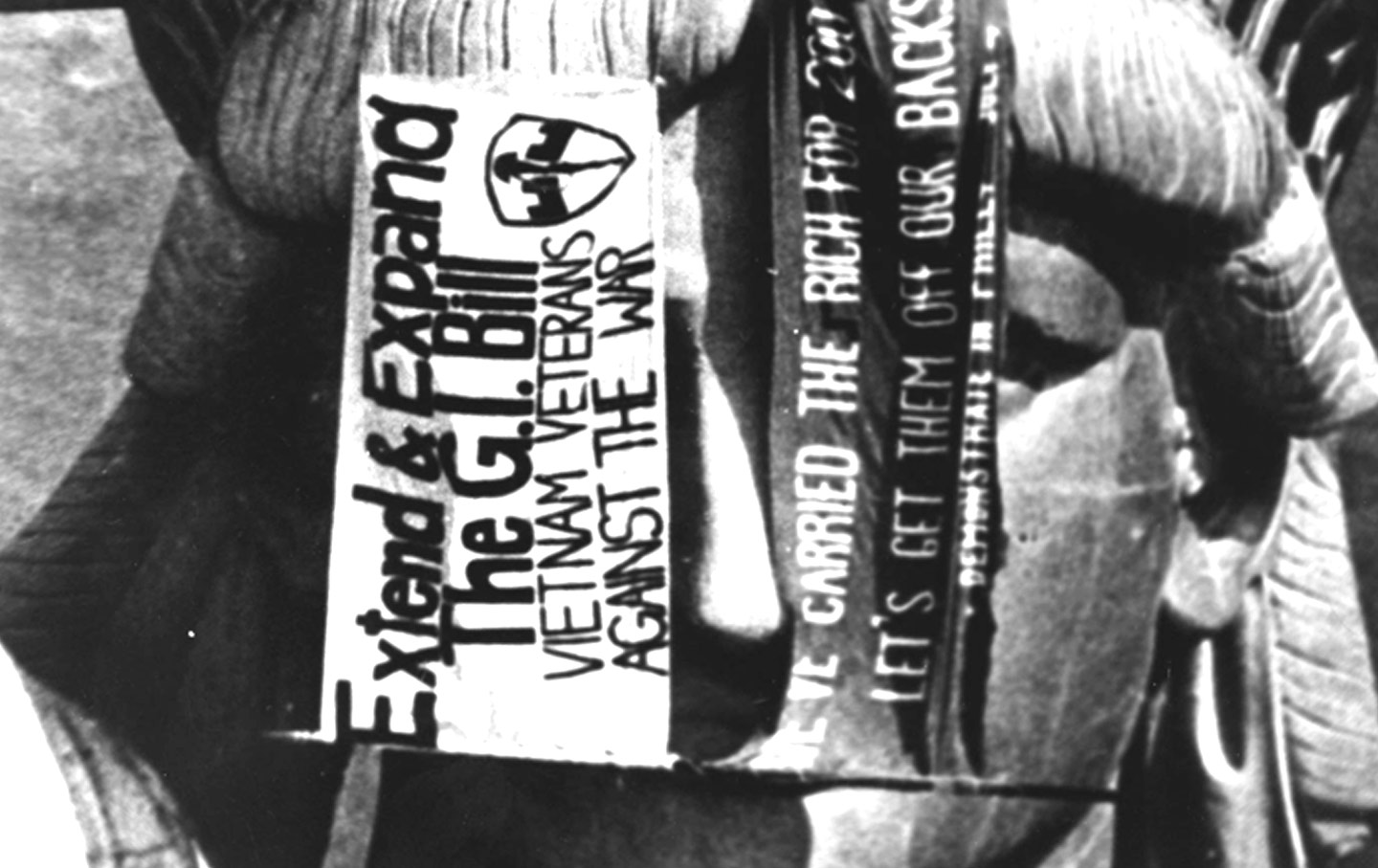

Vietnam Veterans Against the War occupied the Statue of Liberty twice: once in 1971 to oppose the war, and again in 1976 (shown here) to bring attention to veterans’ causes. (Courtesy of VVAW Inc)

When the Pentagon announced its plans for the nation’s official commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the Vietnam War, historians and old-time activists feared the worst. The Pentagon commemoration office, which Congress authorized at a cost of up to $65 million, put up a website in which the war was portrayed as one of “valor” and “honor”—a picture unrecognizable to many Americans, including both veterans and antiwar activists. The general in charge, Claude Kicklighter, promised that the official commemoration would include “educational materials, a Pentagon exhibit, traveling exhibits, symposiums, oral history projects, and much more.” In response, Tom Hayden and a new group, the Vietnam Peace Commemoration Committee, launched a petition last September declaring that “this official program should include viewpoints, speakers, and educational materials that represent a full and fair reflection of the issues which divided our country during the war.” Almost 1,500 people signed, including many prominent historians. (I was one of them.)

