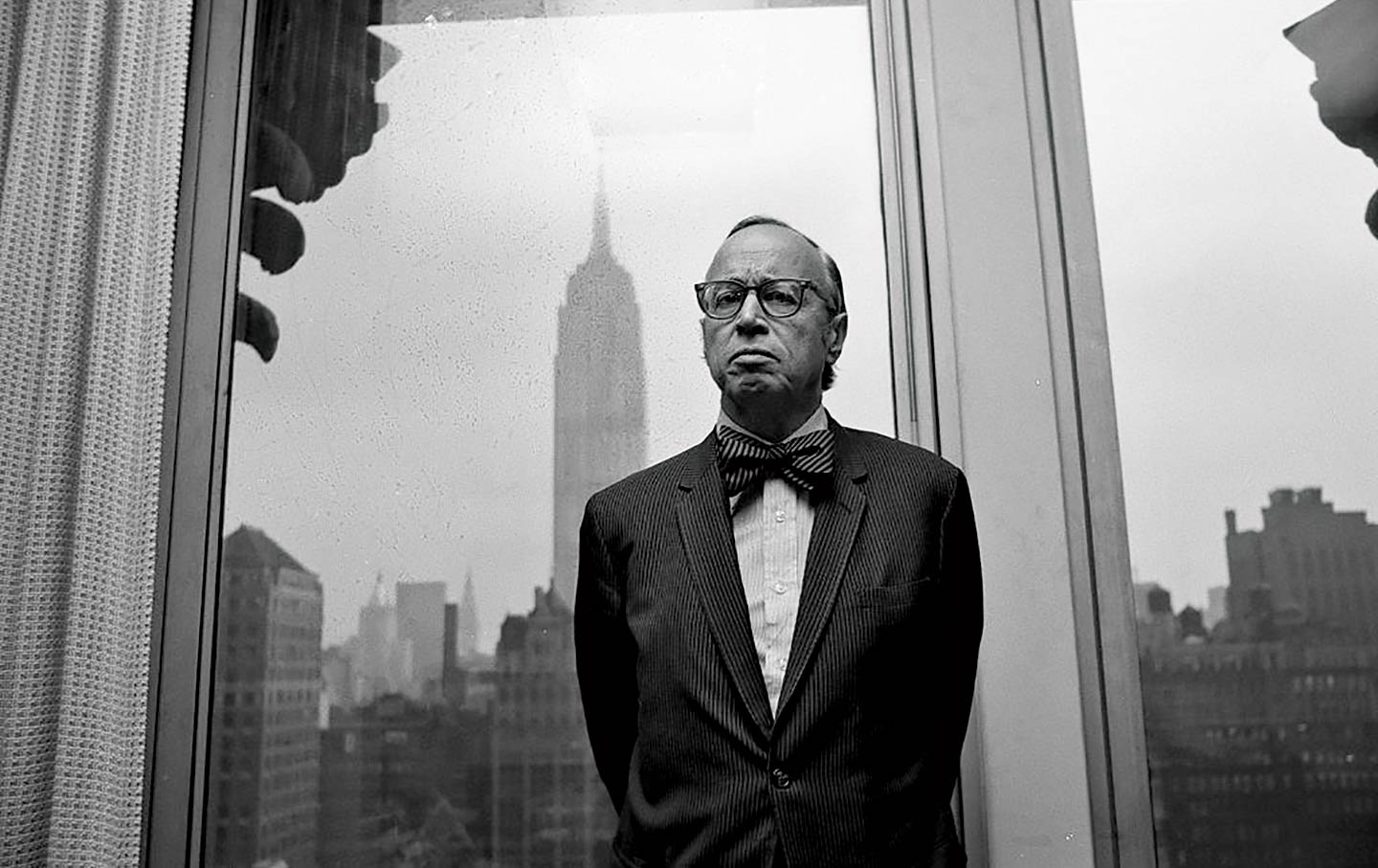

Arthur Schlesinger, 1974.(Waring Abbott / Getty Image)

In the years shortly after the Second World War, a new idea caught fire in the North Atlantic: consensus. The postwar settlement had divided the world into two spheres. In the West, liberal democracy—sometimes more social democratic, sometimes more laissez-faire—dominated; in the East, various forms of socialism and communism. Many intellectuals on the right and left decried this new age of conformity. Liberals, on the other hand, celebrated it. It marked their arrival: They had won the war of ideas, if not control.

