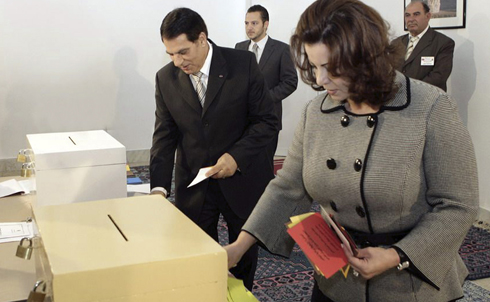

Since December 17, Tunisia has been in turmoil as thousands have taken to the streets to protest unemployment, high food prices, corruption and repression. The uprising began when Mohammed Bouazizi, an unemployed university graduate, set himself on fire after police confiscated the unlicensed cart he used to sell produce on the street. Despite police efforts to quell the unrest, the protests only increased in strength until President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali fled into exile in Saudi Arabia on January 14.

Prime Minister Mohamed Ghannouchi announced almost immediately he would replace the president and an interim government was named to serve until elections could be held. But as The Nation’s Laila Lalami explains in “Tunisia Rising,” the Tunisian people weren’t satisfied with this response and have continued to stand in opposition to the domination of the new cabinet by members of Ben Ali’s party.

Credit: Reuters Pictures

A North African nation with a population of more than 10 million people, Tunisia has long been considered an ally of the US because of its hard-line against terrorism. Because of the country’s large middle-class, good economic growth and high levels of education, the West considered Ben Ali’s Tunisia a “moderate Muslim nation.”

Despite this, Ben Ali, who ruled the country for 23 years, was a repressive leader who routinely won previous elections with 90 percent of the vote. Tunisia’s unemployment rate among college graduates has been reported as high as 20 percent, police repression and corruption is rampant, the president’s wife has been accused of stealing vast amounts of wealth from the nation and state censorship leaves citizens with few freedoms.

Before his departure, Ben Ali made one last attempt at quelling the protests by offering to not seek re-election in 2014 and said he would give the people more freedoms, all to no avail.

Credit: Reuters Pictures

Traditional media in Tunisia, blocked by censorship, was not at the disposal of the rioting masses. Instead social media outlets like Facebook, Twitter and blogs became the mouthpiece of the protestors. The Tunisian government made it a priority to block bloggers and others perceived as threats. Police arrested bloggers for posting dissenting blog posts and arrested a 22-year-old Tunisian rap singer Hamada Ben-Amor in January after he released a song—“President, your people are dying”—that went viral on the Internet.

Lalami writes that the uprising was the work of men and women on the ground, braving intimidation, beatings, tear gas and bullets: “In this modern revolution, the protesters had access to Internet tools that made it easier for them to get the word out, but those tools on their own could not topple a dictator.”

Credit: Reuters Pictures

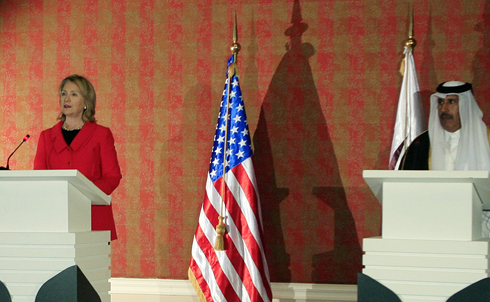

In its first weeks, the mainstream American press ignored the protests. The Washington Post reported on them for the first time on January 5, and Time ran its first piece on the revolution on January 11. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton had been on a tour in the Arab Gulf nation during that time, pressing Gulf countries to move toward democratic reforms—but failed to mention any of the unrest in Tunisia. President Obama made a statement acknowledging the riots only after Ben Ali had fled.

The initial disinterest of the American press in the Tunisian protests may have something to do with the fact that there was no Islam angle, explains Lalami: “the Tunisians were not trying to oust an Islamic regime, nor were they themselves supporters of a religious ideology. In other words, this particular struggle for freedom was not couched in simple terms that are familiar to the Western media—Islam, bad; America, good—so it took a while for our commentariat to notice.”

Credit: Reuters Pictures

Some media outlets have credited WikiLeaks with pushing the Tunisians toward revolution. As The Nation’s Robert Dreyfuss reports, the leaked US State Department cables highlight the popular resentment of the nation’s growing corruption. In one cable from 2008, an American diplomat writes that Tunisian corruption was getting worse all the time: “Whether it’s cash, services, land, property, or yes, even your yacht, President Ben Ali’s family is rumored to covet it and reportedly gets what it wants….Although the petty corruption rankles, it is the excesses of President Ben Ali’s family that inspire outrage among Tunisians.” In a country with rising inflation and high unemployment, the cable said, “the conspicuous displays of wealth and persistent rumors of corruption have added fuel to the fire."

Credit: Reuters Pictures

Will Tunisia’s example ripple throughout the Arab world as frustration towards other repressive leaders, such as Egypt’s Hosni Mubarak, continues to grow?

In “North African People of Power,” Karima Bennoune writes that Tunisia’s “largely peaceful, democratic revolution (on the side of the opposition at least) was not led by or inspired by the fundamentalist movements that have tried to claim the oppositional space in many Arab and North African contexts in recent years. It was instead, by all accounts, a largely secular appeal for real political reform and for social justice. As reflected in today’s front page of the Paris daily Liberation, women, many unveiled, were increasingly visible in the protest marches.”

Credit: Reuters Pictures

The future is unclear for Tunisia. Tunisia’s new coalition government is already facing trouble—a few ministers have quit and the opposition party is threatening to walk out if members of the party of the cast out president aren’t thrown out.

As Lalami writes, “The revolution is not over. In fact, it may have just begun. The Tunisian people are expecting justice for those who died, free and fair elections, and a new political order. But the three biggest lessons of their uprising have already been delivered far and wide. To the Arab dictators: you are not invincible. To the West: you are not needed. And to the Arab people: you are not powerless.”

Research for this slide show provided by Sara Jerving

Credit: Reuters Pictures