Examined Lives

Agnes Callard and the politics of public philosophy.

Agnes Callard and the Examined Life

In her new book, Callard makes the case that we should all live more philosophically but where does politics fit in?

Agnes Callard’s Open Socrates is like many works of philosophy: It is addressed to a certain kind of skeptic. Most philosophical works are addressed to skeptics, but they tend to be philosophical skeptics—the metaphysician who doesn’t find arguments for the existence of the external world convincing, the philosopher of knowledge who isn’t quite sure our hunches count as “knowledge,” the moral philosopher who hears talk of “normativity” and can’t shake the mental image of a cop barking orders ultimately backed by violence rather than deep moral truth. Those skeptics are, at bottom, in on it: They are moved and movable by philosophical argument, or so we imagine.

Callard’s book is addressed to a different kind of skeptic: the one skeptical of the philosophical life. As she writes in the introduction, even academic philosophers often separate the rest of their own lives from their philosophical inquiry and give anodyne and bloodless justifications, such as the development of “critical thinking skills,” when pressed about the discipline’s value. This evasion amounts to the conviction for many of us that we are already intellectual enough about how we live our lives and that we shouldn’t “overdo it” when it comes to living reflectively. Callard wants to make the case for taking a different path, for the examined life: a life of courage and curiosity that is modeled, she argues, after Socrates and his approach to relentless questioning and open-ended philosophical conversations.

On the whole, I find myself conflicted about the case that Callard makes for the examined life. As a philosopher who aspires to something I’d readily describe as living philosophically, I am more than sympathetic to the book’s overall project. In an era when both AI chatbots and garden-variety plagiarism threaten to replace learning and instruction, a book advising people to get comfortable with thinking for themselves is a genuinely timely contribution, especially for those who are less fixated on philosophy—even on the off chance that ChatGPT or DeepSeek will provide a suitable summary of Open Socrates’ contents. But Callard does not simply aim to convince us that we should live philosophically in general. She insists that we embrace the Socratic model for doing so: that we confront even the most intimate aspects of our days, such as our romantic lives and our eventual deaths, with the same unsparing examination that Socrates subjected his conversation partners to.

In this way, Open Socrates largely delivers on its first promise: It inspires us to live more philosophically; it pushes us to think about how to live a life defined by actual principles that we reflectively endorse and not simply the most expedient rationalizations that occur to us in any given situation. But Callard undermines this valuable point by describing the examined life and the ideas it might produce strictly in terms of conversational roles, underemphasizing the social roles and political hierarchies that determine who we are and allow us to have open-ended philosophical conversations in the first place.

Callard begins Open Socrates not with Socrates himself but with a reason we might need him: what she calls the Tolstoy Problem. Every day, we are faced with a choice: either to think about and justify everything that we do or to simply abandon all of that thinking and go about our lives. Often, Callard argues, we settle for a false sense of urgency—“I ‘must’ go to the store, I ‘have to’ get to work”—to get ourselves moving, because we fear that if we asked a few too many “why” questions, we might not find any answers. Socrates offered a different way out of this quandary by insisting that instead of abandoning justifications altogether, we spend more time thinking and talking about them—testing propositions, questioning prior assumptions, and working toward a new set of principles.

The Tolstoy Problem, Callard continues, is named after the famous Russian novelist Leo Tolstoy. A man of noble heritage and thoughtful rigor, Tolstoy did not have much urgent or necessary work to do in order to make a living, and so he had a lot of time to spend thinking about such “untimely questions” as why he should look after his estate, or seek to protect his existing wealth, or attempt to increase his literary fame, or do any of the other things that until then had made up his life. Yet despite devoting considerable thought to these questions, he was often unable to come up with answers. The resulting depression made Tolstoy suicidal. What he decided to do about this, however, Callard views as a form of surrender: He concluded that some questions are simply unanswerable—in fact, that they are not even worth asking. And so he gave up his quest, stopped vacillating between actions, and just started to live.

For Callard, this was a cop-out, because Tolstoy had arrived at something profound and then backed away from it: the realization that to live an examined life is neither simple nor easy, and that there are no quick answers. Callard likens a life lived the Tolstoy way to living 15 minutes at a time: We move from room to room, situation to situation, doing whatever seems right at the time, unburdened and ungoverned by any deep principles or commitments or even an attempt to find some. The principle or rule we followed in the last 15 minutes may exist in tension with or even totally contradict the one we apply in the next 15 minutes. This represents a kind of incoherence and even, perhaps, a self-betrayal that Callard calls “wavering.” A wavering life, informed by positions held lightly and transiently, doesn’t add up to a coherent life lived on purpose—the kind of life that Socrates lived.

