The Pentagon’s Flailing Campaign Against Hate

How the military continues to downplay the spread of extremism in its ranks.

As the rolling institutional crisis of American political life unspools, a key accelerating force has gone largely unchallenged: radical right-wing military extremism.

It’s a touchy subject for many reasons. To begin with, the military has long been linked to the country’s inclusive civic ideals. As an achievement-driven meritocracy, the service is seen as a genuine outpost of equal opportunity, drawing recruits from all class and racial backgrounds and inculcating in them an ethos of camaraderie, accountability, and shared sacrifice. What emerges, we’re told, is America’s best—the enemy of our enemies, a fighting force that can do no wrong.

These military myths derive their strength from moments of real interracial solidarity and support, but also from blind patriotism, powerful propaganda, and historical ignorance. Grinding against the military’s self-spun narrative of inclusion are clear facts and simple logic, showing how a foundationally white institution engaged in the volatile work of violence will inevitably end up fueling extremist behavior, especially in a country, such as ours, with a gruesome legacy of racism.

The military has long understood this truth but has rarely been willing to admit it. The Army came close in a 1998 report that warned that “military virtues such as fitness, proficiency with weapons and tactics, physical courage, and camaraderie fit comfortably with a white supremacist ethos.” But that assessment omitted a decisive factor behind the spread of extremism in the US military: the cultivation of a finely honed instinct among soldiers—to join a unit, identify an enemy, and fight to save America. In a country like the present-day United States, riven by conflicts that increasingly threaten our ever-fragile standing as a multiracial democracy, the forces of MAGA reaction are exploiting that instinct on behalf of a radical new mission.

At least 188 people with military backgrounds participated in the January 6 insurrection, and many more rooted from the sidelines. A few weeks later, a dozen members of the National Guard force that was assembled to fortify the Capitol ahead of Joe Biden’s inauguration were dismissed on the grounds of possible ties to extremist groups. Veterans were disproportionately represented in the leadership ranks of the paramilitary groups that launched the assault on January 6, like the Proud Boys and the Oath Keepers; indeed, the latter portrayed itself as a veterans’ support group.

As it happened, January 6 also marked the one-month anniversary of the nomination of the nation’s first Black secretary of defense, Lloyd Austin. Amid the chaotic authoritarian mania of the Trump administration—which hit the military especially hard—Austin’s appointment appeared to be a welcome and long-overdue stabilizing force. In breaking the “brass ceiling” in the executive management of the armed forces, Austin was heralded, like former Joint Chiefs chair Colin Powell before him, as the public face of a post-racial military, in which stubborn divisions along racial and ethnic lines could, at long last, be put to rest.

The shock of the insurrection made it clear that the military’s racist elements were alive and well. Austin quickly responded by ordering US military units worldwide to “stand down” for a day to discuss extremism. He also promised a series of far-reaching reforms. Austin seemed well positioned to meet this moment: Throughout his career, starting as a West Point cadet, he’d been determined to demonstrate his merit, rise through the ranks, and achieve perfection. But he was also more aware than most of the pitfalls faced by a military man of color and, perhaps, was clear-eyed about the strict expectation that soldiers subordinate their own identities on behalf of the institution.

Much had changed at West Point by the time Austin arrived there in 1971 as one of around two dozen Black cadets in a class of roughly 1,000, though not nearly enough. Numerous monuments on campus were dedicated to the Confederate general and former West Point superintendent Robert E. Lee, including a large portrait of the slave owner that hung in the library. Not far from there, at the entrance of a science building, was a large bronze plaque that featured a hooded member of the Ku Klux Klan.

Despite his die-hard allegiance to the color-blind ideals of the military meritocracy, Austin could not avoid ugly reminders of racial prejudice in the armed services. In 1993, he became a commander in the 82nd Airborne Division at the country’s largest military base, Fort Bragg, which was named after a slave-owning Confederate general. His time there overlapped with James Burmeister II and Malcolm Wright, two skinhead paratroopers who, in 1995, murdered a Black couple in nearby Fayetteville, N.C.—an event that shook Austin, and the Army, to their core.

Austin’s background lent a historical loftiness to his post–January 6 directives, but it also presented a slew of intensified challenges and threats. Like Barack Obama before him, he adopted a calm, measured approach to addressing white hate. But since the rise of Trumpism, this was no longer a viable posture. Austin was confronted with a new political scene, one dominated by a highly organized and racially unhinged right on the one hand and a delusional, spineless liberal establishment reaching for Obama-style consensus on the other.

