When Governor Walker announced his proposal to strip public employees of most collective bargaining rights on February 11, 2011—little over a month after taking office—he knew he would hear trouble from the historically progressive, pro-labor state of Wisconsin. He even threatened to call out the National Guard if things got too rowdy from the shock. Walker’s change of stance was radical, since he had never discussed ending collective bargaining during a campaign that emphasized working across lines of partisanship and ideology to create jobs.

The following slides track the key events of those early days and the following long months of the Wisconsin Uprising.

Credit: AP Images

On Valentine’s Day, February 14, the first stirrings of protest began as high school students staged a walk-out and University of Wisconsin at Madison students sent valentines to Walker reading "We ♥ UW: Don’t Break My ♥.”

Credit: AP Images

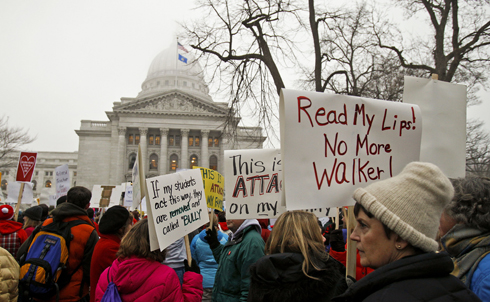

The following day, more than ten thousand protesters marched on the Wisconsin State Capitol in Madison, with signs bearing the influence of the recent overthrow of Egyptian dictator Hosni Mobarak, such as “Protest Like an Egyptian” and “If Egypt Can Have Democracy, Why Can’t Wisconsin?”

Tens of thousands more protesters flooded the Capitol over the course of that first week, culminating in a massive protest on Saturday that drew at least 80,000 opponents of Walker’s bill.

Credit: Reuters Pictures

Less than a week after Walker proposed his budget-repair plan, on February 17, all fourteen Democratic senators protested the move by fleeing across state borders to Illinois, depriving Republicans of the quorum needed to vote on the bill. After the massive outcry against Walker’s plan, John Nichols explained how Wisconsin was now acting out the American ideal that “Democracy does not end on election day. That’s when it begins. Citizens do not elect officials to rule them from one election to the next. Citizens elect officials to represent them, to respond to the will of the people as it evolves.”

Credit: Reuters Pictures

From the beginning of the opposition to Walker’s bill, the State Capitol served as the center of the protests, and Wisconsin’s long history of keeping the building open to all allowed for a truly democratic airing of dissent. After Walker threatened to restrict access to the building, protesters began camping out in the rotunda to ensure that their voices would be heard, paving the way for tactics that would later be used in the fall’s Occupy Wall Street movement.

Credit: AP Images

Calls were pouring into legislators’ offices denouncing the bill, so when Walker got a call on February 23 from an “ally,” it was a welcome change for the governor. Walker answered the call from “David Koch” with a hearty “Hey, David!”

The only problem? The call wasn’t actually from the billionaire libertarian behind Koch Industries and a slew of far-right causes. It was actually a prank orchestrated by Buffalo Beast’s Ian Murphy. Over the course of the twenty-minute call, Walker discussed how he had considered planting trouble-makers among the protesters and how Koch Industries clearly had a vested interest in getting the union-busting legislation passed.

Credit: AP Images

In a rapid and heated committee session on March 9, Senate Republicans circumvented the quorum requirements of the Senate by removing all elements of the bill related to spending and pushed the legislation through with a final vote of 18-1 with all fourteen Democratic senators still in Illinois. The bill in its amended form severely limited public employees’ collective bargaining rights and included other provisions intended to cripple public sector unions. Cries of “Shame! Shame! Shame!” were audible from the thousands of Wisconsinites assembled outside the Capitol to protest the highly unusual vote.

The State Assembly approved the bill the following day, but that wasn’t the end of the fight. That Saturday, over 100,000 people thronged the Capitol, the largest political rally in Madison’s history, and the effort to recall Walker and the politicians who masterminded the legislation began in earnest.

Credit: AP Images

In the weeks after the bill’s approval, opponents of Walker’s anti-union agenda turned their attention to the April 5 Wisconsin Supreme Court election. Incumbent justice David Prosser aligned himself with Walker and the Republican right throughout the fight over the bill, which turned his challenger, Assistant Attorney General JoAnne Kloppenburg, into a champion for Wisconsin’s left.

Though all reports had Kloppenberg in front after ballots closed on April 5, a county clerk and former staffer for Prosser and Walker declared that she had found just the right amount of votes needed to secure victory for Prosser.

Losing the court seat demoralized Wisconsin’s left, and when it came out in July that Prosser had bullied and physically assaulted a fellow judge in a confrontation over Walker’s bill, the defeat was even bitterer.

Credit: AP Images

By the time summer rolled around, the effort to fight back against the senators who had enabled Walker in running rough-shod over legislative procedure was in full swing, with six Republican senators standing recall elections in July and August. The state’s GOP also put three Democratic senators up for recall. While all three of those Democratic senators withstood the recall efforts against them, Democrats overall gained two seats by ousting Republican senators.

Image courtesy of Anne McClintock

Starting on November 15, activists around Wisconsin trudged door-to-door, collecting signatures for petitions to recall Governor Walker, four Republican state senators and the state’s Republican Lieutenant Governor. The effort needed 540,208 valid signatures to recall Walker, and instead collected over 1 million signatures by the January 17 filing date. The Government Accountability Board of Wisconsin is now reviewing the signatures and six weeks after the signatures are verified, Walker will face a recall election.

No one knows exactly how the fight will play out. Walker and Republican governors in other states who followed Walker’s lead will face recalls, referendums, and revolts. In Ohio, where labor led and Democrats followed, the results were spectacular—a 61–39 landslide for labor rights in the November 2011, referendum vote. But there are no guarantees that state-based initiatives will always be so well-focused and successful. But to get a sense of the steps forward for Wisconsin and America’s uprising, look forward to John Nichols’s article in this week’s issue of The Nation.

Erin Schikowski contributed research for this slide show.

Credit: AP Images