Consensus soon caught on within the historical discipline. In the first half of the 20th century, a group of Progressive Era historians—Frederick Jackson Turner, Charles Beard, V.L. Parrington—had argued that the history of American politics hinged on a series of social and political conflicts. In the prosperity and calm of the postwar years, historians embraced the opposite view: The American past was defined not by a contest over ideas and power but by ideological agreement—a long-standing fidelity to the liberal tradition.

Some within this consensus school made their case more critically than others (Richard Hofstadter acerbically observed that liberalism’s dominance had created “a democracy in cupidity rather than a democracy in fraternity”). But a more popular school found in it the resources for a newly assertive Cold War liberalism: America’s ability to find common ground was its “genius.”

One of the few dissenting voices against the idea of consensus in these years was a young Harvard professor by the name of Arthur Meier Schlesinger Jr. Schlesinger was an outspoken liberal, and so he was not, like Hofstadter, critical of liberalism’s ascendance. But as the son of a Progressive historian, he also argued that it had arrived there through conflict, not consensus. In his first major works of history—The Age of Jackson and his three-volume epic, The Age of Roosevelt—he set out to prove his thesis, documenting how a bellicose view of politics had created and sustained the Democratic Party, first with its rise under Andrew Jackson and then with its revival under Franklin Roosevelt and the New Deal. Schlesinger went even further in his 1949 Cold War treatise, The Vital Center: If liberals and social democrats were to beat back communists abroad and right-wing conservatives at home, they needed a more realistic view of politics. History and human reason alone would not do the work for those on the side of progress. Social change required the tactics of war: intrigue, argument, duplicity, and confrontation. This is what he meant by a vital center—not a politics of accommodation, but one of all-out attack.

Over the years, Schlesinger’s vital center hasn’t often been remembered this way. Because of his strident anticommunism and his close ties to postwar Democrats—in 1961, he was appointed special assistant to John F. Kennedy—many of his critics saw Schlesinger as the avatar of consensus. Later, when a young cohort of “New Democrats” and neoliberals (yes, they used the term) began to push the Democratic Party to the right, The Vital Center was invoked to justify their triangulations and compromises. (Shortly after signing welfare reform into law in 1996, Bill Clinton declared before an audience of DLC members: “we have clearly created a new center…the vital center.”)

As we learn from Richard Aldous’s compellingly narrated and well-researched biography of Schlesinger, this was perhaps not so much an accident as an inadvertent result of his own ideas. Schlesinger always believed that his vital centrism was at the behest of a more egalitarian society—the welfare state in the United States and social democracy in Western Europe. But his instrumental view of politics was also always at risk of hardening into an ideology of its own. Like all forms of political and moral realism, the means could quickly become ends and power the sole prize.

Schlesinger appeared to recognize the dangers of this slippage and was often on guard against it. (Writing in a riposte to Clinton’s DLC speech, he insisted that “If anyone really thinks that turning national and international problems over to state governments and the private market will end our troubles, they are due for further disillusionment.”) But like his Jacksonian and New Deal heroes, Schlesinger also believed that power was the ultimate measure of politics, even if it was secured at the cost of one’s own commitments. When Schlesinger and his wife were asked, shortly after his public scolding of Clinton, if they would join Bill and Hillary for dinner in Martha’s Vineyard, the pair flew out the next week: Schlesinger knew the hand that fed him and other liberals. He was also flattered to once again be at the center of American politics, reporting in his journal that the whole affair was “an immensely pleasant, even cozy evening.” His only real complaint: “the drinks were served…very slowly.”

