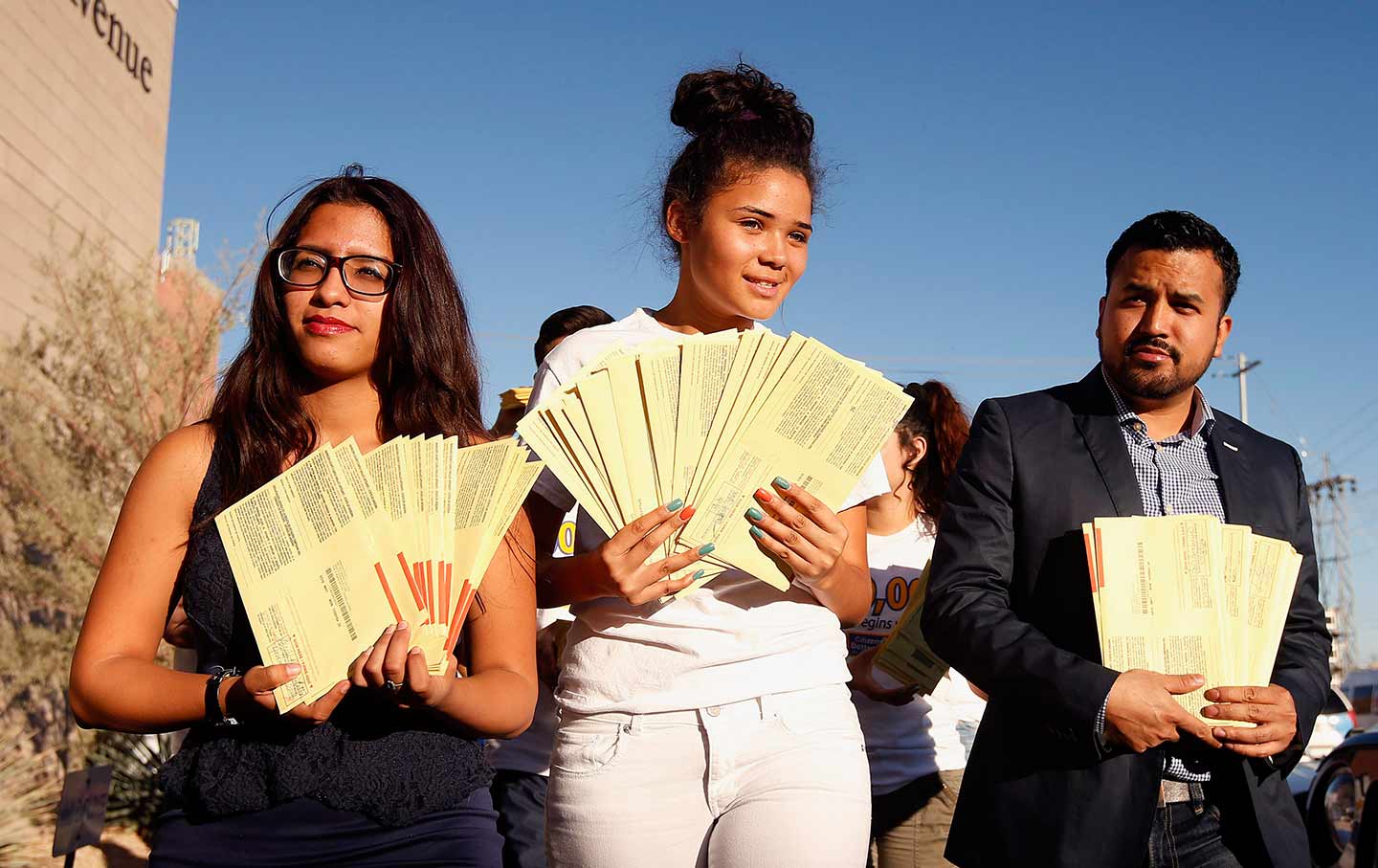

From left to right, volunteers Ariana Calderon, Britany Davis, and Ramiro Luna, the Field Director for Citizens For A Better Arizona join about a dozen others as they drop off nearly 300 ballots at the Maricopa County Recorder/Elections Office Tuesday, November 4, 2014, in Phoenix. (AP Photo / Ross D. Franklin)

Ordinary working people, especially the young and people of color, have been so much and for so long exploited in Arizona that, for many, labor and political activism have become lifelong governing passions, not just a matter of phone-banking on a weekend or two in an election season. Their long misfortunes have galvanized labor into becoming a voter-registration powerhouse and a formidable organizer in the fielding, grooming, and election of candidates. In this way, union activists are achieving tangible results that are improving the lives of all Arizona citizens.

