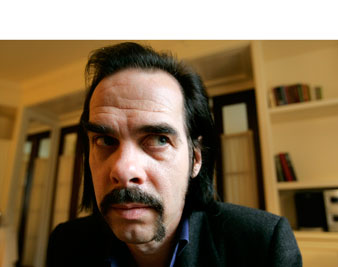

Mike Segar/ReutersNick Cave, 2006

Mike Segar/ReutersNick Cave, 2006

When Nick Cave debuted in 1978, it was as the sallow, possessed frontman of the Birthday Party, gothic shock troops from Australia with orders to antagonize England’s petrified punk circuit. Bad timing. Soon after these brutes arrived in London in the early ’80s the national appetite turned to glitzy synth pop, something better suited to the megabucks mood of false optimism that greeted the early days of the Reagan-Thatcher years. The Birthday Party splintered in 1983, leading Cave to form what would become his longest-running band, the Bad Seeds, a group that had little in common with the chipper New Wave of the early MTV era. The Bad Seeds crafted a creepy fusion of American roots music and European experimentalism, as if the Elvis who grew up on country blues had been force-fed astringent Modernist operas during his Army-sponsored vacation in West Germany. And like New World bluesmen and Old World composers, Cave dealt in the kind of romantic myths in which someone invariably winds up on the slab.

Cave’s basic intransigence helped him survive the 1980s; albums like From Her to Eternity (1984) and The First Born Is Dead (1985) found him peeling back the soft belly of the era’s pop to get to its darker pleasures, a musical David Lynch with the brimstone tone of Cormac McCarthy. In 2003, after more than a dozen albums studded with coal-black observations on male-female folly, Cave and the Bad Seeds released “Babe, I’m on Fire,” fifteen minutes of electrified holy-roller gospel shaking down a deconsecrated church. The song’s lyrics are little more than a catalog: Cave spins one jolting description of some strange, supernatural or just plain seedy character after another, like the “demented young lady who’s roasting her baby.”

Halfway through recounting this rogues’ gallery, he slips in a seemingly throwaway jibe about an “old rock and roller with his two-seater stroller,” a self-deprecating in-joke at the expense of this father of twins. But rock has always found domesticity somewhat complicated. Embracing the traditional responsibilities that come with age tips over the wobbly (if entertaining) fallacy that you can be an angry young man in perpetuity. Acknowledging that you’re growing old in your music while retaining some of rock’s youthful energy is a precarious business. This was especially true for someone whose early persona was the louche thug winking his way through foul play, as with the infamous gallows humor of the Birthday Party’s “Six Inch Gold Blade,” in which he stuck the titular knife “in the head of a girl.” Even after Cave traded the barbarous comedy of the Birthday Party for the graver, more adult voice of the Bad Seeds, he hardly came off in song like the kind of guy who took the kids shopping at Whole Foods on Saturday morning.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

Yet over the past ten years, in interviews and songs, Cave has insisted that he is that guy, repeatedly declaring himself to be the kind of hardworking dad you’d call all-American if he wasn’t an antipodean expat now residing near the English seaside. Fans wondered if paternity and married life really suited the apocalyptic vibe that animated Cave’s early material, and indeed his initial response to his newfound maturity was to forgo the Bad Seeds sound for a series of straight-faced, almost self-serious ballads. Folks who claimed Cave had lost his way, or at least his sense of humor, weren’t entirely wrong. Even when listening to a gorgeous love song like “Into My Arms,” from The Boatman’s Call (1997)–which found Cave dallying in the lower reaches of the English pop charts–it was hard not to wistfully recall the man who was once more likely to write a creepy mash note to a circus carny than to bend on one knee and pledge fealty to his lady fair.

Maybe he got fed up with playing slow or decided that reconnecting with his musical id would be cheaper than therapy. Either way, in recent years Cave has slowly yet forcefully renewed his devotion to rock’s cheaper thrills while laying bare the liver spots, erectile dysfunction and impotent fears about the ruined planet his offspring stand to inherit. That’s his trick: with a wink and a leer, he inflates these middle-aged laments to the same mythical, near ridiculous proportions he once reserved for murderous backwoods boys. And he does it over a racket that offers a respectable third way for those who recognize the potential silliness of a fiftysomething father kicking out the jams while not necessarily wanting to cede the stage to those under 30. Cave’s unique, self-lacerating sense of humor helps him avoid the self-parody of rock’s sexagenarian cocksmen and middle-aged do-gooders preening across stadium stages.