Schlesinger’s preference for the power politics and company of presidents was not a part of his upbringing, which was largely defined by the Midwestern egalitarianism of his father, Arthur Meier Schlesinger Sr., and his father’s generation of Progressive historians. Born in Columbus, Ohio, in 1917, Schlesinger descended from German-speaking Jewish and Catholic immigrants on his father’s side and downwardly mobile WASPs on his mother’s. American history and progressive politics ran on both sides. Schlesinger Sr. had studied under Charles Beard and James Harvey Robinson at Columbia and taught their breed of social history at Ohio State; he had also inherited their left-wing politics, throwing himself into a variety of radical causes, including a failed attempt to launch a third party. Schlesinger’s mother was also politically engaged: An outspoken suffragette, she was—at least according to family lore—a relative of the Jacksonian historian and statesman George Bancroft.

Like many academic families, the Schlesingers moved around a lot during Arthur’s childhood. From Columbus, they went to Iowa City, where Schlesinger Sr. held a teaching post until 1924, when Harvard and Frederick Jackson Turner came calling. In Cambridge, the family finally began to establish deeper roots. They built a large Colonial Revival in upscale Gray Gardens, and the Schlesinger men embraced the town’s patrician tastes—bow ties, expensive eyewear, and summers at the Cape.

When Schlesinger arrived at Harvard, at the age of 15, he immediately became known as “little Arthur.” Like his father, he was drawn to history, studying with Perry Miller and writing his undergraduate thesis on the antebellum radical Orestes Brownson. His father had chosen the subject, and he would later also help to get the book published. But the twist on Brownson was Schlesinger’s own: He boldly argued that the radical agitator’s writings and orations anticipated ideas found in Marx’s work that came nearly a decade later.

But despite being drawn to the Progressives’ radical historical interests, Schlesinger did not embrace their politics. In fact, for someone coming of age amid the upheaval and suffering of the Depression, he was remarkably uninterested in politics, spending most of his college years—and large sums of his father’s money—on films, late-night drinking, and jazz clubs. (A whole chapter of his memoir—“Harvard College: What I Enjoyed”—is dedicated to documenting his budding epicureanism.) When he did engage with his era’s heated controversies, he often showed a strong contempt for his peers’ “undue political activism.” After a nationwide student “peace strike” was organized in 1935, Schlesinger applauded the “young Princetonians [who] established the Veterans of Future Wars.” When another student group formed to repeal a loyalty oath imposed on Massachusetts college professors, he confessed in his journal: “Those who want the barricades can have them but I don’t.”

Donald Trump’s cruel and chaotic second term is just getting started. In his first month back in office, Trump and his lackey Elon Musk (or is it the other way around?) have proven that nothing is safe from sacrifice at the altar of unchecked power and riches.

Only robust independent journalism can cut through the noise and offer clear-eyed reporting and analysis based on principle and conscience. That’s what The Nation has done for 160 years and that’s what we’re doing now.

Our independent journalism doesn’t allow injustice to go unnoticed or unchallenged—nor will we abandon hope for a better world. Our writers, editors, and fact-checkers are working relentlessly to keep you informed and empowered when so much of the media fails to do so out of credulity, fear, or fealty.

The Nation has seen unprecedented times before. We draw strength and guidance from our history of principled progressive journalism in times of crisis, and we are committed to continuing this legacy today.

We’re aiming to raise $25,000 during our Spring Fundraising Campaign to ensure that we have the resources to expose the oligarchs and profiteers attempting to loot our republic. Stand for bold independent journalism and donate to support The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editorial Director and Publisher, The Nation

On this, he diverged considerably from his father and his father’s generation of historians. While the Progressives championed how working Americans made their own history, and while they often at considerable risk to their own careers involved themselves in radical causes and movements, little Arthur identified with those in power—in particular, Roosevelt and the New Dealers. “So far as I was concerned,” he later recalled, “the New Deal was the main event, Marxism a sideshow, irrelevant to the American future.”

