The “Cascade of Errors” That Led to America’s War on Terror

Steve Coll’s new book looks at the hubris and delusions of American foreign-policy makers and counterparts in the Middle East that led to a war that still haunts the globe.

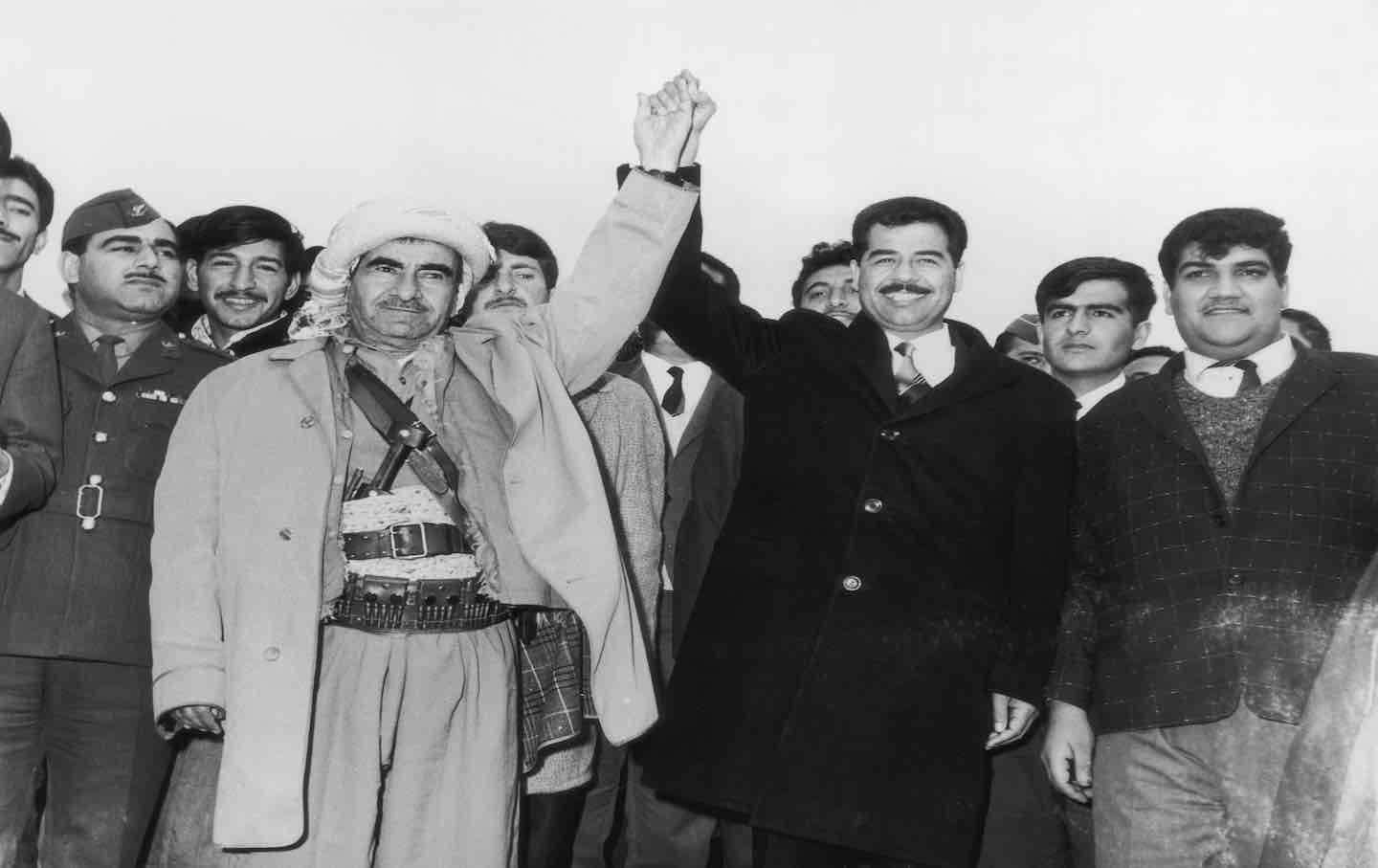

Saddam Hussein and Mulla Mustafa al-Barzani, 1970.