So what is so special about Socrates’ way of going about life? For Callard, the way to escape the depression that comes from struggling to answer the question of action and meaning in everyday life is to embrace the challenge it poses, to do what Socrates did: view the struggle—view the very act of philosophy itself—as a kind of conversation.

Perhaps for exactly this reason, the works of Plato, which provide us with the most compelling portrait of Socrates in action, were written as dialogues—mirroring the commitment of the historical Socrates to philosophical conversation as the proper approach to philosophy, as opposed to the atomized thinking of the individual in the proverbial armchair. But no matter the reason for Plato’s chosen form, this Socratic method is found everywhere in the dialogues.

Callard acts as our guide through these texts, including the Protagoras and the Meno, offering close readings in which she presents us with a set of novel interpretations of Socrates’ personality and character and what his famous method entailed. Callard argues that above all else, Socrates was a “gadfly,” but not merely because he was enamored with argument; instead, it was because he had a distinct view of philosophical progress.

In the dialogues, philosophical conversation involves a sort of role-play, with one person acting as the “theory builder,” who tries to establish the truth of some idea, and the other acting as the “refuter,” who tries to tear the idea down. This resolves an apparent paradox between the dueling commitments of good inquiry: seeking out truth (and thus being somewhat confident that you’ve found it) and avoiding falsehood (and thus being skeptical that you’re in possession of the truth after all).

Understood this way, the Socratic method divides labor between people by assigning them different roles. If this is necessary to make meaningful intellectual progress, it would explain both why conversation is important for philosophy and why it is so central to the examined life.

Callard’s successes in the early parts of Open Socrates are also emblematic of the book’s shortcomings in the later ones. She is rightfully attuned to the importance of philosophical conversation. Her discussion of “wavering” is genuinely illuminating in a way that makes a real intellectual contribution to ongoing philosophical discussions about those sneaky biases in personal moral judgment. While other philosophers might explain the actions that people take, even if those actions betray the principles they claim to have, as a “weakness of will,” Callard calls into question whether people live their lives in a way that’s compatible with having principles in the first place—whether seeking coherence across time turns out to be just one possible way to live.

But Callard’s focus on philosophical conversation can at times become a strategy of evasion—a means of avoiding some of the untimely questions concerning the examined life that she might not want to answer. The very first line of Open Socrates admonishes the reader, “There is a question you are avoiding.” For Callard, that question is: Why are you living this way? But this only points to a host of questions that Callard herself avoids. Why a person lives the way they do is not explained solely by the principles they have or the conversations in which they developed them, but also—and perhaps chiefly—by the world in which they find themselves.

This use of conversation as an avoidance mechanism becomes most evident in Callard’s two chapters on politics. In the first, on justice and liberty, she begins with a curious tale about a mistake on her naturalization papers to become a US citizen: Her gender was listed as male. Callard isn’t sure how this error occurred but speculates that it might be related to the fact that her and her parents’ native language, Hungarian, doesn’t have gendered pronouns. But either way her father refused to correct her papers because he wouldn’t risk temporarily giving up the original legal documents that had established her as a US citizen.

For Callard, this amusing tale of a bureaucratic mistake leads to a more serious set of questions. The point of her story, we are told, is not to show us the arbitrary ways in which our immigration system shapes people’s lives. Nor is it to demonstrate the differences among linguistic structures, or the social importance of gender, or how any or all of these things bear on the concept of freedom and the questions of justice and equality. Instead, Callard’s tale—composed of one part clerical error and one part parental risk aversion—serves as a stark contrast to the “politicized” way that pronouns are thought about today. Instead of having open-ended conversations about them, Socratic explorations of how to apportion respect, the fact of one’s acceptance or rejection of other people’s pronouns defines one’s position in a symbolic contest that supplants the philosophical arguments about the underlying dispute with a competition for esteem between two dueling sides on a contentious social issue—and that, she argues, stands in the way of freedom. Callard is not wrong that “politicizing” disputes about matters of symbolic, communicative significance can get in the way of more direct philosophizing about the laws, rights, and morals that we are actually disagreeing about. But it should also be pointed out that what is at stake in these contests about “justice” and “liberty” is also freedom—whether trans and nonbinary people deserve to be included in our codes and laws of mutual respect, whether they can receive healthcare, and even whether they should exist. These issues, whether they’re being debated directly or indirectly, are not just politicized disputes over abstract matters of language and identification: They are also disputes over material life and over who can and cannot be free to control their body.

