Earlier this week, Attorney General Eric Holder declared in his address to the NAACP national convention in Houston what many voting rights advocates had been saying for months: that the photo voter ID law passed in Texas is a poll tax. Determining whether voter ID laws are as unconstitutional as poll taxes won’t be up to him, though. That honor goes to the US Supreme Court justices who lately have been signaling they may be ready to gut the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

What this means is that a legal challenge to a voter ID law in Texas could be the trigger for the demise of the constitutional act that made it possible for people of color to vote in much of the country. Right-wing pundits have all but conceded this week’s US District Court hearing over Texas’ voter ID law to the Department of Justice. There’s agreement on the left and the right that Texas didn’t do a good enough job proving that the law has no discriminatory purpose nor effect. Experts have testified that almost 1.4 million Texans could be disenfranchised due to lacking ID.

The state’s argument wasn’t helped by Texas state Senator Tommy Williams, an author of the voter ID law, who said, “I think people who live in west Texas are accustomed to driving long distances for routine tasks,” when confronted with the fact that the closest DMV for some low-income Texans could be dozens of miles away.

None of this may matter, though. If the district court judges rule that Texas’ law should not be cleared by DOJ, then that could set it up for a fast-track hearing before the Supreme Court. And the Court has indicated that it is ready to throw Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act—the part that gives DOJ preclearance authority over Texas’ election laws—out altogether, which would trigger a rollback of voting rights expansions made since the civil rights movement. There is little optimism that Chief Justice John Roberts will do for VRA what he did for the Affordable Care Act. Section 5 is to the VRA what the individual mandate is to ACA, but Roberts has little sympathy for laws that remedy histories of racial discrimination.

Duke University election law professor Neil Siegel told Politico, “He’s a deeply committed conservative on matters of race. On the challenge to the Voting Rights Act, he’s warned Congress we’ll strike it down if you don’t change it.”

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

If the Roberts Court overturned VRA, it would be a grand departure from the SCOTUS decision of 1944, Smith v. Allwright, which helped launch the movement toward civil rights and voting justice for all Americans. That 1944 case involved an African-American man named Lonnie E. Smith who challenged the Texas Democratic Party, which forbade anyone except white people from voting in its primaries. Since Texas at the time was a one-party, Democrat-ruled state, the primaries determined who would win its general elections, guaranteeing black Texans would have no say in who would represent them in government.

Smith v. Allwright was argued by Thurgood Marshall, who considered it his most important case. When the Supreme Court ruled in favor of Smith, it was considered a turning point in the burgeoning civil rights movement. Marshall called it “a giant milestone in the progress of Negro Americans toward full citizenship.” The victory led to an emboldened black electorate and surges in NAACP membership throughout the South—surges that provided the NAACP with the resources to win more voting rights and civil rights battles in court, all the way through to the Brown v. Board of Education victory ten years later and the passage of the Voting Rights Act roughly ten years after that.

A fully nourished NAACP legal team was needed in the years after Smith v. Allwright, mostly because that decision didn’t automatically grant easy, fair access to the vote, in Texas or anywhere else. That 1944 decision actually led to a proliferation of new poll tax requirements throughout the South that placed typically insurmountable barriers in front of black people seeking to vote.

