What Adorno Can Still Teach Us

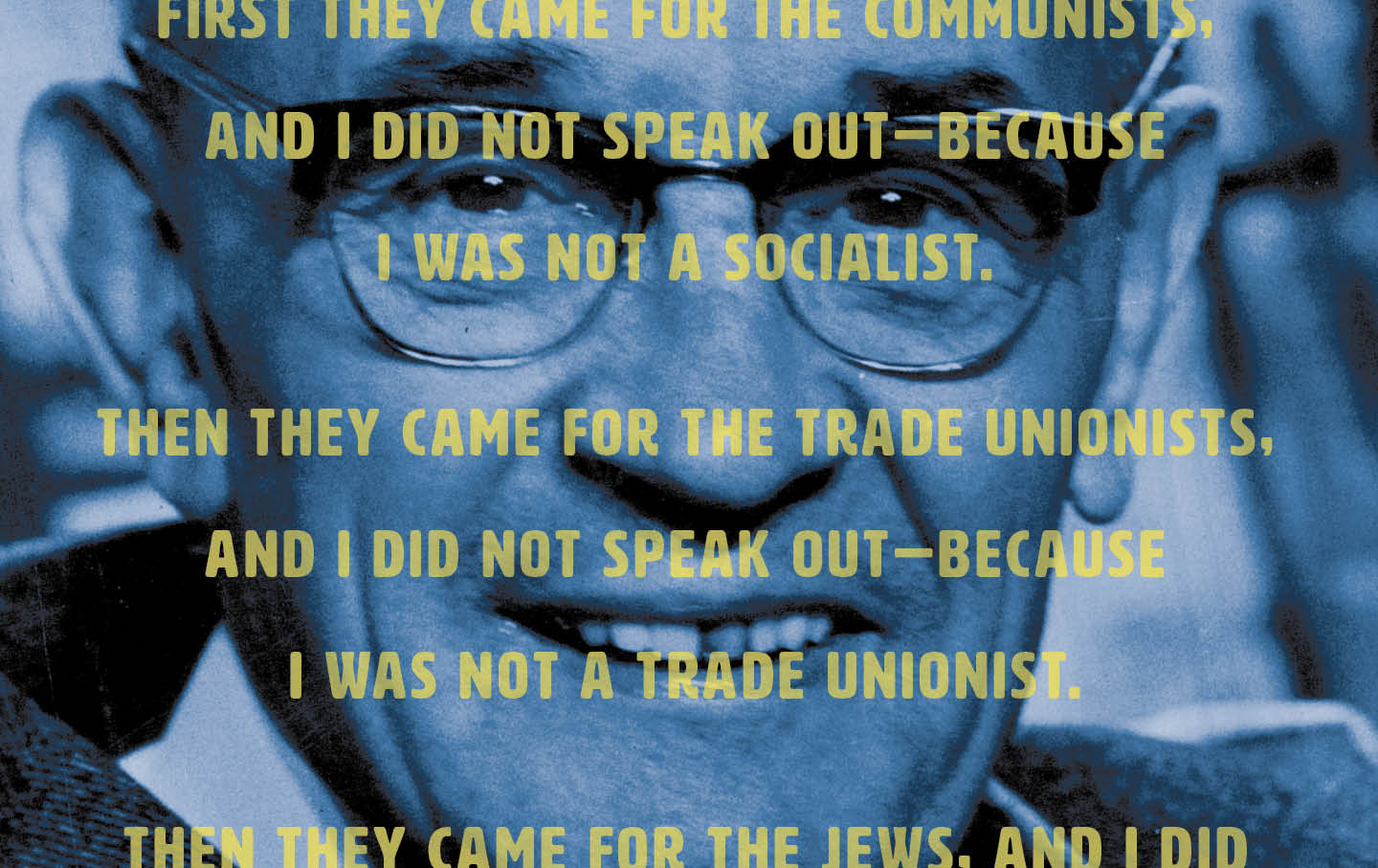

A conversation with Peter Gordon about the enduring influence of the Frankfurt School’s leader, the future of critical theory, and his recent book, A Precarious Happiness.

