Johnny Randle, a 74-year-old African-American resident of Milwaukee, moved to Wisconsin from Mississippi in 2011, the same year the state legislature passed a law requiring a government-issued photo ID to cast a ballot. Randle, with the help of his daughter, petitioned the DMV to issue him a free ID for voting because he could not afford to pay for his Mississippi birth certificate.

After a five-month “adjudication process,” the DMV denied his request. His daughter ultimately tracked down his Mississippi birth certificate, but the name listed, Johnnie Marton Randall, did not match the name he’d used his entire life, Johnny Martin Randle. The DMV said that he would either need to correct his name through the Social Security Administration and get a new Social Security card reflecting the name on his birth certificate or go to court to “change” his name and “provide court documents reflecting that your name has legally been changed to read as ‘Johnny M Randle.’” But Randle worried that any change to his Social Security information might interrupt the monthly disability payments he survives on. (This account comes from a new lawsuit challenging Wisconsin’s voting restrictions filed by Democratic lawyer Marc Elias, Hillary Clinton’s campaign counsel.)

Randle was forced to choose between his livelihood and his right to vote. As of the April 5 presidential primary, he is still not able to vote in Wisconsin. After voting without incident in the formerly Jim Crow South, he was disenfranchised when he moved to the North. Stories like Randle’s are why the Wisconsin Supreme Court dubbed the voter ID law a “de facto poll tax” and it was blocked in state and federal court until a panel of Republican-appointed judges reinstated the measure in 2014.

Randle is one of 300,000 registered voters in Wisconsin, 9 percent of the electorate, who do not have a government-issued photo ID and could be disenfranchised by the state’s new voter-ID law, which is in effect for the first time in 2016. Wisconsin, one of the country’s most important battleground states, is one of 16 states with new voting restrictions in place since 2012. The five-hour lines in Arizona were the most recent example of America’s election problems. Wisconsin could be next.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →Randle’s account is hardly unique in Wisconsin. The lead plaintiff who challenged the voter-ID law, 89-year-old Ruthelle Frank, has been voting since 1948 and has served on the Village Board in her hometown of Brokaw since 1996, but cannot get a photo ID for voting because her maiden name is misspelled on her birth certificate, which would cost $200 to correct. “No one should have to pay a fee to be able to vote,” Frank said.

Others blocked from the polls include a man born in a concentration camp in Germany who lost his birth certificate in a fire; a woman who lost use of her hands but could not use her daughter as power of attorney at the DMV; and a 90-year-old veteran of Iwo Jima who could not vote with his veterans ID.

Noted voting-rights expert Allan Lichtman, a professor of history at American University, says the Wisconsin voter-ID law “represents the first time since the era of the literacy test that state officials have told eligible voters that they cannot exercise their fundamental right to vote—not in the next election, probably not ever.”

There is a clear racial disparity in terms of who is most impacted by the law. In 2012, African-American voters in Wisconsin were 1.7 times as likely as white voters to lack a driver’s license or state photo ID, and Latino voters were 2.6 times as likely as white voters to lack such ID. More than 60 percent of people who’ve requested a photo ID for voting from the DMV have been black or Hispanic, according to legal filings.

The law also targets students. Student IDs from most public and private universities and colleges are not accepted because they don’t contain signatures or a two-year expiration date (compared to a ten-year expiration for driver’s licenses). “The standard student ID at only three of the University of Wisconsin’s 13 four-year schools and at seven of the state’s 23 private colleges can be used as a voter photo ID,” according to Common Cause Wisconsin.

That means many schools, including the University of Wisconsin-Madison, are issuing separate IDs for students to vote, an expensive and time-consuming process for students and administrators. Students who use the new IDs will also have to bring proof of enrollment from their schools, an extra burden of proof that only applies to younger voters.

“They’re trying to suppress the votes of students,” says Analiese Eicher, program director at One Wisconsin Now and a graduate of UW-Madison. “There’s no other reason.”

Getting an ID from the DMV, which has very limited hours, is even more inconvenient. Writes Emily Mills in the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel:

Right now, the dirty little open secret of Wisconsin is that just 31 of our 92 DMVs maintain normal Monday through Friday business hours. Forty-nine of them operate only two days a week. One, in Sauk City, is open for just a few days a year. Only two are open at 5 p.m., and just three are open on weekends. For the whole state.

To exacerbate matters, Wisconsin has allocated no money to educate voters about the new law, as required by the legislation, and Republicans have dismantled the non-partisan Government Accountability Board in charge of supervising elections.

This is all happening despite the fact that voter impersonation, the stated rationale for the law, is virtually nonexistent in Wisconsin. “The defendants could not point to a single instance of known voter impersonation occurring in Wisconsin at any time in the recent past,” wrote Judge Lynn Adelman of the US District Court in Wisconsin. “It is absolutely clear that Act 23 will prevent more legitimate votes from being cast than fraudulent votes.” (Adelman was reversed by the US Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit, who ruled that Wisconsin’s law was “materially identical” to the Indiana voter-ID law approved by the Supreme Court in 2008, even though Wisconsin’s bill is significantly stricter and impacts many more voters. See Judge Richard Posner’s dissent for more detail.)

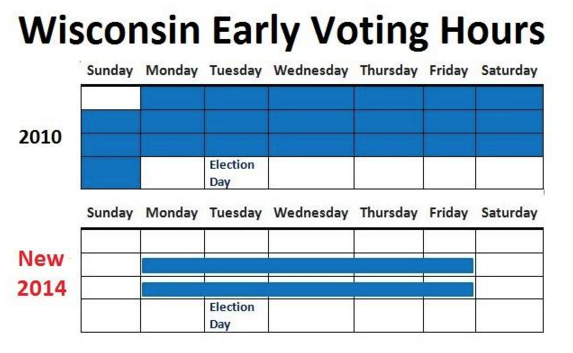

The voter-ID law is just one of many new voting restrictions passed by Republicans in Wisconsin since 2011. Most notably, the state legislature also eliminated early-voting hours on nights and weekends (GOP State Senator Glenn Grothman said he wanted to “nip this in the bud” before early voting in cities like Milwaukee and Madison spread to other parts of the state) and made it virtually impossible for grassroots groups to conduct voter-registration drives.

From the legal challenge filed by Elias:

Since 2011, the State of Wisconsin has twice reduced in-person absentee (“early”) voting, introduced restrictions on voter registration, changed its residency requirements, enacted a law that encourages invasive poll monitoring, eliminated straight-ticket voting on the official ballot, eliminated for most (but not all) citizens the option to obtain an absentee ballot by fax or email, and imposed a voter identification (“voter ID”) requirement.

“There have been so many anti-voting laws in this state, it’s hard to keep track,” says Eicher.

Wisconsin has historically run elections better than almost anywhere in the country, with consistently high voter turnout and reforms like Election Day registration in place since the 1970s. All that changed when Scott Walker and the Republican legislature took over the state in 2011.

“It’s just, I think, sad when a political party—my political party—has so lost faith in its ideas that it’s pouring all of its energy into election mechanics,” Republican State Senator Dale Schultz, a rare dissenter, said in 2014. “We should be pitching as political parties our ideas for improving things in the future rather than mucking around in the mechanics and making it more confrontational at our voting sites and trying to suppress the vote.”