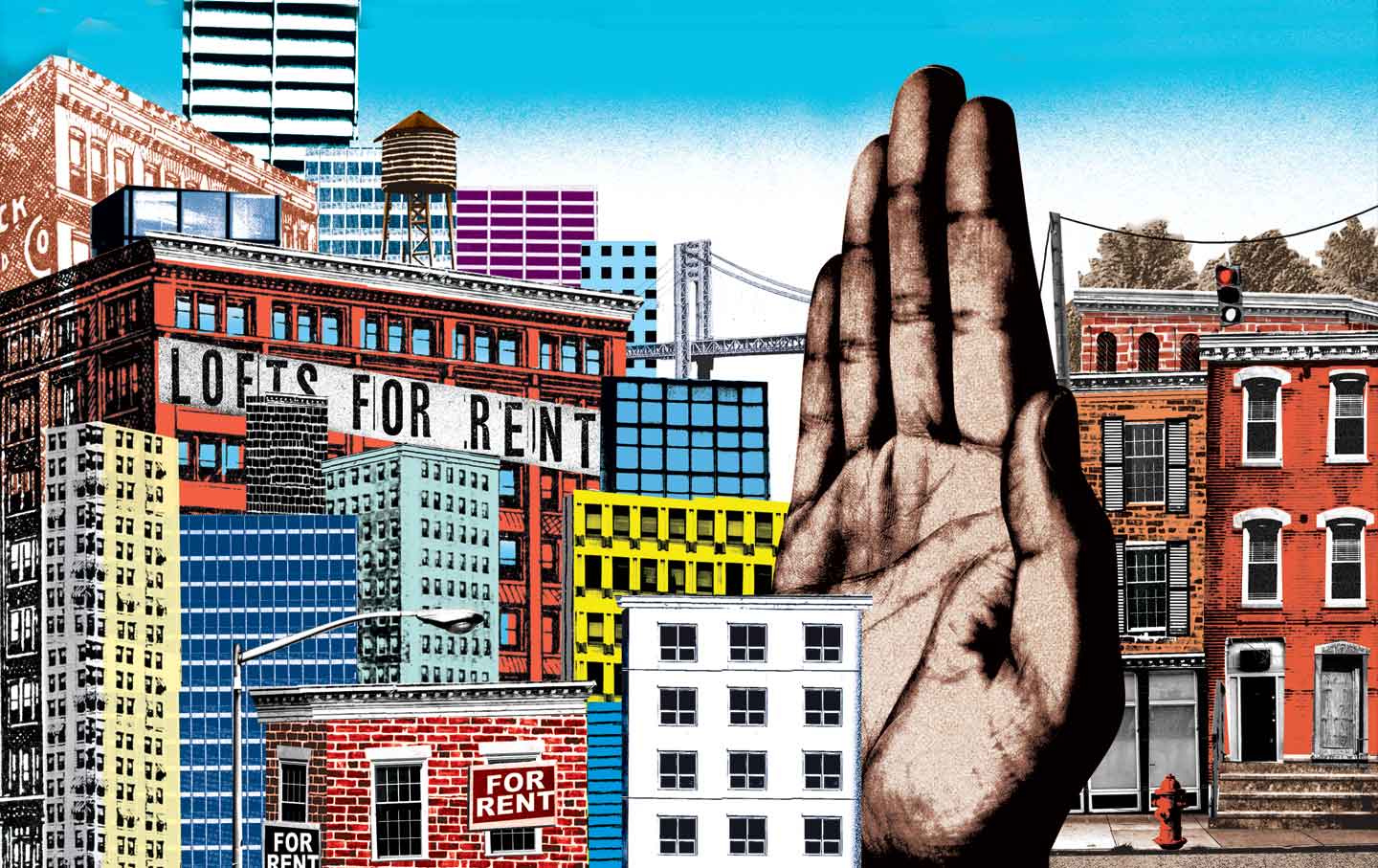

Illustration by Doug Chayka.

The giant sign fluttering in the wind read “Espinal, Don’t Gentrify E NY!” Rachel Rivera, a resident of Brooklyn’s East New York neighborhood, held up one end of the sign; Lorna Blake, also of East New York, held the other. They were marching on April 13 to the district office of New York City Councilman Rafael Espinal with other members of New York Communities for Change (NYCC) as well as Make the Road New York and several building-trades unions. Their mission: to press Espinal into voting against a rezoning plan that they feared would accelerate gentrification. As if to underscore this point, white hipsters occasionally stopped to snap iPhone photos of the protest.