Few 20th-century thinkers have cultivated a reputation for pessimism like that of Theodor Adorno: His very vision of modern society, some might have you believe, is one of absolute despair. The famed leader of the Frankfurt School of critical theory once quipped, “Every image of humanity, other than the negative one, is ideology.” Yet in his book A Precarious Happiness, the Harvard intellectual historian Peter Gordon argues that readings of Adorno’s work that cast him as a thoroughgoing pessimist or skeptic are fundamentally misguided; instead, Gordon suggests, Adorno’s project is oriented toward a conception of human happiness and flourishing in a broken world. Thus, even as Adorno stresses how damaged the world is, happiness can nevertheless be pursued in it—hence the precarious nature of Adorno’s conception of the good life.

The Nation spoke with Gordon about Adorno’s conception of happiness, his thinking about jazz and classical music, his relationship with the Frankfurt School, and the future of critical theory.

—Daniel Steinmetz-Jenkins

Daniel Steinmetz-Jenkins: Few philosophers of the 20th century could match Adorno’s reputation for seeing the modern world in a totally pessimistic light. Your book argues that this view of him is wrong. But before we unpack your reasons why, can you first say something about the defining features of critical theory as developed at the Institute for Social Research—the famous school of German social theory that Adorno cofounded just over 100 years ago? And how does this relate to the standard view that portrays Adorno as merely a critic of modern societies?

Peter Gordon: The Institute for Social Research was founded in Frankfurt in 1923, and in its initial years it served chiefly as an archive for the history of the working class and contributed to the project of editing works by Marx and Engels. It only became the birthplace for what we now call “critical theory” in the early 1930s, when Max Horkheimer assumed the directorship, but it remained a collective of intellectuals, including Friedrich Pollock, Herbert Marcuse, and, of course, Theodor Adorno, among others. Critical theory was and remains a highly diverse and interdisciplinary practice that embraces both sociology and philosophy but has no dogmatic limits: It has transformed dramatically over time, and critical theory is riven with a great many disagreements, even lines of serious fracture.

It may be worthwhile clearing up one small terminological confusion: The term “critical theory” is often used today in a more capacious sense to characterize a wide variety of approaches (associated, for instance, with Nietzschean or Foucauldian genealogy, or with trends that emerged from French structuralism and post-structuralism or semiotics). But these have only a tenuous affinity with the critical theory associated with the institute in Frankfurt. I have no interest in policing intellectual boundaries, and this capacious meaning has great merit, though for the sake of precision we should try to keep the distinction in mind.

One distinguishing mark of Frankfurt School critical theory is that it has always drawn instruction from the legacy of German idealism, from Kant and Hegel, and from the materialist transformation of left Hegelianism as developed by Marx. Horkheimer once said that critical theory is guided by “the materialist content in the idealist concept of reason.” That strikes me as more or less accurate: The basic orientation of critical theory is to develop a better insight into the structural pathologies of modern society that cause pervasive suffering and block the emergence of a genuinely free and rational society. It’s a practice of rational criticism guided by an emancipatory intent. But critical theory today should not be defended as a comprehensive doctrine that remains closed to other approaches. To use a German phrase, today it is more a Denkstil (or “style of thinking”) than a settled or self-contained theory.

DSJ: You are quick to point out that aspects of the more standard interpretation of Adorno as a cynic are not wrong. Where, though, does it ultimately involve a misreading of Adorno?

PG: Adorno belonged to the “first generation” of critical theorists who fled European fascism in the 1930s. Most of them survived the war—Walter Benjamin (an affiliate of the institute who lived mostly in Paris after 1933) died tragically en route. With the passage of time, those of us who remain interested in the first generation have come to recognize the diversity of its views. Adorno continues to attract attention for his distinctive philosophical orientation, chiefly as he presented it in his late work, Negative Dialectics, which was first published in 1966, just three years before his death.

