Americans were furious at the inequalities of their country 200 years ago. Could they get as angry today?

Steve Fraser

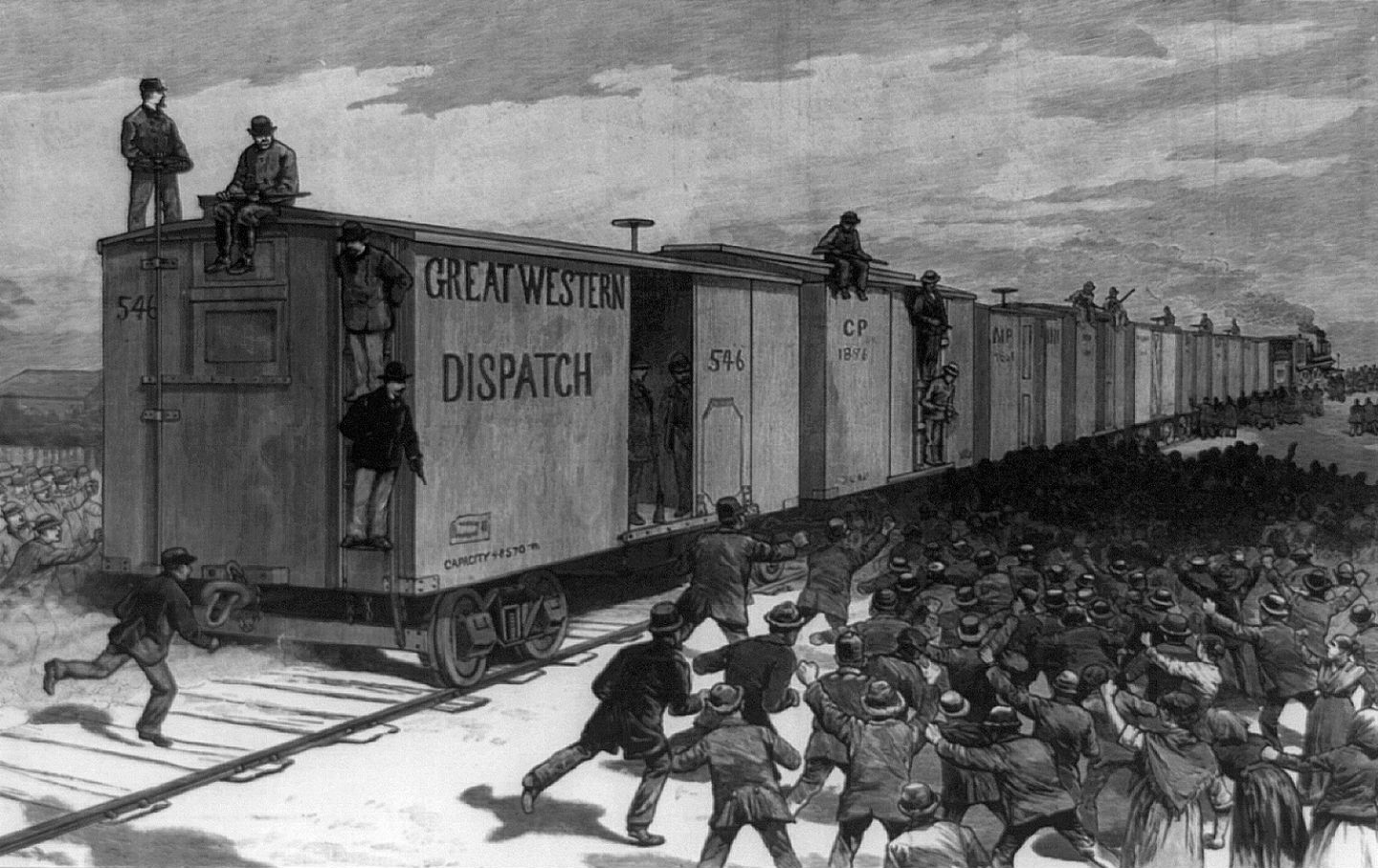

US marshals try to start a train in St. Louis during the Great Railway Strike of 1886. (G.J. Nebinger, Library of Congress)

This article originally appeared at TomDispatch.com. To stay on top of important articles like these, sign up to receive the latest updates from TomDispatch.com.

The following passages are excerpted and slightly adapted from The Age of Acquiescence: The Life and Death of American Resistance to Organized Wealth and Power (Little, Brown and Company).

