In November 2017, soon after Raqqa was declared liberated from the Islamic State, 31-year-old journalist Amer Matar sat in front of his laptop in his home in Berlin, scrolling through images coming out of the city. ISIS had ruled Raqqa, Amer’s hometown, for three years. The “liberation” was bittersweet: A months-long military campaign by US-led forces had left thousands of civilians dead, 90 percent of the city’s population displaced, and much of the city reduced to rubble. In the photos, Amer struggled to recognize the streets he’d known his entire life. His home was destroyed. His neighborhood and his elementary school were completely demolished. The images offered no clues to the question that was at the front of his mind: Where was his brother Muhammad Nour?

On August 8, 2013, Muhammad went to film a demonstration outside a courthouse. Civilians were protesting the internal fighting between the various rebel groups contending for power there—among them Ahrar al-Sham, the Free Syrian Army, and the Al Qaeda affiliate then known as Nusra, now HTS—after the city’s liberation from government forces that spring. As people chanted, a car exploded near the crowd, killing dozens. Those who were far enough away to survive the attack were rounded up and arrested by members of the Islamic State, aka ISIS, which was also fighting over Raqqa and already controlled parts of it.

Amer began reporting on anti-government protests in 2011 and was arrested that year by the government. Soon after his release, he left for Germany, but after rebels seized control of Raqqa from the government in 2013, he frequently returned. In fact, he was traveling there on the day the bombing occurred, and arrived that night. So the next morning, Amer and his other brother, Mezar, went to the site of the attack to look for Muhammad, who was then 20. They studied the burned bodies that were still strewn around the street, looking for any clues that one of them could be their younger brother. Later that day, as they were examining the street again, they found Muhammad Nour’s camera, but there was no sign of him. They expanded their search to include Raqqa hospitals, turning up nothing until, several weeks after the bombing, they received a message from a man who had been held in an ISIS prison. He said he had seen Muhammad Nour inside.

Four years would pass, and Amer would hear nothing more about his little brother. When ISIS was finally driven out of Raqqa, Amer started to wonder: Thousands of ISIS detainees are still missing. Where were they?

This is when he decided to start a campaign called Where Are the Kidnapped by ISIS? People—largely from Raqqa, including some living in exile—joined the campaign to search for answers regarding the whereabouts of friends and family who had been detained by the extremist group.

According to the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, the Islamic State detained over 7,000 Syrians between 2013 and 2017. Charges included reporting human-rights abuses, participating in aid work, posting messages against the Islamic State on social-media platforms, and fighting for the Free Syrian Army. Hundreds of these detainees were publicly executed in Raqqa’s public squares.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

Ever since Muhammad’s disappearance, Amer’s mother, who had fled Raqqa in 2014, was sustained by the hope that her son would be freed and that she would see him again. However, as more news emerged of daily ISIS executions and as the US-led coalition began its bombing campaign against ISIS strongholds in the city, she began to lose hope. But now that the city was liberated, might there be a chance that he was still alive? Amer and other families with missing loved ones began reaching out to the US-backed Syrian Democratic Forces—the group that liberated Raqqa—to ask about detainees.