Many scholars have contributed to the interpretation of Adorno’s work, and I wouldn’t want to overstate the novelty of my claims. Adorno is too often seen as a thoroughgoing pessimist who devoted his criticism only to the task of exposing what is “negative” or irrational in modern society. The widespread caricature of Adorno as a scowling contrarian or snob continues to inhibit our understanding of his work. This caricature, I believe, does a grave injustice to the complexity of his thought. My general argument is that Adorno was far more conflicted—or, to use the more technical term, dialectical—than the standard interpretation allows. As a critical theorist, he devoted his work to exposing the negative, but with an anticipatory orientation toward the largely unrealized possibility of human flourishing.

His writing, though often dark and even ruthless in its criticism of present irrationality, is nonetheless shot through with glimpses of what happiness would be. These anticipations are admittedly uncertain, since in a damaged world we see as if through a glass darkly. But the concept of an unrealized good is already implicit in the critique of what is bad. In a rejoinder to the Hegelian notion that philosophy only has the task of painting the gray of the world in gray, Adorno once explained: “Consciousness could not even despair over what is grey if we did not possess the concept of a different color, whose scattered trace is not absent in the negative whole.”

DSJ: What, then, are the main features of what you describe as “a precarious happiness” in Adorno’s thought?

PG: The normative ideal of happiness or human flourishing has its origins in classical philosophy—in Plato, Aristotle, and the Stoics such as Seneca. In Kant, it gained a central importance in the thought that in moral reasoning, we must postulate an ultimate convergence between our virtuous conduct and our just deserts. Kant thought of this convergence as the summum bonum, or the highest good. The implication is that the demands of morality and the natural expectation for happiness do not in principle conflict. Of course, Kant believed that to conceive of this convergence, we must presuppose an afterlife. In Negative Dialectics, Adorno draws upon Kant’s reasoning but sharply rejects the inference that the highest good would lie beyond mortal life. As he explains, the essence of Kant’s philosophy is the “unthinkability of despair,” but the demand for happiness can be retained without appealing to Kant’s postulate of eternity. On the contrary, Adorno says that we can affirm the postulate of happiness if and only if “metaphysics slips into materialism.” I find this conclusion fascinating. Adorno is sufficiently realistic in his social criticism to acknowledge that we do not possess any certain or perfect conception of what our happiness would consist in. His basic view is that in a damaged world, all of our ideals are likewise damaged; this reflects his Marxist reluctance to fill out any pictures of utopia. This is why all current intimations of happiness are (in his words) “precarious” and interlaced with despair.

DSJ: Isn’t the idea of “precarious happiness” simply a theological idea? It sounds a lot like, for instance, the idea that the world is fallen and human beings are sinful, and yet there are still flickers of light and hope, as the world has been made by a benevolent God who created human beings in his image.

PG: I wouldn’t say that the concept of happiness is simply theological, or even primarily theological. The question of what a life of human flourishing might consist in has been a major preoccupation in philosophy since its inception, and it even reappears as a theme in Marxist and neo-Marxist thought—think of Marcuse’s arguments in Eros and Civilization. Granted, one occasionally comes across interpretations that wish to characterize Adorno himself as a theologian or crypto-theologian. These interpretations can be instructive: In an earlier book, I entertained the possibility of comparing Adorno’s negative dialectics with negative theology. At the end of the day, however, we should resist the suggestion that he was in any sense an essentially religious thinker. The problem with such labels is that they are one-sided.

Regarding the philosophical tradition, Adorno is a dialectical thinker. By this I mean that, much like Hegel, he both mobilizes and overcomes conceptual resources from the past. So it really shouldn’t surprise us that he is willing to invoke theological concepts when their meaning can assist him in motivating certain this-worldly or even materialist philosophical claims. The alternative would be a dismissive or supersessionist posture that would condemn the archive of past concepts as somehow irrevocably tainted—an obsolete body of thought that must be discarded altogether. As a historian of philosophy, I would find that kind of baby-with-the-bathwater attitude terribly unhelpful.

