Tony Benn Taught Us That Every Generation Must Struggle for Radical Democracy

The British parliamentarian, who would be 100 today, challenged militarism, colonialism, neoliberalism, and the complacency of centrists in the face of billionaire-class oligarchy.

Tony Benn addresses a crowd in Parliament Square, London during a demonstration by the Stop the War Coalition on June 15, 2008.

(Epics / Getty Images)Tony Benn, the legendary British parliamentarian whose epic battles against oligarchy made him a hero of the global left, would have turned 100 today. Benn, who died at age 88 in 2014, continues to influence our politics and a new generation of activists because he offered a radical vision of economic and social democracy based on the power of movements to challenge injustice. As he always said, “Two flames have always been burning in the human heart, the flame of anger against injustice and the flame of hope that you can build a better world—and those two flames are really material by which we make progress.”

Hopeful but realistic—anticipating the message of our great contemporary philosopher Rebecca Solnit—Benn would always counsel that making something of those materials would require a multigenerational and unyielding activism rooted in the understanding that “every generation has to do it for themselves again, there is no railway station called justice that if you catch the right train you get there, every generation has to fight for their rights.”

Benn knew the equation because he lived it. Born in London on April 3, 1925, he met Mahatma Gandhi when he was 12. He began his five decades of service in the British Parliament in 1950—when Clement Attlee was prime minister and Winston Churchill the leader of the conservative opposition—and left after Tony Blair became prime minister. In between, he knew and defended Nelson Mandela when the embrace of the anti-apartheid struggle was still seen as a radical act, advocated for Palestinians when they had few allies in the corridors of power, renounced his inherited title as the 2nd Viscount Stansgate so that he could continue to serve in the people’s parliament (declaring, “I am not a reluctant peer but a persistent commoner”), ushered in a new age of popular communications and connectivity as Britain’s pioneering minister of technology in the 1960s and ’70s, championed cooperatives and worker ownership as Britain’s minister of industry in the ’70s, battled not just Margaret Thatcher but the compromising leaders of his own Labour Party on behalf of the working class in the ’80s, and finished his almost 60 years of public life as an international leader of the opposition to the wars of whim and folly that have stolen so much of the promise of our time.

Benn was a proud radical, an anti-colonialist, an enthusiastic socialist, and the inspiration for generations of activists, organizers, parliamentarians, presidents and prime ministers around the world—including Jeremy Corbyn, the former UK Labour Party leader who recalled today that “Tony was driven by the radical idea that all human life had equal value. We all have inspirations—and he was mine.”

Across the quarter-century that I knew him, Benn identified most proudly as a small-“d” democrat, a tireless promoter of a power-to-the-people ethic that placed its faith in the great mass of humanity rather than billionaires, media moguls and political powerbrokers.

The last time that Tony and I appeared together at a public event—a symposium in London put on by Britain’s brilliant Campaign for Press and Broadcast Freedom that recalled his famous declaration that “broadcasting is really too important to be left to the broadcasters”—he reminded me of his belief that those in positions of economic, social, and political power should always be asked five questions:

—“What power have you got?”

— “Where did you get it from?”

— “In whose interests do you use it?”

— “To whom are you accountable?”

— “How do we get rid of you?”

Benn asked these questions everywhere he went. I saw him write them on the chalkboards of classrooms and lecture halls. I heard him repeat them at rallies, protests and marches.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →I think his favorite of the questions—as a political figure who delighted in the give and take of campaigning, the debates, the canvasses, the counts in his initial constituency of Bristol South East and in the historic mining constituency of Chesterfield that he represented in the final decades of his remarkable career—was: “How do we get rid of you?”

“Anyone who cannot answer the last of those questions does not live in a democratic system,” Benn explained.

“Only democracy gives us that right. That is why no one with power likes democracy,” he would continue. “And that is why every generation must struggle to win it and keep it—including you and me, here and now.”

In fairness, it was not quite true that “no one with power likes democracy.” Benn himself was proof of that.

