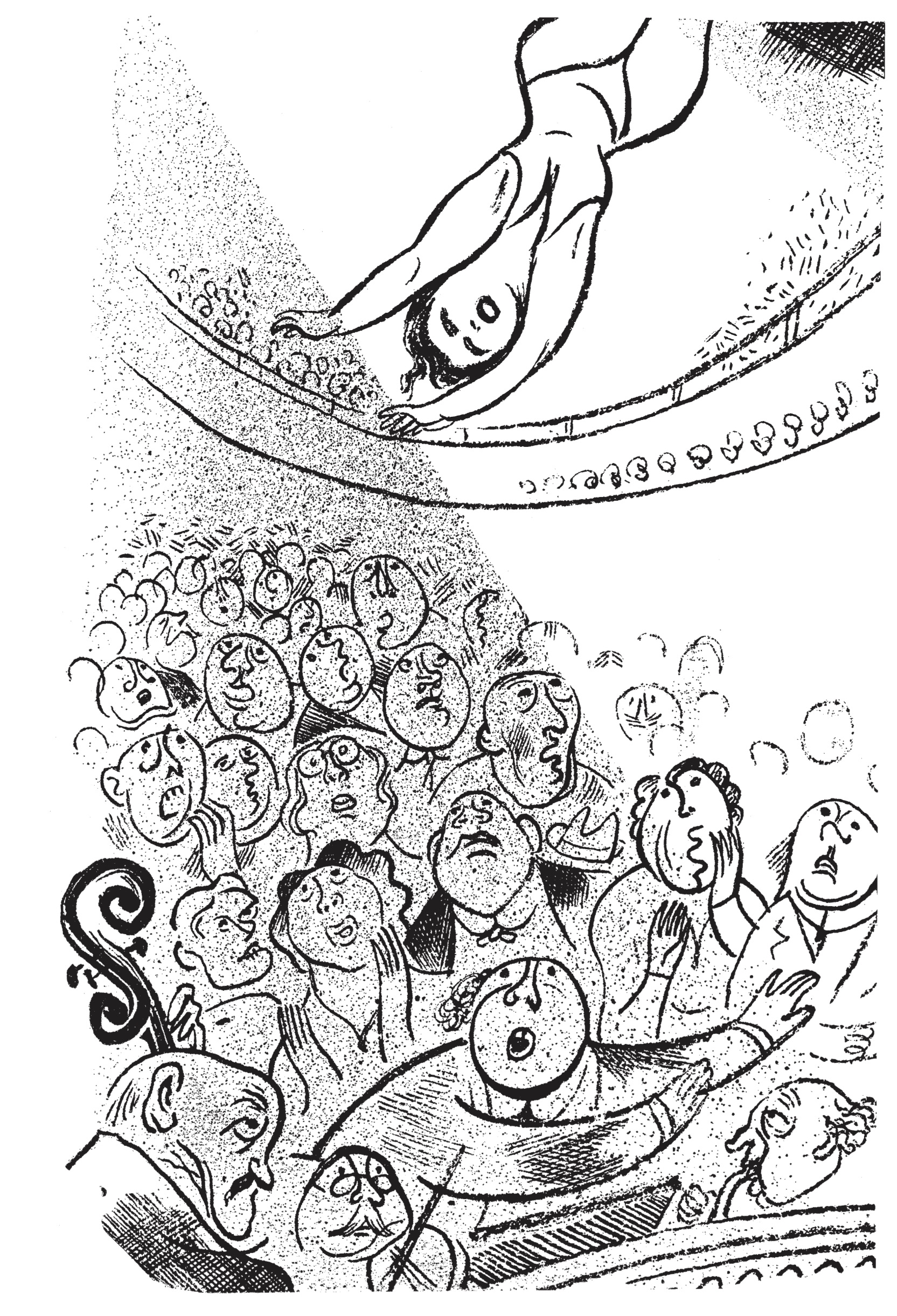

William Gropper Alay-Oop.(Courtesy of New York Review Comics)

William Gropper is not especially well remembered today, but to the extent that he is, it’s as a political cartoonist. From 1917, when he joined the staff of the New York Tribune, to the mid-1940s, he drew thousands of biting images accompanied by unflinching captions for publications as varied as Vanity Fair, the Marxist New Masses magazine, and the Yiddish communist newspaper Morgen Freiheit. He lambasted the US government and the Nazis with equal fervor, fueled by political beliefs and personal experience. As a Jew and a committed socialist who was blacklisted by the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1953, he had a front-row view of the workings of injustice and tyranny.

