When Aracely Calderon, a naturalized US citizen from Guatemala, went to vote in downtown Phoenix just before the polls closed in Arizona’s March 22 presidential primary, there were more than 700 people in a line stretching four city blocks. She waited in line for five hours, becoming the last voter in the state to cast a ballot at 12:12 am. “I’m here to exercise my right to vote,” she said shortly before midnight, explaining why she stayed in line. Others left without voting because they didn’t have four or five hours to spare.

The lines were so long because Republican election officials in Phoenix’s Maricopa County, the largest in the state, reduced the number of polling places by 70 percent from 2012 to 2016, from 200 to just 60—one polling place per 21,000 registered voters. Previously, Maricopa County would have needed federal approval to reduce the number of polling sites, because Arizona was one of 16 states where jurisdictions with a long history of discrimination had to submit their voting changes under Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act. This part of the VRA blocked 3,000 discriminatory voting changes from 1965 to 2013. That changed when the Supreme Court gutted the law in the June 2013 Shelby County v. Holder decision.

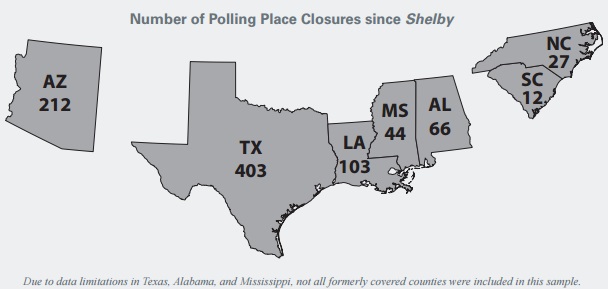

The polling place reductions in Maricopa County were a glaring example of a disturbing trend. The Leadership Conference for Civil Rights surveyed 381 of the 800 counties previously covered by Section 5 where polling place information was available in 2012 or 2014 and found there are 868 fewer places to cast a ballot in 2016 in these areas. “Out of the 381 counties in our study, 165 of them—43 percent—have reduced voting locations,” says the important new report.

While new statewide voting restrictions like voter-ID laws and cuts to early voting in places like Texas and North Carolina have received national attention, the polling place closures could have as big of an impact in 2016—the first presidential election in 50 years without the full protections of the VRA.

Popular

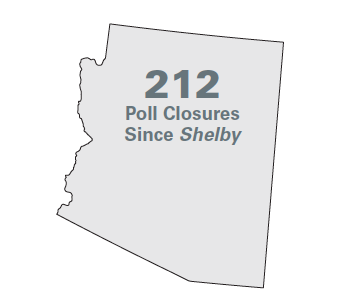

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →Arizona, the poster child for voting problems in the primary, closed the highest percentage of polling places in the study. “Almost every county in the state reduced polling places in advance of the 2016 election and almost every county closed polling places on a massive scale, resulting in 212 fewer polling places,” says the report (emphasis in original). Tucson’s Pima County—the second largest in the state, which is 35 percent Latino and leans Democratic—“is the nation’s biggest closer of polling places,” from 280 in 2012 to 218 in 2016.

Many of these counties have been hot spots for voting discrimination. Cochise County, on the Mexico border, which is 30 percent Latino, was sued by the Justice Department in 2006 failing to print election materials in Spanish or have Spanish-speaking poll workers, in violation of the VRA. Today, the county “is the nation’s biggest closer by percentage,” having shuttered 63 percent of its voting locations since Shelby. There will be only 18 polling places for 130,000 residents in 2016, down from 49 polling places in 2012.

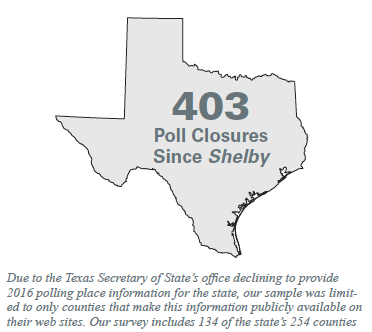

Texas has closed more than 400 polling places, more than any other state in the study. “Almost half of all Texas counties in our sample closed polling places since Shelby, resulting in 403 fewer voting locations for the 2016 election than in past years,” according to the Leadership Conference.

