to defend the rights of antiwar conscientious objectors, and served as its executive director until 1950. Under his leadership the ACLU litigated many landmark cases, including the Scopes Trial, the Sacco and Vanzetti murder trial and the challenge to the ban on James Joyce’s Ulysses.

From The Nation‘s Archive:

Editorial on General Douglas MacArthur by Roger Baldwin.

Further Reading:

Liberty Under the Soviets and A New Slavery: Forced Labor, the Communist Betrayal of Human Rights by Roger Baldwin.

Roger Nash Baldwin and the American Civil Liberties Union by Robert C. Cotrell.

Credit: Princeton University Library

Perkins was labor secretary for the first twelve years of Franklin Roosevelt’s presidency and the first woman to hold a cabinet post. Within FDR’s inner circle she advocated for Social Security, the minimum wage, workers’ right to unionize and other New Deal economic reforms. Inspired by Jacob Riis’s exposé of New York’s slums, How the Other Half Lives, and by reformer Florence Kelley, she joined the settlement house movement and worked for the New York Consumers’ League, lobbying the state legislature to limit the workweek for women and children to fifty-four hours. She marched in suffrage parades and gave street-corner speeches in favor of women’s suffrage. She joined the Socialist Party but soon switched to the Democratic Party. In 1918 New York Governor Al Smith appointed her to the state’s Industrial Commission, and in 1929 Governor Franklin Roosevelt appointed her the state’s industrial commissioner. She expanded factory investigations, reduced the workweek for women to forty-eight hours and championed minimum wage and unemployment insurance laws, all ideas she took to Washington when she joined FDR’s cabinet.

From The Nation‘s Archives:

Rise of a Labor Leader by Frances Perkins.

Further Reading:

Social Insurance for the US, a radio address by Frances Perkins.

The Woman Behind the New Deal: The Life and Legacy of Frances Perkins by Kirstin Downey.

Credit: AP Images

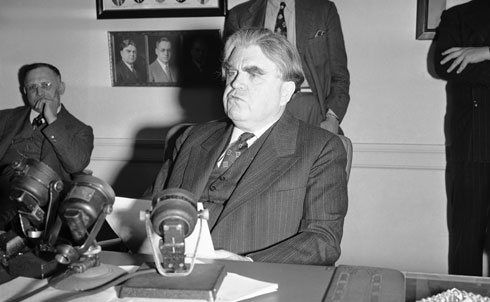

Joining his father as a miner at 16, Lewis became active in the United Mine Workers of America, working his way up to president, a post he held from 1920 to 1960. Under Lewis the UMWA committed money and staff to organizing drives in the rubber, auto and steel industries, helping to create a national wave of industrial unionism. In 1938 Lewis was elected president of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) at its founding convention and became a major public face of the nation’s growing and increasingly militant labor movement. In 1948 the UMWA won a historic agreement with coal companies establishing medical and pension benefits for miners, financed in part by a royalty on every ton of coal mined.

From The Nation‘s Archives:

An Inter-Union Labor Struggle by John L. Lewis.

Further Reading:

Labor and the Nation by John L. Lewis.

John L. Lewis: A Biography by Melvyn Dubofsky and Warren Van Tine.

Credit: AP Images

Roosevelt was born to privilege but became one of the most visible social activists of her generation. She used her prominence as first lady to advocate for reform, giving visibility to movements for workers’ rights, women’s rights and civil rights and pushing FDR and his advisers to support progressive legislation. She held press conferences and voiced her opinions in radio broadcasts and a regular newspaper col-umn. She visited coal mines, slums and schools to draw attention to the plight of the disadvantaged and to lobby for reform laws. Her resignation from the Daughters of the American Revolution—to protest its ban on black singer Marian Anderson performing at Constitution Hall—made a controversial and powerful statement for racial justice. In 1948, as a delegate to the United Nations, she helped draft the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which affirmed equality for all people regardless of race, creed or color.

From The Nation‘s Archives:

Fear is the Enemy by Eleanor Roosevelt.

Further Reading:

The Autobiography of Eleanor Roosevelt.

Eleanor Roosevelt, Volume I: 1884-1933 by Blanche Wiesen Cook.

Eleanor Roosevelt, Volume II: The Defining Years, 1933-1938 by Blanche Wiesen Cook.

Credit: United Nations

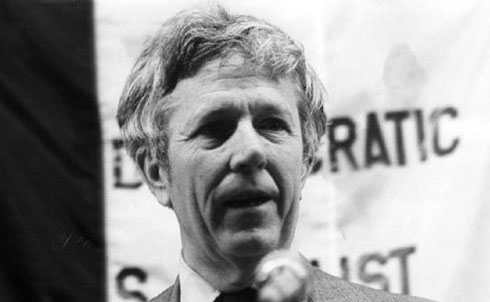

Thomas was America’s most visible socialist from the 1930s through the ’50s. Ordained a Presbyterian minister in 1911, he became a crusader for the “social gospel” as the leader of several churches and head of a settlement house in Harlem. His pacifism and opposition to World War I led him to join the Socialist Party. After writing about reform issues for Christian publications, he joined The Nation as associate editor. In 1922 he became co-director of the League for Industrial Democracy and was a founder of the National Civil Liberties Bureau. He ran for governor, mayor, State Senate and City Council on the Socialist Party ticket. Starting in 1928 he ran for president six times, gaining a public voice as an articulate national “conscience” and spokesman for democratic socialism. Thomas was one of the few public figures to oppose the internment of Japanese-Americans. He helped start the racially integrated Southern Farmers Tenants Union, campaigned for labor rights, birth control and allowing Jewish victims of Nazism to enter the United States. At his eightieth birthday celebration, in 1964, he received plaudits from Martin Luther King Jr., Chief Justice Earl Warren and Vice President-elect Hubert Humphrey. An early critic of the Vietnam War, he gave a famous antiwar speech in 1968, proclaiming, “I come to cleanse the American flag, not burn it.”

From The Nation‘s Archives:

The Pacifist’s Dilemma by Norman Thomas.

Further Reading:

Is Conscience A Crime? and Socialism Re-examined by Norman Thomas.

Norman Thomas: The Last Idealist by W.A. Swanberg.

Credit: AP Images

Like Norman Thomas, Muste graduated from Union Theological Seminary. He began his career as a Dutch Reformed Church minister but soon became a Quaker as well as a leading pacifist, antiwar activist, socialist and union organizer. In the early 1920s he led Brookwood Labor College, a training center for union activists, and during the 1930s he led several key sit-downs. From 1940 to 1953 he headed the religious pacifist organization Fellowship of Reconciliation and helped found the Congress on Racial Equality, a militant civil rights group that pioneered the use of civil disobedience and trained many movement activists. In the 1960s he led delegations of pacifists and religious leaders to Saigon and Hanoi to try to end the war in Vietnam.

