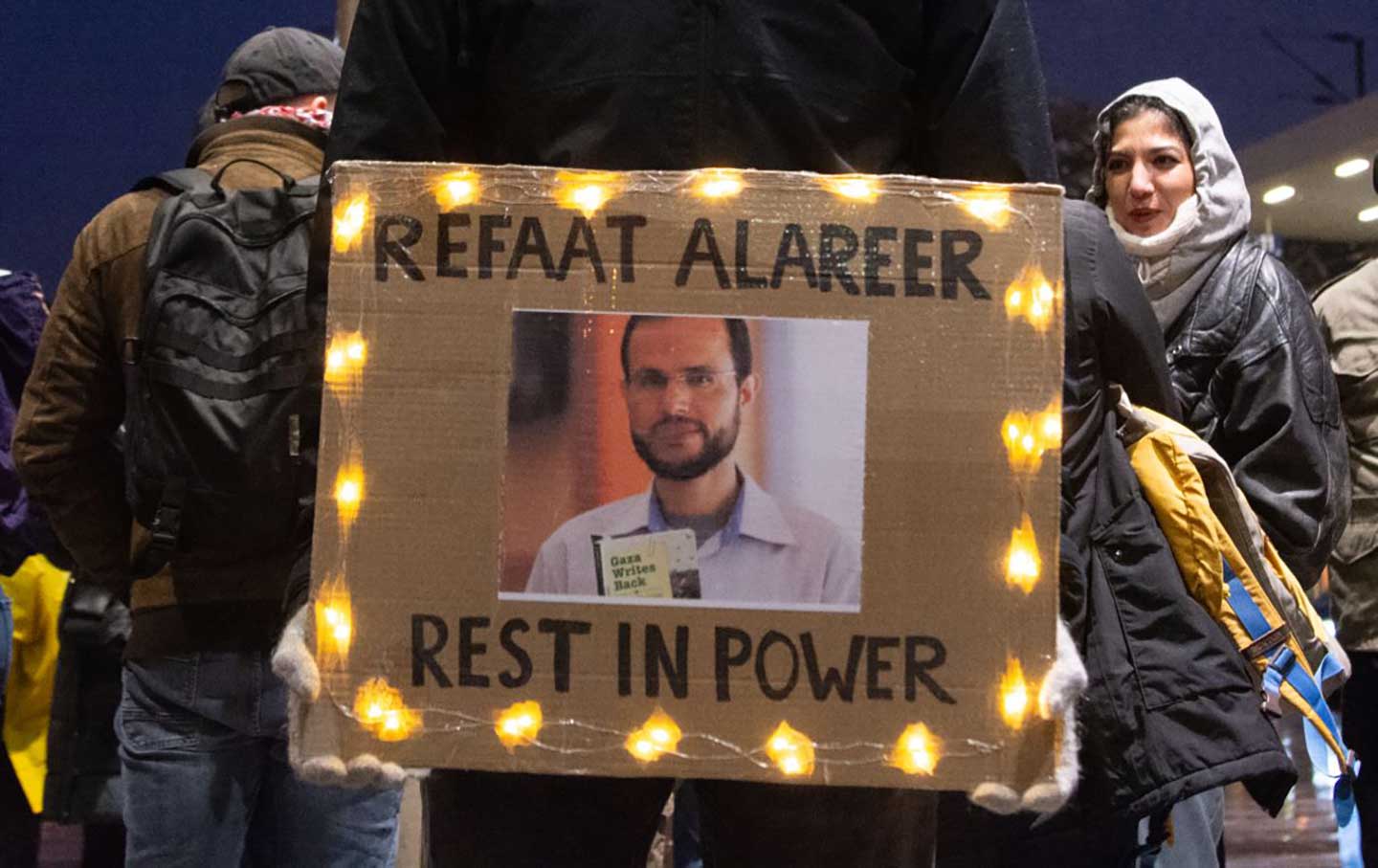

Refaat Alareer Was a Brilliant Poet and Intellectual—He Was Also My Teacher

To those of us lucky enough to learn from him, Alareer offered a chance to explore new worlds and stories, defying the laws of physics and oppression.