Part 1: The Great Upheaval

What came to be known as the Great Upheaval, the movement for the eight-hour day, elicited what one historian has called “a strange enthusiasm.” The normal trade union strike is a finite event joining two parties contesting over limited, if sometimes intractable, issues. The mass strike in 1886 or before that in 1877—all the many localized mass strikes that erupted in towns and small industrial cities after the Civil War and into the new century—was open-ended and ecumenical in reach.

So, for example, in Baltimore when the skilled and better-paid railroad brakemen on the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad first struck in 1877 so, too, did less well off “box-makers, sawyers, and can-makers, engaged in the shops and factories of that city, [who] abandoned their places and swarmed into the streets.” This in turn “stimulated the railroad men to commit bolder acts.” When the governor of West Virginia sent out the Berkeley Light Guard and Infantry to confront the strikers at Martinsburg at the request of the railroad’s vice president, the militia retreated and “the citizens of the town, the disbanded militia, and the rural population of the surrounding country fraternized,” encouraging the strikers.

The centrifugal dynamic of the mass strike was characteristic of this extraordinary phenomenon. By the third day in Martinsburg the strikers had been “reinforced during the night at all points by accessions of working men engaged in other avocations than railroading,” which, by the way, made it virtually impossible for federal troops by then on the scene to recruit scabs to run the trains.

By the fourth day, “mechanics, artisans, and laborers in every department of human industry began to show symptoms of restlessness and discontent.” Seeping deeper and deeper into the subsoil of proletarian life, down below the “respectable” working class of miners and mechanics and canal boat-men, frightened observers reported a “mighty current of passion and hate” sweeping up a “vast swarm of vicious idlers, vagrants, and tramps.” And so it went.

Smaller cities and towns like Martinsburg were often more likely than the biggest urban centers to experience this sweeping sense of social solidarity. (What today we might call a massing of the 99%.) During the 1877 Great Uprising, the social transmission of the mass strike moved first along the great trunk lines of the struck railroads, but quickly flowed into the small villages and towns along dozens of tributary lines and into local factories, workshops, and coal mines as squads of strikers moved from settlement to settlement mobilizing the populace.

In these locales, face-to-face relations still prevailed. It was by no means taken for granted that antagonism between labor and capital was fated to be the way of the world. Aversion to the new industrial order and a “democratic feeling” brought workers, storekeepers, lawyers, and businessmen of all sorts together, appalled by the behavior of large industrialists who often enough didn’t live in those communities and so were the more easily seen as alien beings.

It was not uncommon for local officials, like the mayor of Cumberland, Maryland, to take the side of the mass strikers. The federal postmaster in Indianapolis wired Washington, “Our mayor is too weak, and our Governor will do nothing. He is believed to sympathize with the strikers.” In Fort Wayne, like many other towns its size, the police and militia simply could not be counted on to put down the insurrectionists. In this world, corporate property was not accorded the same sanctified status still deferred to when it came to personal property. Sometimes company assets were burned to the ground or disabled; at other times they were seized, but not damaged.

Metropolises also witnessed their own less frequent social earthquakes. Anonymous relations were more common there, the gulf separating social classes was much wider, and the largest employers could count on the new managerial and professional middle classes for support and a political establishment they could more often rely on.

Still, the big city hardly constituted a DMZ. During the mass strike of 1877 in Pittsburgh, when 16 citizens were killed, the city erupted and “the whole population seemed to have joined the rioters.”

“Strange to say,” noted one journalist, elements of the population who had a “reputation for being respectable people—tradesmen, householders, well-to-do mechanics and such—openly mingled with the [turbulent mob] and encouraged them to commit further deeds of violence.” Here, too, as in smaller locales, enraged as they clearly were, mass strikers still drew a distinction between railroad property and the private property of individuals, which they scrupulously avoided attacking. Often enough the momentum of the mass strike was enough to win concessions on wages, hours, or on other conditions of work—although they might be provisional, not inscribed in contracts, and subject to being violated or ignored when law and order was restored.

“Eight Hours for What We Will”

Brickyard and packinghouse workers, dry goods clerks, and iron molders, unskilled Jewish female shoe sewers and skilled telegraphers, German craftsmen from the bookbinding trade and unlettered Bohemian freight handlers, all assembled together under the banner of the Knights of Labor or less formal, impromptu assemblies. The full name of the Knights was actually the Noble and Holy Order of the Knights of Labor, a peculiar name that like so much of the electric language of the long nineteenth century sounds so dissonant and oddly exotic to modern ears. With one foot in the handicraft past and the other trying to step beyond the proletarian servitude waiting ominously off in the future, the Knights was itself the main organizational expression of the mass strike. It was part trade union, part guild, part political protest, part an aspiring alternate cooperative economy.

