You can read all of the pieces in The Nation’s special issue on drug policy here.

Though The Nation has long championed drug policies that focus on harm reduction over punishment and prohibition, in 1895 the magazine called on the international community to put a stop to the British opium trade in China and India, which it labeled a crime “of the deepest dye.” To combat the self-interested British drug empire, The Nation even advocated outlawing opium, and printed a petition signed by Mahatma Gandhi in 1924 urging world leaders to stop opium’s spread in the name of human rights.

But over the next century, as the US’s own drug laws became more punitive and hypocritical, The Nation consistently decried the misguided attempts at regulation and contradictory, uneven enforcement that have turned our national fascination with intoxicating substances into a self-perpetuating cycle of inequality and disenfranchisement for vast numbers of Americans.

For our special issue dedicated to drug policy, we have assembled a collection of articles and images from The Nation’s archives chronicling our country’s long history of substance follies, abuses and successes.

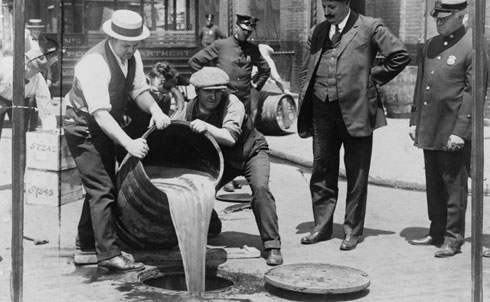

Credit: Library of Congress

One of the country’s first experiments in the wholesale ban of a substance was the prohibition of alcohol, which—after decades of agitation by the loose coalition of churches, progressive groups and tea and soda companies that made up the temperance movement—became national law when the Eighteenth Amendment went into effect in 1920.

But the costs of enforcing a nationwide substance ban and the widespread bootlegging and mafia influence that resulted soon made the legislation unpopular. What’s more, "the kind of boozing that" Prohibition induced, wrote H.L. Mencken in The Nation, "was so reckless and so plainly dangerous that it alarmed wets as well as dry." In 1934, a year after Prohibition’s quick repeal, Mencken said that "the prohibition brethren looked for a gaudy Saturnalia of boozing, very useful to their cause," to follow the legalization of alcohol. Fortunately for repeal agitators and for the country as a whole, no such widespread alcohol abuse followed, and government regulation of the previously contraband substance reined in excess and took the "exhilarating naughtiness" out of drink for many Americans.

Credit: New York World-Telegram and the Sun Newspaper Photograph Collection (Library of Congress)

But while America’s Noble Experiment outlawing alcohol ultimately failed, the prohibition of drugs persisted and found its champion in Federal Bureau of Narcotics commissioner Harry J. Anslinger. For Anslinger, who got his start as a Prohibition enforcer, the drug addict was an "immoral, vicious, social leper," and from the FBN’s creation in 1930 to 1962, his beliefs dictated national drug policy. One of his early "victories" was the 1937 outlawing of marijuana, achieved through infamously racist rhetoric and wildly false descriptions of the drug’s effect. As The Nation‘s Stanley Meisler wrote in 1960, it was Anslinger’s long tenure at the head of FNB that pushed Congress to pass ever-stricter narcotics laws and ensured that "in the United States, unlike almost every other Western nation, narcotics [remained] a police problem."

Credit: AP Images

Despite Anslinger’s draconian drug policies, by the mid-fifties heroin and morphine had hit America hard, and the country had become "the hub of the drug traffic in the Western hemisphere." "There are probably more addicts in the United States than in all of the other Western nations combined," wrote Alfred R. Lindesmith in The Nation in 1956, "and more juvenile users in New York City than in the whole of Europe." That year, Lindesmith identified the idiosyncratically American root of the problem, in terms that are still startlingly familiar over half a century later: "The disastrous consequences of turning over to the police what is an essentially medical problem are steadily becoming more apparent as narcotic arrests rise each year to new records and the habit continues to spread."

Credit: AP Images

For the first half of the twentieth century, wrote Mervin B. Freedman and Harvey Powelson, "drugs were used almost exclusively by those clearly out of step with conventional American life." But after the pioneering psychedelic drug experiments of Timothy Leary and his Harvard colleagues in the early 1960s, drugs became a prominent part of the student and hippie counterculture movements. As Freedman and Powelson reported in 1966, "there are now few colleges and universities where marijuana and the new psychedelic drugs, chiefly LSD, are not consumed." But drug use still retained its outlaw allure: disillusioned with American life and values, opposed to American intervention in Vietnam and angered by the ongoing oppression of African Americans and other disadvantaged minority groups, Freedman and Powelson wrote, drug-taking students "get pleasure from sharing a rebellious, illegal activity."

Credit: Derek Redmond and Paul Campbell

The backlash against the drug culture of the sixties and seventies was swift and severe. New York State Governor Nelson Rockefeller set the tone for much legislation to come when in 1973 he introduced an aggressive anti-drug law package that made selling or possessing any controlled substance punishable by up to life in prison. The Nation opposed the laws from the beginning, and Carol Trilling noted at the time that the Rockefeller drug laws were primarily aimed at assuaging "the white majority of the state’s residents, who were thrown into terror by the escalation of the drug ‘menace,’" but that in actual practice the laws would only exacerbate the state’s drug problem. By 2001, The Nation‘s editors could state that, "No single moment in the history of US criminal justice matches the destructive impact of the New York legislature’s 1973 session," when "the ancestor of just about every regressive criminal justice policy since enacted—three-strikes laws, federal sentencing guidelines and zero-tolerance police sweeps"—became law.