Republicans moved against Austin within days of his proposed reforms. GOP leaders had initially been unnerved by the failed MAGA coup, but once the dust had settled, they proceeded to harness military rage for political ends.

Within a matter of months, and facing little pushback from Democrats, Republicans had derailed Austin’s efforts, tapping into legitimate public frustration with the military-industrial complex to undermine a rare push for racial progress. In upending the military’s halting reckoning with the extremist elements in its ranks, GOP leaders ratified a status quo that, in the words of one former defense official, “leaves the door open to some type of future catastrophe.” What form that would take is unclear, though many conservative figures have floated possible scenarios—including the disgraced retired general Michael Flynn, who has endorsed a Myanmar-style military coup on American soil.

Flynn may be a kook, but he is hardly the only American officer to embrace military authoritarianism. A whopping 124 retired generals and admirals signed a letter contesting the 2020 election results. That pronouncement prompted three liberal-leaning retired generals to write a Washington Post op-ed warning of a coming military coup.

The military ultimately suppressed the January 6 insurrection, but only after a series of puzzling delays. Ryan McCarthy, the secretary of the Army at the time, became virtually invisible in the days leading up to the attack. He kept the same posture during the siege; at one point, a panicked subordinate was forced to run around the Pentagon looking for him.

William J. Walker, the now-retired major general who led the D.C. National Guard that day, was blunt to Congress in his assessment of the Pentagon’s sclerotic response. “Somebody or somebodies were willfully, deliberately delaying making the decision” to help put down the attempted coup, said Walker, who is Black. “I think it would have been a vastly different response if those were African Americans trying to breach the Capitol.”

In preparing for the discussions to be held during Austin’s stand-down, commanders were directed to zero in on the military’s enlistment oath, a noble credo professing allegiance to the Constitution and the orders of the president and high officers that all service members are expected to faithfully observe. “There are active verbs in that oath that matter,” John Kirby, then the Pentagon’s press secretary, said. The exercise “was a chance to revisit what we’ve all promised to do, and what we’ve all promised to serve.”

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →It was a well-meaning message, but a deeply flawed one. By linking the stand-down to the oath, the military relegated its attempt at reform to a set of platitudes. No data was collected, no tips received.

At the same, the Pentagon’s instant pivot to the oath demonstrated its ongoing blindness to how its sweeping, nationalistic rhetoric is easily exploited by radical movements. As experts on extremism noted, the stand-down employed a set of talking points that were eerily similar to the ones promulgated by far-right groups such as the Oath Keepers, who have warped and weaponized Pentagon language in their drive to recruit thousands of members with military and law enforcement backgrounds.

The urgency and gravity of the stand-down exercises also varied widely across the branches of the armed forces and their individual units, thanks to the broad discretion given to commanders. Some units held candid conversations on racism in the ranks; others settled for bureaucratic, box-checking confabs. One Marine officer said, “It felt like they were telling us just how far people could go to avoid trouble.”

Kristofer Goldsmith, an Iraq War veteran who now dedicates himself to doxxing neo-Nazis, told me that stand-downs generally offer little more than an “opportunity for commanders to pat themselves on the back.” He noted that commanders have no real knowledge or training in extremism and thus can’t play a substantive role in advancing such important conversations. This top-down model was sure to backfire, he said, in part because some commanders with extremist leanings seized on it as an opportunity “to indoctrinate their troops.”

In April 2021, Austin launched the Countering Extremism Working Group, selecting Bishop Garrison, a fellow Black West Point graduate with two Bronze Stars who served combat tours in Iraq, to lead the project. Garrison was tasked with, among other things, devising better ways to screen out problem recruits and updating the Uniform Code of Military Justice to empower judge advocate generals to charge hate crimes. The group would also seek to increase cooperation between military and civilian law enforcement authorities and would commission an independent study on the extent of extremism in the military.

Garrison was given just 90 days to enact these ambitious plans. He quickly built a team of 100 people representing all six branches of service; he also drew from many relevant offices, such as personnel and readiness, intelligence, and the office of the general counsel. But the group immediately faced intense resistance, from both inside and outside the Pentagon.

The first whiff of public opposition appeared just a few days after the group was formed. That’s when two four-star commanders each claimed (under oath before the Senate Armed Services Committee) that there were “zero” extremists among the 170,000 service members under their collective purview—claims that Garrison took issue with. “There is a problem with extremist behavior in the military,” he announced. “That is to say that one extremist is one too many.”