Writing never presented a problem for Schlesinger. Between his 1939 debut on Brownson and his 50th birthday, he published 11 books—many 400 to 500 pages long—and hundreds of articles and book reviews. In the 40 years that followed, he continued the pace, publishing seven more books and writing thousands of journal entries, which two of his sons, Andrew and Stephen, posthumously published in 2007.

But what made Schlesinger’s output so remarkable was not only the quality of his prose or how he synthesized other scholarship into bold new glosses. It was also that he wrote so much, and so well, while juggling demanding day jobs and moonlight responsibilities. Between his graduation from college and 1963, when he left the White House, Schlesinger was rarely just a historian. During the Second World War, he was a propagandist and intelligence analyst, working for the Office of Wartime Information and the CIA’s precursor, the Office of Strategic Services. In the early postwar years, he postponed a Harvard appointment to work as a journalist in Washington, where he wrote a series of well-circulated articles and was an active member in a variety of liberal anticommunist fronts, including Americans for Democratic Action and the Congress for Cultural Freedom. (In an uncharacteristically underdeveloped aside, Aldous notes that in these years Schlesinger also was “still on the books of the CIA as a consultant.”)

But Schlesinger’s main distraction was electoral politics, especially Democratic Party politics. Through the relationships he cultivated in postwar Washington, he found himself enlisted in Averell Harriman’s bid for president in 1952, then Adlai Stevenson’s in 1956, and then—most fatefully—in Kennedy’s 1960 campaign, for which he was awarded a post in the White House.

Throughout these years, Schlesinger often hid his political ambitions behind his scholarly bow ties and credentials. But a considerable amount of cunning—and sometimes outright deception—paved his way from Harvard Yard to the White House. When he jumped from Harriman’s sinking ship to Stevenson’s more promising one, he shared, as Aldous tells us, “inside knowledge about Harriman to help Stevenson knock him out of the race.” And when he ditched Stevenson for JFK, he recruited a group of fellow Stevenson intellectuals—John Kenneth Galbraith and Henry Steele Commager among them—to publicly endorse Kennedy and thereby prevent old Adlai from considering a third run.

Schlesinger’s betrayals of Harriman and Stevenson stung both men greatly. They also haunted Schlesinger, who knew how much he owed to their early confidence in him. (Of his Stevenson betrayal, he confessed: “I felt sick about it, and still feel guilty and sad.”) But Schlesinger also came to believe that his choices were justified: If liberals were to be close to power—if they were one day to be in power—they had to engage in its brutal “power realities.”

In a diary entry distinguished by its novelistic flourishes, Schlesinger recorded a conversation he had with Harriman in 1978, when the two men sought out a tentative rapprochement. Observing a framed portrait of FDR hanging in Schlesinger’s entryway, Harriman “paused for a moment and said, ‘You know why he was such a great President?… Because he did not yield to feelings of personal loyalty. He picked men, gave them jobs to do, gave them plenty of discretion. If they did the job, well, fine; if not, he cut them off without a second thought.’” Sensing that Roosevelt was not Harriman’s only target, Schlesinger cited Emerson: “whatever else could be said for or against him, everyone had to admit that Napoleon ‘understood his business.’” One suspects Schlesinger would have defended his own actions with a similar retort: that he, too, understood his business.

But it wasn’t just from his experiences in politics that Schlesinger began to develop a better understanding of the power politics required of American liberals; it was also through his historical scholarship. What Schlesinger admired about the “tough-minded Jacksonians” like George Bancroft and Nathaniel Hawthorne and the young cadre of New Dealers who became the protagonists of The Age of Roosevelt was that they represented the ideal of the “action-intellectual”: They may have been driven by a set of commitments, but they recognized that American politics was ultimately a war of will more than one of ideas.