Now the Pentagon has abandoned its plans to develop educational and classroom materials. After meeting with Hayden and five other leaders of the committee in January, a Pentagon official declared in a March 19 e-mail that the Defense Department was shifting its mission from “education and history” to the much more limited one of thanking and honoring Vietnam veterans “for their service and sacrifice.” The official also pledged that the much-criticized “Interactive Timeline” on the Pentagon’s website would be replaced, and asked the Vietnam Peace Commemoration Committee to suggest historians who could help with an independent review of the revised version.

The problems with the timeline had been featured in a page-one story in The New York Times, which described the challenge being organized by Hayden and the peace commemoration committee and the criticisms of the Pentagon project from “leading Vietnam historians.” The timeline featured Medal of Honor winners but didn’t mention the 1971 Senate committee testimony of John Kerry, then a leader of Vietnam Veterans Against the War, who posed one of the most devastating questions of the era: “How do you ask a man to be the last man to die for a mistake?” The Times noted that the timeline gave “scant attention” to “the years of violent protests and anguished debate at home.”

And there were the other issues. Historian Stanley Kutler—who died on April 7, and who is best known for suing to get the Nixon White House tapes released—asked last November in The Capital Times of Madison, Wisconsin: “Will the Pentagon acknowledge the mistakes of American presidents and generals who for seven years steadily increased our commitment to more than 500,000 troops, the largest army raised since World War II? Will it recognize the growing public protests against the war, with increasing criticism in Congress, until eventually it was willing to cut off funding for the war, an unprecedented step which pointedly rejected the validity of the war?” And finally, “What will the Pentagon say to Vietnam veterans who actively criticized, questioned, and opposed the war, then and now?” One more problem: The website’s fact sheet listed the total American deaths, 58,253—but it didn’t mention the number of Vietnamese, Laotians, and Cambodians killed, commonly estimated at 3 million to 4 million.

The Pentagon’s change of plans is “good,” Hayden told me. “The threat of a false narrative will always be there, but we don’t need to fight an overpowering antagonist on the battlefield of memory if we can help it. If they focus on honoring vets, that would allow us to preserve and develop the legacy of the peace movement and the lessons for today.”

* * *

As we go to press, the old Pentagon timeline is still in place on the official website—although the entry for My Lai was changed after award-winning journalist and Vietnam War historian Nick Turse, writing at TomDispatch.com, pointed out that, among other things, the site had grossly understated civilian deaths. But the Pentagon still doesn’t call My Lai a “massacre”; instead, the timeline reads: “Americal Division Kills Hundreds of Vietnamese Civilians.” (Emphasis added.) The other materials that the Pentagon has released, however, are much more modest and limited than the department’s original announcement suggested. The official 30-minute commemoration video, Veterans of Valor, opens with President Obama addressing a group of vets assembled at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial on Memorial Day in 2012: “You came home and were sometimes denigrated when you should have been celebrated.” The country needs to tell vets that “you served with honor; you made us proud,” Obama adds. Of course, a lot of people—and a lot of vets—are not proud of what Americans did in Vietnam.

The official video focuses on the daily experiences of the troops and features nine vets. They talk about their first day in Vietnam (one remembers that it was “very traumatic”; when he got off the plane, he saw “rows of coffins with American flags” about to be sent back to the United States). They describe their food and equipment, the mailbag, and the jungle where “snakes had the right of way.” They talk about the terrors of combat, and also of seeing Bob Hope and listening to their favorite songs: One says his was the Animals’ “We Gotta Get Out of This Place”; a black vet lists James Brown’s “Say It Loud—I’m Black and I’m Proud”; and another cites what he remembers as “I Don’t Get Any Satisfaction”—“We played that frequently,” he says.

In the official video, only one vet refers to opponents of the war. The narrator says, “You can protest the war and disagree with the war, but the soldiers are doing what the nation asked them to do.” True enough. However, the video at that point shows demonstrators carrying a huge banner that says support our troops—bring them home. The video ends with then–Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel, another famous veteran of the war, calling the vets “quiet heroes” who were “humble, patriotic, and selfless”—which you’d have to call empty rhetoric. After that, a series of younger GIs and veterans say things like “My generation thanks you” and “Your sacrifices were not in vain”—which most vets know isn’t true, since we lost the war. It turns out that all nine of the vets featured in the official video now work for the Army as civilians in the logistics office, which is headquartered at the Pentagon. Maybe that explains what’s missing: stories about taking drugs, handling Agent Orange, or killing Vietnamese civilians, and also anything about active-duty GIs opposing the war.