Shortly thereafter, Garrison himself became the target of a coordinated smear campaign that typified the very racism he was trying to confront. The first salvo was an inflammatory article referring to him as “The Pentagon’s Hatchet Man in Charge of Purging MAGA Patriots and Installing Race Theory in the Military.” It was published by Revolver News, a far-right website founded by Darren Beattie, a Trump speechwriter who’d been fired after the press reported that he’d spoken at a white nationalist conference in 2016.

Beattie’s attack quickly moved up the conservative media food chain, picked up by Fox News before landing in Congress. In late May, 30 Republican lawmakers signed a letter singling out Garrison and complaining of “creeping left-wing extremism” in the military. Around this time, Garrison started receiving death threats.

Some of the most powerful criticism came from Republican military veterans in Congress who for years have used the sheen of respectability conferred by their service to launder extremist ideas into the mainstream. Leading this fight were Senator Tom Cotton of Arkansas, a former Army officer, and Representative Dan Crenshaw of Texas, a former Navy SEAL, who invited “whistleblowers” to contact their offices with stories of anti-racist wokeism run amok. Representative Michael Waltz of Florida, the first Green Beret in Congress, vehemently criticized a West Point course focused on critical race theory.

While most Republicans masked their attacks as part of a “war on wokeness,” Waltz went a step farther, introducing legislation to explicitly prohibit federal funds from being used to investigate military extremists. Senator Tommy Tuberville of Alabama was similarly transparent when asked by a Birmingham public radio station if he thought white nationalists should be allowed to serve in the military. “Well, they call them that,” he said. “I call them Americans.” Tuberville had, by then, spent weeks blocking all pending senior promotions due for Senate approval—an unprecedented move that he claimed was necessary to combat access to abortion within the military.

All of these reactionary pronouncements and maneuvers spoke loudly to the military’s extremism problem—yet Democrats essentially failed to call it out. A rare exception came when Senate majority leader Chuck Schumer deemed Tuberville’s comments “utterly revolting.” Even so, Schumer failed to condemn Tuberville further by, say, urging his removal from the Senate Armed Services Committee.

Even Austin seemed unwilling to examine the issue fully. The defense secretary continued to insist, in the midst of withering political attacks, that extremist ideology is a corrosive force within the military—but he also claimed, without citing any evidence, that it was not as big an issue as some believed it to be. In one press conference, he assured the public that “99.9 percent of our service men and women [are] doing the right things each and every day.”

We may never know whether Austin’s claim is true; the working group’s study on the scope of military extremism has become stuck in perpetual limbo. Yet the available research on the question continues to raise red flags. The portion of domestic terrorist actions involving members of the military has skyrocketed in recent years, to around 6.4 percent. This means that military affiliation is today the single strongest predictor of extremist mass violence in America.

As the political attacks on the working group stretched into the summer, CNN reported that Austin’s public support for Garrison “appeared to evaporate.” One anonymous official told the network that he was “deemed to be a distraction.” The Pentagon hadn’t exactly relinquished interest in the question of extremist elements in the military—but the Beltway-savvy senior brass seemed willing to scuttle the effort in order to appease far-right congressional critics with outsize power over the military’s purse strings. And sure enough, the appropriators drafting the final 2022 defense bill boosted spending while stripping out eight provisions meant to combat domestic extremism.

At the end of the year, Garrison’s working group produced a report that sketched out some modest progress. After intense debate, the military managed to update its definition of extremism, largely by expanding the scope of prohibited behavior to online activities. The group also produced materials warning service members transitioning to civilian life of the dangers posed by extremist groups, and it updated the armed services’ screening process to identity potentially dangerous recruits.

The report detailed these changes and laid out 20 or so solid recommendations for the future. A couple of those have been partially implemented, though the vast majority appear to be dead in the water, including the most ambitious idea: to create a Behavioral Threat Analysis Center within the Pentagon that researches new extremist trends, responds to tips, and investigates traitors.

Though the military has updated the screening questionnaire used by recruiters, it hasn’t been widely enforced. In August, the Pentagon’s inspector general found that only 40 percent of would-be recruits in a sample were asked about or responded to questions about extremist or gang ties. Only 9 percent were screened for tattoos that could indicate such affiliations.

Overlapping efforts to better understand how veterans are radicalized have also fallen flat, mostly because of reticence by the Department of Veterans Affairs, which, according to a congressional source, “isn’t open to engaging on this.”