This was perhaps most explicit in the narrative structure of The Age of Roosevelt. After tracking the failure of the old laissez-faire liberalism in his first volume, and the rise of a new idealistic liberalism in his second, Schlesinger turned to the “battle of the century” between the New Dealers and their opponents. In doing so, he sought to vindicate FDR’s more ruthless tactics. Faced with a hostile Supreme Court and an agitated business class, Roosevelt threatened to pack the Court. He and his advisers waged a war against their critics from inside the White House and decried the business community as “the enemy within our gates.” Roosevelt, Schlesinger wrote, chose to “take a progressive stand and force the fight on that line.”

Get unlimited access: $9.50 for six months.

This was largely the kind of class war that his father and the Progressive historians had celebrated. But while the main combatants for the Progressives were hardworking Americans and elites, Schlesinger saw the fight as between those already in power: FDR and the New Dealers, who wielded political power, and those, like Wendell Willkie and William Randolph Hearst, who wielded economic and cultural power. The battle of the century was on; it just had very little to do with most Americans. “All politics,” Schlesinger argued in The Age of Roosevelt’s third volume, “begins and ends with power.”

Schlesinger’s view of American politics as a brutal scramble for power was the core of perhaps his most famous book, The Vital Center. First and foremost a work of Cold War polemic against the threat of communism abroad, the book also directed its ire to liberals and the left at home. Inspired by the “Augustinian forebodings” of Perry Miller and Reinhold Niebuhr, Schlesinger argued that liberals’ and socialists’ faith in human progress and reason had blinded them to the fallibility and tragedy baked into all forms of human activity. No society was perfectible because no individual was, and no set of liberal or egalitarian politics was realizable without a more hardheaded view of politics and political morality. To beat back liberalism’s enemies required ideological flexibility and a willingness to sacrifice principle for power.

Of course, many liberals and socialists had already come to this realization during the Depression and the Second World War, forming “popular fronts” that transcended ideological differences in order to face down the economic and geopolitical crises of their age. Likewise, many of the liberal and left-wing intellectuals Schlesinger criticized—figures like John Dewey and the Fabians—subscribed to a view of politics that was far from doctrinaire and that was defined by an instrumentalism that made experience and consequence key measures of success (an instrumentalism that, as Randolph Bourne noted, also proved willing to sacrifice ideals for power).

But Schlesinger wasn’t writing history; he was writing for a cause—a vital liberal centrism that drew its “strength from a realistic conception of man” and that “dedicated itself to problems as they come.” This was not a defense of the ideological center as Clinton and the New Democrats imagined; it was a call to arms for liberals, social democrats, and, yes, socialists—in The Vital Center, Schlesinger writes with admiration of Karl Kautsky, Eugene Debs, and Leon Blum—to honestly reckon with what was required of them. His vital centrism was, therefore, not a politics of moderation but a politics of war. “It believes in attack,” he noted near the book’s end, “and out of attack will come passionate intensity.”

Part of Schlesinger’s militancy, one suspects, came from the fact that he had spent a lifetime living down the taunt of being an “egghead.” Part of it was also a matter of wanting to be liked by those who perceived the world as a set of power relations (he assiduously courted people like Henry Kissinger, and it wasn’t lost on Schlesinger that Kennedy, who had been two years behind him at Harvard, had ignored him throughout their undergraduate years). But it was also because Schlesinger had come to believe that liberals had been hampered by a set of dogmas—a faith in human nature, in historical progress, and in the possibilities of collective action—that had been discredited by the first half of the 20th century. If they were to succeed in its second half, they’d have to embrace the responsibility and sometimes the sins of power.

Early in The Vital Center, Schlesinger quotes Virginia congressman and slaveholder John Randolph of Roanoke: “power alone can limit power.” Schlesinger certainly approved of little else in Randolph’s politics—among other things, Randolph lamented the loss of a permanent landed gentry in America—but on this statement he was in clear agreement.