From The Nation‘s Archives:

Workers’ Education in the United States by A.J. Muste.

Further Reading:

Abraham Went Out: A Biography of A.J. Muste by Jo Ann Robinson.

An immigrant from Lithuania, garment worker in Chicago and lifelong socialist, Hillman led successful strikes and organizing drives, became a union leader and served as president of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers from 1914 to 1946. By 1920 the union had contracts with 85 percent of the nation’s garment manufacturers (representing some 177,000 workers) and had reduced the workweek to forty-four hours. In the 1920s Hillman’s ACWA pioneered “social unionism,” including union-sponsored co-op housing, unemployment insurance for union members and a bank to make loans to members and businesses with union contracts. One of the founders, in 1935, of the CIO (and later its vice president), Hillman became an influential adviser to FDR and Senator Robert Wagner, helping draft laws for workers’ rights. As chair of the CIO’s first political action committee in 1943, he mobilized union voters in election campaigns across the country, which became the model for building an electoral organization among union members.

From The Nation‘s Archives:

Correspondence: RAIC Declares a Dividend by Sidney Hillman.

Further Reading:

Reconstruction of Russia and Task of Labor by Sidney Hillman.

Labor Will Rule: Sidney Hillman and the Rise of American Labor by Steve Fraser.

Credit: AP Images

As FDR’s agriculture secretary (1933–40) and then vice president (1940–44), Wallace played a central role in pushing for progressive New Deal initiatives, especially policies to help struggling farmers. Wallace was a crusading publisher of Wallaces’ Farmer magazine and an Iowa farmer who pioneered the use of high-yield strains of corn. Wallace became increasingly radical and outspoken, and FDR dumped him as vice president in 1944. After serving as editor of The New Republic, he made an unsuccessful run for president in 1948 on the Progressive Party ticket, opposing racial segregation, the cold war and Truman’s tepid support for unions. Wallace was abandoned by many liberals who thought his platform was too radical and who worried that his campaign would take enough votes away from Truman to turn the White House over to the Republicans. He garnered less than 2 percent of the popular vote.

From The Nation‘s Archives:

How to Elect a Progressive Congress by Henry Wallace.

Further Reading:

The Price of Free World Victory, a speech by Henry Wallace.

American Dreamer: A Life of Henry A. Wallace by John C. Culver and John Hyde.

Credit: AP Images

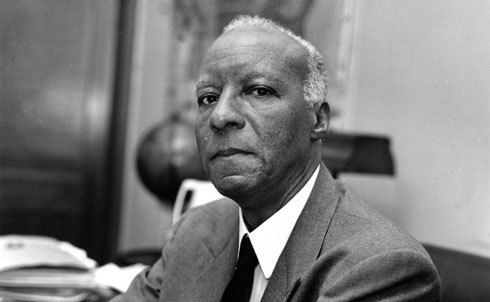

Randolph founded the first African-American labor union, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, in the 1920s. A leading socialist writer, orator and civil rights pioneer, he built bridges between the civil rights and labor movements. He edited the Socialist newspaper The Messenger. In an early editorial, Randolph wrote: “The history of the labor movement in America proves that the employing classes recognize no race lines. They will exploit a White man as readily as a Black man… They will exploit any race or class in order to make profits. The combination of Black and White workers will be a powerful lesson to the capitalists of the solidarity of labor.” Randolph helped bring African-Americans into the labor movement while also criticizing union leaders for excluding blacks. In 1941, as the country was gearing up for war, Randolph threatened to organize a march on Washington to protest blacks’ exclusion from well-paid defense industry jobs. The strategy worked. In June 1941 FDR signed an executive order that called for an end to discrimination in defense plant jobs, America’s first “fair employment practices” reform. Randolph led the 1963 March on Washington, in which more than 250,000 Americans joined together under the slogan “Jobs and Freedom.”

Further Reading:

Excerpts from Randolph’s keynote address to the Policy Conference of the March on Washington Movement in Detroit, Michigan, September 26, 1942.

A. Philip Randolph: A Biographical Portrait by Jervis Anderson.

Credit: AP Images

Reuther rose from the factory floor to help build the United Auto Workers into a major force in the auto industry, the labor movement and the left wing of the Democratic Party. He helped shape the modern labor movement, which created the first mass middle class. He led the 1937 sit-down at the General Motors factory in Flint, Michigan, a major turning point in labor history. After World War II he pushed for a large-scale conversion of the nation’s industrial might to promote peace and full employment. In 1946 he led a 116-day strike against GM, calling for a 30 percent wage increase without an increase in the retail price of cars and challenged GM to “open its books.” In 1948 GM agreed to a historic contract tying wage raises to the general cost-of-living and productivity increases. During his term as UAW president from 1946 until his death in 1970, the union grew to more than 1.5 million members and negotiated model grievance procedures, safety and health provisions, pensions, health benefits and “supplemental unemployment benefits” that lifted union members into the middle class and helped cushion the hardships of economic booms and busts. In the 1960s he led the labor movement’s support for civil rights, was an early opponent of the Vietnam War and an ally of Cesar Chavez’s effort to organize migrant farmworkers. Reuther became president of the CIO in 1952 and helped negotiate the 1955 merger of the AFL and CIO.

From The Nation‘s Archives:

Postscript to Collier’s World War III by Walter Reuther.

Further Reading:

Labor Day Address by Walter Reuther.

Walter Reuther: The Most Dangerous Man in Detroit by Nelson Lichtenstein.

Credit: AP Images

Robeson was perhaps the most all-around talented American of the twentieth century. He was an internationally renowned concert singer, actor, college football star and professional athlete, writer, linguist (he sang in twenty-five languages), scholar, orator, lawyer and activist in the civil rights, union and peace movements. Though he was one of the century’s most famous figures, his name was virtually erased from memory by government persecution during the McCarthy era. The son of a runaway slave, Robeson won a four-year academic scholarship to Rutgers, where he was elected to Phi Beta Kappa and graduated as valedictorian. Despite violence and racism from teammates, he won fifteen varsity letters in sports (baseball, football, basketball and track) and was twice named to the All-American Football Team. He attended Columbia Law School, then took a job with a law firm but quit when a white secretary refused to take dictation from him. He never practiced law again. In London, Robeson earned international acclaim for his lead role in Othello (1944). He starred in many plays and musicals and made eleven films, many with political themes. He promoted African independence, labor unions, friendship between the United States and the Soviet Union, African-American culture, civil liberties and Jewish refugees fleeing Hitler’s Germany. In 1945 he headed an organization that challenged Truman to support an antilynching law. Because of his political views, his performances were constantly harassed. In the late 1940s he was blacklisted. Most of his concerts were canceled, and his passport was revoked in 1950.

