The Nation’s editors—from its abolitionist founders to the present—have always provided space for those persistent and too-often lonely voices inveighing against the evils of racial injustice. In this archival slide show, we present a small sampling of the many timeless articles highlighting issues of race and civil rights from The Nation’s past 146 years.

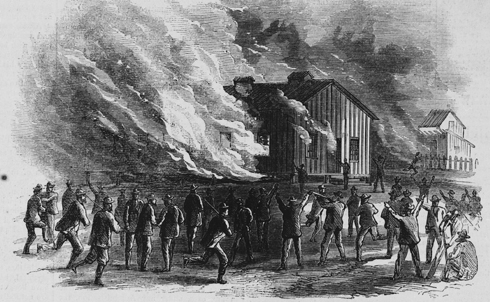

In the years after the Civil War, as the South braced for the withdrawal of Union soldiers, the protection of former slaves fell to often-hostile local police officers. Riots erupted in Memphis in 1866 following a clash between a group of black soldiers and white police officers, with police and civilians storming black neighborhoods to rob, rape and kill. The chaos lasted three days.

“There will prevail in the South for a long time to come a good deal of envy, hatred, and malice towards the colored population,” Nation co-founder E.L. Godkin wrote in his article in the aftermath of the Memphis riots, foreshadowing the difficult road ahead for African Americans. In the riots, Godkin says, “the officers of the law…took a leading part in it, and we now have very little doubt that, were any similar outburst of popular prejudice to take place tomorrow in any other town in the South, the local police, if they interfered at all, would interfere in the same way.”

Credit: Harper’s Weekly / Library of Congress

In 1909, in part to counter instances of open disregard for African-American life such as had occurred in Memphis and was still occurring over forty year’s later, a coalition of leading writers and intellectuals gathered in New York City to establish the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

The Nation’s Oswald Villard—grandson of the prominent abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison and this magazine’s editor for over a decade in the early years of the twentieth century—was integral to the founding of the new organization, and “his fearless and outspoken determination…held the group together in the early and difficult years,” Flint Kellogg wrote in 1959. By the time Villard left the organization, it was, in the words of NAACP director W.E.B. Du Bois, “out of debt, aggressive, and full of faith.”

Credit: Library of Congress

Following the First World War, thousands of African-American soldiers returned from abroad to find they were still considered inferior Americans. The post-war demobilization meant job-loss for many Black Americans who now had to fight desperately for employment with whites, who were given preference.

It was in this climate that Marcus Garvey founded the Universal Improvement Association. With millions of members from across the world, the association rallied around self-determination for Africans, and vowed to create a Republic of Africa governed by Africans. “Neither Garvey nor any other human being could ever build up such a movement among the masses if it did not answer some longing of their souls,” William Pickens wrote in 1921. “His particular movement may fail; the new racial consciousness of the Negro will endure.”

Credit: Everett Collection

In 1926, the Harlem Renaissance was in full flower and the poet Langston Hughes was one of its central figures. In his classic Nation essay, “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain,” Hughes urged black intellectuals and artists to embrace their cultural heritage and identity.

“I am ashamed for the black poet who says, ‘I want to be a poet, not a Negro poet,’ as though his own racial world were not as interesting as any other world,” Hughes wrote. “An artist must be free to choose what he does, certainly, but he must also never be afraid to do what he might choose….If white people are pleased we are glad. If they are not, it doesn’t matter.”

Credit: Everett Collection

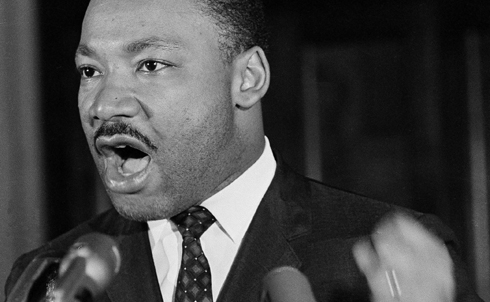

The calls for justice of the activists and organizers of the first half of the twentieth century gave way to full-throated cries for racial equality in the fifties and sixties. The most visible civil rights advocate, Martin Luther King Jr., wrote several essays for The Nation on the state of race relations in America, in which he outlined the overwhelming challenges facing the movement.