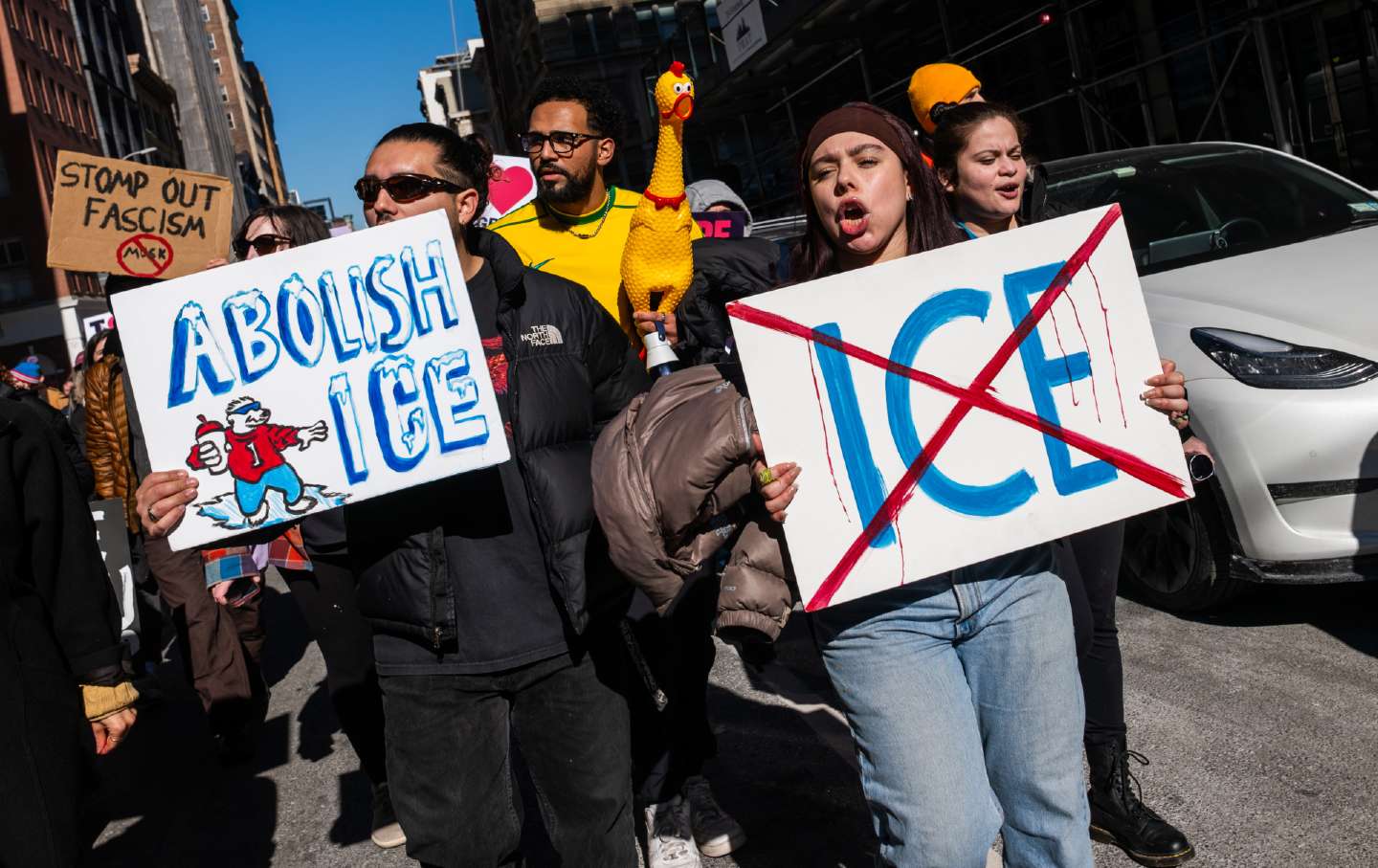

He held power, as a revered parliamentarian, a minister of state, a competitor for the leadership of his party and a figure of international prominence who traveled in the circles of heads of state. Yet he was happiest when he was in the street, marching, speaking truth to power, challenging prime ministers and presidents.

In Tony’s view, citizens could not be spectators—especially in the face of the coalescence of wealth and power that he warned of long before Donald Trump and Elon Musk confirmed the threat that oligarchy posed to democracy.

This is why he championed media and political reform, embracing structural changes that would take power away from unelected billionaires and their political pawns and give it to the people. The great historical struggle, he argued, was always over the scope and character of democracy.

When I was with Tony in Chesterfield and London and too many other locations to count over the decades of our friendship, we often spoke of Tom Paine, the English radical who inspired an American revolution. Tony was passionate about Paine and about all the other dissenters, be they British or American or Indian or South African, suffragists and civil rights marchers, anti-colonialists and anti-apartheid campaigners, who suffered, struggled, and persevered in the cause of democracy.

“A historical perspective is the key to democratic politics, which if denied can bury the real issues and confine news coverage to high-level gossip about the rich and the powerful, reducing us to the role of spectators of our fate, rather than active participants,” he argued. “The obliteration of the past strengthens the short-term calculations that pass for political thought, and for me the real heroes are those few who try to explain the world in order to help us to understand what we can best do to improve our lot.”

Tony Benn explained the world, better than anyone I knew. And he was never, ever willing to accept the role of spectator in the great democratic debate, and the great democratic life, that he sought. On the one-hundredth anniversary of his birth, we honor him best by asking his questions, and by recognizing that every generation must struggle to win democracy—and to keep it.