In the Cuban-Italian novelist’s Her Side of the Story, she confronts the falsity of romantic love.

In The Second Sex, her 1949 feminist polemic, Simone de Beauvoir declared romantic love, as we’d known it for centuries, a sham. Neither women nor men thrive in the conventional arrangements of coupledom and marriage, but it is the woman in love, de Beauvoir asserts, who “creates a hell for herself”: Society, and its patriarchal degradations, obstruct the possibility of her equal happiness. To love a man under these circumstances is a congenital torment, an internal organ mangled from its first growth. Love’s flame, as it were, burns brightest in hell.

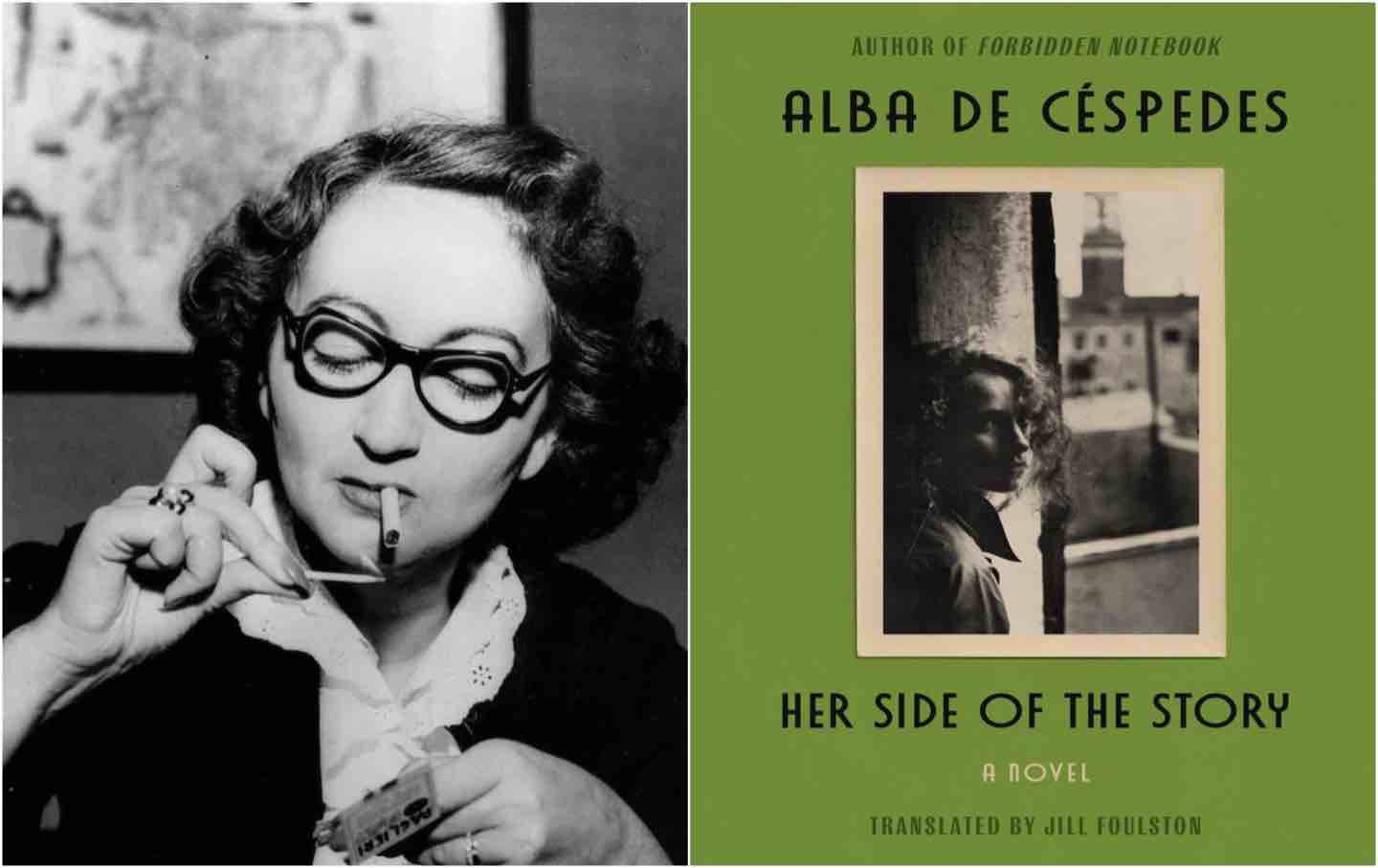

De Beauvoir is indisputably the most prominent feminist figure to establish herself in postwar Europe, but she was not, of course, the only writer coming to stern conclusions about the kinds of romantic and sexual possibilities available to women. The first volume of The Second Sex was published in June 1949, and in August of that same year, the Cuban Italian novelist Alba de Céspedes published Her Side of the Story, a work propelled by a vigorous critique of the institution of marriage. De Céspedes dramatizes the dilemma of women’s happiness theorized by de Beauvoir through a coming-of-age narrative culminating in the dreadful fallout from one young woman’s romantic disillusionment. Told in retrospect by a woman named Alessandra Corteggiani, the novel weaves a circuitous path through her memories: from girlhood, when she first devotes herself to the pursuit of a perfect love, to the lank, lonely marriage that desecrates her hopes.

Women, Alessandra surmises at the precocious age of 16, “seemed…a gentle and unlucky species…weighed down…by a centuries-old unhappiness, an inconsolable solitude.” The events of the novel, which begins just before World War II and concludes soon after the fighting in Europe ends, will do little to change her mind, for Alessandra’s side of the story doubles as de Céspedes’s sweeping and implacable jeremiad against marriage. Alessandra experiences matrimony as a state of psychological alienation, its promises of loving attachment rendered impossible through the inevitable reality of her subjugation.