Medina County, a heavily Republican area in South Texas, closed a polling place in the town of Natalia, which is 75 percent Latino and the only Democratic-leaning part of the county. “We’ve had a polling place for at least the last six decades,” Emilio Flores, a local activist and registered Republican, told me. When Flores asked the county elections administrator, Patricia Barton, how low-income and disabled Latino voters were supposed to vote without a polling place in their town, he said she told him, “If you think it’s such a big issue, why don’t you shuttle them yourself?” Last week the county commission approved a polling place in Natalia for Election Day after local activists like Flores raised alarms, but Medina County will have only eight polling places in 2016, down from 14 in 2012.

We’re already seeing the impact of polling place closures during early voting in states like North Carolina. The state cut a week of early voting for 2016, which was overturned as discriminatory by a federal court, but many GOP-controlled counties still limited early voting hours and locations, leading to four hour lines in cities like Charlotte and a 16 percent decrease in black turnout compared to 2012. Black turnout decreased the most in the 17 counties that had only one polling site for the first week of early voting.

Thirty percent of the 40 counties in North Carolina that had to approve their voting changes with the federal government closed polling places on Election Day. The Leadership Conference spotlights the impact:

Cleveland County, which is on the outer edge of the Charlotte metropolitan area, is a textbook example of a change that would have received enhanced scrutiny under Section 5. In the 2012 election, voters in Cleveland County were served by 26 polling places; in 2016, they’ll only have 21—a drop of 19 percent. In the summer of 2014, the county’s board of elections merged five of these voting locations into two in the city of Shelby—which is 40 percent Black—over opposition from the Cleveland County NAACP. Rev. Dante Murphy, the Cleveland County NAACP president, said, “We know that this is part of a bigger trend—a movement to suppress people’s right to vote.”

There are a variety of reasons for the polling place closures. Most counties cite budget shortfalls. Some said they couldn’t comply with the Americans with Disabilities Act. A few states, like Arizona and Texas, have switched to “vote centers,” where there are fewer polling places but county residents can vote anywhere they like, rather than at an assigned polling place. This model works well in some places, but was a disaster in Maricopa County during the primary, when officials allocated far fewer polling places than necessary.

Still, it’s impossible to ignore that polling places are being closed on a major scale in states with a very ugly history of suppressing voting rights, like Louisiana and Mississippi. “Since Shelby, 61 percent of Louisiana parishes have closed a total of 101 polling places since 2012,” says the report. “About 34 percent of all Mississippi counties surveyed have closed polling places since Shelby, resulting in at least 44 fewer polling places for the 2016 election.”

In June 2013, Percy Bland was elected as the first black mayor of Meridian, Mississippi, where the Ku Klux Klan abducted the civil rights workers James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Mickey Schwerner during Freedom Summer in 1964. A month after Bland’s election the Supreme Court gutted the VRA, and in 2015 the majority-white board of elections in Lauderdale County closed seven polling places over objections from the mayor. That included eliminating a polling place at the historic Mt. Olive Baptist Church, a major site during the civil-rights movement, as the place where the singer Pete Seeger announced that the bodies of Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner had been discovered after they were missing for 44 days. “In an effort to honor the legacy of those who paid the ultimate sacrifice in order that we enjoy our civil rights, we proudly offer our historic facilities [as a polling site],” said church spokesman Ronald Turner.

“Things have changed dramatically” in the South, Chief Justice John Roberts wrote in the Shelby decision. “The tests and devices that blocked ballot access have been forbidden nationwide for over 40 years.” But as we’re seeing clearly in 2016, the states previously covered by the VRA keep finding new ways to undermine the right to vote.