(Photo by Central Press / Getty Images)

In February of 1990, Saddam Hussein issued a warning to his peers in the Middle East and North Africa. The Cold War was over, the Berlin Wall had fallen, and a new world order was going to change the way diplomacy was done. “It has become clear to everyone,” Hussein said, “that the United States has emerged in a superior position in international politics.”

Books in review

The Achilles Trap: Saddam Hussein, the C.I.A., and the Origins of America’s Invasion of Iraq

Buy this bookThe venue was the second annual summit of the Arab Cooperation Council in Amman, Jordan, and the Iraqi president was hopeful that his audience would heed his message. Hussein was certain that new actors would push back against US supremacy, but in the meantime the United States “will continue to depart from the restrictions that govern the rest of the world…until new forces of balance are formed.”

Thus, it was the responsibility of regional powers like Iraq, Jordan, Egypt, and the Gulf states to form a unified front: The United States’ resource interests and imperial designs, supported by its ally Israel, had to be resisted. If they stood up to the US together rather than on their own, then they would “see how Satan will grow weaker.” As if anticipating doubts, Hussein insisted that their enemy had already “displayed signs of fatigue, frustration, and hesitation.” He had the 1983 Marine barracks bombing in Beirut in mind: The “superpower departed Lebanon immediately when some Marines were killed.”

Hussein went on, “All strong men have their Achilles’ heel.”

This scene inspired the title of journalist Steve Coll’s new and timely prehistory of the Iraq War and the War on Terror, The Achilles Trap: Saddam Hussein, the C.I.A., and the Origins of America’s Invasion of Iraq. In the wake of the Iraqi leader’s short-lived occupation of Kuwait and the ensuing Gulf War, the Central Intelligence Agency designated DB ACHILLES as the cryptonym for its covert regime-change program. Coll does not spell out the precise meaning of this counterpoint, leaving it to others to make sense of its ambiguity. But what we can make of this fatal irony is that, in the end, both Hussein and his US counterparts may have fallen victim to a like-minded hubris.

What Coll makes certain to do is to walk his readers through a magisterial, 500-page “cascade of errors.” The book begins with the CIA’s suspected involvement in Iraq’s 1963 coup, a takeover by the same anti-communist (but nominally socialist) Baathist party that Hussein would later seize and duly purge in 1979. Coll doesn’t call this a mistake per se, but his portrait of the notorious ruler’s journey from rural Tikriti brawler to the man whom George H.W. Bush christened the next “Hitler” suggests a guiding (albeit misguided) hand. And that hand was Washington’s.

Much of the first third of the book fleshes out Hussein’s litany of horrors throughout the 1980s, from his initial purge of the party (his “arrival to the Middle East’s Game of Thrones”) to his widespread use of chemical weapons during the Iran-Iraq War to the lethal gassing of thousands of Kurds in Halabja in 1988. The latter was executed by Hussein’s henchman, Ali Hassan al-Majid, remembered thereafter as “Chemical Ali.” And Halabja was part of the wider counterinsurgent Anfal (“Spoils of War”) campaign that would end up claiming 50,000 to 100,000 Kurdish lives.

Coll finds no direct link between Anfal and CIA intelligence-sharing, and the evidence suggests that Langley went out of its way to ensure no such connection. The same can’t be said for the regular deployment of chemical attacks against the Iranians, however, where the United States knowingly fed Baghdad satellite imagery used for the targeting and planning of such war crimes. Foreign policy elites like former national security adviser Henry Kissinger and then-current adviser Robert McFarlane were enthralled by the idea of keeping both Iraq and Iran bogged down in a war of attrition that would prevent either from antagonizing US allies in the region. If this meant cutting a few moral or legal corners here and there, so be it. Coll, not given to editorializing, can’t help but call this a “dark and cynical chapter in American policymaking.”

To add insult to injury, the Reagan administration armed Iran during this same period, in what has become memorialized as the Iran-contra affair. The episode in fact amounted to a parade of scandals, whereby rogue, often competing factions in the US government maneuvered in secret to achieve a grab bag of jumbled ends. This included the illegal trade of anti-tank and surface-to-air missiles to Tehran for the release of American hostages by Hezbollah; the equally illegal redirection of the resultant profits to the anti-Sandinista contras in Nicaragua; the quixotic attempt at a rapprochement with Iranian reformists who certain Reaganites hoped could minimize Soviet influence; and National Security Council staffer Oliver North’s flirtation with a US-Iran alliance against Hussein.