Rivera wore a bright-orange NYCC T-shirt under a parka and over sweats—she’d dressed comfortably, she said, for the main part of the action. Once at Espinal’s office, she and several others—NYCC executive director Jonathan Westin; Bertha Lewis, founder of the Black Institute; and seven NYCC comrades—sat down and refused to move. “They say, ‘Go away!’ We say, ‘No way!’” the crowd chanted as police swept in and handcuffed the protesters. Espinal was nowhere to be seen.

That was on Wednesday. On Thursday, fresh from jail, Westin and NYCC members were in the streets again, this time as part of a nationwide day of action in the Fight for $15, the movement that NYCC had launched with the Service Employees International Union (SEIU) in 2012. And on that very same day came the announcement that, after a push from the NYCC-backed group the Hedge Clippers, New York City’s largest public-pension fund had voted to pull its money out of hedge funds. It was a particularly busy week for the community-based organization, one that served to highlight its evolving strategy for tackling the many ways that inequality is created and perpetuated, in New York City and across the country.

“We have a goal of trying to target a trillion dollars in capital,” Westin explained regarding the Hedge Clippers strategy. “Whether it’s real-estate capital, hedge-fund capital, JPMorgan Chase capital, or McDonald’s capital—we’re going after a trillion dollars in wealth from the 1 percent, from the richest white men on earth, and actually putting that money back into our communities.”

The Hedge Clippers, the Fight for $15, and the fight for affordable housing are the linchpins of NYCC’s strategy, three ways to answer the question of how to redistribute wealth and power back to working-class people of color. They’re examples of how one group is looking beyond the small, incremental campaigns typical of organizing in low-income communities of color, and aiming instead to actually challenge the structures of power in the city.

* * *

NYCC first appeared in 2010, but its origin extends back decades. It rose from the ashes of the Association of Community Organizers for Reform Now, which, at its peak, comprised a network of community groups under a national umbrella organization. ACORN had its roots in the welfare-rights movement of the 1960s and ’70s, and it fought for affordable housing, challenged predatory subprime lenders, and registered low-income people to vote. The organization was destroyed after right-wing “sting” artist James O’Keefe publicized deceptively edited videos purporting to show some ACORN members advising a “pimp” on the best way to conduct his criminal activities. Lawsuits vindicated the association, but too late; ACORN collapsed in 2010 after its funding evaporated. But around the country, former ACORN members have launched new groups, many of which have risen to prominence through their work alongside Occupy and the Black Lives Matter movement.

NYCC was shaped by those movements as well, said Westin, 32, who began organizing with ACORN more than 10 years ago. From Occupy came a sharpened analysis of power and capital; from the movement for black lives came the idea of reparations for the low-income people of color who make up NYCC’s membership. “The shared analysis is that it benefits the wealthiest people on earth to have people in powerless positions,” Westin said.

The typical approach of community organizations, Westin continued—especially those inspired by the legendary organizer Saul Alinsky—is to concentrate on winning locally, without attempting a broader critique of the real people in power. Mark and Paul Engler, in their book This Is an Uprising, describe it as a focus on local groups and a distrust of movements. But in the current political moment, NYCC and many other groups are thinking bigger, bolder, and more structurally.

“Right now, less-institutionalized forces like NYCC push the envelope of what’s possible,” said Bob Master, political director of the Communications Workers of America District 1. “When you take some risks, possibilities open up that you weren’t aware of.” One case in point: NYCC’s decision to enter a collaboration that, while not without its difficulties, launched a nationwide movement for higher wages.

* * *

In February of 2012, NYCC members rallied around a picket line outside the Golden Farm supermarket in Brooklyn’s Kensington neighborhood, demanding an end to wage theft and proper treatment for the supermarket’s immigrant workers. A marching band played alongside chanting workers; future Brooklyn Borough President Eric Adams and City Councilman Brad Lander addressed the crowd. The protest was part of a broader campaign in which NYCC partnered with Local 338 of the Retail, Wholesale, and Department Store Union (RWDSU) and the United Food and Commercial Workers to organize workers at several independent grocery stores. These businesses were small and often owned by people who were immigrants themselves; otherwise, the outline of what would become the Fight for $15 was visible in this campaign and another to unionize car-wash workers, in which NYCC teamed with Make the Road New York and RWDSU. In each case, a union provided the funding and training and took in the organized workers as members, while NYCC, sometimes alongside other groups with a base in the community, organized horizontally across an industry rather than shop by shop, aiming to change the practices in a sector rather than just a single store.