On a hectic weekday in 2004, I was unexpectedly called to the principal’s office at my school in Deir el-Balah, a city in the central Gaza Strip. As a 10th grader, I was sure I hadn’t done anything to warrant this unexpected summons. I sat down, surrounded by the principal, his deputy, and members of the teaching staff. After a period of waiting and suspense, the principal informed me that I had been selected to attend a one-year English language ACCESS Microscholarship Program offered by the American educational nonprofit Amideast in Gaza City. I felt a surge of pride, joy, and excitement.

On the course’s first day, I traveled with other students from a meeting point in Deir el-Balah to Gaza City by bus. The commute involved passing through the Israeli “Sea Checkpoint,” then located near the illegal Israeli settlement of Nitzarim, which separated Gaza City from the central and southern parts of the Strip. As I entered the classroom, I was greeted by a young teacher with a light beard and a gentle smile, welcoming every student into his classroom. He introduced himself as Refaat Alareer, whom we affectionately called Mr. Refaat. From the first day, we, his students, realized how fortunate we were to have Mr. Refaat as our teacher. The moment he picked up his Expo marker—a symbol later used to honor his memory—he taught us English as not just a language of vocabulary, grammar, and structures but also a tool for more profound understanding and expression.

On December 7, Refaat was tragically killed in an Israeli air strike that flattened his sister’s apartment, also taking the lives of his brother Salah, Salah’s son, his sister Asmaa, and Asmaa’s three young children. Upon seeing a post on X accounting Refaat’s death, I was engulfed in shock and disbelief. News of his death swiftly spread worldwide. As Yousef Aljamal, one of Refaat’s closest friends put it, he was a universal figure. Refaat yearned to be part of a world that extended far beyond the confines marked by Israel’s walls. In his quest, he forged strong bonds and friendships globally. Those familiar with him, his writings, and his students’ words, as well as those who heard his lectures and interviews, recognized in him a reflection of Gaza’s potential. They were all deeply saddened and devastated by his brutal death.

To understand the impact of Refaat’s loss, it helps to understand a bit about him. As a professor of English literature at the Islamic University in Gaza, Refaat was respected as an intellectual integral to Gaza’s cultural scene, but he was also more than a teacher and professor. For him, the English language was a vehicle for liberation and empowerment. In Gaza, a place beset by decades of occupation, de-development, and isolation, connecting with the outside world was a formidable challenge. Refaat understood that teaching and learning English presented a unique opportunity to break through the physical, intellectual, academic, and cultural barriers imposed by the occupation. He viewed English as an act of resistance and defiance.

Meanwhile, for those of us lucky enough to study under him, being in his classroom transcended the traditional educational experience; he made learning English cool and enjoyable. Refaat did not just impart knowledge; he offered a glimpse of hope, a respite from the relentless pressures of Gaza. His classes were journeys, both intellectual and cultural, beyond the confines of the blockade, allowing us to explore new worlds and stories, defying the laws of physics and oppression.

Refaat taught his students Shakespeare and John Donne, but that was not all. He also introduced his students to Malcolm X, feminist literature, and even the poetry of Yehuda Amichai. This brief exposure allowed us to experience a world far beyond Gaza’s borders, igniting a desire to claim our place in it.

Refaat was born in 1979 in the Shuja’iyya neighborhood, east of Gaza City, where the residents are known for their tenacity, humility, hard work, pride, and dignity. Throughout his childhood and beyond, he grappled with the challenges of living under Israel’s occupation. Even so, despite our nearly two-decade acquaintance and his dedication to empowering others to share their stories, he seldom shared his own.

In 2020, I invited Refaat to contribute to the anthology Light in Gaza: Writings Born of Fire, which explored Gaza’s future in the context of its past and present. I initially suggested he write about the educational sector’s challenges in Gaza. However, after some contemplation, Refaat expressed his desire to share his own story. He titled his chapter, “Gaza Asks: When Shall this Pass?” In it, he detailed how, growing up, people in Gaza would reassure each other with the phrase, “This shall pass” during times of tragedy, loss, or hardship. Refaat, however, witnessing the despair of his brilliant students, friends, and neighbors amid poverty and unemployment, transformed this line of reassurance into a question posed to the outside world.