Further Reading:

Paul Robeson Speaks: Writings, Speeches, Interviews, 1918–1974.

Paul Robeson: A Biography by Martin B. Duberman.

Credit: Office of War Information Photograph Collection (Library of Congress)

Alinsky is known as the founder of modern community organizing. He taught Americans, especially the urban poor and working class, how to organize to improve conditions in their communities. Trained as a criminologist at the University of Chicago, he realized that criminal behavior was a symptom of poverty and powerlessness. In 1939, to improve living conditions in a Chicago slum near the stockyards, he created the Back of the Yards Neighborhood Council, an “organization of organizations” comprising unions, youth groups, small businesses, block clubs and the Catholic Church. It engaged in pickets, strikes and boycotts to improve neighborhood conditions. His Industrial Areas Foundation trained organizers (including Cesar Chavez) and built grassroots groups in different cities, challenging local political bosses and corporations. He codified his organizing ideas in two books—Reveille for Radicals (1946) and Rules for Radicals (1971)—which influenced several generations of progressive movements and activists.

Further Reading:

Reveille for Radicals and Rules for Radicals by Saul Alinsky.

Let Them Call Me Rebel: Saul Alinsky: His Life and Legacy by Sanford D. Horwitt.

Credit: AP Images

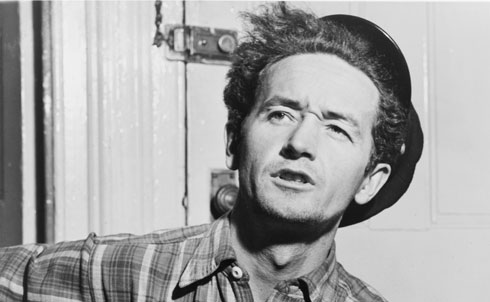

Guthrie, the legendary songwriter and folk singer, is best known for “This Land Is Your Land,” considered America’s alternative national anthem. He traveled from his native Oklahoma across the nation, writing songs about migrant workers, union struggles, government public works projects and the country’s natural beauty, including “I Ain’t Got No Home,” “Tom Joad,” “So Long It’s Been Good to Know Yuh,” “Roll on Columbia,” “Pastures of Plenty,” “Grand Coulee Dam” and “Deportee.” As a member of the Almanac Singers, Guthrie wrote and performed protest songs on behalf of unions and radical organizations. Many of his songs are still recorded by other artists and have influenced generations of performers, including Bob Dylan, Joan Baez and Bruce Springsteen.

Further Reading:

This Land Is Your Land by Woody Guthrie.

Ramblin’ Man: The Life and Times of Woody Guthrie by Ed Cray.

Woody Guthrie: A Life by Joe Klein.

Credit: New York World-Telegram and the Sun Newspaper Photograph Collection (Library of Congress)

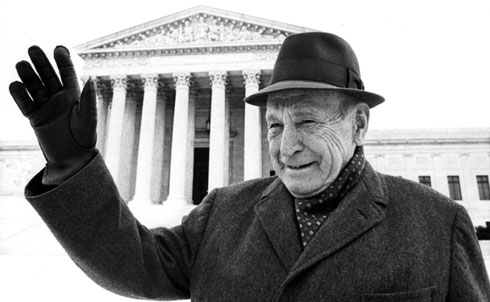

Warren, chief justice from 1953 to 1969, took the Supreme Court in an unprecedented liberal direction. With the help of progressive justices William O. Douglass and William J. Brennan, the Warren Court dramatically expanded civil rights and civil liberties. The Republican Warren used his considerable political skills to guarantee that the 1954 ruling in Brown v. Board of Education was unanimous. In another landmark case, Gideon v. Wainwright (1963), the Warren Court ruled that courts are required to provide attorneys for defendants in criminal cases who cannot afford their own lawyers. In New York Times Co. v. Sullivan (1964), the Court significantly expanded free speech by requiring proof of “actual malice” in libel suits against public figures. The 1965 Griswold v. Connecticut decision established the right to privacy and laid the groundwork for Roe v. Wade (1973). In Miranda v. Arizona (1966), the Court ruled that detained criminal suspects, prior to police questioning, must be informed of their constitutional right to an attorney and against self-incrimination. After serving as Alameda County district attorney, Warren was elected California’s attorney general in 1938 and four years later was elected governor, serving until 1953. In that post he approved the rounding up of Japanese-Americans into detention camps. In 1948 he was the Republican Party’s unsuccessful vice presidential candidate on a ticket with Thomas Dewey. When Eisenhower nominated Warren to the Supreme Court, he thought he was appointing a conservative jurist and later reportedly said that it was the “biggest damn fool mistake” he’d ever made.

Further Reading:

Brown v. Board of Education Ruling, 1954.

Justice for All: Earl Warren and the Nation He Made by Jim Newton.

Chief Justice: A Biography of Earl Warren by Ed Cray.

Credit: AP Images

After graduating from North Carolina’s Shaw University in 1927 as valedictorian, Baker began a lifelong career as a social activist. She served as a mentor to several generations of civil rights activists without drawing much attention to herself. In 1940 she became an organizer for the NAACP, traveling to many small towns and big cities across the South and developing a network of activists. In 1957 Baker moved to Atlanta to help Martin Luther King Jr. organize the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), running a voter registration campaign. After black college students organized a sit-in at the Woolworth’s lunch counter in Greensboro, North Carolina, on February 1, 1960, Baker left the SCLC to help the students spread the sit-in movement. That April she helped them create the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) at a conference at her alma mater.

Further Reading:

Ella Baker and the Black Freedom Movement: A Radical Democratic Vision by Barbara Ransby.

