Since age 12, Cadeem Gibbs has struggled to reconcile his desire to learn with his incarceration.

Molly Knefel

When he was young, Cadeem Gibbs was really into school. Bright, curious, and naturally rebellious, he enjoyed arguing the opposing point of view in a classroom discussion just to see how well he could do it. “I was always academically inclined,” says the Harlem native, now 24. “I always wanted to learn.”

But there were plenty of stressors in his young life—a violent upbringing, a household in poverty—and the struggle to navigate them pulled him away from his education. He started getting into trouble and ended up in the juvenile justice system at the age of 12. That first contact with “the system” began a 10-year cycle of incarceration that ended only when Gibbs was released from an upstate New York prison two years ago, at the age of 22. He was just a sixth grader when first arrested, but he would never complete a school year as a free child again.

Americans believe that education is the great equalizer, the key that opens the door to a better future and lifts young people out of poverty. And this is true, to an extent—those who finish high school or college have lower unemployment rates and higher incomes than those who don’t. But while people who don’t complete their education are more likely to stay in poverty, they’re also more likely to come from poverty. In the 21st century, so-called reformers have emerged to prescribe everything from charter schools to iPads in order to boost poor students’ educational achievements.

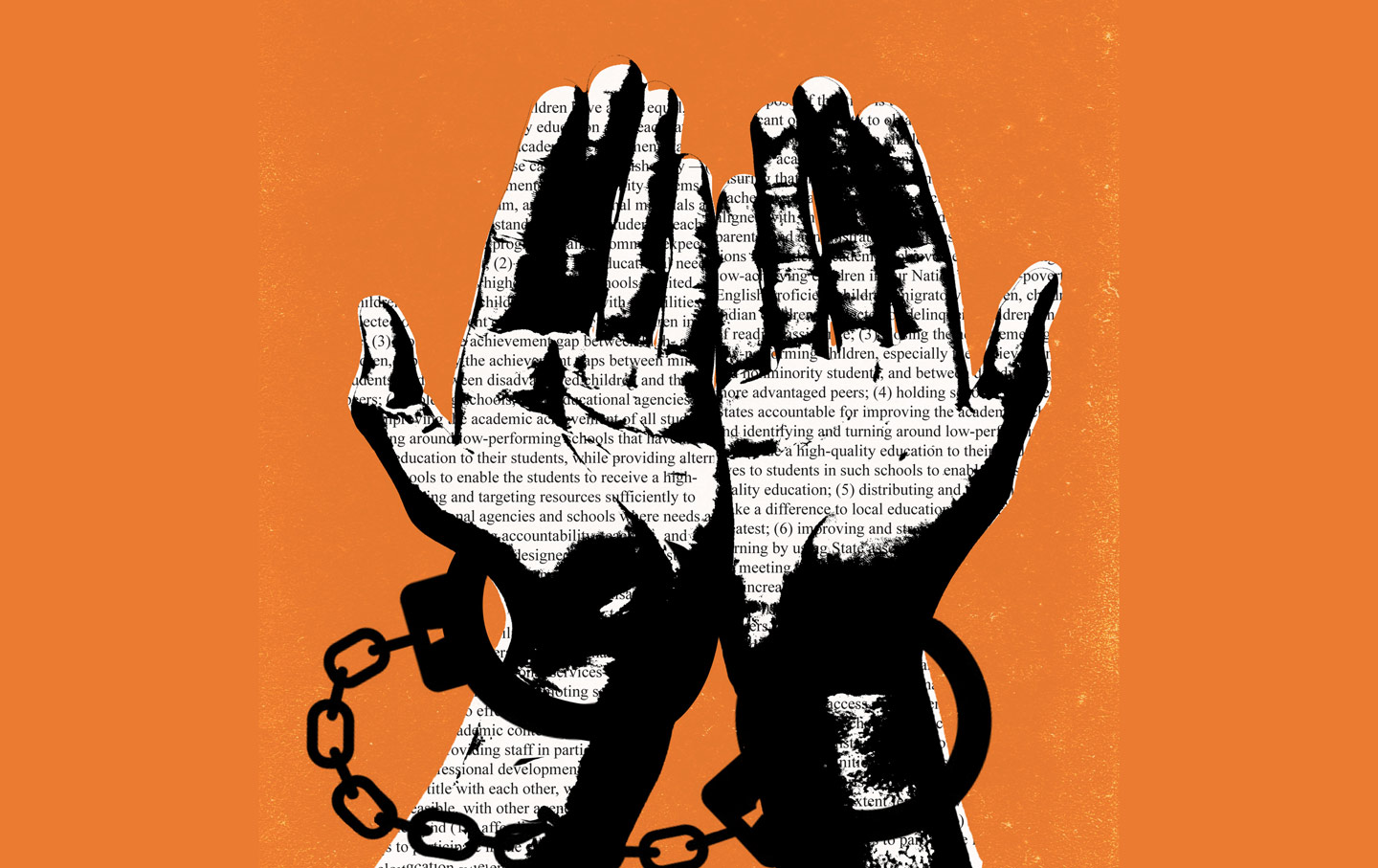

Ignored is a trifecta of policies that prevent young people in poverty from finishing their education: high-stakes testing and the high-stakes discipline that comes with it; weak to nonexistent federal policy concerning education for those young people already involved with the juvenile justice system; and a lifetime of background checks that keep the formerly incarcerated from gaining degrees and finding jobs.

These intersecting policies, which push kids out of school and into a punitive legal system, are collectively known as the “school-to-prison pipeline.” But the individuals who emerge at the end of that pipeline, though criminalized, are still young people—a population that has a reasonable expectation to receive an education. So what happens to a young person’s schooling when he or she is taken out of the classroom and put behind bars?

For poor students of color, like Gibbs, the problems can begin early. These children were the target of George W. Bush’s No Child Left Behind law, which was passed in 2002. The law mandated 100 percent student proficiency in math and reading by 2014. Schools that failed to make adequate yearly progress faced a set of sanctions ranging from staff firings and restructuring the school, to turning it into a charter school or handing it over to private management. Terrified of missing the NCLB guidelines, schools got rid of students who might hold back their numbers. Suspensions, expulsions, and school-based arrests skyrocketed in the wake of the new law, pushing hundreds of thousands of students out of school and, frequently, into the justice system. Such policies disproportionately affect students of color and students with disabilities—compared with their white peers, black youths are three and a half times more likely to be expelled and, if arrested, nine times more likely to receive an adult prison sentence. Even though overall youth crime has decreased since 1999, youth punishment has not: From 1999 to 2008, the number of total youth arrests fell more than 15 percent, while the number of juvenile-court cases remained virtually the same, falling only 4 percent. This means that while fewer young people are getting arrested, they continue to be processed through the system at the same high rates.