Her Side of the Story, recently reissued in a new English translation by Jill Foulston, was first published in English in 1952 as The Best of Husbands, a title that reveals itself to be darkly comic by the novel’s end. This was not the name that de Céspedes, who had already attained literary prominence in Italy, had envisioned for the work, which she intended as both her magnum opus and her feminist apologia. Initially, she had planned to call it Confessione di una donna (Confessions of a Woman), and indeed the very point of this story is to explain the basis for the “horrible, cruel,” and, for the brunt of the novel, undisclosed act that Alessandra has committed.

Alessandra might be characterized as a proto-feminist rebel, a young woman determined to know love on her own terms; she does not, at first, strike the reader as a person easily vanquished by social ills. These qualities of philosophical conviction and resilience are crucial to de Céspedes’s aims: Like de Beauvoir, she depicts heterosexual marriage as an utterly incapacitating arrangement that decimates a woman’s sanctity of mind through its curdling of romantic ideals. The key to a woman’s self-preservation, we learn by the end of the book, is not merely to reject marriage but to reject the promise of happiness touted by a society that thrives on her oppression.

“Imet Francesco Minelli for the first time in Rome, on October 20, 1941,” Alessandra tells us at the start of the novel, establishing its testimonial tone. Francesco, the reader learns, is Alessandra’s husband, a much older academic who, during the war, participates in Italy’s underground movement against fascism and later becomes an admired public figure. When Alessandra first meets him at a gallery opening in Rome, she is a lonely university student who falls swiftly in love.

But de Céspedes has no interest in telling her readers a love story, and Alessandra quickly moves from meeting Francesco to a thorough account of her formative years. He will return to the narrative in context, some 250 pages later, when Alessandra, now firmly established as the protagonist, begins recounting her experiences as a college student in Rome. De Céspedes anticipates her readers’ skepticism patiently—why this long deferral?—albeit with a show of defensiveness on Alexandra’s part. “It occurs to me sometimes that I’m going on too long about what happened before my marriage to Francesco,” she says early in the novel. “But surely no one would know anything about me, about my character, and who I am, if I silently skipped over the way I lived and what I felt then.” This justification implies the novel’s underlying assertion, which situates it within a larger tradition of feminist first-person narratives: Women’s interiority is not incidental but rather pivotal to how we make sense of the world.

