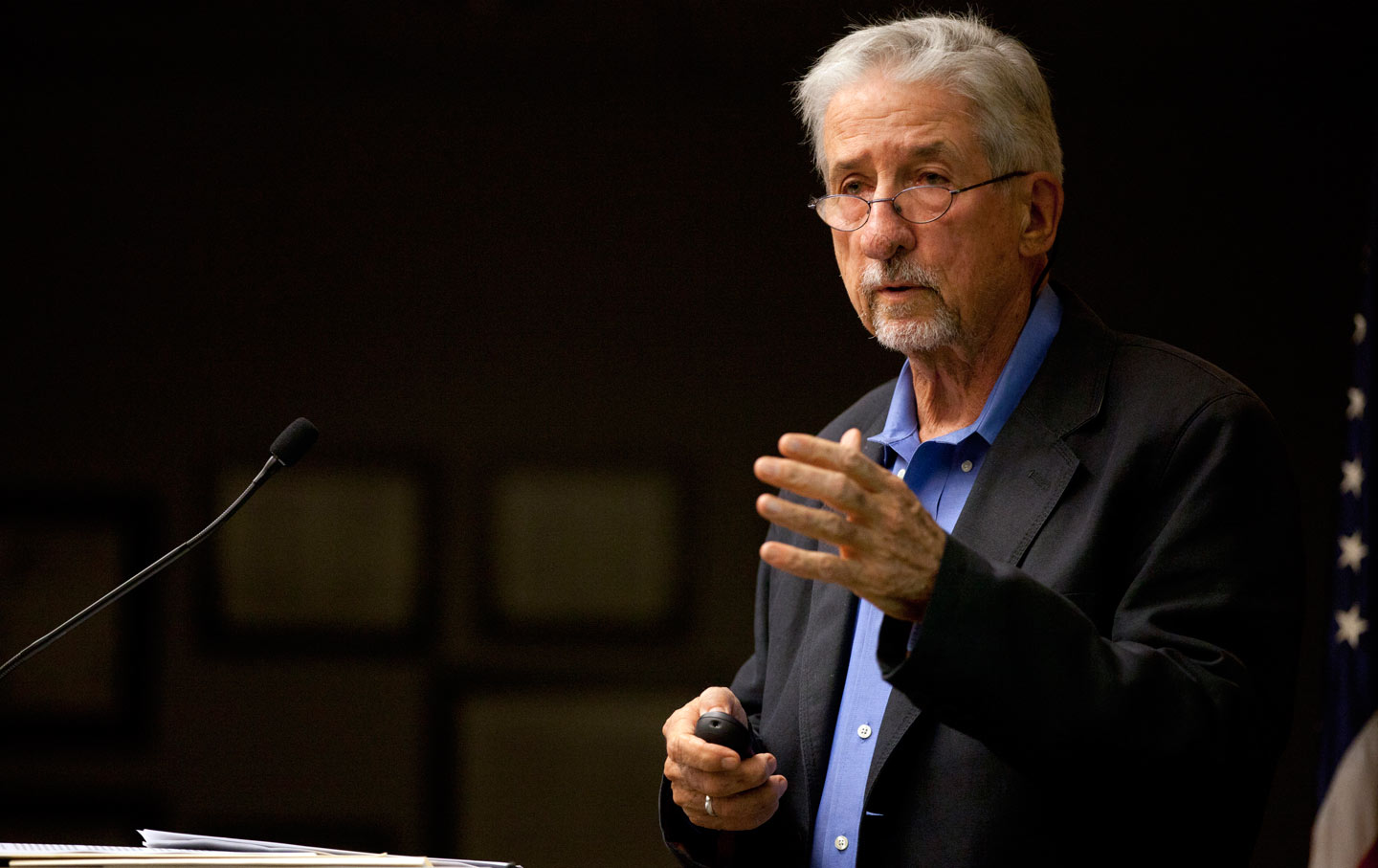

University of Michigan graduate and political activist Tom Hayden speaks about climate change at the Downtown Ann Arbor Library Branch in Ann Arbor, Michigan, on Monday, September 15, 2014.(AP Photo / The Ann Arbor News, Patrick Record)

A true force of history, Tom Hayden was also an important voice at The Nation, where he served on the editorial board and contributed numerous articles and ideas over the years. To commemorate his passing and the major impact he had on his times, The Nation asked friends of Tom to offer personal remembrances of the man and his work. “I never stopped learning from Tom. I’m sure that all of us can say that,” wrote fellow organizer, Mark Rudd. Many others, including Mike Davis, Joan Walsh, Greg Grandin, Phyllis Bennis, Victor Navasky, and Dick Flacks share their fond memories of Tom, and the impact he had on their writing, lives and activism.

