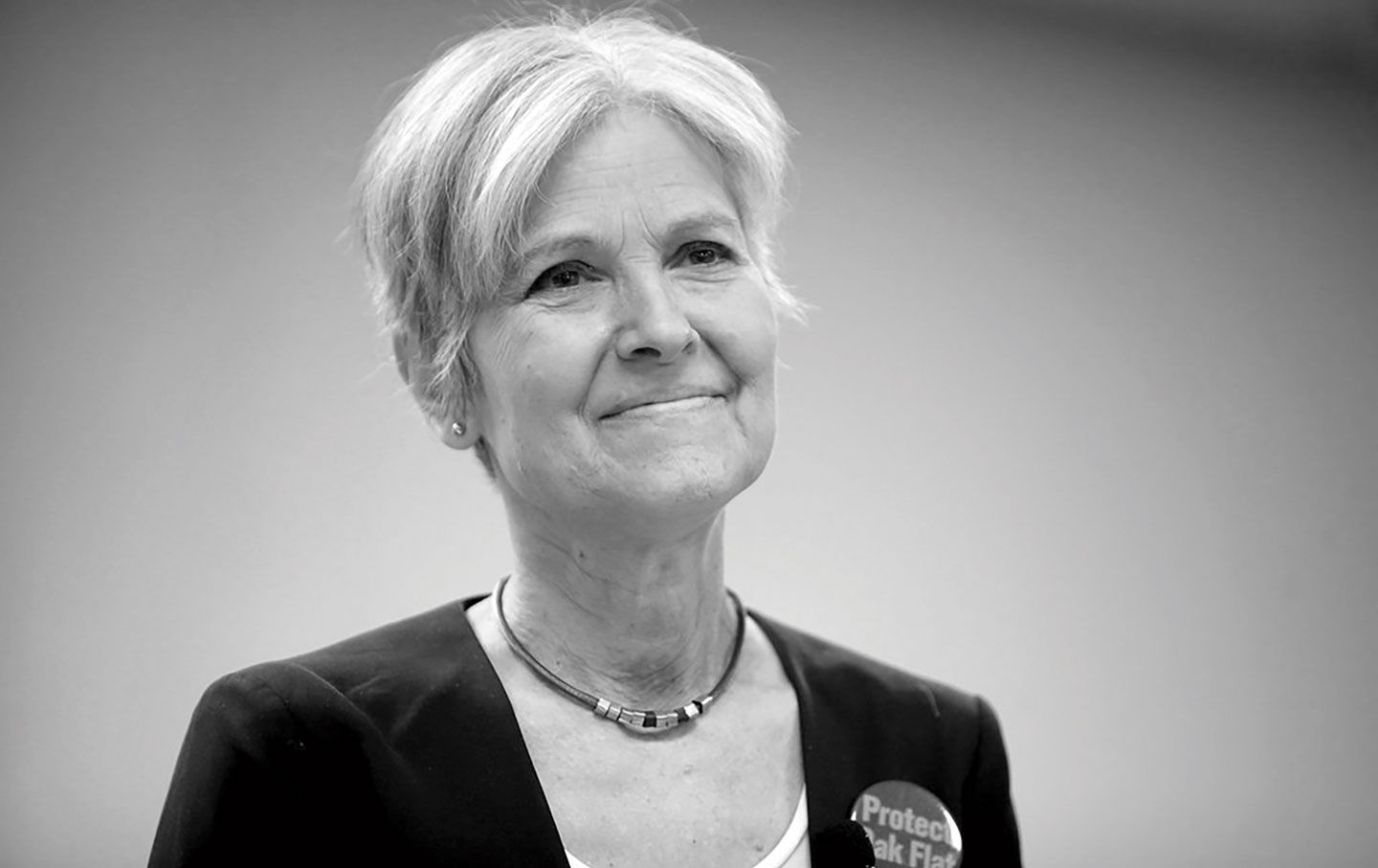

If the last three presidential elections are any guide, 75 to 90 percent of those who say that they’re planning to vote for Green Party candidate Jill Stein in November won’t follow through. Yes, there are some dedicated Green voters, but much of the party’s support is an expression of contempt for the Democrats that evaporates in the voting booth. I’m a registered independent and a supporter of the Working Families Party, and my disdain for the Greens springs from my own experience with the party. I agree with much of the Greens’ platform, but when I went to Green Party meetings, I found a wildly disorganized, mostly white group that was riven with infighting, strategically inept, and organized around a factually flawed analysis of American politics. There are effective Green parties in Europe, but ours is a hot mess. And while the Greens’ bold ideas are attractive, what’s the point of wasting one’s time and energy on such a dysfunctional enterprise?

