Seventeen years ago, as apartheid came to an end in South Africa and a democratically elected government took power, the country became an abortion rights pioneer. In 1996, the post-apartheid legislature passed the first law in sub-Saharan Africa legalizing abortion without restriction in the first trimester, and with a doctor's approval thereafter. The new rules allowed women to walk into a public hospital or clinic, confirm their pregnancy and gestation period, and request and receive a free abortion if they were fewer than thirteen weeks along in their pregnancy. The law "is probably the most progressive [abortion] law in the world," says Jane Harries, director of the Women's Health Research Unit at the University of Cape Town. Yet however liberal the law, sixteen years later, the promise of access "doesn't necessarily translate into services that are available."

Credit: Jake Naughton. Support provided by the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting.

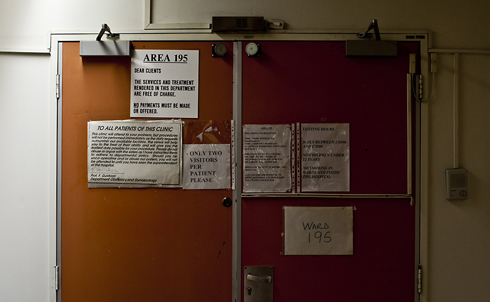

Free abortion is guaranteed at public hospitals and clinics designated by the government to offer the service. Yet less than half of the facilities so designated actually offer the procedure. And that's an improvement over four years ago, when‚ more than a decade after legalization‚ only 25 percent were providing services. That means women run a gauntlet when trying to access services. Clinics are an expensive taxi ride away. Intake procedures meant to streamline high demand mean women have to schedule their procedure and return.

Credit: Jake Naughton.

Mfundo Mabenge, head of obstetrics and gynecology at Port Elizabeth's Dora Nginza hospital, blames the government. "Government has failed us. They compel us to offer a service for termination of pregnancy, but they give us no support." Mabenge, like other ob/gyn chiefs we talked to, was simply told to make space to provide abortions, and then to offer them. The government covers the cost of the procedure, but Mabenge says there's no money to add beds, mop the floors, or otherwise create and maintain a clinic space.

Credit: Jake Naughton.

Public health facilities may perform either first- or second-trimester procedures, depending on the training of their staff. A first-trimester procedure, available without restriction up to twelve weeks of pregnancy, requires midwives trained in either manual vacuum aspiration or medication abortion (or both). The second-trimester procedure is most often surgical and must be performed by a doctor. Second-term procedures are restricted to cases of rape or incest, likely physical or mental harm to the mother or the fetus, or significant impact on the socioeconomic status of the woman ‚ a wide criteria that some midwives say can cover a fear of poverty or a desire to continue education.

Credit: Jake Naughton.

For second-trimester abortions, many women in the Johannesburg area turn to Charlotte Maxeke Johannesburg Academic Hospital. The hospital sees 3,000 women a year and turns two-thirds of them away, usually because they're too far along in their pregnancy (the cut-off for second-trimester procedures is twenty weeks). Norma Bustard, nurse manager at Johannesburg Academic, says women routinely tell her staff that they've waited days at different clinics, across the span of their pregnancies. "Then they came back another day, and the clinic was still full," she says. By the time they make it to Bustard's ward, "this may be their third or fourth clinic."

Credit: Jake Naughton.

Behind most abortions is an unintended pregnancy. Sharon Hobo, a nurse in the Dora Nginza abortion facility, says teens especially have difficulty accessing family planning services. "They say 'My mom doesn't want me to go,' or 'he school hours clash with the clinic hours,'" Hobo says. There's a broad social denial about teens' sexual activity, but there's also stigma. "In the culture, you know [contraception] is a taboo," Hobo says.

Credit: Jake Naughton.

National and international statistics suggest a general pattern of neglect on women's health. The maternal mortality rate in South Africa is up more than 20 percent in as many years, according to the UN Population Fund. Though South Africa boasts one of the continent's most robust economies, and spends more per capita on health than any other country in Africa, its maternal mortality numbers are on par with the Republic of Congo. Even Pakistan is doing better.

Credit: Jake Naughton.

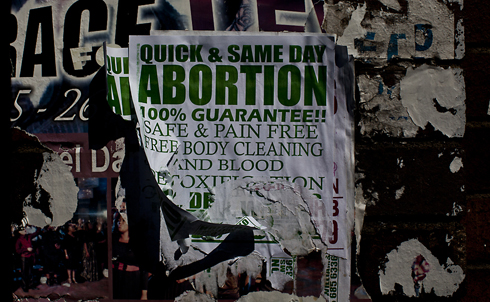

In today's South Africa, it is often easier and cheaper to get an illegal abortion than a legal one. Across the street from the Hillbrow clinic in Johannesburg, a brick apartment building is plastered with neon-colored posters advertising fast, cheap and confidential services. The same posters line the streets of nearby Soweto township; they paper Port Elizabeth's bus depots, roughly 650 miles away on the eastern coast, and they cling to electricity poles in the rural, northernmost province, Limpopo. In short, they're everywhere.

Credit: Jake Naughton.

Like midwives performing abortions, or doctors inducing labor, illegal abortion providers use misoprostol. The drug detaches the fetus from the uterus, which means its safe use depends entirely on the dosage and accompanying medical oversight. Illegal providers simply hand women pills, and the women hope for the best.

For women who've been turned away from clinics ‚ or couldn't get there in the first place‚ back alley providers are a last hope. As Trueman puts it, "When a woman makes a decision she's going to terminate, she's going to terminate." That's especially true for young women. According to the South African Medical Research Council's most recent youth risk behavior survey, in 2008, nearly half of girls ages 13 to 19 who had an abortion did so outside a hospital or clinic.

Credit: Jake Naughton.

One improvement to the abortion situation may be medical abortions. Unlike current procedures, which require several hours in a clinic and a manual "evacuation" of the uterus by trained staff, medical abortion induces termination with a combination of drugs. Women take the first drug at the hospital and the second at home, and they return to the hospital 10 to 14 days later for a checkup. Medical abortions are already an option in the Western and Eastern Cape, and three other provinces are slated to offer that option this year, with help from Ipas. Medical abortion is also a popular choice; in one province, Ipas found that more than 75 percent of women intending to terminate prefer the option.

But South Africa's medical establishment has been wary. "Medical people in South Africa are not very happy about women doing things on their own," says Trueman. "But women are pretty sensible, believe it or not. And they know their bodies."

For more on South Africa's barriers to abortion, read Jina Moore and Estelle Ellis's article, "In South Africa, A Liberal Abortion Law Doesn't Guarantee Access."

Credit: Jake Naughton