This feature was supported by the journalism nonprofit Capital & Main.

Latinos comprise a 31 percent—and growing—share of the state’s population; it’s long been remarked that the demographics make electoral change here inevitable. But the speed of Arizona’s apparent political shift is owing in no small part to the hard work of a committed labor movement.

Maria Madrid, who works as a maid at the Tempe Mission Palms Hotel, symbolizes the impact of that movement in the Grand Canyon State. The 56-year-old Mexican native describes the new union contract she helped fight for in terms of bloodied knees. Madrid went to lunch one day and discovered that the surgical incisions from her recent knee replacement surgery had burst, and blood was sticking her trousers to her skin. Madrid’s supervisor made light of her injuries. Being provided by management with long-handled scrub brushes for cleaning floors may not sound like such a big deal—until your knees are shot from years of scrubbing tile floors by hand.

“They used never to give us a raise of more than 15 or 20 cents, but now we see the difference in our checks, too,” Madrid told me during a visit to UNITE HERE Local 631 in Phoenix; the hospitality union helped organize the Tempe Mission Palms Hotel last year, staging a two-day vigil and fast in 115-degree heat. Maids at the hotel used to be required to clean as many as 17 check-outs in one day; today the maximum number is 12, Madrid said. “Our insurance rates will be lowered in November. The gains are huge.” Madrid, a grandmother, is studying now to become an American citizen. She is eager to continue to work to bring others into the union, and to persuade more Arizonans to vote.

As Rachel Sulkes, an organizer at the labor-affiliated Central Arizonans for a Sustainable Economy (CASE) and UNITE HERE explained: “While people don’t always understand unions, they do understand organizations that take on bullies in the community, and issues that they’re very passionate about.”

Arizona currently ranks dead last in the nation, by some measures, for state spending on higher education; appropriations have been cut 27 percent from 2011 levels. In Maricopa County, which is home to Phoenix and to Arizona State University, Sheriff Joe Arpaio has been accused of engaging in inmate abuse, deportations, and racial profiling, leading to the recently announced federal prosecution for contempt of court relating to the racial profiling of Latinos.

Many viewed state Senate Bill 1070, Arizona’s infamous anti-immigrant “show your papers” law as an attempt to take Arpaio’s methods statewide. Signed into law in 2010 by then-Governor Jan Brewer, SB 1070 would have permitted law enforcement to demand papers proving citizenship or the right to legal residence of anyone they suspected of being in the country illegally. The bill was produced by the far-right American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), and sponsored by former state senator Russell Pearce. The connections between Pearce, ALEC and the private prison industry, which would have earned millions by jailing undocumented Arizonans, were reported by NPR shortly after the bill’s passage.

After years of litigation, what was left of the unpopular law was recently defanged in a settlement between the state and the American Civil Liberties Union and other civil rights organizations. The reaction against SB 1070 provided the fulcrum on which the state’s political mood finally pivoted, according to U.S. Congressman Ruben Gallego, a Marine Corps veteran of the Iraq War and Harvard graduate, who entered the Arizona State House in 2011.

“SB 1070 kicked off a generational change in terms of Latino leaders,” he told me. “Even if we were going to punch and lose, we had to push back. We were so weak that we were being preyed upon. People did it just to keep their sanity. But being willing to fight was part of the victory.”

Gallego added: “There was a core group of probably 20 Latinos and Latinas and allies who decided they were going to fight back… Now they are working in 501(c)(4)s, the school boards, the statehouse. Arizona [had been] abandoned by national groups. Now that we’re competitive, people are starting to invest [politically] in Arizona.”