The Green Party claims to have “at least” 137 members in elected office. That might sound respectable, but that’s 43 fewer than it had in 2003. And there’s a reason that number is shrinking: The Greens focus the lion’s share of their limited resources on getting their quixotic presidential campaigns on the ballot rather than on building the party from the bottom up. One could argue that running presidential campaigns earns candidates like Stein and David Cobb (for whom I voted in 2004, in a safe state) more media attention, but that hasn’t resulted in a growing number of seats for the Greens. The hyper-local Working Families Party, which backed 111 candidates in New York State alone last year—71 of whom were successful—makes headlines by winning fights over things like minimum-wage hikes and school funding rather than running symbolic presidential campaigns.

The Green Party’s primary pitch to voters on the left is that there still isn’t a dime’s worth of difference between the two major parties. When Ralph Nader made that claim in 2000, there was a kernel of truth to it. Today, that claim requires a great deal of dishonesty to make. By every measure, Democrats and Republicans have moved toward their respective ideological poles since the 1990s. According to Pew Research, since 2011, the most conservative Democrat on Capitol Hill has still been more liberal than the most liberal Republican, based on their aggregate voting records. It’s also true of the Democratic base—according to Pew, the share of Democrats who hold “mostly or consistently liberal” views almost doubled between 1994 and 2014. And it’s true of the 2016 party platform, which Bernie Sanders, among others, hailed as the most progressive in the party’s history. Today’s low-information voter is as likely to be aware of the major-party candidates’ differences as a highly engaged voter was in the mid-1970s.

You might notice that Greens tend to steer the conversation away from the myriad issues—health care, education, abortion, gun control, climate change, and on and on—where the Democrats and Republicans are diametrically opposed, and toward foreign policy and national security, where there really is significant overlap between the major parties’ policies. I agree with the Greens on many of those issues. But they’re not sufficient to substantiate the claim that there’s no difference between the Democrats and Republicans at all.

And the Greens’ critique of the Democrats is often unmoored from reality. Stein goes beyond (rightly) criticizing the Obama administration’s strategy in the aftermath of the 2009 coup in Honduras by charging that then–Secretary of State Hillary Clinton gave it “a thumbs-up.” (Not only did the US oppose the coup, American embassy personnel tried to talk Honduran military officials out of it.) During her 2012 campaign, Stein consistently claimed that the 2009 stimulus plan “was mostly tax breaks for the wealthy.” The truth is that tax breaks accounted for 38 percent of the plan, a majority of them targeted toward low- and middle-income households. That’s not criticism from the left; it’s a dishonest, scorched-earth campaign against the only party that can keep Republicans out of the White House. (And if you think that Stein wouldn’t have attacked Bernie Sanders with the same vigor if he were the nominee, then it’s a safe bet you’ve never attended a Green Party meeting. Remember that the Greens ran candidates against Ralph Nader in both 2004 and ’08.)

Two disastrous wars and a few Wall Street–precipitated recessions have helped push the Democratic Party leftward. Demographic changes in the electorate have made it less reliant on courting white swing voters. But the shift in the party was in large part a result of tireless work by the Democrats’ own base, passionate progressives who pushed the party to change.

Many Greens think that their vote isn’t wasted because it sends a powerful “message” to Washington. But why would anyone in power pay attention to the 0.36 percent of the popular vote that Jill Stein won in 2012, when 42 percent of eligible voters just stayed home? Political parties are merely vessels. The Green Party provides a forum to demonstrate ideological purity and contempt for “the system.” But the Democratic Party is a center of real power in this country. For all its flaws, and for all the work still to be done, it offers a viable means of advancing progressive goals. One can’t say the same of the perpetually dysfunctional and often self-marginalizing Greens.

For a different view on voting for the Green Party this November, read Kshama Sawant here.

Joshua HollandTwitterJoshua Holland is a contributor to The Nation. He’s also the host of Politics and Reality Radio.