Refaat saw his contribution to Light in Gaza, as an opportunity to shed light on not just his own plight but that of the 2 million people living and dying under siege; his hope was that it would inspire others to take action. As Gaza’s isolation under the Israeli blockade intensified, he felt a pressing need to bridge the gap in the outside world’s understanding of the pain inflicted on Gazans.

Despite his significant efforts, Refaat knew he was addressing only a fraction of the vast challenges faced in Gaza. Teaching and writing were helpful, but only up to a point. In recent years, as a tenured professor at a university where his position was once considered prestigious, he found himself working two jobs to support his family amid the worsening economic conditions in Gaza.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →This situation left Refaat constantly anxious and worried. In revealing his story in Light in Gaza, he acknowledged that while storytelling is crucial, it requires an audience that is willing to listen, absorb, and act. His and his students’ narratives were not mere artistic expressions but heartfelt pleas for empathy and action to alleviate the suffering in Gaza.

Refaat ended his chapter in Light in Gaza by writing:

When I was approached to write for this book, the promise was that it will effect change and that policies, especially in the United States, will be improved. But, honestly, will they? Does a single Palestinian life matter? Does it? Reader, as you peruse these chapters, what can or will you do, knowing that what you do can save lives and can change the course of history? Reader, will you make this matter? Gaza is not and should not be a priority only when Israel is shedding Palestinian blood en masse. Gaza, as the epitome of the Palestinian Nakba, is suffocating and being butchered right in front of our eyes and often live on TV or on social media. It shall pass, I keep hoping. It shall pass, I keep saying. Sometimes I mean it. Sometimes I don’t. And as Gaza keeps gasping for life, we struggle for it to pass, we have no choice but to fight back and to tell her stories. For Palestine.

Today, in Gaza, the very fabric of Palestinian society is under assault. So, too, is Gaza’s intellectual community—educators, authors, doctors, and poets like Refaat. It’s a cruel and deliberate attempt to extinguish the flame of hope to eradicate the guiding lights of Gaza. Yet Israel overlooks a fundamental truth: With each fallen intellectual, with each destroyed center of learning, a new generation rises, inspired and more determined. They carry forward the legacy of their predecessors, fueled by a shared vision of freedom and liberation. Echoing the title of Refaat’s book, Gaza Writes Back, we will continue to write back. We, his students and those who hold his words and memory dear, will persist in narrating his stories and ours. We will keep telling these tales until we claim our rightful place in the world, until we are free.

Disobey authoritarians, support The Nation

Over the past year you’ve read Nation writers like Elie Mystal, Kaveh Akbar, John Nichols, Joan Walsh, Bryce Covert, Dave Zirin, Jeet Heer, Michael T. Klare, Katha Pollitt, Amy Littlefield, Gregg Gonsalves, and Sasha Abramsky take on the Trump family’s corruption, set the record straight about Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s catastrophic Make America Healthy Again movement, survey the fallout and human cost of the DOGE wrecking ball, anticipate the Supreme Court’s dangerous antidemocratic rulings, and amplify successful tactics of resistance on the streets and in Congress.

We publish these stories because when members of our communities are being abducted, household debt is climbing, and AI data centers are causing water and electricity shortages, we have a duty as journalists to do all we can to inform the public.

In 2026, our aim is to do more than ever before—but we need your support to make that happen.

Through December 31, a generous donor will match all donations up to $75,000. That means that your contribution will be doubled, dollar for dollar. If we hit the full match, we’ll be starting 2026 with $150,000 to invest in the stories that impact real people’s lives—the kinds of stories that billionaire-owned, corporate-backed outlets aren’t covering.

With your support, our team will publish major stories that the president and his allies won’t want you to read. We’ll cover the emerging military-tech industrial complex and matters of war, peace, and surveillance, as well as the affordability crisis, hunger, housing, healthcare, the environment, attacks on reproductive rights, and much more. At the same time, we’ll imagine alternatives to Trumpian rule and uplift efforts to create a better world, here and now.