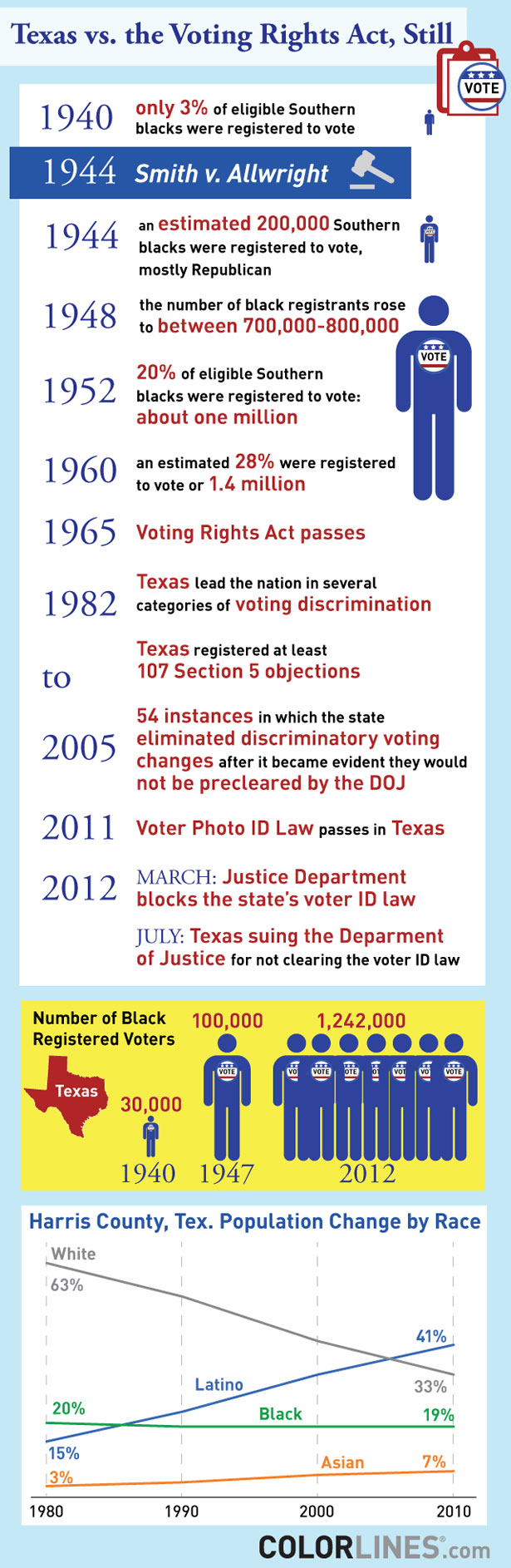

Still, the number of African-Americans registered to vote after Smith v. Allwright expanded significantly—Southern black registration quadrupled between 1940 and 1947, from 3 percent to 12 percent, and from 30,000 to 100,000 in Texas in the same time period—and this is exactly what drove segregationists to continue launching poll tax deterrents and other attacks (like Ku Klux Klan terrorism). Southern whites didn’t want black people voting because they feared they would lose political power.

This was laid bare when Mississippi Sen. Theodore Bilbo, in protest of a law to ban poll taxes, said, “If the poll tax bill passes, the next step will be an effort to remove the registration qualification, the educational qualification of Negroes. If that is done we will have no way of preventing the Negroes from voting.”

When the Voting Rights Act finally passed in 1965, made possible by the Smith v. Allwright decision twenty years earlier, it once and for all banned any instrument, law or policy that would prevent anyone from voting based on race or color. Texas has been fighting back ever since.

When Texas was designated as a Section 5 state due to discrimination against Latinos, it grew increasingly defiant of the Voting Rights Act. According to a report by the Mexican-American Legal Defense and Education Fund, “Voting Rights in Texas 1982–2006,” only one state challenged Section 5 in court more than the Texas in that period—and that’s Mississippi. From 1982 to 2006, Texas registered at least 107 Section 5 objections. Meanwhile, during that same time period, Texas lead the nation in several categories of voting discrimination, including Section 5 violations. Further, from the MALDEF report:

Texas had far more Section 5 withdrawals, following the DOJ’s request for information to clarify the impact of a proposed voting change, than any other jurisdiction during the 1982-2005 time period. These withdrawals include at least 54 instances in which the state eliminated discriminatory voting changes after it became evident they would not be precleared by the DOJ.

In other words, at least fifty-four times in twenty-five years, Texas had to back down from an effort to restrict the vote—thanks to the power granted the federal government under the Voting Rights Act. That power may soon be removed by the Roberts Court.

The VRA enforcement represents an imposition of the federal government on state sovereignty, according to many Texas state officials today. Governor Rick Perry said that DOJ’s enforcement of VRA in South Carolina, for instance, represented a “war” on states’ rights. The current state attorney general, Greg Abbott, has sued the federal government twenty-four times since he took office in 2004 over a number of federal law enforcement measures, not limited to voting rights.

But the same fear of expanding the electorate to people of color that existed in the years after Smith v. Allwright seems to have spurred Texas state legislators to create the voter ID law currently challenged in court. During this week’s district court hearing, voting rights and race expert Morgan Kousser, of California Institute of Technology, testified that “there was considerable concern” among white state legislators about “losing control” of the legislature. “There is such a correlation between partisanship and race that any bill that has partisan effects would have racial effects,” said Kousser.

In Harris County, where Lonnie E. Smith first challenged the all-white right to vote, the expansion of the non-white electorate shows a clear political power shift. In 2008, Barack Obama won the county, the first Democrat to do that since Lyndon B. Johnson in 1964. Johnson, of course, went on to sign the Voting Rights Act into law the following year. Meanwhile, whites who were the majority in that county in the 1980s, are today the minority, representing only a third of the county’s population. Harris County encompasses Houston.

It’s population shifts like this that led to redistricting wars in Texas this year, also fought along VRA terms in federal courts, and to what looks like an agenda to keep political power in white hands. This is the lens through which DOJ and civil rights advocates are viewing the voter ID law, which according to the state’s own data would exclude as many as 600,000 Latinos who are eligible to vote but lack the ID now required. While Texas is offering to issue voting ID cards for free, the documents needed to obtain that ID are not free. Birth certificates and other documents needed for the ID cost upwards of $20 and that doesn’t figure in the transportation costs of those who’d have to travel twenty, thirty or forty miles to a DMV office to get the ID. That amounts to a poll tax, and no doubt Holder had Smith v. Allwright in mind when he made that declaration.

—Brentin Mock

The following infographic was published with Brentin Mock’s July 12 article, “Texas’ Road To Victory in Its Decades-Long Fight Against Voting Rights.”