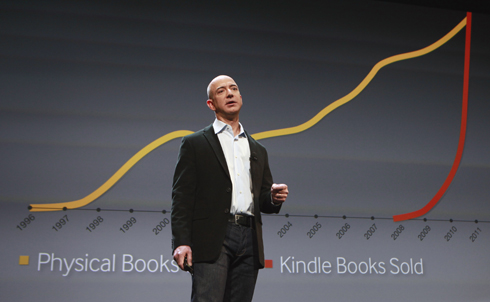

Even with Borders gone and independent booksellers struggling to get by, the war for the future of publishing rages on. As Steve Wasserman explains in “The Amazon Effect,” which appears in this week’s special issue of The Nation, booksellers and publishers have shifted toward digital books, and Amazon.com, which sells more electronic Kindle books than physical hardcovers, is well positioned to overpower its rivals. But what’s at stake in the battle over e-commerce and why should you avoid doing business with Amazon.com?

Last year, the Greenlining Institute reported that Amazon’s tax rate was among the lowest, at just 3.5 percent, of all companies included in the study. Yet despite the massive savings Amazon enjoys from exploiting tax loopholes, the company contributes surprisingly little to charities around its Seattle-area headquarters.

AP Photo/Mark Lennihan

Amazon is the world’s largest bookseller, offering more than 2 million titles. In an effort to lower prices, the company has demanded additional discounts from distributors—which, as Colin Robinson points out, is illegal under anti-trust law that prevents companies from selling a product at different prices to different customers. The company has been accused of having a “monopolistic grip on the publishing industry.”

AP Photo/Mary Altaffer

Amazon offers bestsellers at a loss in order to attract customers, a practice that has upended traditional publishing in the United States. But it doesn’t have to be this way, as Germany’s bookselling model illustrates.

Photograph: Anite Lillie

Amazon.com states that it is “not in the business of selling” customers’ private information—e.g., what you buy, what you review, how you browse—to other companies, but last year Amazon.com was embroiled in a class-action lawsuit (Del Vecchio et al. v. Amazon.com) for allegedly bypassing customers’ privacy settings. Others have raised concerns about Kindle Fire’s web browser, fearing it would allow the company “to track customer behavior all over the Web, gathering data and marketing intelligence as it goes,” according to the New York Times.

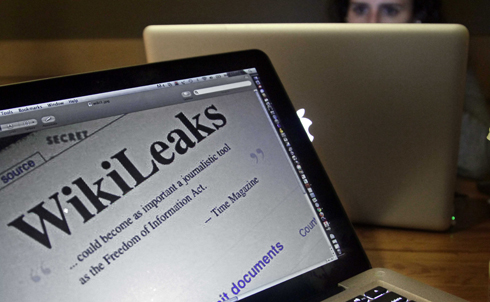

Reuters/Brian Snyder

Under political pressure, Amazon removed WikiLeaks from its cloud server in 2010, prompting this question from Keir Thomas of PC World: “In an idyllic future where we make heavy use of the cloud, what happens if a cloud service provider removes content it deems inappropriate, or just doesn’t like?”

AP Photo/Bebeto Matthews

Amazon was late to pull out of the American Legislative Exchange Council, a conservative, pro-business nonprofit that recently came under fire for helping spread voter-identification and “Stand Your Ground” laws. Amazon, which has fought state-level taxation, focused on tax laws in ALEC.

Reuters/Jim Young

When the Communications Workers of America launched a campaign to unionize Amazon’s customer-service representatives, the company argued that “unions actively foster distrust toward supervisors” and “create an uncooperative attitude among associates by leading them to think they are ‘untouchable’ with a union,” according to the New York Times. To make matters worse, many Amazon employees are temporary workers who do not receive basic benefits like healthcare, and for whom forming a union is “virtually impossible.”

AP Photo/Ross D. Franklin

Working conditions at Amazon.com warehouses can be brutal. Last fall, the Morning Call reported that employees were being “pushed to work at a pace many could not sustain” in warehouses where the temperature exceeded 100 degrees, causing workers to feel light-headed and pass out.

AP Photo/Scott Sady

Amazon has made searching easier and more efficient, providing free information about books and, in some cases, permitting readers to “look inside” them. However, as Anthony Grafton explains in “Search Gets Lost,” the company has gradually cut back on its search capabilities, instead inviting the customer to provide information of every sort for Amazon to digest and profit from.

In 2011, Amazon’s $48 billion in revenue exceeded that of all six major publishing conglomerates combined. It now resembles an “online Walmart” rather than a bookseller, writes Steve Wasserman, and has begun to colonize movie, baby product and shoe retailer websites, as well as the high-end fashion industry. For more on Amazon’s outsized power, be sure to read all of the articles in this week’s special issue on the retail giant.

The Amazon Effect, Steve Wasserman

How Germany Keeps Amazon at Bay and Literary Culture Alive, Michael Naumann

Search Gets Lost, Anthony Grafton

Reuters/Shannon Stapleton