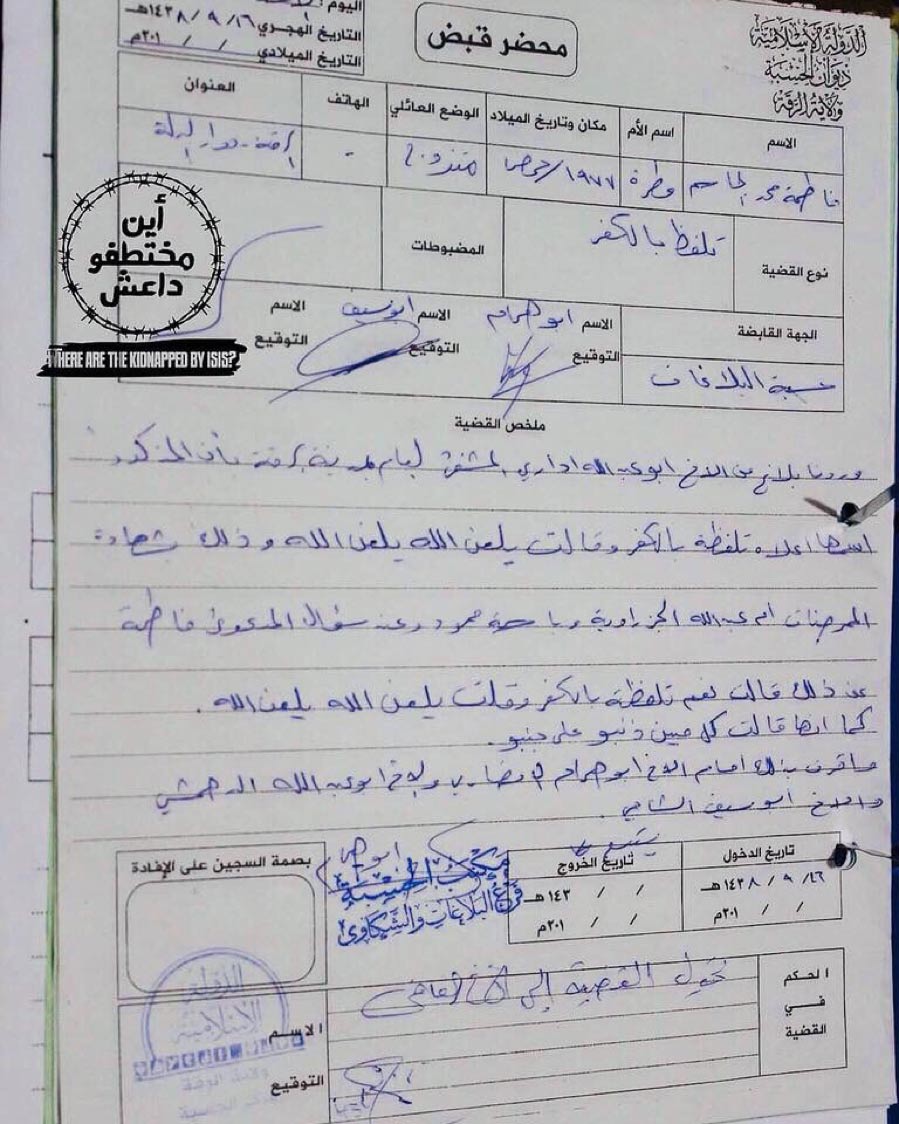

They learned that the jails were empty, but that ISIS had left its court files behind. The documents detailed the names of detainees, along with their charges and sentences. They also specified who had been executed and how. One example: “Fatima, born 1977, was executed because she cursed God out loud.” The walls of detainees’ cells were covered with love poems, messages from detainees to their families, and words of hate toward their captors. It was as if they knew that the group would be defeated one day, and that their families would receive the messages (one of them read, “I miss you, mother”).

Amer knew he had to try to find these people. “If the families don’t do something, no one will,” he told me. “It is like gluing pieces together. I don’t really understand where they have gone. This is a question that we have been trying to answer for months now. There are two possibilities: Either they are in mass graves somewhere, or they were taken as human shields when ISIS was withdrawing from Raqqa.”

Amer works closely with a team of activists based in Syria. They share a Google drive where they upload photos and videos of empty prisons, along with photos of missing persons sent by families. A goal of the project is to collect all the names of those who went missing, as well as those who were mentioned in the court documents.

Khalifa Alkhodr, who lives in Al Bab (in the Aleppo region, many miles from Raqqa), is also part of the team. “If I hadn’t escaped, I would have been one of these people that we are looking for,” he told me. On June 6, 2014, when Alkhodr was 19, he was traveling from Aleppo to Raqqa, where he was working on an article for a local newspaper, Henta—which was not shy about exposing the harsh realities of life under ISIS rule. (In fact, Henta’s founder, Naji Al Jerf, who also worked with the group Raqqa Is Being Slaughtered Silently, was murdered in Turkey in December 2015 by ISIS, which took credit for the assassination in a video.)