It is fitting that de Céspedes prioritizes female subjectivity in her work, for in life she privileged her own aspirations. Married to a diplomat, she remained at home with her work when her husband was away on postings. She was, moreover, an intrepid participant in Italy’s anti-fascist movement and was jailed more than once for her activism. Yet her background was also one of obvious social advantages: Her grandfather was the first president of Cuba, her father an ambassador. Her feminist politics, however outspoken and earnest, developed against a backdrop of class privilege and alongside powerful male kin. It’s perhaps no surprise, then, that in Her Side of the Story, Alessandra’s misandrist tendencies are markedly class-inflected. She is most unsparing in her assessment of men with whom she shares few intellectual or temperamental affinities. Yet as Alessandra comes of age and meets men with more refined sensibilities, her perceptions soften.

De Céspedes’s readers are privy to these distinctions because we are also privy to the whims of her narrator’s restless psyche. Like de Céspedes’s later novel Forbidden Notebook (1952), Her Side of the Story demands an acute intimacy between narrator and reader. But in the latter, Alessandra stipulates this closeness; in the case of Forbidden Notebook, we are voyeurs, peeking over the shoulder of the protagonist, Valeria Cossati, as she scribbles in her hidden diary. Often on the verge of destroying her notebook, Valeria is seeking not the chance to communicate with posterity but the opportunity to bear witness to herself. Still, she wonders if she ought to have begun writing in the first place.

Alessandra, by contrast, cannot seem to stop writing; she is animated by a conviction of her own significance. Her autobiographical reminiscences follow the path of exhaustive detail: She recalls her early life in Rome, before her mother’s death; then her brief residence in Abruzzo, where she lives with her paternal relatives; and finally her return to Rome at the start of the war, where she marries Francesco and sets up house amid air raids and the Nazi occupation.

More circuitous than these geographical movements are the story’s maneuvers through Alessandra’s turbulent consciousness. Her recollections spill eagerly and abundantly, and her capacity for empathy is often short-circuited by this assiduous introspection. One gets the impression of a young woman who has relied so thoroughly on the provisions of her own mind that she cannot conceive of other interiorities beyond her own.

Alessandra might interpret this tendency as reactive, an overcorrection born from the early “suppression of [her] personality” inflicted by her parents. Shortly before she was born, her brother, Alessandro, drowned in the Tiber. Bereft, Alessandra’s parents imposed on her the role of proxy son who fulfills her brother’s destiny in his stead. Alessandra, in turn, believes herself inhabited by her brother’s ghost, though she rejects her parents’ idolatry. She instead “attribute[s] an evil power” to Alessandro, whose spirit has compelled her to indulge in “wicked thoughts, and unwholesome desires.” Alessandra eventually understands that Alessandro’s oppressive specter is, in reality, a receptacle for the sexual curiosity she repudiates but cannot extinguish. Nevertheless, her fractured identity and its insinuation of an essential, gendered difference provide the foundation for her quixotic views on men, which intensify under the threat of disproof.

From an early age, Alessandra is repelled by the sleazy, bourgeois masculinity embodied by her father and his friends. She thus decides that fiction, rather than real life, offers more genuine depictions of the gender. “I didn’t dare believe that these were truly ‘men,’” she writes, for books “had taught me very different things about them…. I sometimes felt a furious desire to get away from [my father and his colleagues], to chase them away, so that my dream…wouldn’t die.” Over the course of her adolescence, she nurtures this dream of a man who embodies more poetic sensibilities. She first fixates on a friend’s brother, whom she never meets and who has been imprisoned for being a communist. Later, disturbingly, she falls briefly in love with her paternal uncle, a bachelor 30 years her senior.

These, ultimately, are impossible desires to fulfill. Indeed, de Céspedes seems keen to emphasize the impossibility of all of Alessandra’s romantic desires, whether they are born from a rational expectation of equitable love or, instead, are the stuff of storybook fantasy. What’s impossible to determine is the root of Alessandra’s anger: Is it the perpetual indignity of life under patriarchy that feels most untenable, or is it men’s inability to perform the chivalric masculinity for which she yearns?

De Cépedes suggests that the latter is exacerbated by the former. In girlhood, Alessandra observes the bleak drama provided by her neighbors’ comings and goings: the “cruel and selfish” philandering husbands who “never had a thing to say to the women,” and the dreary domesticity endured by the wives who keep house and, now and then, seek succor in their own infidelities. Her father, Ariberto, is contemptibly “mediocre,” sneering and bullish, “an insidious enemy” who “invaded [the] cozy feminine world” shared by Alessandra, her mother, their housekeeper, and the few friends they admit into their orbit.