Credit: AP Images

From his election in 1980 through the end of his second term, President Ronald Reagan waged his “War on Drugs” by cynically painting drug users as violent criminals in a way that, according to Nation writers Harry Levine and Craig Reinarman, focused the American public’s "political attention on individual deviance and immorality and away from questions of economic inequality and injustice." Reagan’s tough approach to drugs yielded a wildly expensive drug enforcement bill and random drug testing for federal employees that critics called unconstitutional. As former-Yippie Abbie Hoffman wrote in The Nation in 1987, the "Harsher penalties, urine testing, hysteria, budget cuts and the simplistic ‘Just Say No!’ campaign (the equivalent of telling manic depressives to ‘just cheer up’)" of the Reagan era "returned drug education and treatment to the Reefer Madness era."

Credit: Everett Collection

The HIV/AIDS pandemic that swept the country in the 1970s and 80s spread especially rapidly among drug users. According to The Nation‘s William A. Schwartz, about one-fifth of national AIDS cases in 1987 involved drug users sharing dirty hypodermic needles. But authorities resisted the most commonsense methods to halt the spread of infections, and even played "an active role in perpetuating the disease by maintaining laws against the sale of sterile hypodermic needles and syringes without a doctor’s prescription."

The campaign for "needle exchanges" met with little public support in large part because, as Schwartz argued, "there is profound contempt for addicts in our society, reinforced by racism, as they are primarily black or Hispanic and poor." Drug officials also feared that making needles more available would lead to an increase in drug users. But activists and health policymakers pushed hard to legalize the practice, and by 1993, The Nation reported that needle exchange programs had begun in several cities across the country.

Credit: Reuters Pictures

One of the most consistent critiques leveled against the drug war has been its unequal and particularly damaging impact on communities of color. In this, drug policy and law enforcement officials have often been abetted by a sensationalist media. The reason: "Black pathology is big business," argued author Ishmael Reed in The Nation in 1989. "According to the news shows," Reed wrote, "you’d think that two black gangs, the Crips and the Bloods, are both the cause and the result of the nation’s drug problem, even though this country was high long before these children were born."

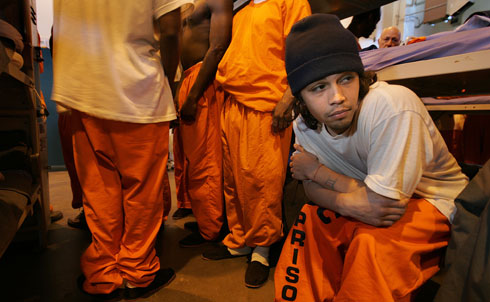

Credit: AP Images

The result of inflammatory media coverage, overzealous policing, and inadequate resources for prevention and treatment was clear, as Mike Massing argued in a special issue of The Nation dedicated to drug policy in 1999: "even a casual glance at the prison stats reveals that, by accident or design, the drug war has turned into a race war." The solution, Massing wrote, lay not in restructuring the failed prohibition-style approach to drug policy, but in legalization: "Legalization means regulation, not chaos. Chaos is what we’ve got now. Legalization means state control instead of mob control."

Credit: AP Images

Legalization and government regulation of drugs would reduce the influence of the criminal syndicates that currently profit off their monopoly of the drug trade. US drug addications have for decades funneled money into the pockets of outlaw drug gangs from Afghanistan to Colombia, Panama to Mexico. Last year, when Mexican President Felipe Calderón cracked down on his country’s drug cartels, violence flared up across Mexico and spilled into American border states. According to The Nation‘s Peter Schrag, the violence was "ironic because Americans, as everybody knows, buy and consume most of the marijuana, cocaine and methamphetamines that make up the lion’s share of the cartels’ business." Despite the continued focus on Mexico and states further south, perhaps "the real cause of the drug violence now drawing anxious attention from Congress, the Obama administration and worried state and local law enforcement officials lies on this side of the border."

Credit: Reuters Pictures

The Nation has long argued for liberalization of this country’s drug policies, and in this year’s elections, the magazine’s editors urged California voters to support Proposition 19. The failed ballot initiative would have legalized marijuana in the state, freed up the estimated $1.87 billion California currently spends on prohibition and relieved a strained police force that currently arrests black adults "for pot possession at higher rates than whites—sometimes by a factor of three or four."

A successful Prop 19 would have been a great victory for advocates for a sane national drug policy, but the fact that the initiative garnered support from 46.5% of voters is heartening to drug reform advocates. As the Drug Policy Alliance’s Ethan Nadelman argues, “The prospects for reforming drug policy have never been so good. The persistent failure and negative consequences of drug war policies, combined with budgetary woes and generational change, are mainstreaming reformist ideas once considered taboo.” You can read Nadelman’s full article and the rest of The Nation’s special drug policy issue here.

Credit: Reuters Images