Art is Disagreement

A Complete Unknown and the myths of Bob Dylan

What Do We Want From Bob Dylan’s Story?

In James Mangold’s film A Complete Unknown, we get a cautious and reverent story of a musician who has always sought to transcend the limits imposed upon him.

I’ll admit it straight off: I don’t know how to write about Bob Dylan. It’s like being asked to write about the smell of your childhood home. Every awful, beautiful memory; every fear, desire, and promise; every premonition and uncertainty—it’s all there: the origin, the prototype, the coordinates of your future feeling. It’s hard to describe something like that.

What I mean is, I really love Bob Dylan. I always have. He’s my favorite musician in a big, dumb, jealous, childish way: a love that is unknowing and primitive. And so I’m always a bit suspicious of the impulse, in myself and others, to figure out what exactly is going on there, to break him down, to make him manageable and coherent. Reading books and watching movies and listening to podcasts about Dylan—which I do, all the time—can feel a bit like going to the store, finding one of those scents from childhood emanating from a bottle of laundry detergent or hand soap, and reading out the ingredients on the back: sodium lauryl sulfate. Propylene glycol. Fluorescent brightener 71. What’s this got to do with anything? Weren’t we talking about my mother?

James Mangold’s new Dylan biopic, A Complete Unknown, provokes a similar reaction. The film, which stars Hollywood wonder waif Timothée Chalamet, is suffused with unspecific nostalgia. It reminds you of everything, and yet its ingredients are still a bit of puzzle.

This makes for a film you might want to see as Dylan devotee, but one that is also unsatisfying in a lot of other ways. “Art is a disagreement,” Dylan writes in his most recent book, The Philosophy of Modern Song. “Money is an agreement.” A Complete Unknown, it must be said, is a highly agreeable movie. The sets and costumes are period-appropriate; the lighting is cozy; the performances are plausible. Ed Norton is especially good as Pete Seeger, a kindly oedipal uncle and the folk guru whom Bob must disappoint (if not quite destroy) to complete his becoming. The music, which Chalamet performs competently, feels like an imperfect compromise between verisimilitude—it’s really Timmy singing up there!—and the necessity of displaying Dylan’s artistry. It lands in an ersatz, uncanny place, but it’s not unpleasant.

The story of A Complete Unknown is a familiar one. In brief: Baby-faced Bob arrives in Greenwich Village, guitar in hand, lies to every pretty girl he meets, and takes over the folk scene with the force of his personality, his soulful harp work, and his ability to write new songs that sound as tender, urgent, and otherworldly as the traditional ones everyone else was playing. Soon our Midwestern parvenu falls for an activist painter (Elle Fanning) and for the great Joan Baez (Monica Barbaro). He gets signed by Columbia, becomes a celebrity, and then betrays his girlfriends, fans, and mentors by “going electric”—that is, by embracing rock over folk, transgression over leftist piety, and his own ungovernable artistic impulses over tradition, loyalty, or constancy. (Recall: Art is a disagreement.)

But part of the problem is that, unlike Dylan, Mangold’s film (cowritten by Jay Cocks and based on Elijah Wald’s 2015 book Dylan Goes Electric!) is faithful, reverent, and careful with its material. The story unfolds mechanically, like a Disney ride on rails. All your favorite characters are here, in realistic facsimile: There’s Dave Van Ronk! Here comes Johnny Cash! That’s Alan Lomax! That’s Bob Neuwirth! (Greenwich Village is a small world after all….) Not everyone is going to catch or care about the moment when Al Kooper (played here by Charlie Tahan), then a 21-year-old guitar player, talks his way into the recording session for Like a Rolling Stone and starts plunking chords on an organ. But real heads know.

Perhaps the movie is less like a Disney ride and more like that other lucrative Disney amusement: the superhero movie. One need not catch every reference to follow the film; but for fans of the Dylan Extended Universe, there are Easter eggs galore! When Bob buys an Acme whistle on the street several scenes before recording “Highway 61 Revisited,” Dylan nerds are supposed to relish the moment—there it is! The whistle! Just like on the record!—as if we’re watching Thor brandish his hammer or Captain America his shield. (This is perhaps no coincidence, given that Mangold has directed several X-Men films.)

Opinions may differ, but I don’t enjoy being infantilized in this way. “Fan service” is a sickening, adolescent ordeal. If a film aspires to be art, it cannot possibly succeed through flattery—i.e., by showing us stuff we already know. “That’s the problem with a lot of things these days,” Dylan grouses in The Philosophy of Modern Song. “Everything is too full now; we are spoon-fed everything. All songs are about one thing and one thing specifically, there is no shading, no nuance, no mystery. Perhaps this is why music is not a place where people put their dreams at the moment; dreams suffocate in these airless environs.” The old man is right. And the same can be said for movies.

More from Books & the Arts

A Complete Unknown does manage some nuance and shading in its depiction of Dylan’s romantic life. Chalamet is most believable as an infuriating lover boy—needy, flighty, and affected. (See also his turn as the self-serious dirtbag boyfriend in Lady Bird.) Chalamet has chemistry with both of the film’s female leads. Barbaro is alluring and sarcastic as Baez; Fanning, sincere and wounded as Sylvie Russo (a stand-in for Dylan’s first New York girlfriend, Suze Rotolo).