In her second chapter on politics, this one only on equality, a similar set of arguments is made. Callard acknowledges that the equality that exists today is “not the real thing,” but the analysis of what the real thing might be, at least in Callard’s book, is scant, to say the least. We are treated to a section on “Egalitarianism in the Iliad,” in which she explains that the dispute between Agamemnon and Achilles over whether to send thousands of soldiers to their deaths in a conflict over the ownership of some particularly beautiful women is a little bit like the thing we are doing when we give out equal slices of birthday cake—at bottom, a showdown about whether each of these men would acknowledge the other as an equal. But we also never get much in the way of discussion about how our social roles, wealth distributions, or rights of travel and relocation might need to be adjusted to fit “substantive equality” (not to mention the challenge it might pose for substantive equality that some of us are having a birthday party and some of us are the cake).

To the extent that they are discussed at all, equality, justice, and liberty are instead framed as conversational achievements. Callard insists that the “proper home of equality and respect” is “the world of the conversation,” a special “inner world” within the larger world that she insists is “elevated above everyday cares,” even above “bodily survival.” But whether and with whom one can arrive at this lofty station depends in obvious ways on the makeup of the “outer world”—the fact that Agamemnon and Achilles were both nobility may not have settled the matter of how they spoke to each other, but it does explain why they were the ones in the room allowed to speak in the first place. A proper appreciation for genuine philosophical engagement may be the best response to an uneven playing field, but Callard gives us no reason to believe that this alone is the path to leveling it.

All of these considerations point to the main reason why we might not want to adopt a Socratic approach to the examined life: that to truly live a philosophical life requires examining social structures well beyond how they show up in conversation. To truly have a philosophical conversation requires, after all, the right environment. One can’t be too hungry or too tired; one needs the time and energy to inquire on an even playing field and a reasonable expectation that one will find willing partners to converse with on terms of mutual respect—exactly the kind of expectation-managed way of recognizing someone else’s pronouns and other codes of symbolic respect. Freedom, even in the “inner world” of conversation, must be understood not only negatively but also positively: To truly be free to converse, one must not simply refuse the strategies of avoidance that were available to Tolstoy but make use of the social resources that were available to Socrates—his status as a free man, a vibrant intellectual culture, and social relationships with friends and comrades. Those things were made available to him not by virtue or by reason but by the circumstances he enjoyed in Athens. These facts point to a set of questions that Callard studiously avoids in Open Socrates.

Interestingly enough, this avoidance strategy also calls into question the book’s larger interpretive ambitions. One could imagine a defense of Callard that insists that all this talk about systemic injustice and the structural barriers to philosophical conversation is merely a “woke” 21st-century revisionism that gets in the way of a serious engagement with the classic texts that Callard discusses here as a scholar of ancient philosophy.

But such a view comes into conflict with what we know about the historical figure she bases her views on. As Callard herself illustrates in a chapter titled “Savage Commands,” Socrates understood the laws and norms of his people as suggestions rather than commands and therefore believed that each individual had to make a set of personal decisions about how to live their life. Neither Socrates’ decision not to conscientiously object to fighting for Athens in the Peloponnesian War, nor his refusal to escape his death sentence after being found guilty of “corrupting the youth,” were performances of duty to reason or to institutions; they were instead performances of duty toward his polis.

Socrates, in the end, died precisely because he did not share Callard’s view of either philosophy or the philosophical life. Confronted with the choice between execution and the pursuit of philosophical questions in exile from the people and culture he loved, Socrates chose death over alienation from his polis. What he considered the philosophical life to be, and what was required to live it, involved a commitment not just to philosophical conversation but also to the complex web of social relationships and duties underneath. One of the most powerful and enduring lessons of Socrates’ life is precisely this: that what one ought to do, even unto death, is inextricably related to questions of connection and solidarity.

We also needn’t confine ourselves to Socrates’ biographical details to challenge Callard’s specific outline for the examined life. We could simply avail ourselves of the plainest readings of the very Platonic dialogues that she engages with—dialogues that involve explicit positions about the ideal distribution of goods and resources, political power, socialization into cultural attitudes and hierarchies, and the connection of each of these with the kinds of philosophical conversations that are possible.