Fifty-two years ago this December, an obscure group of young activists, Students for a Democratic Society, held a national council meeting in New York to discuss the next year’s work. As I recall there were about 40 people present, some of them recent veterans of Freedom Summer, others peace and civil rights activists at campuses such as Swarthmore, Michigan, Chicago, Harvard and Tufts.

I was 18, recently expelled from Reed College in Portland, and a coolie in the tiny SDS national office running a mimeograph machine and stuffing envelopes. If it had put to vote, I undoubtedly would have won election from my peers as the most politically naive and painfully inarticulate member of the fledgling New Left.

Although the intricacies of the National Council debate were largely beyond my grasp, the action agenda was breathtakingly audacious. SDS was essentially proposing to declare war on LBJ’s war in Vietnam with a march on Washington the following April, while simultaneously recruiting students into long-term urban organizing projects with the hope of catalyzing an interracial movement of the poor in the North. There was also a proposal to expose Wall Street’s role in financing the apartheid regime in South Africa with a sit-in at the Chase Manhattan Bank.

As NC members drifted into the city for the meeting, I asked one of the veterans—that is to say, a 22-year-old—what to expect. She told me, “Wait till Tom Hayden speaks.” He was already a tribal legend: editor of the Michigan Daily, the principal author of the Port Huron Statement, the victim of a infamous beating in broad daylight in Mississippi, and so on. I expected a brilliant orator, fire coming out of his nostrils.

In the event he was gruff and dog-tired. When he finally spoke, I was embarrassed because I missed the point he was making, if indeed he was even trying to make a point. It was more like a long haiku. I had no idea what to make of him. He was only 26, but struck me as having the manner of a world-weary city-desk editor or father confessor twice his age.

There were many leadership styles to emulate in the movement, but it was the quiet anti-charisma of Bob Moses—the architect of SNCC’s astonishingly courageous Mississippi project—that most influenced SDS in those last days before its uncontrolled explosion into the biggest radical student movement in American history. Tom’s charisma was also anti-charismatic, an unrhetorical gravitas tinctured by Irish melancholy and authenticated by his willingness to repeatedly step into the line of fire.

Although he often shared the stage with clowns and bullshit artists, he was always the most serious person on deck and usually the smartest. He had an acute, almost painful sense of what was at stake in the battles we fought, of the costs to ordinary lives, of the ever present shadow of homegrown fascism. Despite the caricatures that will undoubtedly appear in today’s obituaries, he was a sui generis radical, not a liberal, not a social democrat, not a Marxist.

His celebrity and career in the Legislature once upon a time incited much backbiting and calumny amongst the left. But if anyone has any doubts about the consistent course he steered or his moral toughness and personal courage, they should reflect not just on the Port Huron Statement and the Chicago Seven Trial but the IndoChina Peace Campaign which kept alive the struggle against American genocide when the rest of the antiwar movement had collapsed. His crusade to direct American attention and financial aid to the grassroots participants in the Northern Ireland peace process. His tireless support for the gang truce and a LA peace process when other politicians would not touch the issue.

He was a complex, difficult, impassioned person whom we should honor as one of our great champions of peace and justice. May the circle be unbroken.

My first job involved covering Tom Hayden and his “Campaign for Economic Democracy” at the Santa Barbara News and Review. I had idolized him for his civil rights movement work, maybe even more than his anti-war activism, and I felt blessed to leave college and have this honor; to have his phone number, and his instruction. Tom and CED made me what I am today: A believer that the left can and must work within and take over the Democratic Party to transform our country.

I watched Tom sort of do it, eventually getting elected to the state assembly, then senate from Santa Monica. He compromised, sometimes disturbingly, as on Israel and the death penalty. I witnessed his brilliance, and also his bad behavior, politically, and personally. Eventually, we fell out.

After he left the legislature, he moved to my left. He challenged my support for Hillary in 2008 and my general tolerance for Democratic incrementalism, which I felt I’d partly learned from him. I regret to say I mocked his Obama endorsement for The Nation in 2008; he was not amused.