At all times and especially in smaller industrial towns, the Knights relied on ties to the larger community—kin, neighbors, local tradespeople—not merely the fellowship of the workplace. Like the Populist movement, it practically constituted an alternative social universe of reading rooms, newspapers, lecture societies, libraries, clubs, and producer cooperatives. Infused with a sense of the heroic and the “secular sacred,” the Knights envisioned themselves as if on a mission, appealing to the broad middling ranks of local communities to rescue the nation and preserve its heritage of republicanism and the dignity of productive labor.

This “Holy Order,” ambiguous and ambivalent in ultimate purpose, nevertheless mustered a profound resistance to the whole way of life represented by industrial capitalism even while wrestling with ways of surviving within it. So it offered everyday remedies—abolishing child and convict labor, establishing an income tax and public ownership of land for settlement not speculation, among others. Above all, however, it conveyed a yearning for an alternative, a “cooperative commonwealth” in place of the Hobbesian nightmare that Progress had become.

Transgressive by its nature, this “strange enthusiasm” shattered and then recombined dozens of more parochial attachments. The intense heat of the mass strike fused these shards into something more daring and generous-minded. Everything about it was unscripted. The mass strike had a rhythm all its own, syncopated and unpredictable as it spread like an epidemic from worksite to marketplace to slum. It had no command central, unlike a conventional strike, but neither was it some mysterious instance of spontaneous combustion. Rather, it had dozens of choreographers who directed local uprisings that nevertheless remained elastic enough to cohere with one another while remaining distinct. Its program defied easy codification. At one moment and place it was about free speech, at another about a foreman’s chronic abuse, here about the presence of scabs and armed thugs, there about a wage cut.

It ranged effortlessly from something as prosaic as a change in the piece rate to something as portentous as the nationalization of the country’s transportation and communication infrastructure, but at its core stood the demand for the eight-hour day. Blunt yet profound, it defined for that historical moment both the irreducible minimum of a just and humane civilization and what the prevailing order of things seemingly could not, or would not, grant. The “Eight Hour Day Song,” which became the movement’s anthem, captured that intermixing of the quotidian and the transcendent:

“We want to feel the sunshine We want to smell the flowers; We’re sure God has willed it.

And we mean to have eight hours. We’re summoning our forces from shipyard, shop, and mill;

Eight hours for work, eight hours for rest Eight hours for what we will.”

When half a million workers struck on May 1, 1886—the original “May Day,” still celebrated most places in the world except in the United States where it began—the strikers called it Emancipation Day. How archaic that sounds. Such hortatory rhetoric has gone out of fashion. The eight-hour-day movement of 1886 and the mass strikes that preceded, accompanied, and followed it were a freedom movement in the land of the free directed against a form of slavery no one would recognize or credit today.

Part 2: A Potemkin Village of the Nouveau Riche

Feudalism of a distinctly theatrical kind was the utopian refuge of the upper classes. Mostly that consisted of a retreat from an active engagement with the tumult around them. Some plutocrats, like George Pullman or J.P. Morgan, were, on the contrary, deeply implicated in running things. Morgan functioned as the nation’s unofficial central banker, but from a distinctly feudal point of view, famously declaring, “I owe the public nothing.”

Other corporate chieftains, like Mark Hanna, a kingmaker within the Republican Party, or August Belmont, who performed a similar role for the Democrats, became increasingly involved in political affairs. (Hanna once mordantly remarked, “There are only two things that are important in politics. The first is money and I can’t remember what the second one is.”) The two party machines had exercised some independence immediately after the Civil War, demanding tribute from the business classes. As the century ran down, however, they were domesticated, becoming water carriers for those they had once tithed. Legislative bodies during this era, including the Senate, otherwise known as “the Millionaires Club,” filled up with the factotums of corporate America.

Far larger numbers of the nouveau riche, a rentier class of landlords and coupon clippers, however, were gun-shy about embroiling themselves. Instead, they confected a hermetically sealed-off Potemkin village in which they pretended they were aristocrats with all the entitlements and deference and legitimacy that comes with that station.

Looking back a century and more, all that dressing up—the masquerade balls where the Social Register elite (the “Patriarchs” of the 1870s, the “400” by the 1890s) paraded about as Henry VIII and Marie Antoinette, the liveried servants, the castles disassembled in France or Italy or England and shipped stone by stone to be reassembled on Fifth Avenue, the fake genealogies and coats of arms, hunting to hounds and polo playing, raising pedigreed livestock for decorative purposes, the helter-skelter piling up of heirloom jewelry, Old Masters, and oriental rugs, the marrying off of American “dollar princesses” to the hard-up offspring of Europe’s decaying nobility, the exclusive watering holes in Newport and Bar Harbor, the prep schools, and gentlemen’s clubs fencing them off from hoi polloi, the preoccupation with social preferment that turned prized parterre boxes at opera houses and concert halls into deadly serious tournament jousts—seems silly. Or more to the point, it all appears as incongruously weird behavior in the homeland of the democratic revolution. And in some sense it was.

