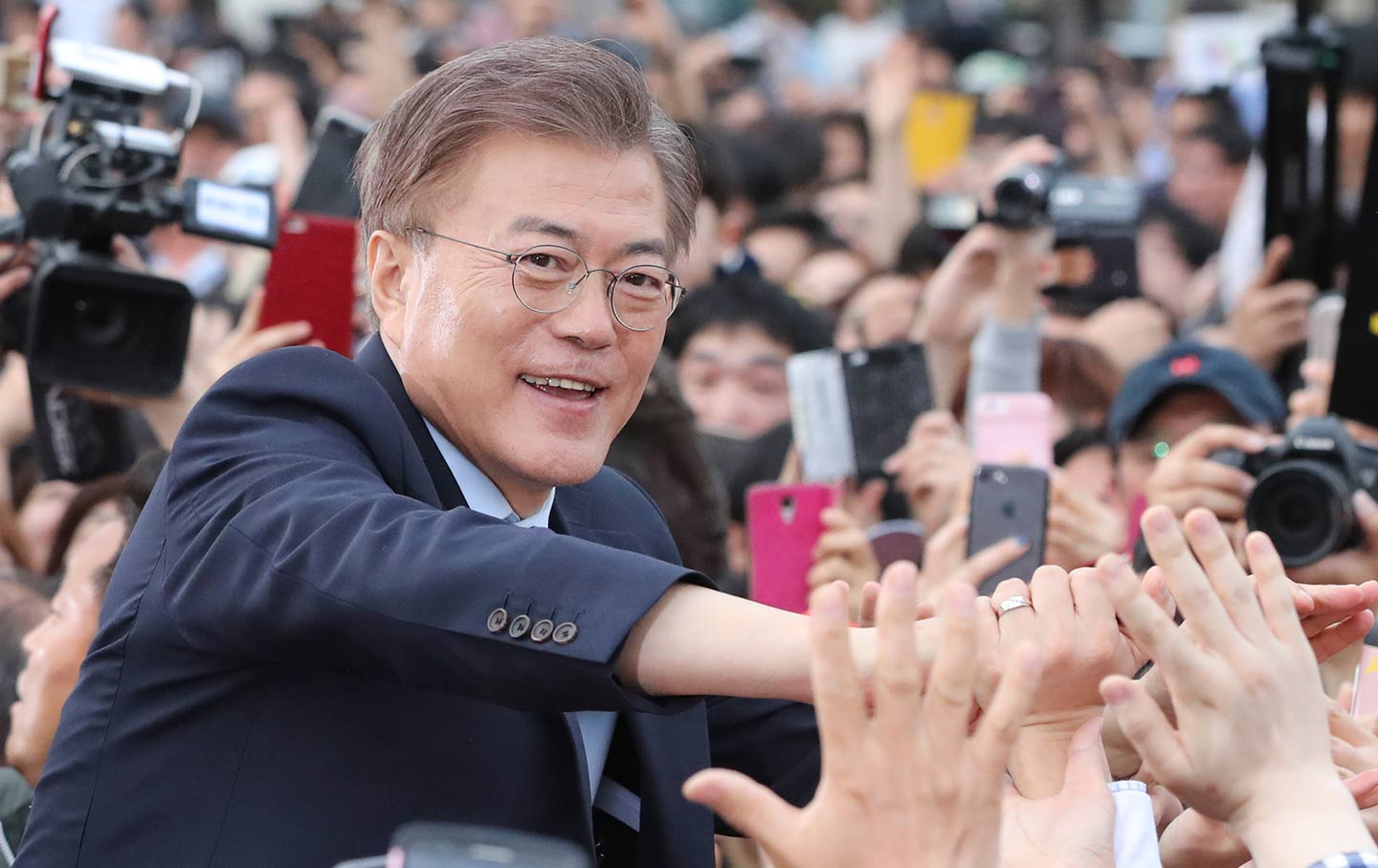

South Korean progressive presidential candidate Moon Jae-in is greeted by his supporters in Goyang, May 4, 2017.(AP Photo / Lee Jin-man)

Gwangju, South Korea—On May 2, Moon Jae-in, the Korean politician who is expected to win next Tuesday’s presidential election here, issued a stern warning to the United States. Pointing to the escalating tensions between North Korea and the United States, he told The Washington Post that South Korea must “take the lead on matters on the Korean Peninsula.” Seoul, he added, “should not take the back seat.”