In 2022, leaders of the House Veterans’ Affairs Committee, then still under Democratic control, did manage to produce an illuminating report finding that extremists with a military background have killed 314 people and injured another 1,978 over the past three decades. This work occurred without any Republican input—a striking development, since the committee has traditionally been composed of moderate members of both parties.

Carrie Lee, an associate professor at the US Army War College, said that the failure of these initiatives is both shocking and unsurprising: “There’s a tendency inside the military to say, ‘OK, we checked the box, we did the extremism stand-down, congratulations, we have no more extremism, let’s move on.’”

Afew months after he launched these ill-fated efforts at reform, Austin returned to West Point, where he addressed the graduating class of 2021. Despite the military’s decidedly equivocal record on racial progress and West Point’s persistently discriminatory subculture, the ceremony offered a bit of hope in the form of 148 Black graduates—a major increase from Austin’s era.

Still, in his speech, Austin acknowledged the startling similarities between today’s force and the Army he had entered. Now, as then, military officers served a nation in crisis: “a democracy under strain, economic fallout, painful issues of racism and discrimination, social tensions and the end of a long and controversial war.”

The truth is that every major US military conflict has led to a domestic surge in racist political violence. Still, Austin was right to spotlight the Cold War as a particularly disturbing era—both for its resurgent right-wing extremism and for the military’s all-too-familiar unwillingness to grapple with the problem.

Back then, stark evidence of Ku Klux Klan activity was popping up at military bases from Vietnam to Camp Pendleton, Calif. A major hot spot was Austin’s old base in North Carolina, Fort Bragg. In 1986, The New York Times uncovered evidence that US Marines and soldiers based at Fort Bragg and Camp Lejeune, 130 miles to the east, were involved in white power groups. That same year, a retired member of the Special Forces wrote to a North Carolina legislator warning that if leaders failed to support the needs of white citizens, “then we have no alternative but to resort to armed revolution to replace them.”

Then–Defense Secretary Caspar Weinberger denied that there were widespread racist and extremist sentiments in the military, but he also issued a directive instructing service members to “reject participation in white supremacy, neo-Nazi and other such groups which espouse or attempt to create overt discrimination.”

The inadequacy of the Pentagon’s response was made brutally clear with the racist murders at Fort Bragg in 1995. Austin, who was a junior officer at the time, has declined to specify what role, if any, he had in the Army’s reaction to the killings. In their wake, the brass investigated the base and identified nearly 20 white supremacist skinheads—plus a smaller opposing force of anti-racist skinheads. The Army defensively noted that this population represented less than 1 percent of the Airborne force; some leaders claimed that the skinheads had been impossible to spot.

Austin echoed this narrative during his Senate confirmation hearings in 2021, explaining that “we just didn’t know what to look for” in the effort to root out extremism at Fort Bragg. Yet the base had already been identified as a breeding ground of white hate. Indeed, the months leading up to the murders were marked by a slew of violent assaults in neighboring communities committed by skinheads with suspected military ties.

One of the Fort Bragg murderers had previously made racially pointed remarks toward a Black soldier and had fought him. His room had Nazi flags on the wall, and his personnel file showed he’d been counseled for wearing a Nazi medallion.

Paul Eaton, a retired Army major general, told me that he found it hard to believe that extremism in the military could go undetected so easily. “Squad leaders are expected to know their men absolutely, as well as their families and their extended families,” he said. “You hear the term ‘brotherhood’—that’s what it is. For a guy to survive as an extremist would take almost a conspiracy to allow it to occur and endure.”

Indeed, in the wake of the Fort Bragg murders, some commanders quietly admitted that they’d been aware that the toxic ideology was present at the base. Some tolerated it because they thought military values would ultimately counteract it.

In 1998, a Pentagon report found that far-right groups were targeting young recruits to gain access to weapons and military training. Eleven years later, the Department of Homeland Security documented growing links between veterans and domestic terrorism in a report that was viciously opposed by Republicans and conservative veterans’ groups like the American Legion. Ultimately, the team responsible for this report was disbanded, and its findings were largely ignored.

Austin’s failed effort to launch a real reckoning with the military’s growing alliance with the forces of the far right was a predictable epilogue to this unfortunate history. Nearly three years after January 6, the military’s most visible changes are cosmetic. West Point has removed its plaque honoring the Klan and has scrubbed its Confederate monuments. A bunch of military bases and one VA hospital named after Confederate leaders were also renamed, including Fort Bragg; in June, it was rechristened Fort Liberty.