Credit: AP Images

Stone was an investigative journalist whose persistent research uncovered government corruption and wrongdoing. After a career as a reporter for several daily newspapers (including PM, a left-wing newspaper in New York City), he was Washington editor of The Nation from 1940 to 1946. In 1953, at the height of McCarthyism, he started I.F. Stone’s Weekly, keeping the newsletter going until 1971. He was under constant attack during the cold war for his opposition to Senator Joseph McCarthy and for his reporting about the excesses of the FBI under J. Edgar Hoover. Stone was one of a handful of journalists who challenged LBJ’s claim that the North Vietnamese had attacked a US destroyer in the Tonkin Gulf, which had given the president an excuse to go to war in Vietnam. He wrote fifteen books, including, at age 81, The Trial of Socrates (1988). He inspired generations of muckraking reporters.

From The Nation‘s Archives:

For the Jews—Life or Death? by I.F. Stone.

Washington Gestapo by XXX.

Washington Gestapo II by XXX.

Further Reading:

American Radical: The Life and Times of I.F. Stone by D.D. Guttenplan.

Credit: AP Images

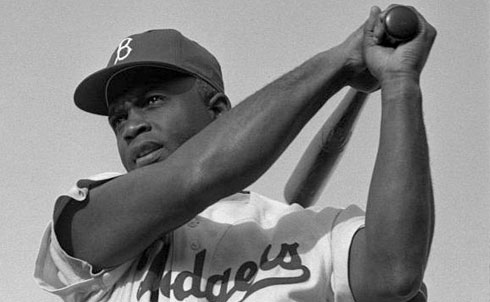

A four-sport athletic star in high school in Pasadena and then at the University of California, Los Angeles, Robinson played in the Negro Leagues before becoming the first African-American to play in the major leagues, in 1947. He endured physical and verbal abuse on and off the field, showing remarkable courage, while helping pave the way for the civil rights movement. Martin Luther King Jr. said to Don Newcombe, Robinson’s teammate, “You, Jackie and Roy [Campanella] will never know how easy you made it for me to do my job.” During World War II Robinson faced a court-martial for refusing to move on a segregated bus outside a military base in Texas. As Rookie of the Year in 1947, Most Valuable Player in 1949 and a six-time All-Star, he led the Brooklyn Dodgers to several pennants. During and after his playing days, he joined picket lines and marches, wrote a newspaper column that attacked racism and raised funds for the NAACP. In testimony before Congress while still a player, he condemned America’s racism but also criticized Paul Robeson’s radicalism, a remark he later said he regretted.

Further Reading:

I Never Had It Made: The Autobiography of Jackie Robinson.

Jackie Robinson: A Biography by Arnold Rampersad.

Baseball’s Great Experiment: Jackie Robinson and His Legacy by Jules Tygiel.

Credit: Look magazine photograph collection (Library of Congress)

Carson was a marine biologist and nature writer who helped inspire the modern environmental movement, especially with her 1962 book, Silent Spring. The book exposed the dangers of synthetic pesticides and led to a nationwide ban on DDT and other pesticides. The movement led to the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency in 1970 and many environmental laws. She laid the groundwork for the growing consciousness of humankind’s stewardship of the planet and a new radical thinking about the environment, most prominently by Barry Commoner, another biologist, whose first books focused on the dangers of nuclear testing and whose The Closing Circle (1971) examined the link between capitalism’s thirst for growth and environmental dangers.

Further Reading:

Silent Spring by Rachel Carson.

Rachel Carson: Witness for Nature by Linda Lear.

Credit: AP Images

Marshall was a leading civil rights lawyer and the first black Supreme Court justice, appointed by LBJ in 1967. As NAACP chief counsel, he led the battle in the courts for civil rights despite repressive conditions and a limited budget. He won his first Supreme Court case, Chambers v. Florida, in 1940, at age 32 and won twenty-nine out of the thirty-two cases he argued before the Court. Many of them were landmark decisions that helped dismantle segregation, including Smith v. Allwright (1944), Shelley v. Kraemer (1948), Sweatt v. Painter (1950) and McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents (1950). His most famous legal victory was Brown v. Board of Education (1954), in which the Court ruled that the “separate but equal” doctrine, established by Plessy v. Ferguson, violated the Constitution. On the Supreme Court he was an outspoken advocate for free speech and civil rights.

Further Reading:

Thurgood Marshall: His Speeches, Writings, Arguments, Opinions, and Reminiscences.

Thurgood Marshall: American Revolutionary by Juan Williams.

Root and Branch: Charles Hamilton Houston, Thurgood Marshall, and the Struggle to End Segregation by Rawn James Jr.

Credit: U.S. News & World Report Magazine Photograph Collection (Library of Congress)

Hay co-founded America’s first major gay rights organization in 1950. Educated at Stanford, Hay became a Communist Party member in Los Angeles in the 1930s and ’40s but left in 1951 because it did not welcome his homosexuality. In December 1950 he organized the first semipublic homosexual discussion group, which soon became the Mattachine Society, known then as a “homophile” group. In 1952 the group led the defense of Dale Jennings, a gay man arrested in an entrapment case. The following year he helped start ONE, a magazine addressing homosexual rights. Hay later was often at odds with younger gay activists who wanted to join the political and cultural mainstream.

Further Reading:

Radically Gay by Harry Hay.

The Trouble With Harry Hay: Founder of the Modern Gay Movement by Stuart Timmons.

Credit: Mark Thompson, from the book "Gay Soul: Finding The Heart of Gay Spirit and Nature."

King helped change America’s conscience, not only about civil rights but also about economic justice, poverty and war. As an inexperienced young pastor in Montgomery, Alabama, King was reluctantly thrust into the leadership of the bus boycott. During the 382-day boycott, King was arrested and abused and his home was bombed, but he emerged as a national figure and honed his leadership skills. In 1957 he helped launch the SCLC to spread the civil rights crusade to other cities. He helped lead local campaigns in Selma, Birmingham and other cities, and sought to keep the fractious civil rights movement together, including the NAACP, Urban League, SNCC, CORE and SCLC. Between 1957 and 1968 King traveled more than 6 million miles, spoke more than 2,500 times and was arrested at least twenty times while preaching the gospel of nonviolence. Today we view King as something of a saint; his birthday is a national holiday and his name adorns schools and street signs. But in his day the establishment considered King a dangerous troublemaker. He was harassed by the FBI and vilified in the media. The struggle for civil rights radicalized him into a fighter for economic and social justice. During the 1960s King became increasingly committed to building bridges between the civil rights and labor movements. He was in Memphis in 1968 to support striking sanitation workers when he was assassinated. In 1964, at 35, King was the youngest man to have received the Nobel Peace Prize. Some civil rights activists worried that his opposition to the Vietnam War, announced in 1967, would create a backlash against civil rights, but instead it helped turned the tide of public opinion against the war.