“People were working 80 hours a week and still not being able to afford an apartment,” Westin said. At the time, he was NYCC’s organizing director, and he and the group’s then–executive director, Jon Kest, thought that a bigger, broader campaign could work in the fast-food industry. They reached out to SEIU, which was looking for a national campaign to raise the issue of low wages to a new level, and a partnership was born, along with a plan for short, attention-grabbing strikes and a demand that would nearly double the workers’ wages.

The first fast-food strike kicked off on the morning of November 29, 2012. Hundreds of workers walked off the job for a one-day strike, demanding “$15 and a union.” Outside the Wendy’s in Brooklyn’s Fulton Mall, fuschia-haired Pamela Flood led the chants. “I’m out here just to show people that you don’t have to take $7.25 an hour for your hard work,” she told me then.

At the beginning of the campaign, NYCC and SEIU didn’t pitch the demand for $15 an hour and a union to elected officials. But as mayoral candidates and City Council members flocked to the picket lines to proclaim their support, it quickly became clear that workers were more likely to get $15 through legislation than through companies like McDonald’s ordering their franchisees to boost the wage. Yet there was a problem: New York City is barred by state law from raising its minimum wage, and Governor Andrew Cuomo staunchly opposed the hike.

As the campaign spread to more cities, SEIU began to take a higher profile in the media coverage, and the “days of action” tended to be coordinated across the country rather than tactically connected to any one city. This increased the potential for tensions in the movement, between the demands of a massive union and the needs of community organizations, which wield less power and often are dependent on the union for resources. (Around the country, Fight for $15 organizers have embarked on their own organizing campaign. Their demand: $15 and a union.)

“I think the challenges exist around the fact that this is new for everybody,” Westin said. “We’re really trying to work with unions to bridge the gap between what’s happening in the workplace and what’s happening with people on the ground—housing issues and schools issues and immigration issues.”

In 2014, Cuomo did an about-face and, one year later, took steps to raise the wages of fast-food workers and then of all New Yorkers. In his press conferences, Cuomo trumpeted the state’s “leadership” on the issue, and certainly New York’s workers were the first to demand $15 and a union. But by the time the governor got around to acting, the Fight for $15 had won raises in several major cities. For Cuomo, who is being investigated by US Attorney Preet Bharara, it was the perfect issue to seize on to win over some allies. (Indeed, SEIU spent some $500,000 on advertising thanking Cuomo for his support.)

In the end, this combination of creative tactics, a willingness to make bold demands, and a new partnership model helped to shape the national movement in the Fight for $15. And the national movement, in turn, transformed the $15 minimum wage from a utopian goal to a sure bet for politicians seeking to boost their progressive credentials. The success of the Fight for $15 and the Hedge Clippers has also burnished NYCC’s star, but the housing battle might be its toughest challenge yet.

Rachel Rivera discovered NYCC in 2012, after Hurricane Sandy destroyed her apartment. The group worked on Sandy relief from its Brooklyn office, and Rivera joined its campaign to secure relief funding. “I lost everything,” said Rivera, who was stranded with her six children in a hotel for more than a year. She finally found a place in East New York that she could afford, but as she acknowledges, “the seven of us in that one-bedroom apartment is not easy.”

Of late, it’s getting even harder, as Rivera has felt pressure from her landlord to move out. Her apartment is rent-stabilized, but, scenting the rezoning in the air, local landlords have been planning to sell to developers who will build new high-rises. Under an “inclusionary zoning” plan put forward by Mayor Bill de Blasio, those high-rises will have to set aside a number of apartments for low-income renters, but Rivera said she doesn’t make enough to qualify. (The plan’s definition of “affordable” is still beyond the reach of the poorest 20 percent of New Yorkers.) So Rivera joined the April 13 action to press her councilman, Rafael Espinal, to vote down the rezoning plan.

Despite these protests, the City Council passed the plan on April 20. “This is not an affordable housing plan, this is a gentrification plan,” Rivera said in a statement sent out by NYCC. “[F]ar more market rate units will be created than affordable units.”