I spent some hours in Phoenix with Sulkes, who explained labor’s role in local political activism, and introduced me to some key players. One Arizona, a coalition of 14 grassroots organizations, including CASE, has helped to register 150,000 new voters in this cycle—double its original target, and a substantial share of the approximately 2.3 million votes typically cast here in a presidential election. Student organizations, conservationists, churches and immigration reformers have joined labor in One Arizona to create an explosive increase in civic participation. Their template of five years’ efforts in developing collaborations between activist groups, identifying and securing joint funding, and establishing effective data analysis and leadership development ladders, is there ready and waiting to be exported to other states.

Sulkes is a New England transplant and the mom of two young girls. She is very fair, with pale blue eyes—a confidence-inspiring, quick-witted, fast-talking lady, whether in English or in her elegantly phrased, heavily accented Spanish.

“Our state was sort of the vanguard of the ALEC legislation machine; SB 1070 went to the Supreme Court,” she told me, going on to speculate that the state’s politics were irrevocably altered as the law’s profound effects on citizens began to sink in. “It really felt like this line being drawn in the sand.”

Russell Pearce, she explained, was driven out of office in 2011, and out of his position as the first vice chairman of the state GOP in 2014. (A public outcry following his call for the forced sterilization of poor women as a condition of receiving Medicaid ended in his resignation from the latter position.) “There was a triumvirate that was Pearce, Arpaio and Andy Thomas, the Maricopa County Attorney,” Sulkes said. “Thomas has been disbarred. You could see: It is possible to take this on. Resistance to it was a conclusive success, and that is inspiring to people.”

She introduced me to Betty Guardado, the secretary-treasurer of Local 631, who brought her husband and their baby boy with them. Once a housekeeper at the Century Plaza Hotel in Los Angeles, Betty is a charming, bespectacled woman who wore a sapphire-blue top and who radiates the brains and drive of a trailblazer. She rose year by year, canvassing for Gray Davis in 1998, eventually leading her own team in that gubernatorial campaign, and then another, and another. In the summer of 1999, her union asked her to take a six months’ leave from her hotel job to help organize the New Otani, a hotel they’d been working on for many years. “Those housekeepers are so negative and they need someone young, someone like you. We really want to train you.” It was then that Guardado decided, “All right, if I’m going to commit to this, I’m going to commit to it for the long term.” But the New Otani campaign failed. The hotel was sold in 2007—it’s now the Doubletree by Hilton—and was unionized only in 2015.

Hard-fought efforts like these developed the chops of many organizers like Guardado, who came to Arizona from California, Nevada and other more labor-friendly states.

“In California, everyone knows that your union has your back,” she said. “In Arizona, people had no idea what it was to have a union—and being a right-to-work state, they think, If you join the union, you’re going to lose your job. People don’t like unions here.”

So what do you tell them? I asked.

“It’s like: ‘Okay, what’s your plan for the next five years? How much longer can you work cleaning dirty rooms? How much money are you putting away for your kids’ education? Do you even know what do, to get your kids to college?’

“My own parents didn’t know what to do with me. They had no idea. They only thing they knew how to do was put food [on the table] and a roof over my head. I had to figure out the rest. It was through the union that I learned how to do this.

“People here have no idea. They have no hope. They’re like, ‘Well this is life, Betty. This is what it’s like for us here in Arizona. The companies don’t like us, Arpaio doesn’t like us. We’re disliked in the community and we’re disliked at work. The only thing we can do is just survive. We just put our heads down and we just keep working.’”

“So it was exciting—My God, there’s all these workers who just need grooming. You just give them a path and you tell them, ‘Follow me and you are going to get to a better place.’”

We were joined by Phoenix City Councilman Daniel Valenzuela, a union member and longtime activist first elected with union support in 2011, and reelected in 2015. He is a gentle, strong-looking young guy who looks like a movie firefighter, and is in fact a real-life firefighter. He’s a native of Phoenix with grown kids.

Overall turnout in Valenzuela’s district more than doubled in his 2011 election, he told me. “The Latino voter turnout increased by 488 percent,” he said, a result stunning enough to attract the notice of Time magazine and other media. “Those successes that were built, that were realized in November 2011, didn’t happen because the work started in January 2011. Those things don’t happen overnight.”