Moon, a progressive politician with deep roots in South Korea’s left, has repeated these words throughout his campaign. They signal his wish to change the dynamics of US-South Korean relations and meet his country’s desire for a more independent foreign policy. In particular, he wants to use economic and political incentives to ease tensions with the North—a position anathema to many in Washington.

The US government, Congress, and the Pentagon should listen to Moon and his voters. Over the past two months, President Trump has done more to alienate South Korea than any American leader in the past 40 years. If Trump and the American politicians and pundits who support his militaristic approach to North Korea aren’t careful and continue to ignore this country’s wishes, they could spark the most serious wave of anti-Americanism in the South since 1980.

That was the year the Carter administration—which had made human rights the centerpiece of US foreign policy—helped South Korea’s military put down a citizens’ uprising in this city against a group of generals who had seized power to stave off the country’s first “democratic spring.”

As I first revealed in 1996, the White House made that decision knowing that hundreds of people had been massacred by Korean special forces only days before. The damage to US-Korean relations from this episode lasted for years, and shaped the attitude of many South Koreans toward the United States.

To be sure, a Gwangju-like repression is unlikely to ever happen again in South Korea. And the United States learned long ago that its support for military strongmen in Seoul seriously eroded its moral authority in Korea. But when it comes to national security issues, US officials have long preferred dealing with South Korea’s right wing.

During the past two American administrations, US officials embraced the hard-line policies toward North Korea taken by former president Park Geun-hye, who was recently impeached after months of candlelight vigils involving millions of angry citizens; she is now in jail, awaiting trial on charges of corruption and abuse of power. The US government was equally supportive of Lee Myung-bak, Park’s conservative predecessor.

But today, Park’s and Lee’s policies are widely reviled in South Korea for stoking the current tensions with Pyongyang. In his campaign, Moon has picked up this theme, urging a return to the “Sunshine” policies once embraced by South Korea’s previous progressive presidents, Kim Dae-jung and Roh Moo-hyun. The remnants of Park’s right-wing party have responded with vicious red-baiting ads that portray Moon and other left-wing candidates as tools of North Korea, according to the Twitter feed “Ask a Korean.”

But with Moon entering Tuesday’s snap election with a massive lead in the polls (42.5 percent to 18.6 percent over his nearest rival, the centrist Ahn Cheol-soo), he will almost certainly assume the presidency. When the numbers for the other leftist candidate in the race, the labor activist Sim Sang-jung, are counted, the left could take 49.7 percent of the vote—an astonishing total in a country where conservatives have ruled since 2008 and at a time of intense tensions with communist North Korea. This election, therefore, will force Trump to deal with a South Korea very different from the one led by conservatives over the past decade.

Trump’s mishaps with the South began in mid-April, when he said he was deploying an “armada” to Korean waters to carry out a possible pre-emptive strike on Kim Jong-un’s North Korea. South Korean politicians of all stripes demanded that Seoul be consulted on any such action—and then learned, as Americans did, that the carrier group was nowhere near the peninsula. This was a humiliating blow, and many people felt used and manipulated.

Then came Trump’s silly tweet that Korea once belonged to China; it, too, was challenged and denounced across the political spectrum. But the most insulting move came on April 25, when the Pentagon—using North Korea’s stepped-up missile tests as an excuse—unilaterally deployed equipment for the unpopular Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) antimissile system on a corporate golf course in North Gyeongsang Province.

The Pentagon did this over the objections of many politicians, including Moon, who has been saying for months that he wants the next government to make the decision on THAAD. He called the move a fait accompli, telling reporters that THAAD “should not be rushed ahead” of the elections. Moon and many other politicians were further incensed when Trump demanded that South Korea pay for the $1 billion system. A Korea Times banner headline on May 2 told the story: “THAAD billing to strain ROK-US alliance.”

Public anger over THAAD was deepened by photographs of American GIs taking video of the scene as riot police pushed and beat thousands of local residents, many of them elderly, trying to block the deployment. Signs at the protests—which have not let up—symbolized the growing ferment. A photograph of one sign reading “Hey! USA! Are you Friends or Occupying Troops?” was splashed across the front pages of many newspapers. They are the most overt expression of anti-American feeling I’ve seen since I was a reporter here in 1985.

But Trump’s actions and attitudes aren’t really new. They underscore a deep-seated problem with American policy in Korea: a refusal to see South Korea as an independent nation with a will, a spirit, and interests of its own.