From the moment de Blasio was elected mayor in 2013, it was clear that the fight for affordable housing was going to be rough. While de Blasio advanced the most ambitious program of any of the mayoral candidates—helping win the support of allies like NYCC—the need remains far greater than anything his plans deliver. And without federal investment in public housing, and with an often-hostile state government led by Governor Cuomo, his administration’s options for housing policy were limited from the start. But it was his appointment of Alicia Glen—former head of the Goldman Sachs Urban Investment Group—as the deputy mayor for housing and economic development that reminded community groups that they would have to keep up the pressure on de Blasio. The Real Affordability for All (RAFA) coalition, of which NYCC is an anchor member, came together shortly after the election and has pressed de Blasio and the state government on inclusionary zoning as well as rent regulations.

“We have members who used to live in Williamsburg who got pushed out here, people who did the trek from the Lower East Side to Williamsburg to Bushwick to East New York,” said Zachary Lerner, who coordinated the housing fight for NYCC. “This is where we had to put our foot down.” Lerner met with NYCC members and asked for their thoughts on keeping the community affordable; “affordable,” they replied, needed to mean affordable to them. They also wanted to make sure that construction jobs were accessible to local residents—a key reason the building-trades unions joined the coalition. The first march in East New York took place in May 2015, with NYCC calling for 50 percent of the new apartments to be rented at rates affordable to the surrounding community.

Despite the desire of NYCC and others to go beyond playing defense, they have largely been fighting on de Blasio’s terms. RAFA was criticized for calling off a planned civil disobedience at City Hall just days before the vote on the mayor’s inclusionary-zoning plan and then giving the plan its blessing. The deal that RAFA struck added a few useful provisions, but it mostly hinged on a study that de Blasio agreed to conduct with the coalition to investigate ways of achieving greater affordability.

* * *

The fight for affordable housing presents other daunting challenges. As Matthew Lasner, associate professor of urban studies and planning at Hunter College, notes: “The only way to really achieve affordable housing [for] people earning low incomes [or] even moderate incomes in a big, expensive city like New York is through deep subsidies.” And the entity best suited to provide them is the government.

Ironically, public-housing projects, which would create truly affordable housing without the attendant luxury development, remain both the best solution and the one deemed politically impossible. Public housing has never been popular with those in power in this country, and it became even less so after the racialized backlash against civil rights and urban areas that helped dismantle the system. “Since then,” Lasner said, “we’ve been struggling with trying to invent all kinds of ways to work around doing what we really need to do.” Even with de Blasio’s progressive tweaks, inclusionary zoning doesn’t go far enough.

Westin agreed that the housing fight is bigger than inclusionary zoning: “I think it starts with the crash of 2008, and the fact that Wall Street had speculated so much on neighborhoods all over the country.” For him, the question is how to challenge the power of Wall Street and the real-estate industry and use some of their capital to pay for affordable housing—whether through inclusionary zoning, principal reduction on home loans artificially inflated by speculation, or some other means of taking back wealth extracted from poor and working-class communities.

But winning the fight on affordable housing goes beyond deciding on a plan; it also means deciding which tactics will work. Large protests and civil disobedience are a good first step, but can they stop a policy that politicians and developers really want? The answer, with inclusionary zoning, seems to be no. NYCC faced criticism simply for daring to demand more of a progressive mayor—and then for backing the plan once it became inevitable.

It’s also hard to create a national movement that can bring pressure on local officials when the issue is housing rather than wages. As Lasner pointed out, because of its size and density, New York is largely an outlier among US cities, most of which don’t have the same kinds of housing needs. That means New York activists are on their own, up against some of the richest people in the world, who look at their neighborhoods and see dollar signs.

For NYCC, this is where the lessons of the Fight for $15 don’t translate. The workplace, as someone named Marx once noted, is uniquely suited for class struggle: Workers refusing to work can bring the entire enterprise to a halt. One of the challenges for those organizing for affordable housing is to find a similar tactic. Rent strikes have a long history, as does squatting. But what can East New Yorkers do to force anyone to build housing they can afford? As NYCC continues to fight for a city that working-class people of color can live in, it will need new ways to put pressure on officials and developers. (One possible start: a new NYCC campaign, the Real Gentrifiers, which uses tactics similar to those of the Hedge Clippers to bring direct action to the doorsteps of the wealthy developers making money from “affordable housing.”)

The lesson that might apply, from both the Fight for $15 and the Hedge Clippers, is that when you begin to tackle power at its source and make big, ambitious demands, you can shift the debate on a more fundamental level. “Remember that the little people are the backbone to the city,” said Rachel Rivera. “The big people have the money, but they can’t do anything without us.”

Sarah JaffeSarah Jaffe is a reporting fellow at Type Media Center and the author of Necessary Trouble: Americans in Revolt and Work Won’t Love You Back.