Halfway through the trip, near Al Bab, the van Alkhodr was traveling in was stopped at a checkpoint. A masked man with a thick Moroccan accent ordered Alkhodr to open the bag he was holding between his legs. After finding a camera that had been tucked under Alkhodr’s clothes, the man took Alkhodr out of the van and told the driver: “Drive. We are keeping him.”

“I will not lie to you and tell you I was scared,” Alkhodr told me. “I wasn’t. It’s as though I was numb, and the minute he pointed at me I knew I was done, so I just surrendered.” Alkhodr spent the following days in solitary confinement, which he left only to receive his daily share of torture and interrogation. “The main thing you have to do in solitary confinement is to make sure you are not losing your mind. I reached a point of loneliness where I wished someone else was getting tortured, just so I could hear screams. I just needed to hear another human being so I wouldn’t feel so alone. I wanted to see a full face. They wore masks, so I only ever saw eyes. It made me go crazy.”

That they were detained in an Islamist prison made it extremely hard for prisoners to find solace. Often detainees endure suffering by becoming closer to God. This, however, is not so easy in ISIS jails. One day, after his torture session, Alkhodr lay bleeding with his hands cuffed and legs bound. “I will pray and come back to you,” the torturer told him. Alkhodr told me, “I started to wonder if God was on his side or mine. I was convinced that God was on his side and it was I who was going to hell.”

After six months of detention, Alkhodr escaped. One day after sunrise prayers, a time when detainees were usually brought out for hard labor, he managed to flee through a window at the back of the building, sneaking through the alleys of Al Bab to avoid anyone who would recognize him. “My long hair and beard didn’t raise any suspicion around me. I made it safely to Aleppo through Izaz, but I couldn’t escape my fears. I felt that I was still in jail and that they were coming after me. I had to flee to Turkey.” Even in Turkey, though, Alkhodr was haunted by nightmares. “I was told, ‘If you don’t face your fears, you will forever stay in their jails.’”

Finally, when ISIS was defeated in Al Bab in February 2017, Alkhodr returned. He said he knew that if his detention “was my last memory from Syria I would forget everything else. My memories would fade and would be replaced by what I went through in jail. I couldn’t do it. They wanted us to hate our country, but we won’t.”

Today, Alkhodr accompanies Syria Civil Defense (more commonly known as the White Helmets) while they dig up mass graves in Al Bab and the surrounding area in order to find the people with whom he spent months in jail. He says that so far, they have uncovered 17 mass graves, with the majority of bodies in them reduced to skeletons. “Sadly, we don’t have any tools to identify these dead bodies. This is not something we, as regular civilians, could do.” Alkhodr says he wants to be able to notify families of those killed so that they can “bury them with respect. This would be the first step toward healing.” But without the help of international organizations with the right tools and expertise, he says, this will remain an impossible task.

When I asked Amer why he thinks international organizations are not getting involved, he replied, “Many human-rights organizations, like Amnesty and Human Rights Watch, reached out to me and asked about our efforts and the campaign. But they did not follow up, which is understandable. Syria, even in places that are relatively safer than other parts, is still dangerous.”

Amer tells me that the process of identifying DNA in mass graves may take years. In addition to the graves, he informs me, “there are dead bodies still buried under the rubble from the US-led military campaign.” He adds, “Sadly, these families, including mine, can’t do anything but wait.” The only thing they can do now, he says, is to prepare, collect evidence, and preserve it until human-rights organizations can provide further assistance.

Curious as to whether he is hopeful about Raqqa following the “liberation,” Amer bluntly replies, “ISIS was defeated, but the horror of this group will haunt Syrians for years, probably for decades.”