You know about Keystone XL—but activists want you to know about the record number of dirty, dangerous pipelines springing up elsewhere that grassroots action might have the power to stop.

Rick Perlstein

This past weekend I was thrilled to attend the second annual Great Lakes Bioneers conference in Chicago, which has been a wonderful introduction for me this year and last to the remarkably dedicated work citizens are doing around the concept of “resilience”—a word frequently used in psychology to refers to people’s ability to bounce back in the face of life challenges and which environmentalists have adopted into an umbrella term for practices centered around how communities can create a sustainable future within an unsustainable present—to build a new world in a shell of the old. In 2012, I learned about one of the movement’s coolest big ideas, “biomimicry”—the concept of better design through imitating nature. This year I learned about “food forests,” which is amazing stuff too—“a gardening technique or land management system that mimics a woodland ecosystem but substitutes in edible trees, shrubs, perennials and annuals.”

I also learned something horrifying. Please allow me to share.

You know something about tar sands, those petroleum deposits sedimented within mineral layers, concentrated in the Canadian province of Alberta. They can be converted into crude oil via a highly disruptive refining process, then transported to market via a process that is even more disruptive: overland and underwater pipelines. You know about tar sands, no doubt, because of the Keystone XL controversy. At Bioneers yesterday I attended a strategy session led by tar sands activists who were glad that the Keystone XL controversy has focused attention of the whole ghastly business; XL, because it crosses an international border, requires presidential action, which has provoked activists to launch a highly visible pressure campaign aimed at the White House. But they were worried about that attention, too—because “XL” serves a distraction from other, more proximate pipeline crises unfolding now, today, perhaps beneath a waterway or across a county near you, that you might be able to help stop now, through grassroots action.

It’s not just the record number of pipelines that are being built. There is also the newly flourishing and massively risky practice of reversing the directional flow of existing pipelines, often in conjunction with massive increases in pressure that the pipes were not designed to withstand (here’s a story about a pipeline reversal in which the volume will almost triple). That was almost certainly a major reason for the disastrous rupture of ExxonMobil’s Pegasus pipeline last March in Mayflower, Arkansas, which you may have heard about—or which you may not have heard about, given that the Federal Aeronautics Administration, in a suspicious move made in cooperation with ExxonMobil, immediately banned flights above the spill from descending below a floor of 1,000 feet, while inquiring reporters on the ground were told by local sheriff’s deputies, “You have ten seconds to leave or you will be arrested.”

One of the most monumental reversal-and-construction projects is taking place on a 485-mile pipeline that used to transport petroleum drilled in the Gulf of Mexico to the Midwest—but beginning in the spring of 2012 began moving tar sand-derived crude from Cushing, Oklahoma (the “Pipeline Crossroads of the World”), to the Gulf Coast for transportation onto the world market (a key concept—the world market; none of this has anything to do with American “energy independence”). It’s called the Keystone Pipeline Gulf Coast Project, and it has been the obsession of one of the remarkable panelists I heard last weekend. Earl Hatley, a Native American from Oklahoma and legendary environmental activist, was a principal in a lawsuit, dismissed by a federal judge last month, to keep that monstrosity from being completed. An exceptionally experienced observer of the wicked ways of the corporate carbon cowboys now deforming the North American landscape, he offered some shrewd assessments of the current state of play based on what he learned from that process.

The clever lawyers for the pipeline company TransCanada, you see, had devised a shifty way to get pipelines reversed, built or both, before opposition can have time to gel. They get a special kind of expedited permit from the Army Corps called “Nationwide Permit 12,” which is supposed to be limited to projects that disturb less than a half-acre of wetland in a “single and complete project.” But companies claim, in clear violation of the intent of the Clean Water Act and the National Environmental Policy Act, that each crossing of a body of water (there are more than a thousand for the project in question, adding up to 130 acres of high-quality forested wetlands) is a “separate” project, each falling below the threshold of scrutiny. That way they can avoid public hearings, avoid filing a environmental impact—can avoid any accountability at all, really. “It’s not a public process,” explains Hatley. (Nope. Only the lands are public.) Or, actually, processes—for what the NWP 12 scam allows is for pipeline companies to overwhelm the system, as the legal complaint from the Sierra Club and Clean Energy Future Oklaho ma explains, by “piecemealing” what is obviously a single project (even though you obviously can’t have a pipeline if it’s in pieces), “into several hundred 1/2-acre ‘projects’ so as to avoid the individual permit process.” So it is that Army Corps of Engineers, the named defendant in the suit, gets to mete out little chunks of permission every eleven miles or so, in secret, the public and the planet be damned.

The plaintiffs be damned, too. In a ruling early last month that is simply staggering in its bald deference to dollarocracy, an appeals panel ruled that because “the harm an injunction would cause TransCanada was significant,” and because $500 million had already been spent on the project, it was “undisputed that further delay [would] cost hundreds of thousands of dollars each day.”