Valenzuela is passionate about redefining what it means to be a Phoenician to the rest of the country. “I have friends now who are on the LACity Council. I remember when NCLR [National Council of La Raza] and several others called for a boycott of doing business in Arizona. That hurt—I’ve explained that to NCLR. You had Latinos like me who grew up in these neighborhoods. Whose neighbors are being deported. Who’s raising his kids in these neighborhoods. Who love this city, and this state, so much. The last thing we needed was for people to boycott, or call the retreat.”

It’s brave to take on all the hostility here, I can’t help remarking.

“It was a matter of just proving that this is not who we are, [but] who we really are.”

Sena Mohammed is an Ethiopian-born refugee whose family has known terrible grief. A tiny young woman in a dark hijab and jeans, with a clear, brilliant gaze, she is a sophomore at ASU, where she majors in justice studies. Her father was long an activist on behalf of the Oromo people of Ethiopia, nearly 700 of whom are reported to have been recently massacred in Bishoftu. For all her slight stature, Mohammed is a commanding and persuasive speaker.

“At 4 years old I watched as my dad basically got snatched by the military,” she said. “It was like two in the morning and they came and took him, they shot our watchdogs and then shot bullets into the doors to get in.… [After a year] my dad and his friends escaped from prison, and they went into Kenya. He built a case, saying that he wanted to come to America. Only eight of the 13 kids could come. So my mom ended up choosing the youngest.… And that was really tough for her because she would be leaving some of her kids back there where it wasn’t safe.”

Five years later, the part of the family that had made it to Kenya was able to emigrate.

“I feel like I’ve come from a family of fighters. My dad was a fighter—he fought for what he believed was right. I feel like it’s my duty. For the things that I’ve gone through. When I came to America we had big aspirations, big dreams. We were like, Okay, we’re gonna be able to prosper, and just, do amazing things. And being where we feel safe… because we haven’t felt safe ever in our lives.”

Mohammed volunteers as a political organizer at CASE Action, a 501(c)(4) nonprofit organization affiliated with CASE, that is permitted to engage in partisan political activity. She and her growing group of student canvassers go out almost every day: They’re up to 40 contacts per day. “Our job is to sway them,” she told me. “Our job is to show them, ‘Look, I’m standing in front of you as a Muslim, and I want you to hear me.… And same thing with Latinos. Like, I’m not a rapist, I’m not a criminal.’”

When I arrived at the Phoenix home of Lucia Vergara, an airport worker who has served as president of Local 631, we found a hotbed of party activity, with hairdressers, cousins, and friends bustling around, doing makeup and nails, trying on clothes and having fun; her daughter’s quinceañera is only a few days away. She showed us her daughter’s scarlet ballgown and tiara and the custom-made dolls that would be given as gifts at the party.

Vergara herself had first been married at 16, she told us in her cozy kitchen over bottles of iced tea. She was born in Mexico and came to Arizona as a young child, and eventually her mother was able to obtain legal residency. Otherwise, she, like hundreds of thousands of Arizona residents, would have grown up facing the possibility of deportation at any moment, though she’d never lived in Mexico and had no connections there. “When I put myself in their shoes, I understand—it would be starting all over.”

Her whole life was just work, she told me. And then, through work, came her political education—joining the union, eventually becoming president and then a trustee. She too is a natural leader, a passionate speaker.

“If we let fear imprison us…,” she says, then stops. “Even if we go and speak with people, with a stranger, and maybe this person is white and might shut the door on us… no. We are human and we live in the same country, the same state, the same city. We have to have the courage, push ourselves. Believe in ourselves, and then inspire others…. What we’ve been able to do in 10 years here in Phoenix…bit by bit… nunca me imaginé llegar adonde estamos, la verdad. I never imagined we would get where we are now, truly.”

The recurring theme that emerges in talking with Phoenix’s new labor activists is that each of them has come to the realization that not only is his or her own contribution worth making but that it might be of real and lasting use to Arizona, as Maria Madrid explained at the end of our talk. There was a larger lesson in her words, for me: an exhortation to put aside the cynicism of many years of disappointment in progressive politics. Her face glowed as she described her enjoyment of going out canvassing or gathering support for her union, sometimes until eleven at night, because she’d learned how it would lead directly to a better life—and not only for herself. Yo lo que hago no lo hago para mí nadamás, es para todos, she said. “What I do I don’t do for myself alone, it’s for everyone.”