We continue to learn from past philosophies even as the world confronts us with seemingly unprecedented circumstances. I don’t know of anyone who would claim that we should stop reading Plato, for instance, simply because most of us now find his stronger metaphysical commitments implausible. Dialectical thinking in this respect might be understood as an attempt to formalize the basic structure of the human learning process: We take up experiential content, subject it to rational scrutiny, and then preserve what we can, even while transforming what we carry forward with a sense of deepened knowledge. For Adorno, this learning process commits him to a secularizing gesture that can learn from theology even while it leaves no sacred concepts immune. He summarized this view in a remark in a radio discussion (later published as “Revelation or Autonomous Reason”) from the late 1950s: “Nothing of theological content will persist without being transformed; every content will have to put itself to the test of migrating into the secular, the profane.”

DSJ: You write that readers should be prepared to admit that Adorno was not a Marxist in the doctrinal sense of that term. Yet you also state that his understanding of human flourishing was indebted to Marxist insights. Can you elaborate on this?

PG: Adorno was hardly an adherent of Marxist theory in the orthodox sense, if by this we mean a theory that ascribes a distinctive revolutionary potential to the working class and sees in class conflict the driving force in a pattern of historical transformation that concludes in a condition of universal freedom that brings history itself to an end. Adorno was far too skeptical about the technological optimism that seems to be built into orthodox Marxism, and like many of his generation, he had also lost his confidence in the proletariat as the singular and unified collective agent of history. Nor did he accept the strong element of economism that lurks in some versions of historical materialism. He worried that economism reflects an ideology of unfreedom: Rather than restoring to humanity our self-conception as agents who have the capacity to shape our own destiny, it eternalizes the experience of ourselves as mere objects who are locked in a deterministic mechanism. Vulgar Marxism, you might say, is not a solution to our unfreedom; it is merely its symptom.

Adorno was also never foolish enough to sign on to the lockstep ideologies of the Communist Party, and he saw in Soviet Marxist-Leninism a brutal form of authoritarian collectivism, a betrayal rather than a realization of Marx’s original dream.

All the same, this critique of Marxist orthodoxy hardly means that we can dismiss Adorno as a partisan of Cold War liberalism (or whatever polemical categories may come to mind). Many thoughtful people have rejected the false choice between communism and anti-communism that seems to have held so many intellectuals captive in the mid-20th century, and those of us with family from the Soviet bloc know something of the misery it brought to millions. Still, I want to argue that Adorno sustains in his philosophy a broadly materialist orientation, though I use the term “materialist” only in the most capacious sense, since he assigns the highest importance to our this-worldly experience of human flourishing and takes seriously the Marxist idea that a transformation in social arrangements would allow for nothing less than “the emancipation of the senses.”

Throughout his work, Adorno explores what it would mean for the human being to find true fulfillment in material experience in all of its manifold dimensions, from the simplest pleasures of the body to the most exalted pleasures of art. Many readers of Adorno dismiss such references to human fulfillment as marginal to his thinking or as signs that he had not succeeded in liberating himself from bourgeois standards of the good life. I think such interpretations are mistaken. Adorno remains a dialectical thinker chiefly because he does not see the social order as uniformly false or coherent. He sees it as shot through with contradiction, and, much like Marx, he discerns in current contradiction the unrealized promise of a future happiness that we are presently denied. In this respect, he exemplifies the basic practice of immanent critique: The norms that govern our present world are not self-consistent; they are simultaneously true and false, at once ideal and ideology. They exhibit an unresolved tension that can only be remedied through a thoroughgoing change in social relations that would bring about what Adorno calls our “reconciled humanity. ”

