Here is one iron law of the Internet: a social network’s emphasis on monetizing its product is directly proportional to its users’ loss of privacy.

At one extreme there are networks like Craigslist and Wikipedia, which pursue relatively few profits and enable nearly absolute anonymity and privacy. At the other end of the spectrum is Facebook, a $68 billion company that is constantly seeking ways to monetize its users and their personal data.

Facebook’s latest program, Graph Search, may be the company’s largest privacy infraction ever.

Facebook announced Graph Search in mid-January, but it has not officially launched. According to company materials and some independent reports, however, the program cracks open Facebook’s warehouse of personal information to allow searching and data-mining on a large portion of Facebook’s 1 billion users. Users who set their profiles to “public” are about to be exposed to their largest audience ever.

Facebook sees this as the future. In a video announcing the program, Mark Zuckerberg, the company’s founder and CEO, touts Graph Search as one of three core pillars of “the Facebook ecosystem.”

The financial incentives are clear. Google, which is triple the size of Facebook, makes most of its revenue through search ads. So while the companies host the two most-visited sites in America, Google squeezes more money out of users in less time. Search provides a way for Facebook to sell more to its active users and, of course, to sell its users to others. That’s where Tom Scott comes in.

Scott, a 28-year-old British programmer, prankster and former political candidate—he ran on a “Pirate” platform of scrapping rum taxes—has launched his own prebuttal to Graph Search. His new blog, “Actual Facebook Graph Searches,” uses a beta-test version of the feature to show its dark side.

With a few clicks, Scott shows how Graph Search provides real names, and other identifying information, for all kinds of problematic combinations, from the embarrassing and hypocritical to  ready-made Enemies Lists for repressive regimes. His searches include Catholic mothers in Italy who have stated a preference for Durex condoms and, more ominously, Chinese residents who have family members that like Falun Gong. (He removed all real names, but soon anyone can run these searches.)

ready-made Enemies Lists for repressive regimes. His searches include Catholic mothers in Italy who have stated a preference for Durex condoms and, more ominously, Chinese residents who have family members that like Falun Gong. (He removed all real names, but soon anyone can run these searches.)

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

“Graph Search jokes are a good way of startling people into checking their privacy settings,” says Scott, who was randomly included in a test sample for early access to the program. “I’m not sure I’m making any deeper point about privacy,” he told The Nation. That may have helped make Scott’s lighthearted effort so effective.

Within a few days after launching, Scott’s blog went, yes, viral. He says it has drawn over a quarter-million visitors, thanks to a wide range of web attention, and it has stoked more scrutiny of Facebook.

Mathew Ingram, a technology writer and founder of the digital mesh conference, argues that Scott’s search results gesture at a value beyond traditional “privacy.” Some pragmatists and Facebook defenders stress that the information in these search results was already surrendered by the users, so we should criticize them, not the technology. (You know, Facebook doesn’t kill privacy, people do.) But Ingram rebuts this reasoning by invoking a paradigm from philosopher Evan Selinger, who argues that these questions actually turn on the assumptions and boundaries of digital obscurity.

“Being invisible to search engines increases obscurity,” writes Selinger. “So does using privacy settings and pseudonyms, [and] since few online disclosures are truly confidential or highly publicized, the lion’s share of communication on the social web falls along the expansive continuum of obscurity: a range that runs from completely hidden to totally obvious.”

Facebook’s search engine is another step in its long pattern of promising a “safe and trusted environment” for empowered sharing — Zuckerberg’s words — while cracking open that Safe Space for the highest bidder. So the access and context of that space is crucial. After all, many people would consent to sharing several individual pieces of personal information separately, while balking at releasing a dossier of all that same information together. The distinction turns more on the principles of obscurity and access than binary privacy—a concept that has faded as social networks proliferated—and even draws support from the literature on intelligence and espionage.

The CIA, for example, has long subscribed to the Mosaic Theory for intelligence gathering. The idea is that while seemingly innocuous pieces of information have no value when viewed independently, when taken together they can form a significant, holistic piece of intelligence. The Navy once explained the idea in a statement on government secrecy that, when you think about it, could apply to your Facebook profile: Sometimes “apparently harmless pieces of information, when assembled together, could reveal a damaging picture.”

Facebook’s incentives are, almost always, to keep assembling the information and revealing that picture.

—

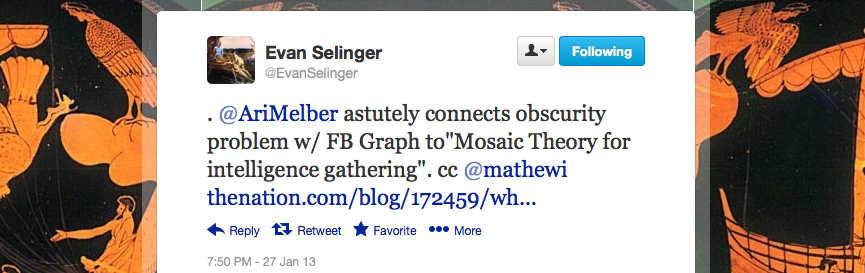

UPDATE: Philosophy professor Evan Selinger responds to this article on Twitter:

"Obscurity: A Better Way to Think About Your Data Than 'Privacy,'" Selinger's essay co-authored with Woodrow Hartzog, is here.