While your gift has twice the impact, I’m asking you to support The Nation with a donation today. You’ll empower the journalists, editors, and fact-checkers best equipped to hold this authoritarian administration to account.

I hope you won’t miss this moment—donate to The Nation today.

Onward,

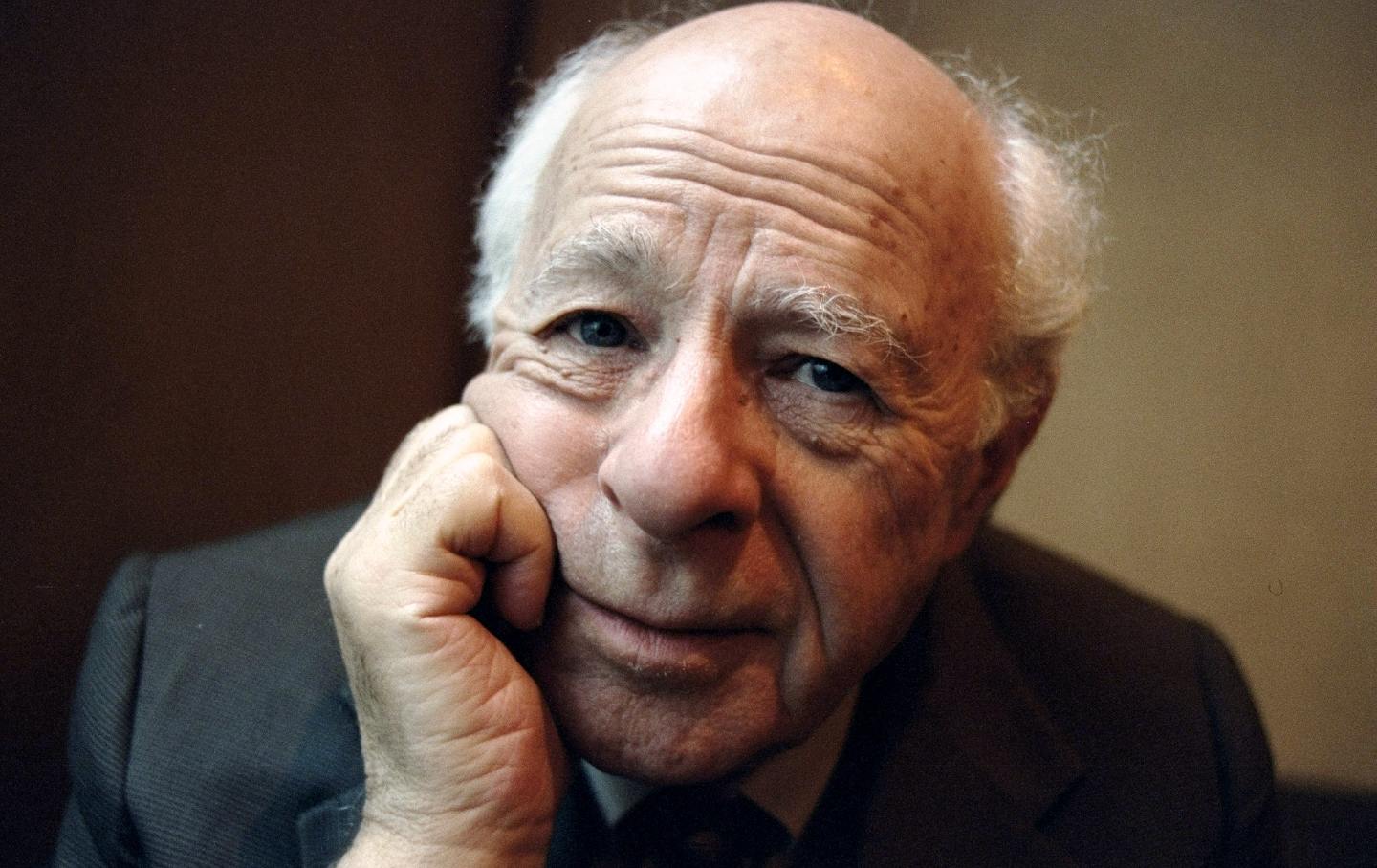

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editor and publisher, The Nation