Such brazen scheming helped fuel the Iraqi president’s already elaborate suspicions about the United States, Iran, and most of all Israel, especially since Tel Aviv had played a central role in shipping the weapons to Khomeini’s forces. (Never mind the Israeli air strike on Iraq’s Osirak nuclear reactor in 1981.) The Baathist ruler’s antisemitism ran deep, and any partnership of convenience with the world’s hegemon always would have contended with the United States’ historic bond with the Jewish state.

Even as tensions mounted, the US government was keen to protect Hussein as long as he waged a war that was favorable to the White House’s interests. Reagan successfully lobbied against a specific iteration of the Prevention of Genocide Act (1988) that would have sanctioned the dictator for his mass extermination campaign against the Kurds. Later, when George H.W. Bush took office, he and most of the US business community were eager to restart the oil-rich development bonanzas that had characterized European-Iraqi relations in the 1970s, from generous technology transfers to broader foreign investments in industry, science, transportation, and communications. The foreign policy establishment even conveyed an interest in bringing Hussein into the fold of the ongoing Palestinian-Israeli peace process during the earliest years of Bush’s administration.

Yet none of this stopped Hussein from assuming the worst on the part of his Western suitors—and preparing for it.

Coll leaves the impression that things might have gone differently had the Iran-contra affair never happened. “In foreign affairs,” he writes, “[Hussein] referred regularly to the Iran-contra revelations of 1986 and their seeming proof of an ongoing conspiracy against him by the United States, Israel, and Iran.” Although more muted, Coll also compels his reader to imagine an alternative history that perhaps didn’t entail a pointless war with Iran and the hundreds of thousands of deaths that followed, or a wracked and debt-ridden Iraqi economy and dysfunctional society. There is, he imagines, a counterfactual scenario in which Hussein may have never felt the need to issue his call for an Arab front against the American “Satan.” That speech marked the beginning of the end: It jump-started his regime’s WMD brinkmanship; its invasion of Kuwait, its exacting creditor neighbor; its subsequent crackdown on Iraq’s Shiites and Kurds; and the cavalcade of failed CIA-backed coups and sanctions that followed, culminating in George W. Bush’s pyrrhic coup de grâce in 2003.

Given Hussein’s destructive predilections, that’s a tough ask. It also says nothing of the actions of Khomeini’s Iran, and how the aggressions of the two ruling classes may have goaded each other with or without US encouragement. And Coll himself doesn’t appear sure that the profitable peace and development of the 1970s could have lasted all that long anyway. Hussein’s overall combativeness and specific animosities toward Israel and the United States were “unalterable,” and “perhaps the catastrophic turning point of the Kuwait invasion was unavoidable, given Saddam’s secrecy and appetite for the emirate’s wealth.”

At times, Coll seems to retreat to more modest proposals. He surmises that clearer US redlines in the lead-up to Iraq’s seizure of Kuwait might have prevented the invasion. Or that Hussein’s gestures in the latter half of 1993 to make amends with the West ought to have been heeded. Had Bill Clinton ignored congressional hawks and taken up the Iraqi leader’s attempt at rapprochement, it is possible the Democratic president could have cut off the bipartisan momentum toward the Iraq Liberation Act in 1998—the law that made Hussein’s removal official US policy—and its most catastrophic realization five years later. Maybe Hussein really could have joined the United States in national or regional infrastructure projects, the containment of purported terrorist threats, and even—as Hussein surprisingly recommended—the furtherance of the Oslo Accords. And in doing so, maybe US and European intelligence could have arrived at the accurate conclusion that Hussein had destroyed his WMD program in 1991 and never looked back.

Still, The Achilles Trap’s virtues don’t derive so much from its counterfactuals as its ironies. Saddam Hussein lecturing the Arab world about strong men having their Achilles’ heel is ironic. So is the United States naming its covert regime-change program DB ACHILLES. What’s even more ironic is their juxtaposition. In the age of the Internet meme, one is hard-pressed not to think of the two Spider-Men pointing fingers at each other.