But something else is missing as well. The commemorative video contains nothing about the official purpose of the war, no mention of the argument that it was a “noble” cause (Ronald Reagan’s word), a war to defend a democracy threatened by communist invasion. Apparently even the Pentagon doesn’t think that would fly today. Most startling of all, since the official video was posted on YouTube in November 2013, it has had a grand total of 227 views—and only ten downloads from the Defense Department site. The official Pentagon commemoration doesn’t seem so massive or relentless after all.

The Pentagon says it has almost 8,000 “partners” organizing commemorative events. That seems huge. I found that my own school, the University of California, Irvine, is listed as a “Commemorative Partner,” but when I asked people at the campus media-relations office about it, they’d never heard of the program and had no idea what was being planned. After some digging, they found we had been signed up by the campus Veteran Services coordinator, Adelí Durón. When I asked her what our campus commemorative events would be, she explained in an e-mail: “We just have to do 2 programs a year during the 2 year commemoration…. It can be programs I’m already doing, they don’t have funding for us, so no pressure to do anything new…. Nothing specific is planned at the moment.” You have to wonder how many other partners have similar “plans.”

On the other hand, many of the commemoration partners are Veterans of Foreign Wars posts and military bases, and some of those have scheduled big events. In North Carolina, for example, Marine Corps Base Camp Lejeune and the local chapter of Vietnam Veterans of America are organizing a four-day event (April 23–26) for what they call a “celebration” of the 50th anniversary of the beginning of the Vietnam War—which doesn’t really seem like something to celebrate. The theme of the event is not that the nation abandoned Vietnam vets; instead, there’s the revealing motto “Never again shall one generation of veterans abandon another.” The event, which will honor “all veterans, all wars,” includes a concert in the park and a breakfast aboard the USS North Carolina battleship memorial. There is space for 550 people.

* * *

Historians and activists have insisted that the Pentagon’s timeline must be accurate, and that the antiwar movement—including Vietnam Veterans Against the War and the big protests—belongs on it. But as Margery Tabankin of the Vietnam Peace Commemoration Committee told me, “They will never be able to adequately explain the peace movement. That really is our job. And it’s important for us to think about what the lessons were and convey them to younger activists today.” (Tabankin went to Hanoi in 1972 as president of the National Student Association, after the group’s CIA funding ended; she was head of Vista under Jimmy Carter and today gives advice on strategic planning and philanthropic and political giving in Los Angeles.)

That job—explaining the peace movement—starts the weekend of May 1–2 in Washington, DC, with two conferences, almost exactly 50 years after the first national march on Washington to protest the war (which took place on April 17, 1965, and was organized by Students for a Democratic Society). First comes an academic conference, where scholars will focus on current historical debates; next comes a public conference that promises to “tell the truth about the war, the role of the antiwar movement in ending it, the war’s lessons for today, and the war’s consequences for the Vietnamese…as well as many American veterans.”

The academic conference, “The Vietnam War Then and Now: Assessing the Critical Lessons,” will run from April 29 to May 1. Organized by New York University and the University of Notre Dame, the conference will be held at NYU’s Washington, DC, center and takes as its motto a statement by Chuck Hagel in his 2014 Veterans Day remarks at the Vietnam Memorial: “The Wall reminds us to be honest in our telling of history. There is nothing to be gained by glossing over the darker portions of a war…that bitterly divided America. We must openly acknowledge past mistakes, and we must learn from past mistakes, because that is how we avoid repeating past mistakes.” The conference will feature debates on the nature of the war (was it a nationalist revolution, a civil war, or an invasion?); whether the United States ever could have won it; whether an end could have been negotiated sooner; and the lessons for foreign policy today. It will end with a round table on “the impacts of the antiwar movement.”