Even as a young man, Cave lurked in the shadows of the world inhabited by the Jaggers and Stings. Most career underground types his age wind up banished to the world of public radio, a venue where his noisy cheek and unrepentant ribaldry makes him an outcast among genteel folkies and old punks turned singer-songwriters. But occasionally he manages to make ripples in the mainstream. Last year, he recorded a frequently astonishing little album with a new band of old familiars called Grinderman; their self-titled debut offered ramshackle rock built from little more than bile and feedback. Ragged yet catchier than anything Cave had recently put his name to, it also earned him his best press in ages.

Much of the buzz was thanks to the song “No Pussy Blues,” Cave’s finest example of how someone on the wrong side of 40 can vent his age-specific woes using rock’s pubescent palette of big beats and blaring riffs (even if these riffs happened to be played on an electric bouzouki instead of the expected acoustic guitar or grand piano). This nasty ode to self-abasement opens with the narrator, a desperate, decrepit old codger angling for the sexual favors of a woman half his age, squirming under the hateful flashbulb glare of “all the young and the beautiful/With their questioning eyes.” Jilted and flailing, he doesn’t shrink from view like any mortal, mortified man might. Instead, he itemizes the humiliations he’s put himself through–he starts with agreeably undertaking household chores, only to wind up pathetically playing the tough guy–in the hopes that the woman will relieve his pent-up lust, which is finally uncorked by a speaker-shredding whoop from the backing band.

The rest of Grinderman firms up Cave’s guiding philosophy: that he can have the brutality and the tenderness, the wit and the knowing stupidity, the sex crimes and the family values–all of ’em, on one record. He offers a freewheeling abundance of moods when most of rock’s ballyhooed next big things struggle to articulate just one. On the overstuffed Abbatoir Blues/The Lyre of Orpheus (2004), he split his hard and soft sides into an ungainly two-album set; the new Dig Lazarus Dig!!!, his latest collaboration with the Bad Seeds, ties the halves together with a big black bow.

Dig isn’t as funny or as fierce as Grinderman, though it has its moments. The title song revives the biblical character who “never asked to be raised up from the tomb” as a modern-day sad sack named Larry. Stumbling from one big-city misfortune to the next, he has once again landed six feet under by the song’s end, but only after a layover in the madhouse. Though not quite a Cave stand-in, Larry is certainly as befuddled as the man in “No Pussy Blues,” another aged fellow who must contend with a world where “mirrors became his torturers.” The song is quintessential Cave: heavy-handed religious imagery played for laughs and sonic clichés (in this case a lurching glam stomp) pumped up to burlesque, a deep vein of fatalism pulsing underneath.

Cave never was one for overt stabs at politics, but on Dig‘s best tune, “We Call Upon the Author,” he gripes about “the rampant discrimination, mass poverty, Third World debt, infectious disease, global inequality and deepening socioeconomic divisions.” It’s not quite a turn to protest; the song gets off on societal collapse as much as it bemoans it, offering few solutions for its reversal. While he frets over his and his children’s future, he is visited by a friend who brings him a book of “Holocaust poetry” and warns about “the rain,” an echo of Bob Dylan’s nuclear precipitation and of Travis Bickle waiting for the Almighty to wash society into the gutter. Relax, says the fatalist in Cave; it’ll all be over soon. Here’s a killer groove while you wait.

Playing the end of the world for thrills may make for bad activism, but it’s certainly entertaining. And despite the immense pleasure to be derived from Cave’s wordplay, his chosen form of entertainment is rock ‘n’ roll; Dig enthusiastically shreds his poetry with rhythm and noise. “Today’s Lesson,” “Albert Goes West,” “Midnight Man”–these songs lack the small-combo violence and combustibility of Grinderman, but their squalls of electric guitar and garage-band hip shake will be welcome to those who found themselves sleeping through the dignified melodies Cave was composing only a few years ago. (It’s not all nails on a blackboard; there’s also some flute and violin if you prefer a caress to having your ears boxed.)

Nick Cave is hardly the first musician to cross rock’s art and pop wires, messily mix sacred and profane or feign teenage kicks to define adulthood. But he’d be sui generis even if popular music were overrun with 50-year-olds in the throes of their second or third creative rejuvenation–unless they too were jackleg biblical scholars cracking filthy jokes about themselves to sleazily erotic punk-blues. If anything, experience has made his music fiercer. Who knows how vicious he’ll have gotten by the time he’s blowing out sixty candles on his birthday cake?