That’s right: the plain intent of US environmental law could be contravened because it would cost a corporation. A court actually said this.

And get this. The court also said that the plaintiffs, the Sierra Club and Clean Energy Future Oklahoma, couldn’t have their injunction because—well, there’s only one way to put it: because they weren’t wealthy enough. As the AP article on the decision put it, it was impossible for the lawsuit to go further because “the Sierra Club and the other groups could not post a bond to cover TransCanada’s losses if the pipeline builder ultimately wins the lawsuit.”

For activists like Hatley, it was back to the drawing board. Sad news? Of course. You see why expedited permitting and construction are so important to oil companies: like Israel’s occupation on the West Bank, once they establish their “facts on the ground,” the process feels impossible to reverse. This process, by the way, was personally endorsed by President Obama, who traveled to Cushing last year to sing hosannahs to building more pipeline. (After all, the National Security State needs tar sand crude to maintain a viable imperial presence around the globe. That’s why they call oil a “strategic commodity.”)

But look here: there is (as a certain presidential candidate used to like to say) hope. You can’t have a pipeline, after all, if it’s in pieces. What if We the People found a way to break the chain? To, as it were, perforate the pipe?

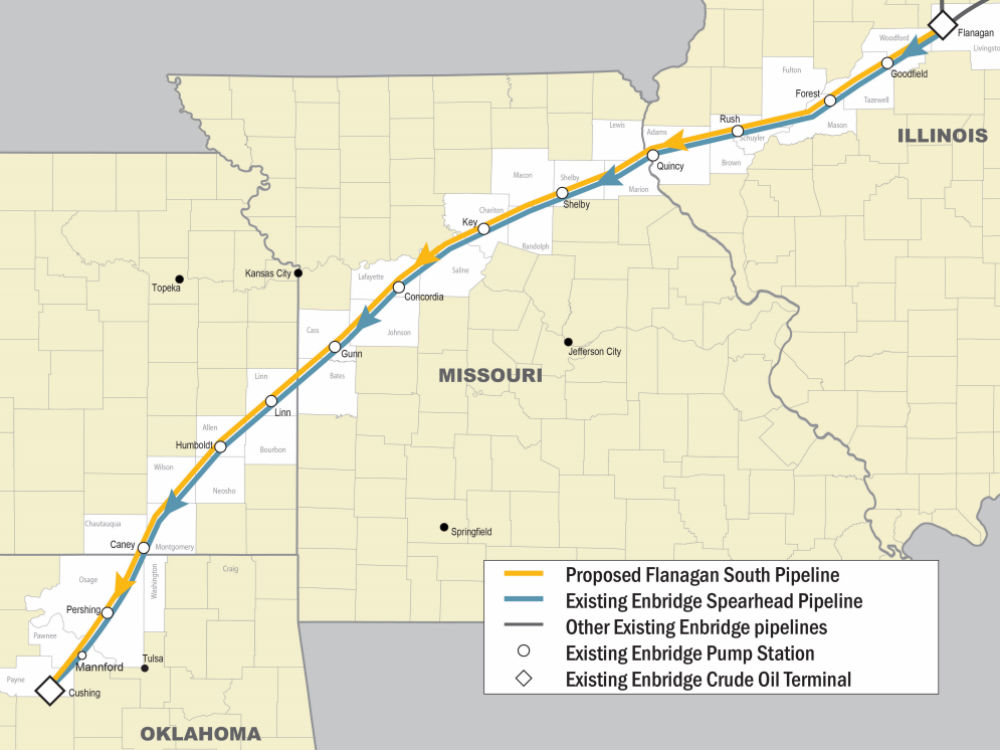

That was the most exciting part of the Bioneers session for me. Look at the map above. That’s the Flanagan South pipeline project being planned by TransCanada’s rival Enbridge (slogan: “Where energy meets people”), set to run 600 miles from Flanagan, Illinois, to Cushing, Oklahoma, sending some 600,000 barrels a day across states of Illinois, Missouri, Kansas and Oklahoma. Which makes for lots of disrupt-able links in the chain. And here’s where the disruption could come from. A model one of the activists in the audience at the session pointed to, the Tar Sands Free Town campaign, “[builds] on model resolutions already adopted in Bellingham, Washington, [in which] individual municipalities can pass resolutions that keep fuel from tar sands refineries out of their towns.”

Those burgs that dot the map from Flanagan to Cushing: Caney and Humbolt and Lynn in Kansas; Gum and Concordia and Key and Shelby in Missouri; Goodfield and Florence and Rush and Quincy in Illinois—those are the towns Enbridge will be eyeing for colonization-via-fossil fuel pump stations and refiners. What will happen when the colonizers arrive? Hatley described his own observations from Oklahoma: arrogant out-of-town oil men will refuse to patronize local businesses, break promises to provide local jobs, condescend standoffishly to local citizens. “You go through the cafes…. You stand up, and you start having rallies. You let people know.” And, he said, people respond.

