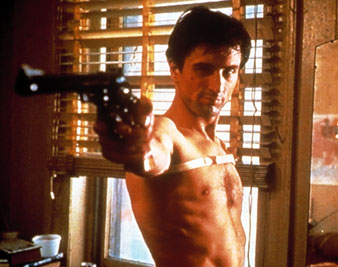

Everett CollectionRobert DeNiro in Taxi Driver, 1976

Everett CollectionRobert DeNiro in Taxi Driver, 1976

John Hinckley ignored Robert DeNiro and became obsessed with Jodie Foster, eventually attempting to kill President Reagan to impress her.

Taxi Driver is not about driving a taxi; it is about loneliness in the big city (New York) and the melancholy of unfound identity— real, if also fashionable, maladies. Martin Scorsese (screenplay by Paul Schrader) employs a cabbie to explore the subject because his trade puts a cabbie in touch with a great many people, but introduces him to none. It is a fault of the big city that there are many such jobs. Scorsese uses a taxi driver also because the wanderings of a cab through the main avenues and scabrous neighborhoods of New York provide occasions for the verismo photography and surreal camera effects that delight him. The signature of this picture is the fragmentation of neon-bedecked canyons through a rain-obscured windshield.

Finally, Scorsese has cast Robert De Niro in the title role, because the picture will advance into the area of psychosis and De Niro, as he demonstrated in Mean Streets, is adept at a kind of smiling nuttiness that would make any observant bystander seek safer company. The hiring boss at the taxi garage is not observant, and that is why Travis Bickle (De Niro) finds himself at the wheel of a cab. You and I would hope to spot the lethal component in his goofy smirking and not trust him with a handcart.

So, with the fuse lit, Scorsese sets the traffic swirling and the horns blaring, picking up the beauty of the city and the squalor, and pounding away with a musical background so painfully loud that I had to peer beneath its physical pressure to follow what was going on. It wasn’t hard to see that Travis, what with long night hours on the streets, alternately popping pills and swigging from a half-pint bottle, was rapidly losing whatever grasp he had once had on reality. He has seen an ample blonde (Cybill Shepherd) in the window of a political campaign headquarters, manages (to my astonishment) to get her out for a coffee break, assures her that he sensed at once there was “something” between them and on their first real date takes her to a hard porn Times Square movie, from which she flees in a rage, leaving him more alone than ever.

Travis keeps a diary and writes long fantasy-embroidered letters to his parents— stock symptoms, the biographies of recent assassins have taught as, of paranoia flowering in solitude. He buys guns, a ‘whole arsenal of them, invents ingenious ways of hanging them about his person, works hard to get himself in fighting trim and—gasps from the audience—appears one day with his head shaven to an Indian war tuft. Travis has been complaining for some time, ‘to fellow drivers and casual, fares, that the city is a sewer, so now comes an avenging angel bout of pimp slaying in Harlem, which greatly relieves the troubled ‘young man’s emotional tension, restoring him to his habitual state of unfocused good humor, but leaving me with the impression that my intelligence had been insulted.

De Niro is a good actor: he “feels” exactly like a cabbie, which is something a lot of actors could do, since getting into the skin of a job is a knack at which American actors excel. But De Niro does something a good deal more difficult—he simulates insanity at just the level that will get by as no more than eccentric among colleagues and passers-by. Accordingly, one observes his disintegration in a mood of fatalistic depression—the outcome is only too inevitable. And ‘yet, for me at least, the picture did not work.

That is because Scorsese tries by main force to make it work. He has real and terrible subject matter (though the thinnest of stories)—the incipient mania that is inflamed by the impersonality of a big city and goes unnoticed amid the distractions of a big city. Unless you begin to walk funny or take to addressing large imaginary audiences, you can readily get to the cleansing blood-bath stage without setting off the alarms,(see the six o’clock news almost any week). But Scorsese seems to have thought that this somber fact could best be put on the screen not by developing character but by turning all the resources of contemporary cinematography up to their highest pitch. Travis Bickle’s trouble was that he couldn’t get close to anyone, but Robert De Niro’s trouble is that he can’t get past the audio-visual pandemonium to show you Bickle’s torment from inside. In the end, all you have is a shudder, from the six o’clock news. I don’t see much gain from spending two hours at a movie which celebrates the horror of anonymity by employing every mechanical means to keep its hero anonymous. De Niro did what he could to break through but he couldn’t fight the production. Stunning is the word for it.