Yet this spectacle had a purpose, or multiple purposes. First of all, it was a time-tested way of displaying power for all to see. More than that was going on, however. It constituted the infrastructure of a utopian cultural fantasy by a risen class so raw and unsure of its place and mission in the world that it needed all these borrowed credentials as protective coloring. An elaborate camouflage, it might serve to legitimate them both in the eyes of those over whom they were suddenly exercising or seeking to exercise enormous power, and in their own eyes as well.

After all, many of these first- and second-generation bourgeois potentates had just sprung from social obscurity and the homeliest economic pursuits. Their native crudity was in plain sight, mocked by many. Herman Melville remarked, “The class of wealthy people are, in aggregate, such a mob of gilded dunces, that not to be wealthy carries with it a certain distinction and nobility.” As their social prominence and economic throw weight increased at an extraordinary rate—and, along with it, the most furious challenges to their sudden preeminence—so too did the need to fabricate delusions of stability and tradition, to feel rooted even in the shallowest of soils, to thicken the borders of their social insulation.

Caroline Astor, better known as “Mrs. Astor,” the doyenne of this world, whose grandfather-in-law had started out as a butcher, wrestled to express how such tensions might be resolved. Her family’s life was described by one observer this way: “The livery of their footmen was a close copy of that familiar at Windsor Castle and their linen was marked with emblems of royalty. At the opera they wore tiaras, and when they dined the plates were in keeping with imperial pretensions.”

Similar portraits were painted of many of the great dynastic families and their offspring; the Goulds, Harry Payne Whitney, the Vanderbilts, and others were depicted in ways that made them highly improbable candidates to form a socially conscious aristocracy. Mrs. Astor herself was once described as a “walking chandelier” because so many diamonds and pearls were pinned to every available empty space on her body.

Her relative John Jacob Astor IV, a notorious playboy, was chastised, along with his peers, by an Episcopal minister: “Mr. Astor and his crowd of New York and Newport associates have for years not paid the slightest attention to the laws of the church and state which have seemed to contravene their personal pleasures or sensual delights. But you can’t defy God all the time. The day of reckoning comes and comes not in our own way.” Some years later Astor went down with the Titanic. Another member of the clan declined an invitation by President Hayes to serve as ambassador to England on the grounds that it violated the family credo: “Work hard, but never work after dinner.”

Ward McAllister, the major-domo of the Social Register’s “400,” took a stab at coherence from another angle. “Now, with the rapid growth of riches, millionaires are too common to receive much deference; a fortune of a million is only respectable poverty,” McAllister said. “So we have to draw social boundaries on another basis: old connections, gentle breeding, perfection in all the requisite accomplishments of a gentleman, elegant leisure and an unstained private reputation count for more than newly gotten riches.”

But the “old connections” were as new and ephemeral as yesterday’s business negotiation, and “gentle breeding” for some didn’t even include full literacy or numeracy but did include copious spitting; the “accomplishments of a gentleman” would have to embrace every kind of shrewd dealing in the marketplace, or else the pickings would be scarce. And the tides of America’s volatile economy meant that no matter how high the sand dunes were built around the redoubts of “old money,” they could never resist for long the onrush of new money.

“Awful Democracy”

It was all, as one historian noted, a “pageant and fairy tale,” a peculiar arcadia of castles and servants, an homage to the “beau ideal” by a newly hatched social universe trying but failing to “live down its mercantile origins.” But this dream life was ill-suited to the arts and crafts of ruling over a society that at best was apt to find this charade amusing, at worst an insult. What was missing was an actual aristocracy.

Wall Street Brahmin Henry Lee Higginson, fearing “Awful Democracy”—that​ whole menagerie of radicalisms—urgently appealed to his fellows to take up the task of mastery, “more wisely and more humanely than the kings and nobles have done. Our chance is now—before the country is full and the struggle for bread becomes intense. I would have the gentlemen of the country lead the new men who are trying to become gentlemen.”