In matters of love, Dylan has always struck me as a familiar masculine type: He likes being taken, but resents being had. (“I am homeless, come and take me….”) Something of the same dynamic has played out between Dylan and his audience. In Chronicles, Dylan describes being infuriated when Ronnie Gilbert introduced him at the Newport Folk Festival by saying, “And here he is…take him, you know him, he’s yours.” (Bob: “What a crazy thing to say! Screw that.”) Being tied down, cornered, stuck: These are Dylan’s primordial fears. (“I didn’t belong to anybody then or now.”) Of course, there’s irony in this: Fame is a recipe for being hounded and used. Thus Dylan’s affinity for evasive maneuvers. When we get too close, when we think we have him, can claim him, he reacts: He throws us off his trail. He goes electric. (“Strike another match, go start anew….”)

Another way of saying “Art is a disagreement” is to say that art is about making choices. Whatever else is true, Dylan is an artist who has constantly made choices, often disagreeable ones. The idea of “going electric” captivates us because it succinctly exemplifies this impulse: to risk antagonizing one’s audience (or to do so deliberately) in pursuit of one’s artistic vision. Yes, it’s a cliché, but it’s not a cliché that applies to all that many pop stars today. And the thing is, Dylan didn’t stop going electric. In the five years after Mangold’s film ends (1965), he went electric again by going acoustic on John Wesley Harding, by going country on Nashville Skyline, by going schizoid on Self Portrait. At the end of the ’70s, he went electric by becoming a born-again Christian and recording three albums of gospel songs.

Mangold seems to understand this about Dylan, but A Complete Unknown doesn’t take any similar risks. After enduring the “airless environs” of Mangold’s dutiful film, it was refreshing to rewatch Todd Haynes’s 2007 I’m Not There, in which six actors depict different aspects of Dylan’s persona. The film is full of absolutely bewildering choices, and it succeeds for this reason. You won’t miss Chalamet while watching Cate Blanchett as drug-addled, mid-1960s “mod” Bob. It doesn’t hurt either that Haynes’s soundtrack is full of Dylan covers by actual musicians, plus several tracks sung by—get this—Bob Dylan.

If A Complete Unknown largely reiterates the Dylan myth, however, that is likely to please the man himself. Dylan has always had a great reverence for myths and very little respect for myth-puncturers (i.e., the press). “People make up their past, Sylvie!” Chalamet roars in one scene. “They remember what they want. They forget the rest.”

There’s an interesting passage in The Philosophy of Modern Song when Dylan writes about Johnny Cash’s “Big River,” which he prefers to “the august solemnity of the murder ballads, hardscrabble tales and Trent Reznor covers that his fans came to expect.” Dylan doesn’t like his Johnny Cash enfeebled, hurt, or vulnerable—as Cash appears on his final, Rick Rubin–produced records. “He could climb across rivers,” Dylan writes. “He could lay track and take down greenhorns. He’s a teller of tall tales—parts the clouds and drinks nitro. This is the real Johnny Cash, and ‘Big River’ is his theme song.” For Dylan, Johnny Cash was every bit as big as he claimed to be; the myth was the man.

Boyd Holbrook’s performance as Cash in A Complete Unknown is delightful precisely because he is all cartoonish swagger and sexual charisma; he’s larger than life. Dylan, for his part, has been too many things for any one of his myths to be true—which is why Haynes split him into six. The one constant for Dylan is motion. In Chronicles, he recalls his grandmother telling him, “Happiness isn’t on the road to anything. Happiness is the road.” Ironically, she probably meant something like “Appreciate what you have.” Dylan took it to mean: Go. As he writes in The Philosophy of Modern Song, “The thing about being on the road is that you’re not bogged down by anything. Not even bad news. You give pleasure to other people and you keep your grief to yourself.” As depicted in A Complete Unknown, young Bob resented his audience (and his lovers) for trying to own him. But I wonder if that’s still true for mature Bob—or if he hasn’t found a certain comfort in constancy. Touring all the time—which he does, to this day—is an odd way to evade your public.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →One of the most beautiful songs on Dylan’s 2020 record Rough and Rowdy Ways, is called “I’ve Made Up My Mind to Give Myself to You.” On the album, it reads as a touching love song, one of his best. But when he sings it live, another meaning is impossible to miss. At last: He’s ours. The truth is, we don’t need James Mangold to give us Bob Dylan; he has done so himself.

Support independent journalism that exposes oligarchs and profiteers

Donald Trump’s cruel and chaotic second term is just getting started. In his first month back in office, Trump and his lackey Elon Musk (or is it the other way around?) have proven that nothing is safe from sacrifice at the altar of unchecked power and riches.

Only robust independent journalism can cut through the noise and offer clear-eyed reporting and analysis based on principle and conscience. That’s what The Nation has done for 160 years and that’s what we’re doing now.

