We recently inaugurated Lived History, a new section of TheNation.com designed to honor, remember and pay tribute to the dearly departed who have made significant contributions to bettering our world. Each week we feature a remembrance of a member of the progressive community, either well known or more obscure, whose remarkable accomplishments demand recognition. In the process, we hope to be able to highlight and recover some of the more important but often obscure periods of our history that demonstrate the progressive tradition in American life. Here are a few of the notable individuals we lost in 2010.

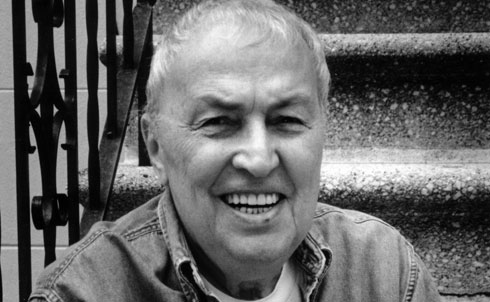

Howard Zinn was often labeled a dogmatic historian, but as The Nation’s editors wrote earlier this year, Zinn’s contributions to this magazine “reveal something else entirely: a pragmatic radicalism. He was interested in inspiring people to be agents of change, and he assembled from history, literature, philosophy and reportage a formidable intellectual and moral toolbox for doing it.” The Boston University historian and political activist was an early opponent of US involvement in Vietnam, but definitively made his mark on intellectual and public life as the author of the seminal A People’s History of the United States, a progressive retelling of the nation’s five-century journey from Columbus to the present. He passed away in January at the age of 87 of a heart attack in Santa Monica, California.

Credit: AP Images

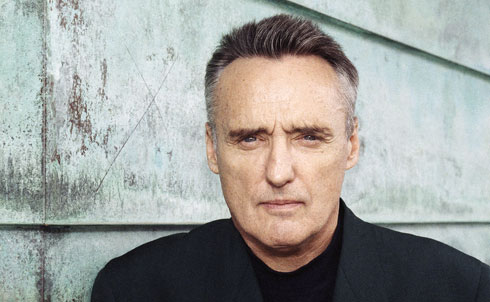

“Dennis Hopper was an easy and uneasy rider,” Katrina vanden Heuvel wrote when the actor, director and artist died this May, “unmortgaged to the Hollywood that had launched him as the rebellious young man. He never stopped living an original life—rough, tough, dangerous, defying the odds—and on his own terms.” As Viggo Mortenson explained in his tribute to his friend, Hopper’s influence on all those around him “manifested itself in his unceasing interest in people and their behavior, in the unpredictability of life—an openness that has often involved changing his mind and letting go of pre-conceived notions regarding art and morality in his life, and in the lives of others.

Credit: AP Images

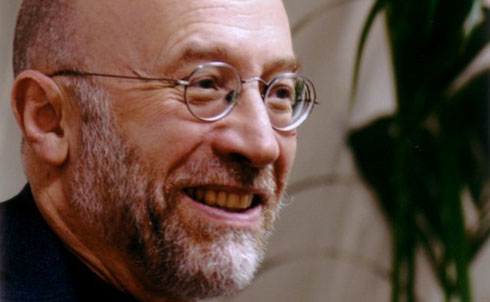

“It is difficult to describe the place that Grand Street held in the literary and political landscape of the 1980s,” Maria Margaronis wrote of the quarterly headed by writer, publisher, boulevardier Ben Sonnenberg. “It was sui generis, eclectic and unclassified; it stood,” as did it’s editor, who died this June, “at a slight angle to the universe.”

Credit: Sylvia Plachy

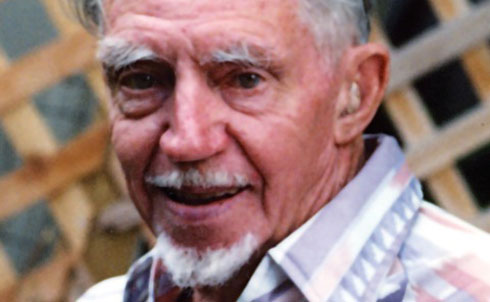

Over his five decades of writing, David Markson created idiosyncratic novels that pushed storytelling to the edge of understanding. As Joanna Scott wrote after the author’s death in June, the man who wrote Wittgenstein’s Mistress, Reader’s Block and, his last novel, The Last Novel, “composed a moving story about the struggles of a fictional writer who keeps working despite the indifference of the public. He may be old, tired, alone, broke and fatally sick at the end, but as long as he can discover other artists to admire, he doesn’t lose heart.”

Credit: Johanna Markson

The historian and intellectual Tony Judt was a man of the left who belonged to no party or ideological faction, “whose judgments,” wrote Eyal Press, “were grounded in the messy whirl of human experience rather than the shifting political currents of the day.” When the famed author of Postwar: A History of Europe Since 1945, Reappraisals: Reflections on the Forgotten Twentieth Century and Ill Fares the Land passed away this August from Lou Gherig’s disease, the world lost a thinker whose acumen, courage and range are renowned, profound and an inspiration.

Credit: John R. Rifkin

Chalmers Johnson’s all-American odyssey led him from his beginnings as a lieutenant junior grade assigned to a Navy “rust bucket” without a name at the end of the Korean War and subsequent supporter of the US war in Vietnam to his final mission of documenting and denouncing the US military’s “unacknowledged empire.” For the last decade before his death in November, wrote Tom Engelhardt, Johnson “never stopped warning the rest of us that if we didn’t choose to dismantle our empire ourselves, far worse would be in store for us.”

Credit: theendofpoverty.com

The career of the tough and hyper-energetic diplomat Richard Holbrooke spanned more than four decades, and as Barbara Crossette writes, left a legacy of triumph and controversy in its wake. “When Holbrooke died on December 13, Afghanistan was still a work in progress, and perhaps, as diplomats with long experience in the region suggest, an assignment he should never have been given.”

Credit: Reuters Pictures

“Elizabeth Edwards was a distinct political figure,” John Nichols explained of the attorney and activist wife of John Edwards, a figure who was consistently willing to stake out more dynamic and detailed positions than her husband. A longstanding advocate of universal healthcare and gay marriage, toward the end of her life Edwards took up one final crusade against the misguided conflict in Iraq. As Nichols wrote, when one of the most prominent women in America embraced Cindy Sheehan’s demand that George Bush listen to antiwar voices, it mattered.

Credit: AP Images

“Even if you don’t know a rebus from an anagram or a double-entendre from a pun,” wrote Judith Long, “you have no doubt noticed Frank W. Lewis‘s cryptic crossword puzzle each week on the last page of the magazine.” Frank, who died peacefully November 18 at the age of 98, had supplied The Nation with his brain-teasing (some would say brain-frying) puzzles from 1947 until his retirement at the end of 2009. Frank was a true Renaissance man, a lover of music (in which he had an advanced degree), history, literature, language, botany, mythology, geography, the military, sports, boating, cards—the list is endless—all of which enliven his puzzles.

After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, Frank Emi, a Los Angeles grocer, was among the approximately 110,000 law-abiding Japanese-Americans in the US who were suddenly regarded as threats to national security and herded by federal authorities to detention camps, where they spent most of World War II living under armed guard without any recourse to due process. But when the Roosevelt Administration decided in early 1944 to reopen the draft to Japanese American men in the camps, Emi and other detainees formed the Fair Play Committee to ask how they could be ordered to fight for freedom and democracy abroad when they were denied liberty at home. Emi was the last surviving member of the committee when he passed away this December, a man who acted courageously in the face of one of America’s most dishonorable historical episodes.

Credit: AP Images