From The Nation‘s Archives:

Let Justice Roll Down by Martin Luther King Jr.

Further Reading:

Why We Can’t Wait by Martin Luther King Jr.

Bearing the Cross: Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference by David J. Garrow.

Parting the Waters: America in the King Years 1954-63 by Taylor Branch.

Credit: AP Images

Rustin was one of the nation’s most talented organizers, typically working behind the scenes, as an aide to Muste, Randolph and King, in large part because they feared that his homosexuality would stigmatize their causes and organizations. Randolph appointed him to lead the youth wing of the 1941 march on Washington movement. Rustin was upset when Randolph called off the march after FDR issued an executive order banning racial discrimination in the defense industries. Rustin then began a series of organizing jobs in the peace movement, honing his skills with the Fellowship of Reconciliation, the American Friends Service Committee, the Socialist Party and the War Resisters League. In 1947 he began organizing a series of nonviolent acts of civil disobedience in the South and border states to provoke a challenge to Jim Crow practices in interstate transportation. Between 1947 and 1952 Rustin traveled to India and Africa to learn more about nonviolence and the Gandhian independence movement. Rustin spent time in Montgomery and Birmingham advising King about nonviolent tactics. Coming full circle, Randolph named him chief organizer of the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, diplomatically bringing together fractious civil rights leaders and organizations.

From The Nation‘s Archives:

Letter to the Editor: Human Detente by Bayard Rustin.

Further Reading:

From Protest to Politics: The Future of the Civil Rights Movement by Bayard Rustin.

Lost Prophet: The Life and Times of Bayard Rustin by John D’Emilio.

Bayard Rustin: Troubles I’ve Seen by Jervis Anderson.

Credit: New York World-Telegram and the Sun Newspaper Photograph Collection (Library of Congress)

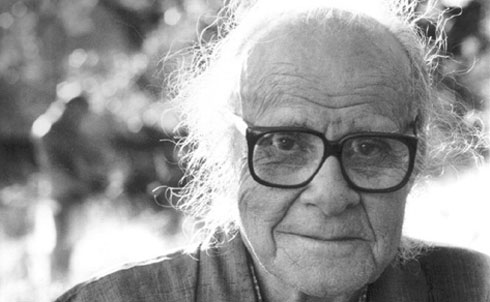

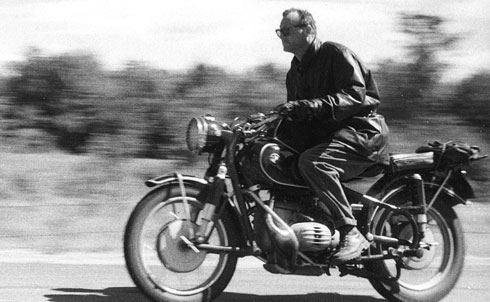

In the 1950s, when most social scientists were celebrating America’s postwar prosperity, Mills, a Columbia University sociologist, was warning about the dangers of the concentration of wealth and power in what he called, in his 1956 book of the same name, “the power elite.” He also warned about the US attitude toward Cuba in Listen, Yankee. Shunned by most fellow sociologists, his ideas—outlined in books, scholarly journals and many magazine articles—became popular among 1960s activists. Mills’s then-radical notion that big business, the military and government can be too closely connected is now conventional wisdom.

From The Nation‘s Archives:

The Balance of Blame by C. Wright Mills.

Further Reading:

The Power Elite by C. Wright Mills.

Radical Ambition: C. Wright Mills, the Left, and American Social Thought by Daniel Geary.

Credit: Yaroslava Surmach Mills

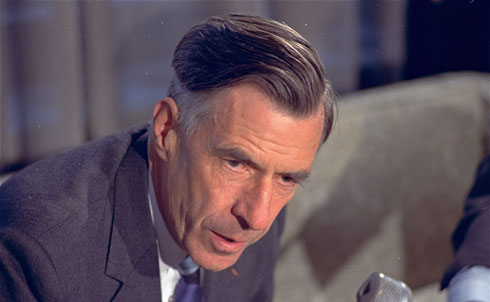

Galbraith was the century’s leading progressive American economist. His many books and articles helped popularize Keynesian ideas, especially The Affluent Society (1958), which coined the title phrase but also warned about the widening gap between private wealth and public squalor. In The New Industrial State (1967), the Harvard professor criticized the concentration of corporate power and recommended stronger government regulations. Active in politics, he served in the administrations of FDR, Truman, JFK and LBJ, including as Kennedy’s ambassador to India.

Further Reading:

The Affluent Society and The New Industrial State by John Kenneth Galbraith.

John Kenneth Galbraith: His Life, His Politics, His Economics by Richard Parker.

Credit: AP Images

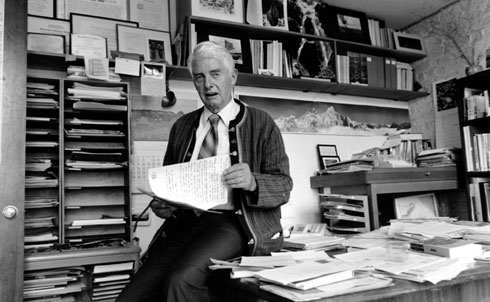

Brower, who began his career as a world-class mountaineer, was a pioneer of the modern environmental movement. He served as the Sierra Club’s first executive director from 1952 to 1969, expanding the group’s membership from 7,000 to 77,000 members. He led campaigns to establish ten new national parks and seashores and to stop dams in Dinosaur National Monument and Grand Canyon National Park. He was instrumental in gaining passage of the Wilderness Act of 1964, which protects millions of acres of public lands in pristine condition. He founded Friends of the Earth and then the League of Conservation Voters, mobilizing environmentalists for political action. In 1982 he founded Earth Island Institute to support environmental projects around the world.

Further Reading:

Wilderness: America’s Living Heritage by David Brower.

Encounters with the Archdruid by John McPhee.

Credit: AP Images

Seeger wrote or popularized “We Shall Overcome,” “Turn, Turn, Turn,” “If I Had a Hammer,” “Guantanamera,” “Wimoweh,” “Where Have All the Flowers Gone?” and other songs that inspired people to take action. On his own and as a member of the Almanac Singers and the Weavers (which had several top-selling hits, including “Good Night, Irene,” despite their opposition to commercialism), Seeger sang for unions, civil rights and antiwar groups and other human rights causes in the United States and around the world. He introduced Americans to the music of other cultures and catalyzed the “folk revival” of the late 1950s and ’60s. He was a founder of the Newport Folk Festival and Sing Out! magazine. He was also an environmental pioneer, founding the sloop Clearwater and raising consciousness and money to push government to clean up the Hudson River and other waterways.