One of the dangers of Schlesinger’s vital center was that, over the long haul, its realism and power politics could become ends in themselves. This was Bourne’s warning about the instrumentalism practiced by many of Dewey’s acolytes during the Progressive Era and in the lead-up to the First World War, and it was also the central lesson of North Atlantic politics since the 1980s, when out-of-power “Third Way” liberals, social democrats, and socialists disavowed their parties’ egalitarian programs in favor of policies—deregulation, regressive tax schemes, free-trade agreements, means-tested welfare—that they believed would help them win over conservative voters.

Schlesinger may not have liked this new Third Way; his way was that of a robust social democracy that could stand between communism and laissez-faire capitalism. But the liberal power politics that undergirded his vital center was always at risk of mission creep. Tactics could become strategy and power could become the key measure by which liberals and the left assessed themselves—which is exactly what happened with the New Democrats and the rise of a new generation of center-left politicians in Europe. Prioritizing immediate electoral gains over long-term goals, they abandoned the state-centered rhetoric that kept the center of liberal democracies from creeping back to the extremes of the free–market right. By heralding risk-taking entrepreneurs, flexible labor policies, and deregulation, they also undermined the very conditions upon which their base had been composed and sustained. As a theory of politics, their strain of vital centrism proved highly effective in the short term and devastating over the long: It was full of Pyrrhic victories in which center-left politicians won on platforms that undercut their parties’ future.

To his credit, Schlesinger began to recognize the risks by the late 1960s and early 1970s. After three heady years in the Kennedy administration—which he recorded in A Thousand Days—he became a bitter critic of the Johnson administration as it shifted away from its early Great Society programs into the brutality and morass of the Vietnam War. (“The fight for equal opportunity for the Negro, the war against poverty, the struggle to save the cities, the improvement of our schools,” he lamented in 1967, were all “starved for the sake of Vietnam.”) Likewise, the craven power plays of Richard Nixon and Schlesinger’s old dining partner, Henry Kissinger, caused him to grow ever more wary of the realist presidential politics that he’d once heralded.

The frustration and anger that Schlesinger felt toward the Johnson and Nixon administrations also directed his attention to a new project: an effort to understand what had gone wrong with the American presidency. Published as The Imperial Presidency in 1973, the book rivaled almost all of his early histories in its originality and ability to synthesize historical scholarship. It also far surpassed them in its temporal scope. While his earlier work had zoomed in on moments of heroic presidential action—such as the Jacksonian and New Deal years—he now told a much darker and longer story about American power: how, starting with the early Republic, a pattern of “presidential usurpation” had caused the executive branch to colonize the powers of other branches of government.

The Imperial Presidency also proved to be Schlesinger’s most self-critical work. He didn’t pull any punches when it came to reassessing the excesses of his presidential heroes. In it, Jackson came off as more of a tyrant than a radical democrat, while Roosevelt’s use of the White House to wage a war against his critics and his threat to override the courts looked ever more sinister in the years after Nixon and Watergate. So, too, in the wake of Vietnam, did Kennedy’s expansion of executive privilege when it came to national security. “Alas,” Schlesinger acknowledged, “Kennedy’s action [during the Cuban missile crisis] should have been celebrated as an exception,” not “enshrined as a rule…. This was in great part because it so beautifully fulfilled both the romantic ideal of a strong President and the prophecy of split-second presidential decision in the nuclear age…. But one of its legacies was the imperial conception of the Presidency that brought the republic so low in Vietnam.”

Schlesinger’s work in his later years was mixed. Much of his scholarship after The Imperial Presidency tended to circle around conclusions made in his early career or, worse, surrender to the temptations of hagiography, such as in Robert F. Kennedy and His Times. Once living in New York, he also spent perhaps too much time basking in his newfound celebrity, earning the nickname “the swinging soothsayer” from Time magazine, and carousing and drinking with the likes of Norman Mailer, Andy Warhol, Lauren Bacall, Anjelica Huston, and Shirley MacLaine. (“I find great pleasure in intelligent actresses,” he confided in his diary.)