What’s less known is that Gropper worked in more traditional high art forms too, namely paintings and prints, and did so long after he stopped making cartoons, until his death in 1977. Some of what he made is surprisingly benign, like idyllic mail-themed murals for a post office in Freeport, New York, and a massive mural showing the construction of a dam for the Department of the Interior. He also had an abiding interest in American folklore, creating pictures of heroes such as Johnny Appleseed and Paul Bunyan as well as a map of the country covered with historical and mythical characters, scenes, and names.

Stylistically, there are similarities between Gropper’s political cartoons and his fine art, but in terms of content, it’s almost hard to believe the same person made them. Despite the socialist bent to some of the art (think of those dam builders working in unison, one with a red handkerchief in his pocket), much of it feels nostalgic and almost patriotic—a strange sentiment for someone who was ruthlessly critical of the powers that be. Yet there’s a certain logic to the contradiction: When you believe in something, like a nation, you inevitably want it to be better. This duality makes his work all the more interesting. He wasn’t just a brilliant outrage machine; the breadth of his art was considerably more complex.

A new book offers a chance to expand our view of Gropper the artist. This summer, New York Review Comics released an edition of Alay-Oop, his only full-length narrative work. The book was first published in 1930 but never sold well and had long been out of print. It tells the story of three variety show performers and a failed marriage in hand-drawn pictures (plus six intertitle pages), making it a proto–graphic novel and an exciting addition to the comics canon. It’s also remarkable for bridging the two sides of his creativity so effectively. The roughly 200-page volume reads like social commentary as well as a fable. Its images are sketchlike and cartoonish, but the lack of words lends it a certain openness to interpretation that’s more a hallmark of fine art. Paging through Alay-Oop feels like finding a missing link in Gropper’s career.

According to the publisher’s description, Alay-Oop “presents an unusual love triangle”—but I’m not so sure that’s the case. The book does have three unnamed protagonists: a pair of acrobats whose act is titled “Alay-Oop” and a singer who, judging by his stoutness and the black hole that his mouth becomes when he performs, specializes in opera. They’re all part of a vaudeville show in an unidentified city. At the start of the story, the singer watches the acrobats and becomes infatuated with the female member of the duo. He woos her by promising a life of financial security. She returns to the theater to tell her stage partner she’s quitting the gig and getting married. He accepts the news rather passively and escorts the new couple out the door.

Fast-forward to sometime years later. The woman is staying home to raise twins. Her former partner is still around, stopping by to play with the kids, which makes the husband jealous. During an especially severe episode of rage—although no physical abuse is shown—she takes her children and runs. The husband sneaks away, too, leaving the landlady to clean up the mess. From there we pan out to a nighttime view of the city and then a coda: The “great singer” is using his musical skills to hawk fruit on the street; the “swinger,” the male acrobat, is working in construction; and Alay-Oop is now an act performed by the woman with her kids.

These are the contours of the story, which Gropper delivers through cannily expressive black-and-white art. When the singer falls for the acrobat, his mouth and body become heart shaped; when he screams at her, he turns into a morass of jagged, wavy lines. Gropper’s drawings can be busy and bursting, or they can be beautifully spare. The first seven images spotlight the acrobats as they soar through the open space of the otherwise blank page.

Nevertheless, the outline of the narrative remains just that—an outline—without the details of dialogue or narration to fill it in. Are the characters of Alay-Oop actually in a love triangle, or are the acrobats strictly colleagues and friends? When the husband gets jealous, he envisions his children with the male acrobat’s mustache on their faces, implying infidelity. But we have no way of knowing whether that’s a real possibility or simply a figment of his imagination. That ambiguity is part of what makes Alay-Oop such an engaging read. The art offers a legible accounting of the events, but we’re mostly left to invent the psychological context ourselves. Call it “choose your own backstory.”