I grant that this may strike some skeptics as wildly utopian. Not unlike Marx’s own theory of society, it’s a utopianism chastened by a realistic assessment of what current conditions are like. Marx never believed that it was possible for the social critic to leap out of the present to articulate what our future condition would be. Adorno remains, at least in this respect, a faithful child of Marx: He seeks in the present the scattered traces of material possibility that we are currently denied. This is one reason why the unfulfilled norms of modernity remain precarious or even damaged. There’s an analogy here between Marx’s theory of immiseration and Adorno’s theory of anticipatory norms. Like Marx, Adorno does not believe that current conditions permit us to grasp the unblemished standards that will one day be realized. The working class is not gifted with perfection; it suffers grave distortion. We could say the same about the standards that guide us in the practice of social critique: The norms that we must invoke for the purposes of criticism are as damaged as the damaged world.

Adorno once said of his philosophy that it is not so much a system as an anti-system in which all concepts stand equally close to the center. I would nonetheless say that his philosophical commitments are animated most of all by a single principle that he calls “the primacy of the object.” This principle is materialist in the broad sense: He wishes to dismantle the idealist doctrine that the cognitive subject has the capacity to dominate the world. Much of Adorno’s philosophical work is consumed with the idea that we should resist the power of the subject; we should instead acknowledge the decisive role of the material, objective world in shaping our individual and collective experience. Adorno believed that no matter how strongly we insist on the constitutive role of our concepts, there will always remain a moment in experience that will escape our conceptual grasp. This moment is what he calls the “non-identical. ”

Although this is admittedly a controversial claim, Adorno went so far as to entertain the thought that the non-identical is a materialist analogue to what Kant called the “thing in itself.” It marks the limit point of the subject’s power and is, in this sense, a token of what the philosopher Rae Langton has called “epistemic humility.” In Marxist terms, the non-identical is that which signifies the absolutely particular or the non-fungible, the element that is resistant to the capitalist logic of exchange. One could argue that much of Adorno’s critical efforts are driven by the task of excavating moments of non-identity in all precincts of our life. These moments of non-identity have an instructive character—namely, they show us something about what the world should be like. This is what I mean when I refer to them as “sources of normativity.” In this respect, we aren’t far from the anticipatory or normative force that Marx sees in the self-contradictory or non-identical moments of capitalist society.

DSJ: One area where you point to the trace of happiness at work in Adorno’s thought concerns his thinking about aesthetic theory and experience. You state that, for Adorno, “all art has its share in truth insofar as it serves as a transcript of human suffering.” Here, your book contains a number of excursions concerning Adorno’s writings that address classical music. And yet Adorno famously reduced jazz to the commodity form, even proving tone-deaf to the human suffering and hope expressed by “Negro spirituals” and the blues. You, of course, rebuke Adorno for these views. But given them, aren’t there reasons to think that his social theory is rather limited in its ability to address the Black experience?

PG: What Adorno called “jazz” is not what we associate with that term today. He was using the word in an expansive sense as a name for the entire realm of commodified music; what he knew of the genre was confined almost exclusively to the big bands of the time, most of all Paul Whiteman and his orchestra (which was, incidentally, an all-white group). It may be challenging for readers today to allow for this difference in knowledge, but it’s hardly news that Adorno was highly critical of commodified culture; he was critical of all of the products of the culture industry. I think that part of the problem is that Americans like to imagine that our own commodified music is really a realm of expressive freedom, so when they read that Adorno didn’t like jazz, they take this as some kind of elitist reflex. But there’s a deeper misunderstanding here: The fact is that Adorno did occasionally like jazz or specimens of music from what we call the “American Songbook.” He even wrote some admiring words about at least a few examples of the genre. Unfortunately, those few words of admiration aren’t nearly as well-known as the more polemical essays that he wrote about commodified music. The deeper lesson that we should take from this controversy is that Adorno brought to culture some highly exacting standards of criticism, and he refused to exempt anything from his withering gaze. But why would we expect a critic in the neo-Marxist tradition to adopt a more charitable view? It’s a basic premise of Marxist theory that capitalist society is marked by pervasive pathologies that also manifest themselves on the level of culture.