Plato’s Republic, the longest of the dialogues that feature Socrates, is devoted to exactly the questions that Callard avoids. The Republic is explicitly framed around the question “What is justice?” and does not confine itself, as Callard does, to stray observations about divvying up birthday cake. Rather, the participants in this dialogue argue about which of various social structures makes philosophical inquiry possible and for whom. They debate different ways of arranging society, place a few of them in ranked order, and discuss how to square the philosophical life with the fact that they live in circumstances that are much less than ideal—circumstances that require the managerial intervention of politics.

There is also the pesky fact that Socrates had his own prescriptions too. He did not merely ask questions but also offered concrete answers, and one wonders whether Callard is more eager to discuss anodyne abstractions about how philosophical conversations should go than the details of Socrates’ actual answers to some straightforward political questions. Whatever clever interpretations one might try out to explain his reasoning, one cannot entirely escape the fact that in the Republic, Socrates offers an apparent defense of authoritarian censorship and eugenics, while advancing arguments that explicitly portray aristocracy as preferable to democracy. For the Socrates of this dialogue, at least, democratic equality is considered as a problem to be avoided rather than a value to be prized, raising another set of questions about “Socratic equality” that Callard carefully avoids.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →It would seem that our actual social circumstances—not just the ones that are immediately salient in any given conversation—determine whether and for whom justice, equality, freedom, and other central aspects of the philosophical life are attainable. And about these core aspects of the examined life, it is Agnes Callard—not Plato or Socrates—who has nothing to say.

While these points about the source material pose problems for Callard’s argument about how to understand Socrates and his method, what’s more striking is that this avoidance of relating personal philosophical examination to questions of how one exists within larger social structures undermines some of the book’s own imperatives to live philosophically—something that I, too, want more and more people to do.

Callard initially frames her book as a response to a particular depiction of the unexamined life: Confronted with the fear of existential questions, many people live life in 15-minute intervals of things that they busy themselves with. Some of these, Callard acknowledges, involve necessities of some kind: the sorts of activities one might rightfully consider with some urgency, such as “I must go to the store” and “I have to get to work.”

But the sense of urgency that applies to going out to buy food and other necessities, as well as earning the wages with which to afford them, is not the manufactured urgency of a person who hopes to avoid philosophical questions about the meaning of life, but rather the genuine urgency that underpins any workable philosophy on how life ought to be lived: One must succeed at providing for one’s basic needs if one is to succeed at anything else.

More to the point: The differences that emerge in the circumstances of work bear fairly directly on how actual conversations go, as some of Callard’s and my contemporary colleagues (or anyone who ever had a boss) could probably tell you. Again, even Plato seems to have been somewhat reflective about which people were involved in his dialogues as full participants and which were relegated to the role of side characters (like the slave who opens the discussion in the Republic, or the one trotted out to prove a point about ignorance in the Meno), or as objects whose fate would be decided by those whose conversations we’re interested in (the women treated as war prizes or the men treated as cannon fodder in terms of the discussion between Agamemnon and Achilles).

When it comes to Tolstoy, one also has to wonder if this is the same Tolstoy many of us know. Callard holds him up as the archetype of refusal to engage in the examined life. But is this true? Count Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy, the noble inheritor of a 4,000-acre estate and the lord of over 300 serfs, was well aware of the relationship between the time he found on his hands to ask “untimely” questions and the labor of those 300 serfs to create such leisure time. This was part of what made his quandary so profound, and it was also what drove him not only to stasis but, eventually, to political action. He founded a democratic school for peasant children, agitated against the private landownership that had propped up the institution of serfdom, and personally took up labor alongside his emancipated peasants.

Tolstoy saw life and philosophy as intertwined and was fiercely critical of self-obsessed inquiry, including “philosophy adapted to the existing order” that sought only to justify it. True science, Tolstoy contended, would try to answer the ground-level questions about the lives we live: “how the associated life of man should and should not be constituted; how to treat sexual relations, how to educate children, how to use the land, how to cultivate it oneself without oppressing other people, how to treat foreigners, how to treat animals, and much more.” We needn’t endorse Tolstoy’s answers to these questions any more than we need endorse Socrates’. But it is difficult to deny that Tolstoy was, in fact, examining the actual material and political structures that made his life possible, including yet also beyond the conversations he had with the serfs on his estate.