From The Nation‘s Archives:

Songbag by Pete Seeger.

Further Reading:

Everybody Says Freedom: A History of the Civil Rights Movement in Songs and Pictures by Pete Seeger.

How Can I Keep From Singing? The Ballad of Pete Seeger by David King Dunaway.’

"To Everything There Is A Season": Pete Seeger and the Power of Song by Allan M. Winkler.

Credit: New York World-Telegram and the Sun Newspaper Photograph Collection (Library of Congress)

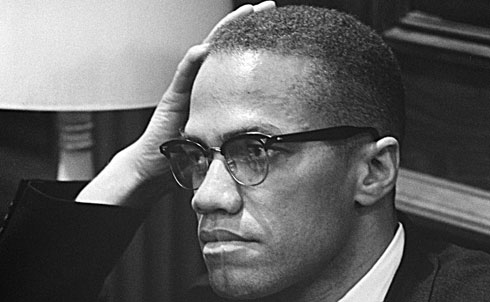

A onetime street hustler involved in drugs, prostitution and gambling, Malcolm Little converted to Islam while in prison and, upon his release, became a leading minister of the Nation of Islam, a forceful advocate for black pride and a harsh critic of white racism. As Malcolm X, he inspired the Black Power movement, which competed with the integrationist wing of the civil rights movement for the loyalty of African-Americans, and wrote (with Alex Haley) the bestselling The Autobiography of Malcolm X. His father—an outspoken Baptist preacher and avid supporter of Black Nationalist leader Marcus Garvey—faced death threats from the white supremacist organization Black Legion and was killed in 1931. As a popular minister for the Nation of Islam, Malcolm X preached a form of black separatism and self-help. One of his recruits was boxer Muhammad Ali. In 1964, disillusioned by Nation of Islam leader Elijah Muhammad’s behavior, Malcolm X left the organization. That year, he traveled to Mecca and, in his words, met “all races, all colors, blue-eyed blondes to black-skinned Africans in true brotherhood!” When he returned to the United States he had a new view of racial integration. He was shot and killed on February 21, 1965, after giving a speech in Manhattan’s Audubon Ballroom. Many suspect that Elijah Muhammad had a hand in his murder.

Further Reading:

The Autobiography of Malcolm X.

Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention by Manning Marrable.

Credit: U.S. News & World Report Magazine Photograph Collection (Library of Congress)

Her book The Feminine Mystique (1963) helped change American attitudes toward women’s equality, popularized the phrase “sexism” and catalyzed the modern feminist movement. In the 1940s and 1950s she worked as a left-wing labor journalist before focusing her writing and activism on women’s rights. She co-founded the National Organization for Women in 1966 and the National Women’s Political Caucus (along with Gloria Steinem, Fannie Lou Hamer, Bella Abzug and Shirley Chisholm) in 1971.

Further Reading:

The Feminine Mystique by Betty Friedan.

Betty Friedan and the Making of "The Feminine Mystique": The American Left, the Cold War, and Modern Feminism by Daniel Horowitz.

Credit: AP Images

His book The Other America (1962) exposed Americans to the reality of poverty in their midst. In his 20s, Harrington joined Dorothy Day’s Catholic Workers movement, lived among the poor at the Catholic Worker house and edited the Catholic Worker from 1951 to 1953. The Other America catapulted Harrington into the national spotlight. He became an adviser to LBJ’s “war on poverty” and a popular lecturer on college campuses, at union halls and academic conferences and before religious congregations. Inheriting Norman Thomas’s mantle, he was America’s leading socialist thinker, writer and speaker for four decades, providing ideas to King, Reuther, Robert and Ted Kennedy and other leaders. Harrington wrote fifteen other books on social issues and helped build bridges between left intellectuals and academics and the civil rights and labor movements. He encouraged activists to promote “the left wing of the possible.” He founded Democratic Socialists of America, which remains the nation’s largest socialist organization.

From The Nation‘s Archives:

The Myth That Was Real by Michael Harrington.

Further Reading:

The Other America: Poverty In the United States by Michael Harrington.

The Other American: The Life of Michael Harrington by Maurice Isserman.

Building on his experiences as a farmworker and community organizer in the barrios of Oakland and Los Angeles, Chavez did what many thought impossible—organize the most vulnerable Americans, immigrant farmworkers, into a successful union, improving conditions for California’s lettuce and grape pickers. Founded in 1960s, the United Farm Workers pioneered the use of consumer boycotts, enlisting other unions, churches and students to join in a nationwide boycott of nonunion grapes, wine and lettuce. Chavez led demonstrations, voter registration drives, fasts, boycotts and other nonviolent protests to gain public support. The UFW won a campaign to enact California’s Agricultural Labor Relations Act, which Governor Jerry Brown signed into law in 1975, giving farmworkers collective bargaining rights they lacked (and still lack) under federal labor law. The UFW inspired and trained several generations of organizers who remain active in today’s progressive movement.

From The Nation‘s Archives:

The Farm Workers’ Next Battle by Cesar Chavez.

Further Reading:

"The Mexican American and the Church" by Cesar Chavez.

Cesar Chavez: Autobiography of La Causa by Jacques E. Levy.

The Union of Their Dreams: Power, Hope, and Struggle in Cesar Chavez’s Farm Workers Movement by Miriam Pawel.

Why David Sometimes Wins: Leadership, Organization, and Strategy in the California Farm Worker Movement by Marshall Ganz.

Credit: AP Images

Milk was elected to San Francisco’s Board of Supervisors in 1977, making him the first openly gay elected official in California and the most visible gay politician in the country. He moved to San Francisco in 1972 and set up a camera shop in the city’s Castro district, quickly getting involved in local politics. Called “the mayor of Castro Street,” Milk was a charismatic gay rights activist who built alliances with other constituencies, including neighborhood and tenants’ groups. He became an ally of the labor movement by getting gay bars to remove Coors beer, which unions were boycotting for Coors’s opposition to union organizing in its breweries and the Coors family’s support for right-wing causes. As city supervisor, he orchestrated passage of a law that prohibited discrimination in housing and employment based on sexual orientation. In 1978 he led the opposition to a statewide ballot measure (the Briggs initiative) to ban homosexuals from jobs as schoolteachers. On November 27, 1978, he was killed by Dan White, a disgruntled former city supervisor who disagreed with Milk and Mayor George Moscone, whom he also assassinated that day.