“Having gained a measure of success they are now revealed to be clothed, by comparison with other Americans, in rags,” King wrote of African Americans in 1965. They are housed in decaying ghettoes and provided with a ghetto education to eke out a ghetto life…Only when they are in full possession of their civil rights everywhere, and afforded equal economic opportunity, will the haunting race question finally be laid to rest.”

Credit: AP Images

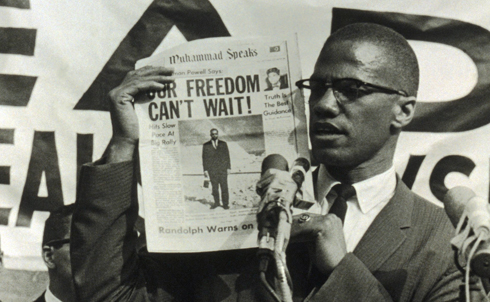

A onetime street hustler involved in drugs, prostitution and gambling, Malcolm Little converted to Islam while in prison and, upon his release, became a leading minister of the Nation of Islam, a forceful advocate for black pride and a harsh critic of white racism. In 1964, disillusioned by Nation of Islam leader Elijah Muhammad’s behavior, Malcolm X left the organization. That year, he traveled to Mecca and, in his words, met “all races, all colors, blue-eyed blondes to black-skinned Africans in true brotherhood!” His views continued to evolve. He spoke against white racism, the capitalist system and imperialism. In 2010, The Nation named Malcolm X one of its top 50 most influential progressives of the twentieth century.

Credit: Everett Collection

In 1963, Greenwood, Mississippi was the headquarters of the Voter Registration Project, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee-led effort to enfranchise the voters of a county in which almost no African-Americans voted and those who did faced violent retribution.

From this hotbed of agitation and anger, a young Howard Zinn reported for The Nation on the trials and intimidation SNCC’s activists faced. The South needed basic and thorough-going changes, Zinn wrote, which could only come about through radical new uses of initiative and power from the national government. But because the administration lacked the basic motivation to make such changes, the future depended, for Zinn, on “the increased use of nonviolent direct action.”

Credit: AP Images

Beginning in the Los Angeles neighborhood of Watts in 1965, urban riots erupted across America in the late-sixties, symptomatic of the nation’s failure to address the poverty and discrimination still disproportionately burdening blacks. The Watts rebellion lasted six days, thirty-four people were killed and more than a thousand were injured.

For Carey McWilliams, editor of The Nation from 1955 to 1975 and an expert on his native Southern California, the root causes of the Watts riot lay in the “general unawareness that a minority is festering in squalor.” The new Los Angeles middle class, “living in jerry-built ‘lily white’ subdivisions, each with its own shopping-center, can honestly claim to be no more aware of Watts than the nice Germans were of Belsen.”

Credit: AP Images

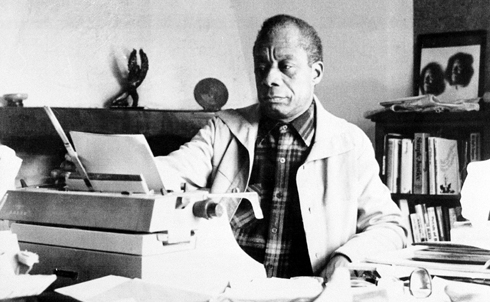

During the 1980 presidential race, James Baldwin—author and member of this magazine’s editorial board until his death—wrote that “No black citizen of what is left of Harlem supposes that either Carter, or Reagan, or Anderson has any concern for them at all, except as voters—that is, to put it brutally, except as instruments.”

Credit: AP Images

By the eighties, the open violence of the lynch mob had largely given way to insinuations of intractable racial inferiority peddled by a mainstream media more than happy to claim that the problems facing African-Americans were self-made. In his 1989 essay, “The Black Pathology Biz,” Ishmael Reed wrote that from their depiction of street gangs to crack use to unemployment to unwanted pregnancies, the media makes their money by “putting out the lie that US crime is black.”