In the time it takes to read this book, we are told much about interpersonal love and equal respect in conversation, but little about picket lines and equal respect in the workplace. Maybe, next time, Callard could examine that.

More from The Nation

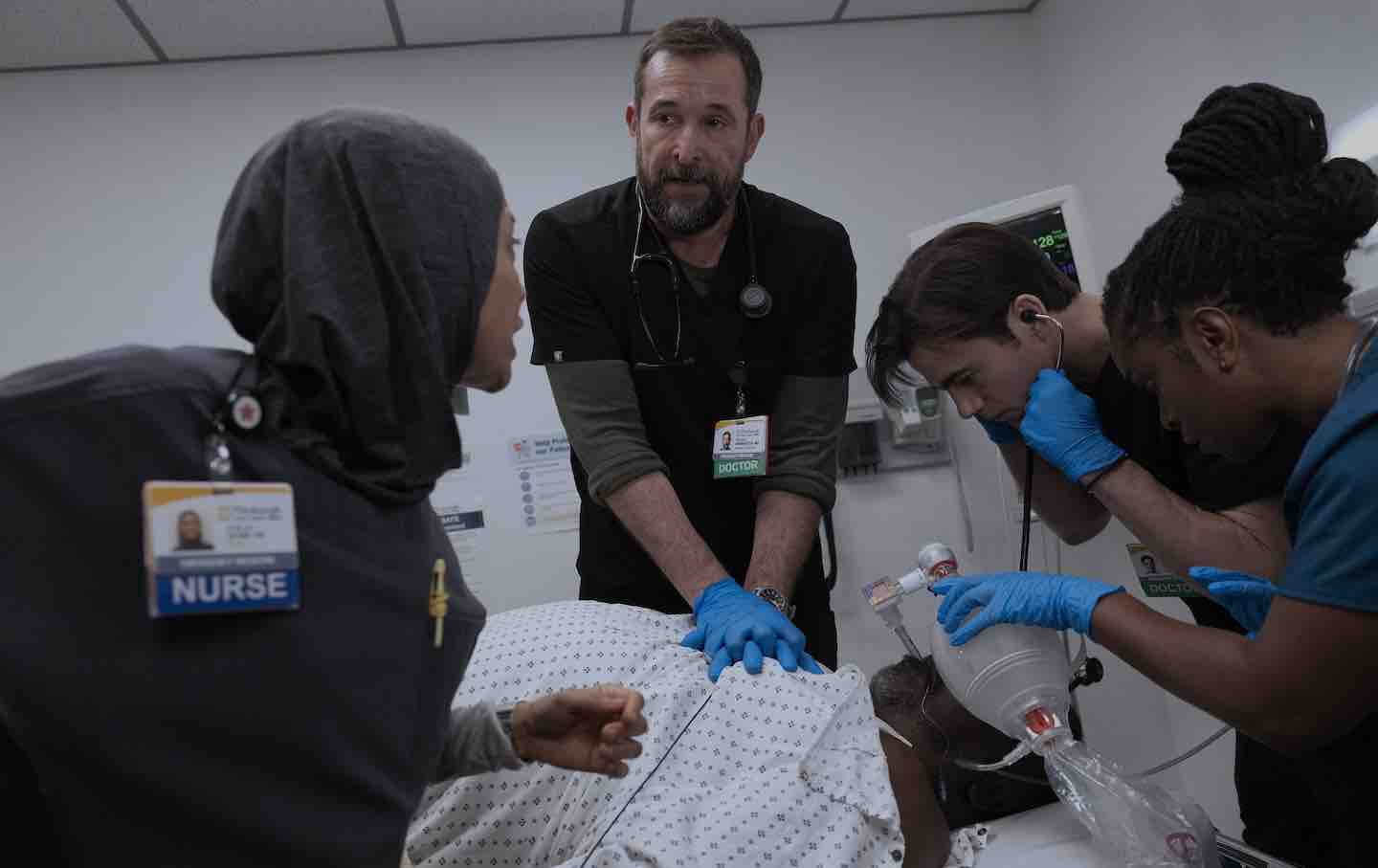

“The Pitt” Shows Doctoring Uncensored “The Pitt” Shows Doctoring Uncensored

The second season tackles everything from the role of AI in medicine to Medicaid cuts. But above all, it is about burnout.