Further Reading:

The Mayor of Castro Street: The Life and Times of Harvey Milk by Randy Shilts.

Credit: AP Images

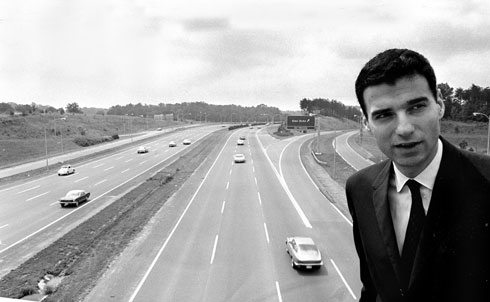

Since 1965, when he published his exposé of the auto industry, Unsafe at Any Speed, Nader has inspired, educated and mobilized millions of Americans to fight for a better environment, safer consumer products, safer workplaces and a more accountable government. Thanks to Nader, our cars are safer, our air and water are cleaner and our food is healthier. He raised awareness about the dangers of nuclear power and helped stop the construction of nuclear power plants. Nader played an important role in milestones such as the Freedom of Information Act, the Clean Air Act, the Safe Drinking Water Act, the Superfund program, the Environmental Protection Act, the Consumer Product Safety Commission and the Occupational Safety and Health Act. Nader built a network of organizations to research and lobby against corporate abuse, training tens of thousands of college students and others in the skills of citizen activism. He has written many books, all focusing on how citizens can make America more democratic. During the 1970s and ’80s Nader topped most polls as the nation’s most trusted person. He ran for president four times, most controversially in 2000, when as a Green Party candidate he won votes in Florida that may have cost Democrat Al Gore the election.

From The Nation‘s Archives:

How to Curb Corporate Power by Ralph Nader.

Fashion or Safety by Ralph Nader.

Further Reading:

Ralph Nader: A Biography by Patricia Cronin Marcello.

Credit: AP Images

Steinem helped popularize feminist ideas as a writer and activist. Her 1969 article “After Black Power, Women’s Liberation” helped establish her as a national spokeswoman for the women’s liberation movement and for reproductive rights. In 1970 she led the Women’s Strike for Equality march in New York along with Betty Friedan and Bella Abzug. In 1972 she founded Ms. magazine, which became the leading feminist publication. Her frequent articles and appearances on TV and at rallies made her feminism’s most prominent public figure. She co-founded the National Women’s Political Caucus, the Ms. Foundation for Women, Choice USA, the Women’s Media Center and the Coalition of Labor Union Women. In 1984 she was arrested, along with Coretta Scott King, more than twenty members of Congress and other activists, for protesting apartheid in South Africa. She also joined protests opposing the Gulf War in 1991 and the Iraq War in 2003.

From The Nation‘s Archives:

Why I’m Not Running For President by Gloria Steinem.

Further Reading:

"After Black Power, Women’s Liberation" by Gloria Steinem.

Gloria Steinem: Her Passions, Politics, and Mystique by Sydney Ladensohn Stern.

Credit: AP Images

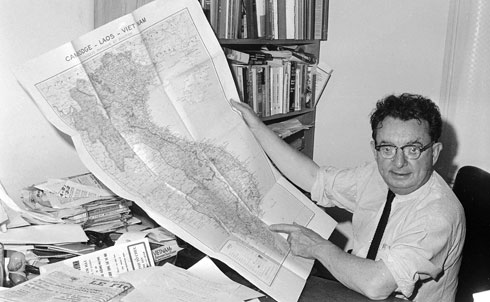

Hayden was a founder of Students for a Democratic Society in 1960 and wrote its Port Huron Statement, a manifesto of the postwar baby boom generation. He worked as a community organizer in Newark and helped link student activists to the civil rights movement and later the antiwar movement. He made several high-profile trips to Cambodia and North Vietnam to challenge US military involvement in Southeast Asia. Hayden was the first leading 1960s radical activist to run for major political office, challenging Senator John Tunney of California in the Democratic primary of 1976. He was later elected to the California legislature, where he served for eighteen years as an environmental and consumer advocate, while continuing his antiwar activism, gang intervention work and writing for The Nation and other publications. He is the author of seventeen books.

From The Nation‘s Archives:

Progressives for Obama by Tom Hayden.

Unfinished Business by Tom Hayden.

Further Reading:

The Port Huron Statement by Tom Hayden.

Reunion by Tom Hayden.

Democracy in the Streets by James Miller.

Credit: AP Images

As a candidate for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1984 and 1988, Jackson, a Baptist minister and aide to King, popularized the idea of a progressive multiracial and socially diverse “rainbow coalition.” After the 1965 march to Selma, Jackson moved to Chicago to head the city’s SCLC office and to start Operation Breadbasket and later Operation PUSH, which pioneered the use of boycotts and other pressure tactics to get private corporations to hire African-Americans and do business with black-owned firms. In his second bid for the White House, Jackson won seven primaries and four caucuses. He also gained influence by arranging exchanges or releases of US political prisoners in Syria, Cuba and Belgrade.

From The Nation‘s Archives:

For Jesse Jackson and His Presidency by The Editors.

Further Reading:

Legal Lynching: The Death Penalty and America’s Future by Jesse Jackson.

Jesse: The Life and Pilgrimage of Jesse Jackson by Marshall Frady.

Credit: John H. White

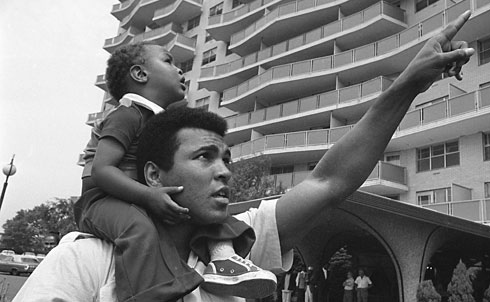

Born Cassius Clay in Louisville, Ali became an Olympic gold medal boxer in 1960, three-time heavyweight champion of the world, a highly visible opponent of the Vietnam War and a symbol of pride for African-Americans and Africans. He called himself “the greatest,” composed poems that predicted the round in which he’d knock out his next opponent and told reporters that he could “float like a butterfly, sting like a bee.” In 1964, soon after winning the heavyweight championship, he revealed that he was a member of the Nation of Islam, changing his name. Two years later, Ali refused to be drafted into the military, stating that his religious beliefs prevented him from fighting in Vietnam. He said, “No Vietnamese ever called me nigger,” a statement suggesting that US involvement in Southeast Asia was a form of colonialism and racism. The government denied his claim for conscientious objector status, and he was arrested for refusing induction. He was stripped of his heavyweight title, and his boxing license was suspended. He reclaimed the crown in 1974 by beating George Foreman in the so-called Rumble in the Jungle. For his boxing skills and political courage, he was among the most recognized people in the world in the 1960s and ’70s.