The public conference, “Vietnam: The Power of Protest,” organized by the Vietnam Peace Commemoration Committee, begins on May 1 with a session called “Honoring Our Elders,” featuring Daniel Ellsberg, Staughton Lynd, Marcus Raskin, Cora Weiss, and others. The second day of discussions will start with “What We Did, Why, and Who We Were,” featuring Tom Hayden, Pat Schroeder, and Ron Dellums. The speakers will address “the most common military argument you hear today,” Hayden said, “which is that the war was lost because of the domestic radicals and peaceniks and McGovern. It’s impossible for them to believe a war could be lost without a stab in the back from the home front. This has been a toxic element in American politics since the communist revolution in China in 1949 and the debate over ‘Who lost China?’” Some argue that changed in 1967, when the CIA told President Lyndon Johnson that the peace movement was not communist-controlled. But “many still see the left acting as a covert arm of a foreign power,” Hayden said. “It’s a convenient excuse”—a way of avoiding the fact that most Vietnamese saw the United States as an invading foreign power not too different from France before it.

Other discussions at the public conference will include “The Personal Impact of Our Actions,” featuring Kent State shooting survivor Alan Canfora, draft resister David Harris, and Weather Underground leader Mark Rudd, and “What We Got Wrong, What We Got Right,” a session on the media featuring Frances FitzGerald, author of Fire in the Lake, the unforgettable, bestselling history of the war, among others. The day will end with music by Holly Near and a commemorative walk to the Mall, the Martin Luther King Memorial, the Vietnam Women’s Memorial, and the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, led by members of Congress, clergy, and veterans, and followed by comments from the Rev. George Regas and Julian Bond. The event will also include workshops, songs, poetry, and artwork. If the conference is a success, the organizers say, it will bring together antiwar activists from the 1960s with “young justice fighters” to “deepen the links for the challenges we face today.”

While the Pentagon has abandoned its plans to develop “educational” materials for schools and the public, that task lies at the heart of the work by the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund, the group that built “the Wall,” the famed Vietnam War memorial. Way back in 2003, Congress authorized the fund to build an educational center on the Mall adjacent to it. This is a huge project: 35,000 square feet, two stories underground, with a price tag of $115 million. It was originally scheduled to open in 2014, but the new target is 2019. The educational center will include exhibits on the history of the era. The Vietnam Peace Commemoration Committee’s leaders also met with people at the memorial fund, who told them the historical exhibits will be “inclusive of different perspectives.” How inclusive remains to be seen, of course, and to that end, the two groups will continue to meet.

“This will be a hugely important institution,” Hayden said, “and a huge opportunity for us to gain recognition of the peace movement and our understanding of Vietnam, in a place that millions of people will eventually see.”

* * *

So the official Pentagon commemoration has been scaled back to the rather modest goal of “honoring and thanking” the veterans for their service. What could be wrong with that? Actually, quite a bit. Several have criticized the motives of those whom historian Adam Hochschild calls “the thankers.” Professor Christian Appy of the University of Massachusetts, author of the new book American Reckoning: The Vietnam War and Our National Identity, points out that “‘Thank you for your service’ requires nothing of us, while ‘Please tell me about your service’ might—though we could then be in for a disturbing few hours.” Writing at TomDispatch.com, Rory Fanning, an Army Ranger in Afghanistan who became a conscientious objector, notes: “Thank yous to heroes discourage dissent, which is one reason military bureaucrats feed off the term.” And at Salon, novelist Cara Hoffman notes: “If you are a hero, part of your character is stoic sacrifice, silence. This makes it difficult for others to see you as flawed, human, vulnerable or exploited.”

This year’s anniversary events are hardly the beginning; in previous years, there’s been a whole lot of thanking going on. Last year on Veterans Day, for example, we had a “Concert for Valor” on the Mall, headlined by Bruce Springsteen, Eminem, Rihanna, and Metallica, with special guests Meryl Streep, Tom Hanks, and Steven Spielberg. Starbucks, HBO, and JPMorgan Chase paid for it. The purpose: to say “thank you” to the vets. And the Pentagon project still has 10 years to go: The official commemoration will conclude in 2025, the 50th anniversary of the end of the war, when the South Vietnamese government surrendered and the last Americans departed Saigon in that helicopter on the roof. The organizers of the peace commemoration also hope to conclude that year, with a celebration of the war’s end.

A modest proposal: This year, on the 50th anniversary of the beginning of the war, instead of saying “thank you” to the vets, we should say “we’re sorry.” We’re sorry you were sent to fight in an unjust and futile war; we’re sorry you were lied to; we’re sorry you lost comrades, and years of your own lives, and that you suffered the aftereffects for many more years; we’re sorry the VA has done such a terrible job of taking care of you. On the other hand, we might say “thank you” to the people who worked to end the war—and ask them to tell us about their experiences. We will start May 1–2 in Washington.

Jon WienerTwitterJon Wiener is a contributing editor of The Nation and co-author (with Mike Davis) of Set the Night on Fire: L.A. in the Sixties.