Then illness, and a determined, awakened sobriety, turned him warm and introspective. We reconnected at The Nation, where this year we both were relatively alone in supporting Hillary Clinton.

He had my back during the primary, but had some helpful feedback, too: He thought my frequent reminders that Bernie Sanders’ supporters were disproportionately white, while true, weren’t helpful, and he told me so in an email:

“Joan, I so respect you, and thank you for your work. I’ve said enough about Bernie supporters being white from white states that I am trying to not put salt in the wound. We very much need his white voters at the end.”

I came back:

“I actually, in my heart, agree with you. But sometimes I let anger and self-righteousness get the better of me.”

And he replied:

“Who doesn’t? I seem to be going through an awakening through AA, overcoming envy and polemics in my life. With my stroke and heart issues, my recovery cannot permit a temper fit.”

I had every intention of going to see Tom after the election but I thought it could wait.

Tom managed to combine a deeply radical analysis with pragmatic and effective action, he was fun to listen and talk to, and he was brave in all that he undertook.

Not everyone knows that Tom played baseball and he played it with skill and craft.

Up until last year, when his medical condition took him off the diamond forever, he was the starting first baseman for the Bay City Monarchs, where he caught countless lousy throws from me at third. Years before, he’d been a batting champ at Dodgertown baseball camp, and he continued to hit the ball well long after he could no longer beat out a throw from the outfield to first base.

On his 70th birthday, we drove to Clover Park field here in Santa Monica. I pitched him 70 fastballs to hit, then he fielded 70 grounders, and we played catch for 70 throws. He played five more seasons with us after that.

He was a beloved youth coach, too. In his hospital room last week a prominent local guy Tom had coached 25 years ago told me that Tom always took the kids’ side against the other coaches and made sure everybody got a fair share of playing time, including the weaker players, and his teams still won.

Tom grew up a Tigers fan, but has worn Dodger blue since he moved to LA in the ’70s. As his body was giving out this past week, he communicated that he wanted to fight to stay alive so he could witness three things. The first was to see the Dodgers in the World Series again after such a long drought. But the night before he died we watched his beloved Dodgers get knocked out of their best World Series shot in decades by the Cubs. By the seventh inning he’d had enough, and signaled to me to turn the game off.

The other two things he said he wanted to live to see were the black community politically mobilized, and Hillary win the election. The last time I saw him alive on the morning before he died, he could no longer speak, but we gave each other the crossed fingers sign.

Today, I celebrate the life of my friend and mentor Tom Hayden. The Port Huron Statement was a light for so many of us, and his leadership in investing ourselves locally was core to my engagement in the radical changes in Santa Monica in the ’70s. His wife, Barbara, loves to sing “Joe Hill,” so today as my heart cries I hear Joe Hill saying, “Don’t mourn, organize.” Tom was working for peace and justice until his last breaths. Be inspired to build your community today. Find two neighbors you haven’t connected with yet, get to know them and discover what values you share.

I last talked to Tom Hayden a week before he died. We’d been calling each other regularly since he’d gotten home after collapsing at the Democratic Convention. In conversation, he expressed merely mild annoyance with his body’s stubborn lack of cooperation, but I could tell his health was getting worse.

I’m thinking of him this morning, because here in Cambridge the big Harvard Dining Hall workers strike—which has gotten a good deal of coverage—is about to end, and I wish he were here to celebrate. Tom and I had strategized at length in our calls about the strike, about messaging, about how best to rally students and faculty, how to maximize press coverage needed to keep pressure on the university’s negotiators. Tom’s interest in the strike was grounded directly in the semester he spent here in 2003 as an Institute of Politics Fellow, an appointment I’d helped arrange.

As a new fellow, Tom had promptly gotten himself in trouble with Harvard by taking a student study group to Miami to observe negotiations of a new hemispheric free-trade pact that was drawing lots of criticism and protest. Four of his students promptly got themselves arrested for marching in a peaceful protest against the pact. Harvard administrators promptly went ballistic, threatening to cancel the entire study-group program. They were furious with Hayden.

He would have none of it. His letter to The Harvard Crimson is worth reading, as an insight into who he still was 40 years after co-founding SDS—and perhaps more important as reminder to the rest of us of the work we’ve left to do.