Where this manifests most clearly is in a dream sequence that takes place the night before the proposal. The female acrobat goes to sleep and finds herself plunged into a surreal, Picasso-shaded world that alternately appears underwater and among the stars. Bodies break apart, and stout horses float by, appearing especially virile. The episode ends with our heroine lying on her back, arms above her head, her face locked in an expression of wonder. She looks, at least to this viewer, as if she’s been invaded by some force or creature that only she can see. Gropper’s drawing of her when she wakes up groggy the next morning is a marvel of empathy: Her apparent confusion about what happened reflects our own.

Whether one considers Alay-Oop a graphic novel or simply a precursor to the genre, it was in many ways a product of its time. In the previous decade, the Belgian artist Frans Masereel and American artist Lynd Ward released woodcut novels to great success. They were black-and-white, wordless tales with heavily stylized, graphic art, a socialist bent, and healthy doses of angst and melodrama. The same year that Alay-Oop came out, the cartoonist Milt Gross published a parody of the form titled He Done Her Wrong (subtitled The Great American Novel and not a Word in It—No Music, Too), a tale of true love (interrupted by a villain) that featured hand-drawn images in the vein of the comic strips he made for newspapers.

Gropper’s take on the woodcut novel was equally loose and modern in style. “The works of Masereel and Ward, drawn only a few years prior, look like they were made in a medieval monastery centuries ago; Gropper and Gross’s books look like they were just drawn at a bustling coffee house, the ink still wet,” writes cartoonist James Sturm in the introduction to the new edition of Alay-Oop. As Sturm points out, however, Gropper was not satirizing the form so much as reimagining it. There’s class-driven conflict in his story but not much anguish or moral condemnation. No one gets a comeuppance or is crushed in the gears of society; instead, the story resolves with an abrupt, neat ending that implies that life simply goes on.

What’s more, the protagonist is a woman, which was rarely the case in wordless novels. And in the dream sequence, Gropper really goes off script. Amid a story built around action and reaction, he takes out 10 pages to give us a glimpse of the acrobat’s subconscious—and one that’s far too wild to be useful to the plot. What it does is make her more than just a type, which in this kind of tale she could easily become. We don’t know her name or what that thing she dreams about is, but we know she has a complex inner life.

Clearly, Gropper’s political views and personal experiences informed his story. As a socialist, not only was he likely invested in working-class people; he was one of them. His parents supported him and his five siblings with grueling jobs in the garment industry. (His father studied at universities in Europe and learned eight languages but couldn’t find better work in the United States.) In 1911, when Gropper was 13 years old, his aunt died in the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire. He seems to have been attuned, at least in some small way, to the extra burdens borne by women in these situations. “The sweatshop gave us our livelihood but robbed us of our mother,” he once said.

In Alay-Oop, he rewrites the script. Work may be necessary for the acrobat, but it’s also part of her identity and something that brings her joy. Rather than close with a new romance or a reunion with her former partner, the book leaves her smiling as she puts on an act with her kids. As it turns out, what she needed all along was self-sufficiency. This is a socialist message, to be sure, but also a feminist one. Alay-Oop is a strikingly modern tale of a woman’s journey to independence. That’s part of what makes its rediscovery in 2019 so thrilling.

It’s also bittersweet. Gropper went on to produce more cartoons, prints, and paintings, but after 1930, he never created another book. Maybe he thought Alay-Oop was, in its own way, slight, so far removed from the force of his political work. Or perhaps the commercial failure of it simply ensured that picture novels would remain a blip in his career. Now, with the advantage of nearly 90 years, we can see how inventive and artistically successful it was. This book, which for so long remained forgotten, may yet help ensure that its creator isn’t.

Jillian SteinhauerTwitteris a critic and reporter who covers the politics of art and comics. She won a 2019 Andy Warhol Foundation Arts Writers grant for short-form writing.