When Hussein noted in 1990 that the United States was showing signs of fatigue, frustration, and hesitation, he was projecting. But he was also, ironically, telling a truth: What might have felt at the time like a new dawn in American global power looks in retrospect more like the closing chapters of the superpower’s golden age.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →An identical effect is achieved when Coll quotes the Iraqi authoritarian on the eve of his ouster by Bush the Younger. “Narcissism is dangerous,” he said of the prideful US president, “and can cost a man the opportunity to be wise.” Facing his own imminent demise, wisdom of a sort bubbled up. “The American hand that carries the weapons and the stick while dealing with the world today will weaken in two years, five years, fifteen years, or twenty years,” Hussein told India’s oil minister during a routine diplomatic rendezvous. “And it has started to happen now.”

The Iraqi tyrant derided America’s phony electoral rituals and deep state. He shrewdly predicted that the post–Cold War superpower would prove “incapable of satisfying its obligations,” specifically in Eastern Europe, where it promised too much. While his belief that Iraqis would rise up on his behalf was absurd, Hussein was correct that an Iraqi resistance would prevail in causing havoc for the country’s occupiers, eventually running them out.

Even Hussein’s waning moments in charge come with an ironic kick. Right before going underground, he rushed to press his final novel (Hussein was a prolifically terrible novelist), Get Out, You Damned One!, in which the breathless, last-ditch apologetics for his decades-long reign hold up an unsettling reflection to the American-exceptionalist hysterics that make up so much of The Atlantic or the New York Times op-ed page and the everyday rantings of television broadcasters. Hussein’s allegory is set in ancient Babylon and centers on two brothers meant to represent Judaism and Islam. The Jewish sibling is a sex pest, an inveterate war profiteer, and a client of the Roman Empire, and the Muslim brother must lead a successful resistance against such stand-ins for Israel and the United States. Despite ensuring that his literary last hurrah sold 40,000 copies, Hussein’s hope that it might inspire his countrymen to remember him fondly—let alone make him an icon of future resistance—was never realized. He was executed in December of 2006, and without many living adherents in Iraq to show for it.

Political life in the United States can’t be equated with Saddam Hussein’s Iraq. The US intelligentsia, for one, is heterogenous and enjoys liberal democratic protections. Respectable opinion in Washington or New York nonetheless has a habit of mirroring Hussein’s most febrile fantasies. Metropolitan elites style themselves as grand protectors, even as they enact or enable calamitous violence. They deny the vast harms that their military-industrial behemoth unleashes upon millions, just as they exaggerate their capacity to deliver peace and prosperity: In the US support of Israel’s war in Gaza—a war purported to protect the Jewish people through the extermination or dispossession of their Palestinian neighbors—we see a twisted reflection of Hussein’s own prejudices and murderous delusions. Above all, the distance between the conventional wisdom of America’s rulers and the animosities of its debased and riven public keeps growing. Another Achilles trap just might beckon from the wings.

More from The Nation

“The Pitt” and the Gritty Return of the Hospital Drama “The Pitt” and the Gritty Return of the Hospital Drama

In a frenzied medical drama, the limits and problems of the healthcare system became the basis of the show’s plot.

The Uncomfortable Genius of Mike Leigh The Uncomfortable Genius of Mike Leigh

In “Hard Truths,” Leigh reminds us that a family dinner can tell the story of a whole society.

Henri Bergson’s States of Change Henri Bergson’s States of Change

Why did one of the early 20th century’s most famous philosophers go out of fashion?

Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan’s Voice From the Past Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan’s Voice From the Past

The Pakistani qawwali icon sang words written centuries ago and died decades ago. He’s got a new album out.

The Real Problem With Trump’s Cheesy Neoclassical Building Fetish The Real Problem With Trump’s Cheesy Neoclassical Building Fetish

Sure, it’s a dog whistle for “retvrn” types and the results are tacky—but that’s not the worst part.

The Art and Automatons of Kara Walker The Art and Automatons of Kara Walker

Walker’s new installation at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art offers us visions from both the past and future.