When Gibbs was arrested for firearm possession at school, he spent time in both secure and nonsecure facilities while attending his court dates. He then landed in an “alternatives to incarceration” program at Children’s Village, spending a year there. A residential campus in Dobbs Ferry, New York, 35 minutes outside of New York City, Children’s Village serves young people from both the juvenile-justice and child-welfare systems. Although the staff acted kindly toward him, Gibbs says he felt discouraged and resentful. He was placed in a special-education class, which made him feel like there was something wrong with him. He had weekly counseling sessions, which he hated; he says he would go into each session and sit in complete silence while the social worker asked him questions about his life, refusing to say a single word for the entire hour. It’s only now, in retrospect, that he realizes that his silence came from a lack of trust. “I didn’t know I didn’t trust her,” Gibbs says. “I just thought I didn’t want to be bothered. I was angry. I didn’t want to be there.”

When he was released from that placement and tried to reenter the regular school system, Gibbs hit a number of barriers. Because it was near the end of the school year, he had to finish middle school at Children’s Village, taking a 45-minute bus ride from his home in Harlem to Dobbs Ferry every day. Even so, he was behind in credits from all the classes he’d missed while in custody, and it was time for him to start high school. “It took me a while to find a school,” he says. “No school would accept me.” He ended up at an alternative high school serving young people who had been suspended, expelled, or otherwise pushed out of their community schools.

This type of barrier to reentry is a common one for young people hoping to return to their schools after a juvenile placement. The high-stakes testing standards under No Child Left Behind prompt schools to exclude students coming from the juvenile-justice system. Because those students are likely to have fallen behind academically, their potential for scoring poorly on tests becomes a liability, creating a perverse incentive structure in which it’s better to exclude high-needs students than it is to educate them. School districts can refuse to accept the partial credits earned during the time a child spent in custody—and they can also refuse to re-enroll that student entirely.

Even for those who do get a meaningful education inside the system, the trauma of being detained can have a long-lasting effect on young people, who are still developing in crucial ways. “It’s life-changing—any contact is impactful,” says Elijah Tax-Berman, a high-school social worker at a New York City network of schools that serve young people involved with the juvenile- or criminal-justice system, as well those who are homeless or in foster care. Some of the schools in which Tax-Berman works have installed metal detectors, and he says that some students have stopped attending school because of the indignities associated with the search process. “It may seem like a little thing: ‘Take the wrappers out of your pockets, turn in your cellphone, take off your belt.’ But they’ve had such a negative experience, they’re so uncomfortable with it, that they stop coming to school.” For those students, the metal detectors at the front door act as a literal barrier to entry.