It is Alessandra’s mother, Eleonora, who mentors her on the fraught subject of romantic love, ultimately by the tragic idealism of her own example. When Alessandra is 17, Eleonora falls in love with a piano pupil’s older brother and begs Ariberto for freedom from their unhappy marriage. Despite his persistent womanizing, Ariberto refuses, and Eleonara drowns herself. Through her death, she bequeaths to Alessandra a symbolic refusal of “mediocre love” and, in turn, her dedication to its consummate form. In the years that follow, Alessandra speaks of her mother’s suicide with hushed reverence. She regards it not as a warning but as an example of idealistic rigor and the sacrifice that true love deserves.

De Céspedes wants her readers to perceive the danger in Alessandra’s convictions, and yet Her Side of the Story denies the possibility of promising alternatives. Alessandra could marry the pleasant, respectable family friend proffered by her grandmother in Abruzzo—but she doesn’t love him. “I believe love is something else,” Alessandra objects. “You’re mistaken,” her grandmother retorts. “All men are alike. They say the same things and do the same things.” The exchange lays bare the novel’s great quandary: A woman is entitled to believe in the extraordinary particularity of love and to marry, if she wants, but the damage wrought by this hapless pursuit is of her own making. The novel undergirds what Alessandra’s Nonna states outright: How could love be singular when no man is?

At first, Alessandra believes that Francesco is an exception. He seems eager for the same mutual loving union that she seeks, and by all appearances, his political beliefs make him an ideal partner for an independently minded woman. They marry, and she loves him with an obsessive, almost deifying devotion. (“Oh Francesco, Francesco,” she grows accustomed to thinking to herself.) Francesco accepts Alessandra’s worship as his due—he, too, believes himself exceptional—and in return offers the wan, distracted companionship of a man whose priorities do not include his spouse.

Alessandra is desperate to convert their marriage into the idealized love of which she has dreamt, but she cannot penetrate Francesco’s sexism and condescension. When he is taken as a political prisoner, she imagines that the prison wall assumes his form, torturing her with reminders of his detachment. It “resembled Francesco’s eyes, which never responded to me,” she recalls, “it resembled his impenetrable shoulders, behind which I lay awake at night, crying.”

The two never achieve common ground. Alessandra longs for Francesco, but not as he exists; she wants, instead, the specter she has conjured from her teenage daydreams. Meanwhile, Francesco sleeps easily in the shadow of his wife’s anguish. To her pleas, he responds, “I love you, Alessandra. Our marriage is a happy one.” These are some of his last words in the novel.

Eventually, we realize that Francesco has died prior to the story’s telling, although Alessandra invokes him in the present tense. Her husband’s death creates an absence readily filled by the ghost from her fevered projections: a Francesco who, unlike his deceased counterpart, returns Alessandra’s adoration. The best of husbands, de Céspesdes insinuates, is a delusion, summoned to soothe the psychological wounds sustained in marriage.

But what happened to Francesco? What has Alessandra done, and where has she gone? The novel’s grim climax and denouement furnish readers with the desired revelations, although one will not be too surprised by them. For her part, Alessandra is indifferent to her current situation. She has achieved her purpose: to be a woman whose story is known, to lay bare her love of one man and to chronicle the toll that love exacted. “I believe that the story we intend to leave behind is the secret motivation of our words and acts,” she writes, “you could say it’s what we live for.” In the meantime, her story offers no certain future.

“If I don’t succeed [in being happy with Francesco], I’ll kill myself,” Alessandra vows soon after their wedding, still committed to her mother’s devastating idealism. Eventually, Alessandra comes to realize Eleonora’s fatal philosophical error: “I could reproach [my mother] for having subjected me to that climate of perpetual exaltation, which, above all, made me completely devoted to the myth of Great Love, if she hadn’t already paid for her ambitions.” De Céspedes’s warning here looms large: Expecting too much from men can be a deadly enterprise.

Rachel Vorona CoteRachel Vorona Cote is a freelance critic and the author of Too Much: How Victorian Constraints Still Bind Women Today. She lives in Takoma Park, Maryland