Even these minimal changes have drawn outraged opposition on the right. The most vile gesture came from Virginia Governor Glenn Youngkin, who responded to allegations of racism at the Virginia Military Institute—which was founded in 1839 to fend off slave rebellions—by appointing four white conservatives to the school’s board. (One had apparently resigned from the board earlier in objection to the proposed removal of an on-campus statue of the Confederate general Stonewall Jackson.)

The changing of base names and the quiet retirement of racist mottoes and monuments may bring some level of spiritual peace to service members of color. But by themselves, they’re a woefully inadequate response to the scourge of extremism incubating in military units. In a local news report on Fort Bragg’s renaming, Grilley Mitchell, president of the Cumberland County Veterans Council and a Black man who grew up in the Jim Crow South, offered this incisive appraisal: “Changing the name, it’s not going to heal anything, it’s not going to fix anything. To me, it covers it up by putting a coat of paint on something.”

Indeed, military units in and around Fort Liberty continue to be plagued by white supremacist activity. Last year, prosecutors uncovered the Nazi leanings of a member of the 82nd Airborne after he was discharged on another matter—including social media posts in which he said he’d joined the Army so that he could become more proficient in killing Black people.

More recently, prosecutors discovered that a 23-year-old Airborne soldier named Noah Anthony had planned an “operation to physically remove” Black and brown people from the four counties surrounding the base. Anthony’s case is also noteworthy for the way his plot was uncovered. He was not rooted out by an in-depth military investigation or a background check or because a fellow soldier had tipped off the brass. No, his hateful beliefs and agenda came to light via a random search of his car. As military police rummaged around, they found a handgun, ammunition, and an American flag bearing a swastika where the 50 white stars normally appear.

A few weeks after Anthony had pled guilty to gun charges, Fort Bragg was renamed, an occasion that spurred a patriotic statement from its garrison commander. “Liberty lives here,” he said. “It is part of our ethos, and it’s part of who we are.”

Disobey authoritarians, support The Nation

Over the past year you’ve read Nation writers like Elie Mystal, Kaveh Akbar, John Nichols, Joan Walsh, Bryce Covert, Dave Zirin, Jeet Heer, Michael T. Klare, Katha Pollitt, Amy Littlefield, Gregg Gonsalves, and Sasha Abramsky take on the Trump family’s corruption, set the record straight about Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s catastrophic Make America Healthy Again movement, survey the fallout and human cost of the DOGE wrecking ball, anticipate the Supreme Court’s dangerous antidemocratic rulings, and amplify successful tactics of resistance on the streets and in Congress.

We publish these stories because when members of our communities are being abducted, household debt is climbing, and AI data centers are causing water and electricity shortages, we have a duty as journalists to do all we can to inform the public.

In 2026, our aim is to do more than ever before—but we need your support to make that happen.

Through December 31, a generous donor will match all donations up to $75,000. That means that your contribution will be doubled, dollar for dollar. If we hit the full match, we’ll be starting 2026 with $150,000 to invest in the stories that impact real people’s lives—the kinds of stories that billionaire-owned, corporate-backed outlets aren’t covering.

With your support, our team will publish major stories that the president and his allies won’t want you to read. We’ll cover the emerging military-tech industrial complex and matters of war, peace, and surveillance, as well as the affordability crisis, hunger, housing, healthcare, the environment, attacks on reproductive rights, and much more. At the same time, we’ll imagine alternatives to Trumpian rule and uplift efforts to create a better world, here and now.

While your gift has twice the impact, I’m asking you to support The Nation with a donation today. You’ll empower the journalists, editors, and fact-checkers best equipped to hold this authoritarian administration to account.

I hope you won’t miss this moment—donate to The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editor and publisher, The Nation

More from The Nation

The Longest Journey Is Over The Longest Journey Is Over

With the death of Norman Podhoretz at 95, the transition from New York’s intellectual golden age to the age of grievance and provocation is complete.

The Shocking Confessions of Susie Wiles The Shocking Confessions of Susie Wiles

Trump’s chief of staff admits he’s lying about Venezuela—and a lot of other things.