* * *

“A lot of kids go into juvenile-justice facilities, and that’s the end of their education,” notes Jessica Feierman, supervising attorney at the Juvenile Law Center in Philadelphia. Underlying this problem is a patchwork of dysfunctional local policies. “There is a huge degree of variability as to what happens to a young person, depending on what state they’re in or even what part of the state they’re in.” In some states, the youth agency that administers juvenile justice—in other words, the system itself—is also responsible for education. In other states, the responsibility is not in the hands of the state agency, but the local or county school district. “We found that both of those systems have some structural challenges,” says David Domenici, founding principal of the Maya Angelou Academy, the school inside Washington, DC’s, long-term juvenile facility. When school districts are in charge, juvenile inmates may not be a top priority for superintendents, who are busy overseeing all the schools in their district and ensuring that each is making yearly progress in the high-stakes education climate of No Child Left Behind. And when juvenile-justice agencies are in charge, Domenici adds, many of the facilities were set up decades ago as part of a “lock ‘em up” correctional approach in which school was also not a top priority. Then, “as an afterthought, people started to think, ‘Oh my gosh, we’re responsible for educating these people.’”

Being held in the custody of the juvenile-justice system can take a number of forms, from nonsecure residential placements (some of which are meant to resemble a homelike setting) to secure correctional facilities, or “lockup” for children. Only half of the young people in residential placements around the country reported having “good” education programs at their facilities, and less than half (45 percent) spent a full school day (at least six hours) receiving instruction. Those numbers come from the Department of Justice; its Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention surveys young people in residential placements across the country to assess their needs and the services they receive. The same survey found that a third of the young people in custody had a diagnosed learning disability. That’s seven times the rate of the general public-school population—and less than half were receiving the special-education services they have a legal right to. A stunning 70 percent of the young people had, like Gibbs, experienced some kind of trauma at some point in their lives.

And while a school schedule may operate on semesters or trimesters, juvenile placements do not—adding yet another logistical challenge not only for system-involved students, but for educators. “Kids come in and out a lot,” Domenici explains. Again like Gibbs, children are often transferred between several facilities before landing in a long-term placement, by which point they’ve missed weeks or even months of school. “And everyone just says, ‘Well, everyone in the whole District of Columbia is supposed to be on page 89 of their algebra book and chapter 16 of their humanities book,’” Domenici notes. That’s an unrealistic approach for any student, but especially those who have already had negative experiences in school. “I’m a very big fan of increased expectations for kids—but for kids who have been totally disengaged, we need to find a way to get them reengaged.”

To that end, Domenici has purposefully designed his school’s curriculum around themes that relate to their experience—relationships, change, choice, power, and justice. The academic year is broken up into eight units, and each unit has 22 days of instruction. Students earn credits for each completed unit, which means that even if they’re released in the middle of the school year, they leave with the credits they’ve accumulated during their time there.

It’s a simple solution to what Domenici describes as a set of deeply structural and philosophical problems regarding how to educate young people in the juvenile justice system. Beyond immediate trauma, system-involved young people often have other factors in their lives that prevent education from being the door-opener it’s understood to be. Obtaining a degree is hardly a guarantee of financial security for any young person, much less one who is living in poverty. “Our young people struggle with its relevancy,” says Tax-Berman. ”I struggle with them struggling with its relevancy. I can’t stand here and say, ‘You need to do well in school and everything will be OK,’ because it’s not [true]. You need to feed your family.”

According to Gibbs, that’s exactly why he kept winding up back in the system: The external circumstances of his life hadn’t changed. Not long after entering his alternative high school, he got into trouble again and was sent back to Children’s Village. When he got out the second time, it took him several months to find another school. He started at a regular city high school after the academic year had already begun, was expelled before the semester was over, and was arrested shortly after being expelled. By that time, he was 16 and an adult in the eyes of New York—the only state besides North Carolina that still prosecutes all 16-year-olds as adults. That meant he was headed to Rikers Island.

“It was terrifying because I was young, and I was around people much older than I was,” says Gibbs, who explains that even though youths under 18 are housed separately, they are frequently exposed to the adult population in common areas. “It’s like maybe [adult prisoners] might prey on me—and not even only that, but the corrections officers too.” Gibbs did feel targeted by the guards and other prisoners, but he did his best to cope and, upon his release, earned a GED on his own. At 17, Gibbs was arrested again on a drug charge and sent back to Rikers. He says he expressed interest in attending school while he was there, but was prohibited from doing so because he already had his GED.