I remain inordinately grateful to Tom for what I learned from him—most especially that if you’re going to build a powerful movement against a war waged against a nation far away, you have to build into the center of your organizing some understanding of that country, its people, its culture. I learned that lesson first about Vietnam, working with Tom and Jane at the Indochina Peace Campaign for a couple of years right out of college. I worked with others later to build that same understanding into the work we did on Central America, on Iran, on Palestine, and beyond.

There were contradictions. In 1982, Tom was running for California’s State Assembly and Israel occupied Lebanon. At the request of Israeli officials in Los Angeles, Tom and Jane traveled with the invading army, and Tom essentially cheered them on. I refused to talk to him for about 20 years. He resurfaced in DC in 2005 with a powerful strategic plan for the Iraq antiwar movement, and we somehow ended up sitting together (it was Southwest) on a five-hour flight west. Tom spent two hours telling me a spellbinding mea culpa of “how I was bought” by the Israel lobby in Los Angeles when he first ran for state office. And the following year, he published the story as a kind of confession in Bob Scheer’s Truthdig blog. It was an extraordinary recognition of error, apology and recommitment.

Tom also taught us a lot about how to make important connections between issues and movements—his 1972 book on Vietnam, The Love of Possession is a Disease With Them, was taken from a quote from Sitting Bull:

Yet hear me, people, we have now to deal with another race—small and feeble when our fathers first met them but now great and overbearing. Strangely enough they have a mind to till the soil and the love of possession is a disease with them. These people have made many rules that the rich may break but the poor may not. They take their tithes from the poor and weak to support the rich and those who rule. —Sitting Bull, at the Powder River Council, 1877

I remain grateful for all Tom taught me.

I was in a history class a few years back at Columbia University (where I am a much-later-in-life student), when the day’s discussion focused on the Port Huron Statement. The professor asked if anyone knew the name “Tom Hayden,” and a few raised their hands. It was all I could do not to blurt out, “I held a fundraiser for him!”

Which, in fact, I did: When Hayden was running for the US Senate in California. I had met him several times and, like so many others, was intoxicated by his brilliance. No, I am not going to say anything salacious about demons he may have had, or that I may have witnessed. (Though we all knew he was a pretty serious flirt, and hey, he nabbed two beautiful women.) Anyone who was lucky enough to spend time with Tom could not but be impressed by his vast knowledge. And he was never shy about expressing his opinions.

I remember well that event for him: It was on a gorgeous sunny day in Malibu. (What else is new?) I wore blue and Tom gave his pitch in the backyard, with his son, Troy, on his shoulders. Yes, it seems like yesterday. But then whenever someone like Tom passes, we are forced to reassess our own lives and our own levels of activism. His mind excited me enough to take time away from a journalism career to try to convince people that “radical” need not be a nasty word. There were other candidates along the way who sent me on detours, but no one else who put a generation’s angry and righteous thoughts into a powerful statement. Eventually, like John Lewis, Tom decided it was better to get inside to try to make a difference.

I ran into him about a year or so ago at the Brentwood Mart in Los Angeles. We sat for awhile and he, of course, had something to say about what was going on in the state, and the country. He looked his age and seemed rather tired. Hey, no one deserves a good rest more.

I never stopped learning from Tom. I’m sure that all of us can say that.

People should look at his brilliant 2009 book, The Long Sixties. In it he puts forward, in the first five pages of the introduction, a theory of mass movements, how they grow, succeed, and then decline. Then the rest of the book is an explication of the theory based on 50 years experience in the movement. Considering how little we have toward a theory of movement building, Tom’s work is of incalculable value, a true beginning. Might anyone want to look at his theory and comment? Perhaps we could create a separate thread.

As many people have said, Tom was always thinking strategically, He always knew that the goal is power, while so many of us, unlike the right, avoided the problem of power by sticking to single issue campaigns or, much worse, wasting decades on useless dead-ends like Marxist-Leninist party building. I often wonder what might have happened had more New Leftists followed Tom’s lead and entered into the Democratic Party to openly fight for its soul, instead of simply abandoning it to the Clintons and the DLC. Finally, decades later, Bernie’s brought the fight out into the open. But it remains to be seen how many young people will join in by organizing electoral campaigns for school boards, county commissions, city councils, and state legislatures. As Tom did.

We’ll be learning from Tom for years to come.