The attitude goes back to 1945, when the United States accepted the surrender of Japanese forces in the southern part of the Korean Peninsula (by mutual agreement, the Soviet Union did the same in the north). In contrast to the US occupation of Japan, which was allowed to rule through its existing state structure, the US Army in Seoul imposed a military government on Korea, which had been a victim of Japan’s colonial rule. This set up a dynamic that would prove to be tragic.

As part of America’s shift into the Cold War, the US military commanders in South Korea chose to work with Koreans who had collaborated with the Japanese Empire in its own fight against communism during World War II. Koreans who opposed these policies and sought to unify with the north were jailed and ruthlessly suppressed.

From 1947 to 1949, the US military even presided over a brutal counterinsurgency campaign against leftist nationalists on Jeju-do, an island off the southern coast, at the cost of over 30,000 lives—nearly one-fifth of the population. The internal conflicts in the south laid the seeds for the creation of separate states in 1948, and was a key factor in the war that broke out across the peninsula when North Korea invaded South Korea in June 1950.

Only eight years after that terrible war, South Korea experienced its first military coup when Park Chung-hee, a general trained by the Japanese Imperial Army during World War II, overthrew an elected government in 1961 in a military coup and was immediately recognized as South Korea’s leader by the Kennedy administration.

Over the next 18 years, Park presided over a vast police and torture state. But he also set out to industrialize South Korea, which grew during his rule into a powerhouse in garments, shoes, steel, shipbuilding, automobiles, and, eventually, electronics (Park Geun-hye, the recently deposed president, was the dictator’s daughter). He ruled with an iron fist until he was assassinated in the midst of large-scale worker and student unrest in 1979.

Throughout Park Chung-hee’s rule, the South Korean military remained an adjunct of the Pentagon. During the Vietnam War, at Washington’s request, Park sent thousands of Korean troops to fight alongside American forces (among them was Chun Doo-hwan, the general who seized power in May 1980 and ordered his special forces into Gwangju). Under a joint command created in 1978, a US general still has operational control over the South Korean army in times of war.

These Cold War dynamics created a “big brother–little brother” relationship in which US officials—even today—disdainfully treat South Korea as a junior partner in the alliance. This attitude has rubbed off on the US press, which often covers North Korea without even mentioning South Korea, its complex mix of politics, and the terrible impact a war would have on the South. The country’s insignificance to the US national-security elite has been further amplified by Trump’s exclusive consultations with Japan’s Shinzo Abe and China’s Xi Jinping regarding North Korea.

Trump’s calls to the Japanese and Chinese leaders led one South Korean newspaper to accuse the United States of “freezing out Seoul.” They also prompted Moon Jae-in’s demand, in his Washington Post interview, for South Korea to be the driver for change on the peninsula. He is also pushing for a quick recovery of wartime operational control from US forces. “We will take charge of our defense ourselves [for] all intents and purposes,” he declared in April.

Most reporters, however, have missed how Moon has also taken sides on the volatile issue of Gwangju.

Two weeks ago, I heard Moon speak at a campaign rally not far from the site of the 1980 massacre. At one point, with his fist raised high, he joined the crowd in singing “March for the Beloved,” the famous Gwangju anthem to the hundreds of local citizens killed by martial-law forces during the 1980 uprising. The song, frequently sung at political gatherings here, has been denounced by rightists and the current ruling party as pro–North Korean.

But with his gesture, Moon sent a strong signal that a South Korea under his presidency will honor the spirit of Gwangju and stand up to America when it’s wrong, as it was when it sided in 1980 with the generals instead of Gwangju’s citizens.

As I reported last fall, many US officials, particularly at the Pentagon and its associated think tanks, have been uncomfortable with the thought of Moon or anyone else on the South Korean left taking power. They better wise up, because the Korea they once knew is gone forever. Even as tensions mount with North Korea, the United States—unless it shows greater respect for the South Korean people, its elected leaders, and their vibrant democracy—could lose one of the best friends it ever had.

Tim Shorrock is currently working at Gwangju’s 5.18 Archives to help document the US role in the 1980 uprising.

Tim ShorrockTwitterTim Shorrock, who has been reporting on Korea for The Nation since 1983, is a Washington, D.C.–based journalist and the author of Spies for Hire: The Secret World of Intelligence Outsourcing.