In December 2014, the Justice Department and the Department of Education issued federal guidelines regarding correctional education in juvenile-justice facilities, outlining some of the key issues that the country’s 60,000 children in custody face in continuing their schooling. The extensive package addresses the educational and civil rights of students during their incarceration and through their transition back into the community. It’s “a critical step in helping increase access to education for young people involved in the juvenile-justice system,” says Jenny Collier, a project consultant for the Robert F. Kennedy Juvenile Justice Collaborative. A number of the guidelines reflect the struggles of young people like Gibbs; they include raising academic standards for those in custody and implementing more rigorous reentry programs to support those students as they return to their community schools.

But there’s an even bigger issue to address than those massive systemic obstacles, says Domenici: “There’s a big philosophical problem here. There clearly are a lot of people in youth facilities who want these kids to be successful and who believe in them. But there are plenty of people who believe that these are kids who have stolen cars, beat people up, chronically steal, whatever—and [that they] just don’t deserve to be in a great school.” This all-too-common way of looking at the issue prevents stakeholders from approaching the education of young people in juvenile facilities with the financial, organizational, and personal investment necessary to make it a meaningful experience.

* * *

Even if a system-involved young person manages to navigate these institutional barriers and external factors and succeeds in getting a degree, he or she will still face tremendous obstacles. Dina Sarver, a married mother of two in Florida, was arrested on three counts of grand theft auto when she was 15 and sent to a residential facility. The placement was a truly rehabilitative setting focused on pregnant teenagers, and Sarver says that it gave her the resources and support to get her life on track. After being discharged, she earned a high-school diploma and was accepted into an associate-degree program for registered nursing, where she hoped to become a nurse practitioner. At her second orientation, she asked the department manager about background checks and was told that a juvenile felony record was an automatic disqualification from the program. Sarver went on to complete a bachelor’s degree in healthcare management, but her final class required an internship, and that called for a background check. Only with the help of two public defenders who advocated on her behalf was she able to graduate.

Sarver is now 23. In Florida, most juvenile records are expunged when the offender turns 24 or 26, depending on conviction history and the offense. Until then, her record is available to any potential employer. Even after that, employers in certain fields, like those involving children, the disabled, and the elderly, still have a right to her expunged record. This is devastating for Sarver, who still wants to work in healthcare. “All these doors are closing in your face, and you don’t know what to do,” she says. “And sometimes it’s discouraging, because here you are, trying to do everything you can to become a productive member of society. I’m trying to get my education, become a better person, become a better mom, and I can’t do that because I’m so confined.” She can’t even go on her son’s field trips, because the school district runs a check on chaperones.

Cadeem Gibbs’s carceral experience culminated in a sentence served in an upstate New York prison, where he finally had access to books, magazines, and high-quality college courses. It was the most engaging educational experience he’d had since entering the system. He completed a human-services certificate program, maintained a high grade-point average, and accumulated a number of credits. When he was released last year, he enrolled at a community college—only to find out, once again, that many of the credits he’d earned didn’t transfer. “And I guess I’m at the point now where I don’t want to pursue a formal education. I’ve been kind of turned off by it,” he says. Instead, he’s been focusing on youth advocacy, such as the Raise the Age campaign fighting to change the state law that treats 16- and 17-year-olds like adults. He also works as a consultant for the Washington, DC–based Children’s Defense Fund. He remains passionate about education, but fears that spending more time and money on school won’t get him closer to his dreams, especially given his record.

“Things as menial as stockroom positions present challenges to you if you have a conviction,” he says. “So they kind of paint you into a corner—they tell you they want you to be militant and do all this time, and you come out and there’s limitations on the things that you can do.” Gibbs’s record can affect his ability to obtain public housing—even private housing if the landlord runs a background check. “The irony is, I still have to provide for myself,” he says. “So if I can’t have access to all these things, what am I supposed to do?”

Although he’s been doing well since his release, Gibbs worries about other people in the same position. “The uniqueness about me is that I kind of defied the odds and all that. Which is cool—it’s a great story,” he says. “But that shouldn’t have to be the case, because not everyone is going to think like me and navigate these obstacles.” Stories about those who have defied the odds, he thinks, leave out the vast majority of people who continue to be marginalized. “You’re talking about the lion’s share of the population that experiences this,” he adds. “This is what the day-to-day adversity is.”

The equalizing potential of education relies on the premise that it can open doors for every child who has access to it. But where does that leave the children whose lives consist not of open doors, but of locked ones?

Molly KnefelMolly Knefel is a journalist, writer and co-host of the daily political podcast Radio Dispatch. She also teaches after-school at an elementary school in the Bronx.