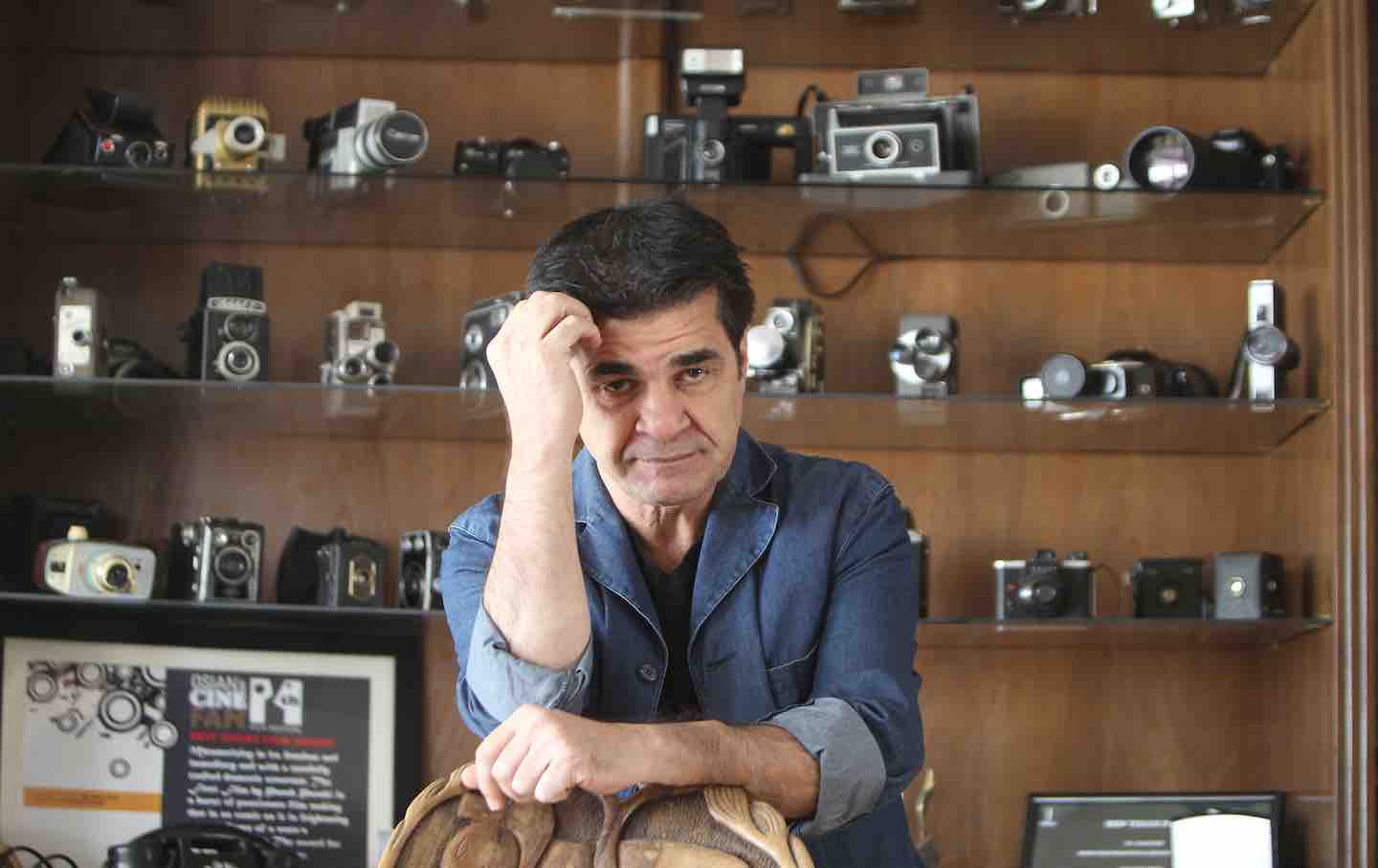

Jafar Panahi’s Scenes From a Crime Jafar Panahi’s Scenes From a Crime

His films show how a regime’s wrongdoing can upend one’s sense of self and transform the very rhythm of daily life.