Regarding the tradition of ostensibly “high art” music, Adorno was no less sparing in his criticism. He loathed much of it—read what he has to say about Sibelius or Stravinsky or Tchaikovsky, and it’s hard to come away with the idea that he harbored an unreflective love of an exclusively European canon. Most of his writing is confined to an even narrower stratum of musical composition in the German tradition that stretches from the first Viennese School (Mozart, Haydn, and Beethoven) to the so-called second Viennese School (Schoenberg, Webern, and Berg, who was Adorno’s own teacher in musical composition). Adorno wrote numerous studies for a never-completed book on Beethoven, and he published what I consider truly insightful books on both Wagner and Mahler. Here too, however, he was a discerning critic rather than a mere acolyte. What he admires in an artwork is not its illusory transcendence but its capacity to transcribe in its very form the suffering and imperfection of the surrounding world. This is why he was especially drawn to the later works by Beethoven, in which the breaks and fissures seem to express the subject’s limitations and the promises of non-identity. Still, we shouldn’t conclude that Adorno was especially drawn to music that was as damaged as the damaged world. Invoking a famous idea from Stendhal and Baudelaire, he said that all genuine art also serves as a “promise of happiness.” Incidentally, this is where I found the title of my book. Adorno once said of modern music that it contains as much “precarious happiness” as it does despair. To me, this line conveys his broader understanding of art as an unresolved dialectic.

DSJ: Such an issue, of course, relates to more general questions about the relevance of Frankfurt School critical theory to the present moment. As mentioned earlier, this school of thought celebrated its 100th anniversary last year. Some might wonder about its relevance for today—does it have much to say about neoliberalism, forever wars, etc.—or who the current generation of Frankfurt School–inspired scholars even are. Is this a school of thought that is now in crisis?

PG: I find the very idea of “relevance” rather distasteful. One of the worst things one can do with any body of theory is to hold it up to the problems of our present time and conclude that if the theory doesn’t furnish a wholly satisfactory response to all of them, it should be discarded as obsolete. I know that there’s a vogue for this dismissive gesture among intellectual historians. But in my opinion, this is a historicist conceit that we should resist. It reminds me of some of the more skeptical literature about Marxism, in which we are told that Marx was a thinker of the 19th century whose concerns are no longer relevant to the current age. All theories provide us with insights that are partial or incomplete, and no single theory is an all-purpose bromide for everything that ails us. If we are looking for comprehensive doctrines, we might have better luck if we turned to religion (and, I would add, it was a typical charge during the Cold War that Marxism itself was little more than a secular religion because it was non-falsifiable and offered an answer to everything). Once we accept that no one theory can serve as our skeleton key for unlocking all of the problems we confront, we are better positioned to think with freedom and spontaneity without feeling ourselves tethered forever to one doctrine.

One advantage about critical theory today is that it’s not a self-enclosed school—the very idea of a Frankfurt “school” is misleading. It’s more an attitude: It sustains our openness to contradiction and modifies our insights as we go. The idea of a learning process that responds to new circumstances is built into the theory itself. By the way, the current director of the institute in Frankfurt is Stephan Lessenich, a sociologist, and he is bringing to the institute a renewed emphasis on empirical research. Now it’s fairly obvious that Adorno himself had little talent for thinking in detail about formal questions of politics or economics; his strengths lay elsewhere. To ponder questions of that type, one would want to read Kirchheimer, Pollock, Neumann, and so forth. They, too, were members of the first generation of critical theorists, but I still wouldn’t expect them (or any theorist) to furnish answers to all of the problems that may preoccupy us today. So I would resist the suggestion that critical theory is in crisis; that sounds a tad overdramatic. On the other hand, I often fear that critical thinking as such is now in jeopardy. Manifold trends in modern society (economic, structural, and cultural) are closing up the spaces in which genuine critique can thrive. Much of what passes for intellectual conversation these days strikes me as excessively combative and theatricalized—a strategic game of wits rather than careful reflection.