The appeal fell mainly on deaf ears. Many in this set were sea-dog capitalists, dynasty builders, for whom accumulation was a singular, all-consuming obsession. They reckoned with outside authority if they had to, manipulated it if they could, but just as often went about their business as if it didn’t exist. Bred to hold politics in contempt, one Social Register memoirist recalled growing up during the “great barbeque.” He was taught to think of politics as something “remote, disreputable, and infamous, like slave-trading or brothel-keeping.”

Together they concocted a world set apart from the commercial, political, sexual, ethnic, and religious chaos threatening to envelop them. An upper-class “white city” of chivalry, honor codes, and fraternal loyalties, mannered, carefree, and self-regarding, it was a laboratory of narcissistic self-indulgence, an ostensible repudiation of those distinctly bourgeois character traits of prudence, thrift, and money-grubbing.

Born into an age defined by steam, steel, and electricity, they attempted to wall themselves off from modernity in an alternate universe, part medieval, part Renaissance Europe, part ancient Greece and Rome, a pastiche of golden ages. The long nineteenth century had given birth to a plutocracy unschooled and indisposed to win the trust and preside over a society it feared. Instead, the plutocracy preferred playacting at aristocracy, simultaneously confirming all the popular suspicions about its real intentions and forming a society that had forsaken society.

Brute Force

The self-imposed aloofness and feudal pretentiousness of the upper classes left the institutions and cultural wherewithal of the commonwealth thin on the ground. An indigenous suspicion of overbearing government born out of the nation’s founding left the apparatus of the state strikingly weak and underdeveloped well past the turn of the twentieth century. All of its resources, that is, except one: force, rule by blunt instrument. The frequent resort to violence that so marked the period was thus the default position of a ruling elite not really prepared to rule. And of course it only aggravated the dilemma of consent. Those suffering from the callousness of the dominant classes were only too ready to treat them as they depicted themselves—that is, as aristocrats but usurping ones lacking even a scintilla of legitimate authority.

The American upper classes did not constitute a seasoned aristocracy, but could only mimic one. They lacked the former’s sense of social obligation, of noblesse oblige, of what in the Old World emerged as a politically coherent “Tory socialism” that worked to quiet class antagonisms. But neither did they absorb the democratic ethos that today allows the country’s gilded elite to act as if they were just plain folks: a credible enough charade of plutocratic populism. Instead, faced with mass social disaffection, they turned to the “tramp terror” and other innovations in machine-gun technology, to private corporate armies and government militias, to suffrage restrictions, judicial injunctions, and lynchings. Why behave otherwise in dealing with working-class “scum” a community of “mongrel firebugs”?

One historian has described what went on during the Great Uprising as an “interlocking directorate of railroad executives, military officers, and political officials which constituted the apex of the country’s new power elite.” After Haymarket, the haute bourgeoisie went into the fort building business; Fort Sheridan in Chicago, for example, was erected to defend against “internal insurrection.” New York City’s armories, which have long since been turned into sites for indoor tennis, concerts, and theatergoing, were originally erected after the 1877 insurrection to deal with the working-class canaille.

During the anthracite coal strike of 1902, George Baer, president of the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad and leader of the mine owners, sent a letter to the press: “The rights and interests of the laboring man will be protected and cared for… not by the labor agitators, but by the Christian men of property to whom God has given control of the property rights of the country.” To the Anthracite Coal Commission investigating the uproar, Baer proclaimed, “These men don’t suffer. Why hell, half of them don’t even speak English.”

Ironically, it was thanks in part to its immersion in bloodshed that the first rudimentary forms of a more sophisticated class consciousness began to appear among this new elite. These would range from Pullman-like Potemkin villages to more practical-minded attempts to reach a modus vivendi with elements of the trade union movement readier to accept the wages system.

Yet the political arena, however much its main institutions bent to the will of the rich and mighty, remained ostensibly contested terrain. On the one hand, powerful interests relied on state institutions both to keep the “dangerous classes” in line and to facilitate the process of primitive accumulation. But an opposed instinct, native to capitalism in its purest form, wanted the state kept weak and poor so as not to intrude where it wasn’t wanted. Due to this ambivalence, the American state was notoriously undernourished, its bureaucracy kept skimpy, amateurish, and machine-controlled, its executive and administrative reach stunted.

No society can live indefinitely on such shifting terrain, leaving the most vital matters unresolved. Even before the grand denouement of the Great Depression and New Deal arrived, an answer to the labor question was surfacing, one that would put an end to the long era of anti-capitalism. It would become the antechamber to the Age of Acquiescence.

Steve FraserSteve Fraser is the author of the just-published Mongrel Firebugs and Men of Property: Capitalism and Class Conflict in American History. He is a co-founder and co-editor of the American Empire Project.