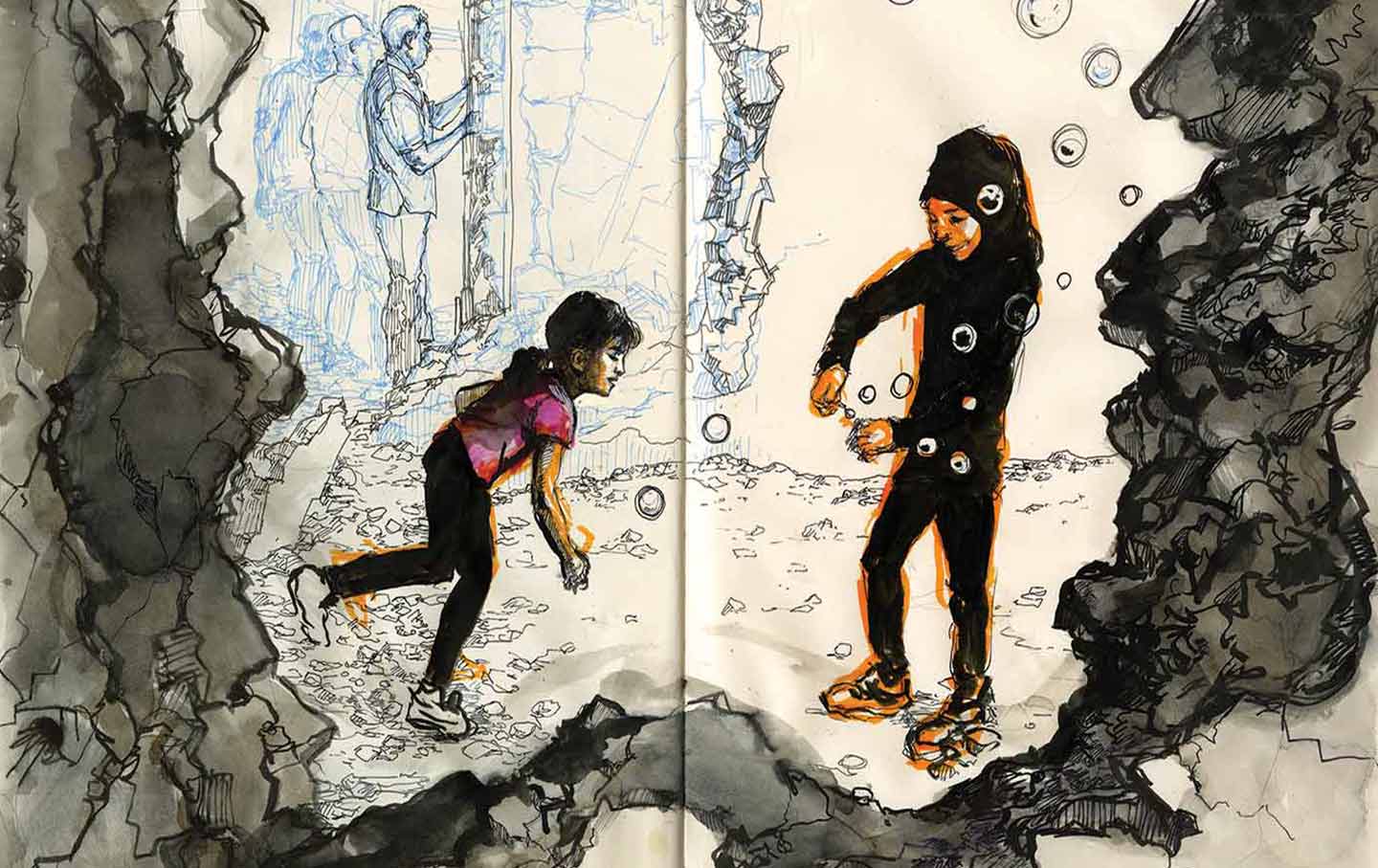

Molly Crabapple's Time Capsule of Resistance Molly Crabapple's Time Capsule of Resistance

A new set of note cards by the artist and writer documents scenes of protest in the 21st century.

The Exposure Therapy of “A Private Life” The Exposure Therapy of “A Private Life”

In her new film, Jodie Foster transforms into a therapist-detective.

The Riotous Worlds of Thomas Pynchon The Riotous Worlds of Thomas Pynchon

From “The Crying Lot of 49” to his latest noirs, the American novelist has always proceeded along a track strangely parallel to our own.

Letters From the March 2026 Issue Letters From the March 2026 Issue

Basement books… Kate Wagner replies… Reading Pirandello (online only)… Gus O’Connor replies…