Further Reading:

The Greatest: My Own Story by Muhammad Ali.

King of the World: Muhammad Ali and the Rise of an American Hero by David Remnick.

Credit: AP Images

King was at the top of women’s tennis for nearly two decades. She won her first Wimbledon singles title in 1966, piled up dozens of singles and doubles titles before retiring in 1984 and was ranked number one in the world for five years. She founded the Women’s Tennis Association, the Women’s Sports Foundation and WomenSports magazine. She championed Title IX legislation, which equalized opportunities for women on and off the playing field. In 1972 she signed a controversial statement, published in Ms., that she had had an abortion, putting her on the front lines of the battle for reproductive rights. In 1972 she became the first woman to be named Sports Illustrated “Sportsperson of the Year.” In 1981 she was the first major female professional athlete to come out as a lesbian. She has consistently spoken out for women and their right to earn comparable money in tennis and other sports.

Further Reading:

Pressure Is a Privilege: Lessons I’ve Learned from Life and the Battle of the Sexes by Billie Jean King.

A Necessary Spectacle: Billie Jean King, Bobby Riggs, and the Tennis Match That Leveled the Game by Selena Roberts.

Credit: Michael Cole/Courtesy of HBO

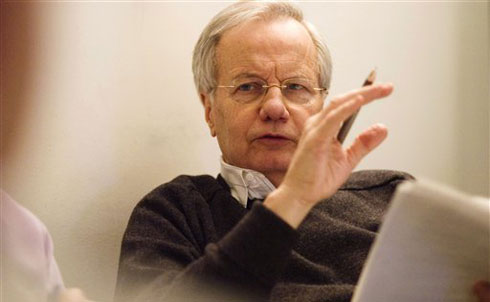

Moyers served as JFK’s deputy director of the Peace Corps, LBJ’s press secretary, publisher of Newsday and commentator on CBS, but he had his greatest influence as a documentary filmmaker and interviewer on PBS for three decades before retiring earlier this year. Following in the footsteps of broadcaster Edward R. Murrow, Moyers used TV as a tool to expose political and corporate wrongdoing and tell stories about ordinary people working together for justice. Like Studs Terkel, he introduced America to great thinkers, activists and everyday heroes typically ignored by mainstream media. Reflecting the populism of his humble Texas roots and the progressive convictions of his religious training (he is an ordained Baptist minister), Moyers produced dozens of hard-hitting investigative documentaries revealing corporate abuse of workers and consumers, the corrupting influence of money in politics, the dangers of the religious right, the attacks on scientists over global warming, the power of community and union organizing and many other topics. Trade Secrets (2001) uncovered the chemical industry’s poisoning of American workers, consumers and communities. Buying the War (2007) investigated the media’s failure to report the Bush administration’s propaganda about weapons of mass destruction and other lies that led to the war in Iraq. A gifted storyteller, Moyers, on the air and in the pages of The Nation and elsewhere, roared with a combination of outrage and decency, exposing abuse and celebrating the country’s history of activism.

From The Nation:

The Moyers Legacy by The Editors.

Further Reading:

Moyers on America: A Journalist and His Times by Bill Moyers.

Moyers on Democracy by Bill Moyers.

In twenty books and hundreds of articles in mainstream newspapers and magazines as well as progressive outlets, she has popularized ideas about women’s rights, poverty and class inequality and America’s healthcare crisis. Beginning with The American Health Empire (1971), Complaints and Disorders: The Sexual Politics of Sickness (1973) and other books, she exposed the way the healthcare system discriminates against women and the poor, helping efforts to change the practices of hospitals, medical schools and physicians. In The Mean Season (1987), Fear of Falling (1989), The Worst Years of Our Lives (1990) and Bait and Switch (2005), she exposed the downside of America’s class system for the poor and the middle class. Nickel and Dimed: On (Not) Getting By in America (2001), a bestselling first-person account of her yearlong sojourn in low-wage jobs, documented the hardships facing the working poor and helped energize the burgeoning “living wage” movement. She is co-chair of Democratic Socialists of America.

From The Nation:

The Communist Manifesto Turns 160 by Barbara Ehrenreich.

Further Reading:

Nickel and Dimed: On (Not) Getting By in America by Barbara Ehrenreich.

Credit: Sigrid Estrada

In the tradition of earlier muckraking journalists, Moore has used his biting wit, eye for human foibles, anger at injustice, faith in the common sense of ordinary people and skills as a filmmaker, author and public speaker to draw widespread attention to some of America’s most chronic problems. His first film, the low-budget documentary Roger & Me (1989), examined the tragic human consequences of General Motors’ decision to close its factory in Flint (Moore’s hometown) and export the jobs to Mexico. The Big One (1997) examined corporate America’s large-scale layoffs during a period of record profits, focusing on Nike’s decision to outsource its shoe production to Indonesia. His documentaries in the twenty-first century have explored America’s love affair with guns and violence (the Academy Award–winning Bowling for Columbine), the links between the families of George W. Bush and Osama bin Laden in the aftermath of September 11 (Fahrenheit 9/11), healthcare reform (Sicko) and the financial crisis and the political influence of Wall Street (Capitalism: A Love Story). Moore also directed and hosted two TV news magazine shows—TV Nation (1994–95) and The Awful Truth (1999–2000)—that focused on controversial topics other shows avoided. The author of several books of political satire—including Downsize This! (1996), Stupid White Men (2001) and Dude, Where’s My Country? (2003)—Moore is a frequent commentator on TV talk-shows and regularly speaks at rallies and events to help build a movement for economic and social justice.

From The Nation:

America’s Teacher, Naomi Klein in conversation with Michael Moore.

Further Reading:

Stupid White Men, Downsize This! and Dude, Where’s My Country? by Michael Moore.

Credit: AP Images

Peter Dreier’s list of most influential progressives isn’t intended to be complete—we needed you to help us fill out the picture! Once all 50 of the progressives Dreier selected appeared online, we asked you to nominate the American progressives you think made the biggest difference in the twentieth century—and the activists, advocates and politicians who are already defining the twenty-first. We received hundreds of submissions from across the country and the world, and we were able to narrow it down to the 11 most popular and most influential progressives nominated. View the reader-selected list here.

Credit: AP Images