Credit: AP Images

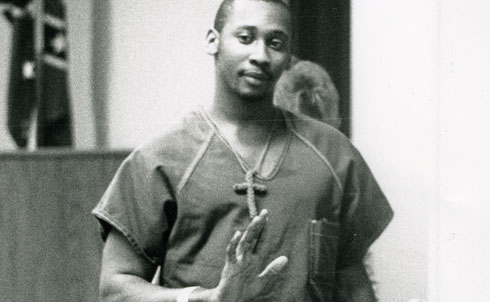

In 1989, a black man named Troy Davis was convicted of murdering a white police officer in Georgia’s Chatham County—this despite the fact that no physical evidence linked Davis to the crime, no murder weapon was ever found and several witnesses later said that police coerced them into testifying. Figures such as Jimmy Carter, Al Sharpton and Desmond Tutu have joined the grassroots appeals for the courts to retry Davis, but he remains on death row.

After NAACP President Benjamin Jealous visited Davis in prison in 2009, he said that the case echoed “the long, sour history of wrongly-accused black men receiving ‘rough justice’ in the Deep South.” That any American “might be sentenced to death without being allowed a full airing of all the evidence is an outrage,” Jealous wrote, “and represents a blatant flouting of our nation’s founding principles.”

On the eve of Davis’s execution on September 21, 2011, The Nation expressed the sad fact that "There will not be justice for Troy Davis. But his case has reawakened Americans to a relic of injustice that must be abolished once and for all."

Credit: AP Images

O.J. Simpson’s hyper-publicized murder trial brought the role of race in the justice system into the spotlight in 1995, as pundits perversely insisted that this was our chance to make a troubled judicial history right and assuage the fears of all black Americans. “How random and shallow the discontent must seem if O.J. Simpson is made the measure of black oppression,” Patricia Williams wrote at the time, “just another example of playing the race card.”

Credit: AP Images

Laws against interracial marriage remained on the books far longer than many Americans realize: by the 1967 Supreme Court ruling outlawing such prohibitions, sixteen states still had statutes against marriage across racial lines.

But over thirty years later, in 2000, Alabama still had a century-old constitutional provision barring interracial marriage. “That an expression of official opposition to interracial marriage remained a part of the Alabama Constitution for so long reflects the fear and loathing of black-white intimacy that remains a potent force in American culture,” Randall Kennedy wrote at the time. “Sobering, too, was the closeness of the vote; 40 percent of the Alabama electorate voted against removing the obnoxious prohibition.”

Credit: AP Images

Instead of the yearly ritual of celebrating black history through sixty-second soundbites, Patricia Williams wrote in 2000, Americans would do better to reflect on the multifaceted roots of our complicated racial legacy.

The traumas of Jim Crow, race riots, thwarted desegregation and ongoing oppressions less overt all yielded collective scars, and whites as much as blacks have been shaped by this history. “This does not mean that white racism is by any means more burdensome for whites than for blacks,” Williams wrote. All she recommends is that as Americans, we must “feel ourselves unsettled by the full truth of these historical horrors before we commend ourselves for having buried the past.”

Credit: AP Images

In 2008, America chose the child of a black father and a white mother to serve in the highest office in the land. Barack Obama shattered the presidential color barrier in an election that few dreamed they would ever witness. For veteran civil rights leader Rev. Jesse L. Jackson—who himself had gone from being jailed for trying to use a public library to twice running for president—that an African-American could be president was an emotional and hard-won victory.

But in a speech delivered that summer, Jackson warned then-candidate Obama, “To fight for the poor you must first fight their monitors, their overseers, their predators, their subprime lenders and their drug and gun suppliers.” Only when all Americans were freed from these institutional restraints could true democracy flourish. “If the poor got a return on their vote, their dollars, their work,” Jackson said, “they would end poverty.”

Credit: AP Images

As The Nation’s Peter Rothberg explains, though we’ve amazingly elected an African-American president, and though “demographics are quickly bringing us to the days of ‘minority majorities,’ a significant measure of prejudice and discrimination remains persistent and pernicious.”

This Black History Month, Rothberg has assembled a list of groups, organizations and websites working to confront this stain on the American Experiment. A great way to celebrate the month would be to join and support their work.

Credit: Reuters Pictures

Research for this slide show provided by Sara Jerving