Our independent journalism doesn’t allow injustice to go unnoticed or unchallenged—nor will we abandon hope for a better world. Our writers, editors, and fact-checkers are working relentlessly to keep you informed and empowered when so much of the media fails to do so out of credulity, fear, or fealty.

The Nation has seen unprecedented times before. We draw strength and guidance from our history of principled progressive journalism in times of crisis, and we are committed to continuing this legacy today.

We’re aiming to raise $25,000 during our Spring Fundraising Campaign to ensure that we have the resources to expose the oligarchs and profiteers attempting to loot our republic. Stand for bold independent journalism and donate to support The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editorial Director and Publisher, The Nation

More from The Nation

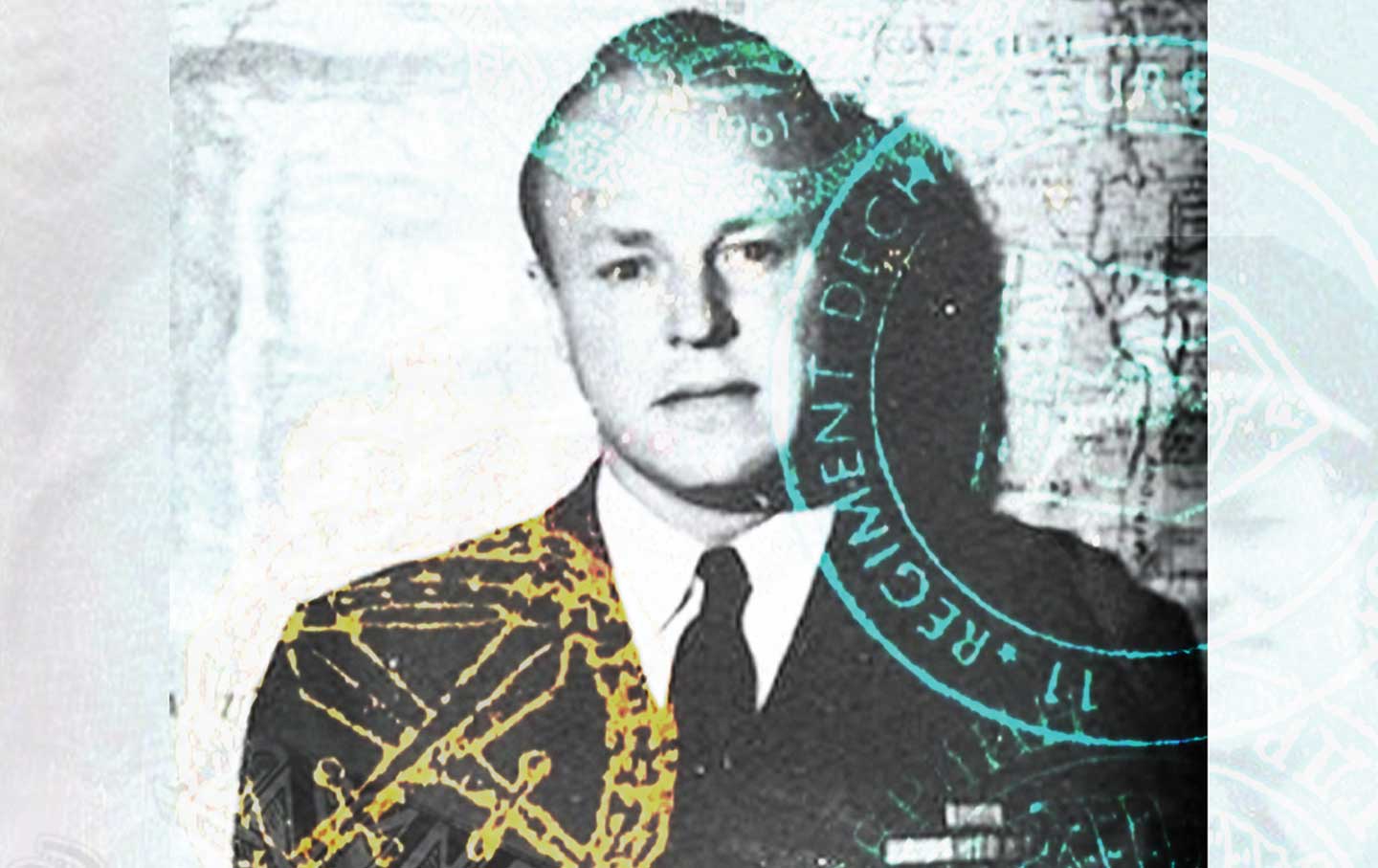

The Making of a Cold War Spy The Making of a Cold War Spy

The life and work of Frank Wisner, one of the CIA’s founding officers, offers us a portrait of American intelligence’s excesses.

The Workplace Nightmares of “Severance” The Workplace Nightmares of “Severance”

The appeal of the Apple TV+ series is how it dramatizes our alienation from labor.

How Atlanta Became a Walkable City How Atlanta Became a Walkable City

The Beltline and Georgia's experiment in pedestrian spaces.

The B-Sides of the “Golden Record,” Track Eleven: “How Will You Begin?” The B-Sides of the “Golden Record,” Track Eleven: “How Will You Begin?”