Aldous does not focus on these years with the same level of intensity or care for detail that he directs toward Schlesinger’s earlier years, dedicating only 50 or so pages to the last four decades of his life. One can understand why: Schlesinger’s salad days ran parallel to the heyday of mid-20th–century liberalism; they were more exciting times, at least for Schlesinger. But one suspects that Aldous, a contributing editor to The American Interest, is also more interested in tracking liberal realism’s rise instead of its fall.

Nonetheless, despite the brevity of Aldous’s last chapters, one does get the sense that Schlesinger was trying, in his later years, to come to terms with the bellicose liberalism he’d championed much of his life. Something had gone terribly wrong with his vital center, both at home and abroad. Some battles may have been won, but the wars—both metaphoric and literal—had almost all been lost. Vietnam and the Cold War helped bankrupt the good created by the second wave of social-democratic policies enacted under Kennedy and Johnson. The Democrats’ ideological flexibility and triangulations may have gotten them back into the White House, first in the late ’70s and then in the 1990s—but at what cost?

Thinking about what he got wrong in The Vital Center, Schlesinger confessed in his journal that he’d celebrated the propulsive economics of the postwar years too uncritically—and without thinking about those left behind. Likewise, he admitted, “the Cold War and the obvious cruelties of communism made us all tend to defend our system as a system. And it is undeniable that the system as such tolerates a continuing set of injustices and evils.”

Schlesinger may have happily dined with the Clintons, but Clinton’s policies during his first term—welfare reform, in particular—“infuriated and depressed” him, and by 1996 he had “resolved to stop defending Clinton in the future.” Unlike FDR and the New Dealers, who took a progressive stand and forced the fight on that line, Clinton and the New Democrats allowed the center of American politics to move to the right.

Schlesinger always paired the moral pessimism of Augustine and Niebuhr with a surprising amount of faith in the possibilities of history. It was not that he believed social progress was inevitable, but that he liked to emphasize the good in the midst of the bad. This historical sanguinity was what led him to elide the racism and violence of Jacksonian democracy and to subdue any skepticism he might have had about the opportunism of both FDR and JFK. It was this “politics of hope”—a phrase that he used to title a book on the New Frontier—that also allowed him to argue in the Reagan years that American history cycled between a politics of progress and affirmative government and one of regress and chaos. In the face of all that was rotten, the good may yet still arise. Schlesinger never abandoned this politics of hope, but he did begin to worry about the power politics and realism upon which it relied.

Two of his last pieces before his death in 2007 seemed to capture his growing despair. Both were on jaded liberal action–intellectuals: the editor and novelist William Dean Howells and the historian Henry Adams. Having spent the first half of their lives in the thrall of Republican reform, they had, by the late 19th century, found themselves repulsed by its corruption and excesses. Howells felt particularly anguished over the four Haymarket anarchists who were hanged for crimes they didn’t commit (a fifth killed himself in jail). Adams, whose grandfather and great-grandfather had been presidents, soured on the crude intertwining of money and politics in Gilded Age Washington and abandoned the city and its politics to teach history at Harvard.

Both spent the last years of their lives increasingly distraught over the trajectory of their own liberal ideals. After Haymarket, Schlesinger wrote, Howells “tried to get other writers to join in condemning a palpable miscarriage of justice,” but “no one came along…and [he] was denounced by the respectable press.” Of Adams’s disenchantment, Schlesinger was more succinct: “What had gone wrong?”

David MarcusTwitterDavid Marcus is the literary editor of The Nation and has contributed essays and reviews to The New Republic, n+1, Bookforum, and Dissent. He holds a PhD in history from Columbia and previously was the co-editor of Dissent.