I was lucky to have gotten to know Tom over the last couple of years, starting around the time, I think, of Dilma Rousseff’s first election as president of Brazil. He wrote to say he was worried that the powers that be wouldn’t allow her to win. I replied that she would, that her Workers Party represented institutional stability and markets like stability. Turns out I was right in the short term (she was elected and took office) and he was right in the long term (Dilma was just ousted from power in an elite-backed “soft coup”). Over the subsequent years, we talked and corresponded. Tom was a stalwart on Central America, not just in the 1980s as the wars raged, but their aftermath, active with refugee communities who had fled into southern California. Tom had a coruscating intellect and a wry sense of humor—the intellect I was awed by, the humor I recognized, as a fellow working-class lapsed Catholic. It could be biting, but in Tom’s case, the bite was softened by his decency and generosity. I didn’t agree with Tom on a number of things, but was always impressed by his dazzling ability to spin out from any given political conjuncture realistic short- and long-term strategies to achieve progress (or so they seemed realistic as he talked). Tom made you believe, despite yourself, that we could, maybe, stop the war or push whatever Democrat who happened to be in office to dismantle the national security state. Let’s hope he is right in the long term.

Every time I reread the Port Huron Statement, I am stunned by the clarity of thought and elevation of rhetoric. When I first read it, as a junior-high-school student in Memphis, I felt it was speaking right to me and for me. And when I taught it to students in London a few years ago, I felt the same way. For me the Port Huron statement is the only American manifesto from my lifetime that can stand beside the great abolitionist broadsides of Douglass or Garrison or the writings of Jefferson and Madison.

As I.F. Stone said about Norman Thomas, Tom Hayden spoke Socialism in a distinctly American vernacular. I just looked up the exact quote, which is, “I admired his [Thomas’s] capacity to deal with American problems in Socialist terms, but in language and specifics that made sense to ordinary Americans.” I know Michael Harrington is widely considered Thomas’s heir, but to me Hayden’s indomitable activism, his willingness to put himself and his beliefs on the line again and again, and above all the rich vein of utopian energy and faith in human improvement that runs through all of his writing are much closer to Thomas. Hayden wasn’t always right; but his willingness to take the risk of commitment, despite the bitter disappointments, seemed to me genuinely heroic. So RIP, Tom Hayden. And good luck organizing the heavenly host.

I first met Tom when he was a community organizer for SDS in Newark in 1964 or ’65. I was a student going to college in New Jersey, and Tom came down to tell our SDS chapter about organizing poor people, and about how and why black Newark was going to explode (and of course it did, in 1967). He was already a hero to us, even before the Vietnam war took over everything on the left. And when the war and “the sixties” came to an end, Tom again led the way by making an unpopular choice on the left: working within the Democratic Party, as an elected state representative in California for 18 years, practicing politics at the far left of the possible.

Tom had a keen sense of history, and he knew that Vietnam was the central historical fact of our generation. One of his last campaigns came in 2015 with the 50th anniversary of the war, when historians and old-time activists feared the worst. The Pentagon commemoration office, which Congress authorized at a cost of up to $65 million, promised a nationwide program around its portrayal of the war as one of “valor” and “honor”—a picture unrecognizable to many Americans, including both veterans and antiwar activists. In response, Tom led a campaign seeking “a full and fair reflection of the issues which divided our country during the war.” It seems now like they have succeeded.

Tom was an amazing person—a visionary strategist and a grassroots activist, a community organizer and an elected official. We won’t have another one like him.

Ever since Port Huron, I’ve felt that Hayden was as much, or even more, a teacher than a leader. Hayden was a man of the left, but he wanted a left that struggled to win. Accordingly, from the time, at age 20, that he committed himself to the left, he wanted to change some fundamental habits of thought and styles of action that he found there.

He was guided by a fairly coherent philosophical pragmatism, learned from his Michigan professors like Arnold Kaufman and Kenneth Boulding, from immersion in the writings of Mills, as well as now neglected heroes of the late 1950s and early ’60s, Albert Camus and Paul Goodman. Our passion and our action, this pragmatism says, should be guided by our experience, rather than ideological doctrine, theory or concealed thirst for power. Here, Hayden teaches, are some tips for activist practice:

The dream of a left rooted in American history and reality and able to speak to and for an American majority is generations old and yet to be realized. Hayden came to see such a left worth dreaming. And his life work helped make it more possible. It’s a life worth studying, not just honoring.

Various Contributors