Another panelist, MacDonald Stainsby, who is based in Vancouver, told an extraordinary story about the time he visited a village in Africa. The people there were amazed when he recited to them, as if he were a clairvoyant, exactly the history of double-dealing and mendacity and environmental abuse they’d suffered when an oil multinational came to town. How did he know? they asked. Because, he replied, that was exactly what they did to towns in Canada—and everywhere else. Which is why, Hatley explained, activists should try to “catch the process before it goes forward,” from the bottom up. That is where the hope lies.

Organize with these facts from the pipeline-rupture epidemic, which have flown largely below the media radar. A Koch-owned pipeline spilled 400 barrels in Texas last week. “Details are scarce regarding the cause of the spill,” Alternet reports, but that’s nothing compared to what happened a few weeks earlier: “a pipeline that spewed over 20,000 barrels of crude oil into a North Dakota wheat field went unreported for eleven days until it was discovered by a farmer harvesting his wheat. A subsequent Associated Press investigation found nearly three hundred oil 300 oil spills and 750 oil field incidents have gone unreported in the state since January 2012 alone.” According to a report from the watchdogs at Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility, the office at the Department of Transportation in charge of regulating 2.6 million miles of pipeline spends three times more hours hobnobbing at industry conferences than it does responding to spills, explosions and other incidents on the ground.

And how do the companies respond when evidence of a crisis emerges? Hatley said that when the monitors at Enbridge’s far-off headquarters spied low pressure in their pipe flowing below Mayflower, Arkansas, they didn’t shut down and look into the possibility of a rupture. They amped up the pressure instead—three separate times. Meanwhile a pipeline safety expert with forty years’ experience predicts that the chance of rupture of a pipeline repurposed for tar sands that runs through the most populated part of Canada and crosses waterways providing drinking water for millions of Canadians is… “over 90 percent.”

And last summer, the National Wildlife Federation sent divers down to inspect the sixty-year-old pipelines Enbridge operates beneath the Straits of Mackinac—a major tourist area in Michigan—after the company (and the federal government’s Pipeline Hazards Safety Administration) refused for two years to release information about their safety and integrity or even their location. You can watch the video here to see what they found: “pipelines suspended over the lakebed, some original supports broken away (indicating the presence of corrosion), and some sections of the suspended pipelines covered in large piles of unknown debris.” Among the cities with refiners that receive tar sands from this eminently admirable company, according to Clean Energy Future Oklahoma, are Joliet, Illinois; Whiting, Indiana; St. Paul, Minnesota; Toledo, Ohio (they have two); and Tulsa, Oklahoma.

Enbridge began construction this summer on Flanagan South, using the obnoxious Nationwide Permit 12 process. The fact that you’ve heard of Keystone XL but not this, even though the route might nearly snuggle up to your front porch—it comes within twenty miles of Peoria, Illinois, to take one example—has nothing to do with size: according to Midwestern Energy News, the project will carry “600,000 barrels a day initially for the Flanagan South, and 783,000 barrels per day once combined with the Spearhead, an existing pipeline that largely runs parallel to the proposed Flanagan route,” compared to 830,000 barrels for Keystone XL.

Midwesterners, let’s get to work. It won’t be easy: reports the NWF of its underwater adventure, “despite having cleared our dive work with the U.S. Coast Guard, several Congressional members, and Homeland Security, our staff and the dive crew had uncomfortable interactions with Enbridge representatives. As soon as our team set out on the water, we were quickly accompanied by an Enbridge crew that monitored our every move. This monitoring did not stop at the surface: Enbridge also placed a Remote Operated Vehicle (ROV) into the water to watch our team.”

I’m sure Enbridge had only the most public spirited of intentions. Reports the company website, “Government regulations for the approval and maintenance of pipelines are transparent and rigorous. With our focus on safety, and our commitment to adopting state-of-the-art technology, Enbridge meets and often exceeds those regulations—and that has earned us recognition as an industry leader. But we know that’s not good enough. Nothing is more important to us than the safety of our pipelines, our communities, and the environment. We continue to strive in the areas of monitoring, prevention, response, and new technology for a delivery record of 100%.”

What liars. Sounds like a villain worthy of your most mighty attention.

Zoe Carpenter highlights another under-reported environmental crisis: coal mining in the Powder River Basin.

Rick PerlsteinTwitterRick Perlstein is the author of, most recently, Reaganland: America's Right Turn 1976–1980, as well as Before the Storm: Barry Goldwater and the Unmaking of the American Consensus and Nixonland: The Rise of a President and the Fracturing of America.