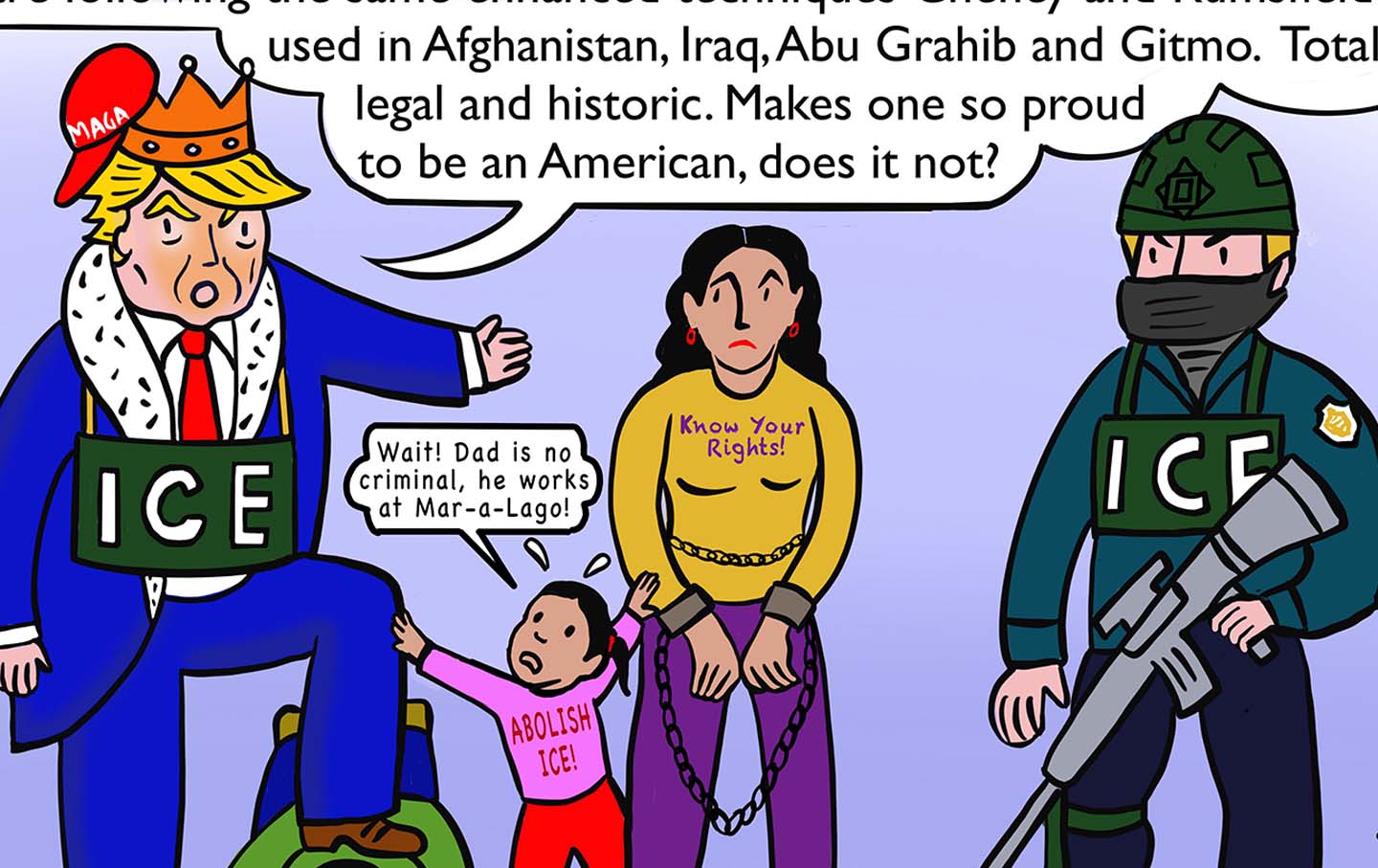

The King of Deportations The King of Deportations

ICE’s illegal tactics and extreme force put immigrants in danger.

The Epstein Survivors Are Demanding Accountability Now The Epstein Survivors Are Demanding Accountability Now

The passage of the Epstein Files Transparency Act is a big step—but its champions are keeping the pressure on.

Mayor of LA to America: “Beware!” Mayor of LA to America: “Beware!”

Trump has made Los Angeles a testing ground for military intervention on our streets. Mayor Karen Bass says her city has become an example for how to fight back.

Breaking the LAPD’s Choke Hold Breaking the LAPD’s Choke Hold

How the late-20th-century battles over race and policing in Los Angeles foreshadowed the Trump era.