A few months ago, when the pandemic was still young, the literary question du jour was who would be the first to write the great American Corona novel, or which notable person of letters might already be at work on such a project. This speculation, by no means unique to the coronavirus or to our present moment, emerges from a conception of literature as a kind of report on worldly circumstances. By this account, the author experiences the world, often engages in research, arranges and shapes the material, and reports back. At its most reductive, the expectation takes us all the way back to Stendhal: “A novel is a mirror carried along a high road.”

To be clear, there are many successful works of literary art that set out to respond to epoch-making events and eras. Rachel Kushner’s The Flamethrowers (the 1970s in New York City); Emma Cline’s The Girls (Manson-adjacent California in the 1960s); Rebecca Makkai’s The Great Believers (Chicago during the AIDS epidemic), and Colson Whitehead’s The Underground Railroad, to name a few recent examples, certainly transcend reportage, and do so with varying degrees of fidelity to the letter of history. But another kind of novel, by resisting depiction and explication of the disaster and absorbing the culture of disaster itself, belongs to the category of the prescient, analyzing history in advance, as it were.

Blake Butler’s new novel, Alice Knott, was written well before the emergence of Covid-19, yet it resonates so strongly with life under lockdown that one would be forgiven for thinking otherwise. The narrative is filtered through the obsessive consciousness of the titular character, an aging heiress who “hasn’t left her house in years.” Alice’s basement vault is filled with priceless works of art that she hardly looks at anymore, and her main sources of diversion are what occurs on various electronic screens. When vandals break in and destroy her art, a video of the act goes viral, causing an international sensation as masterpieces around the world are targeted. Already isolated and ruminative, Alice unravels further as she becomes embroiled in the criminal investigation and derailed by her hurtful introspection.

The world of the novel is of a piece with lockdown existence in the sense that its reality is largely recognizable, although distorted and intensified. No one can say what life will look like post-pandemic, but existing trends that appear to be accelerating include time spent online, the further consolidation of corporate power, and social atomization. When Alice sees the act of vandalism in her home reported on the TV news, for instance, it is described as “presented tonight alongside advertisements, scores, and weather, all of them wearing our attention down, molding our position into a feed we can nurse through our adult lives.” The feed evokes the character of social media, and is followed by a “tumult” of broadcasts in which “dozens or hundreds of public personalities” produce content unconcerned about “what had actually occurred” and that instead seek to construct identities and reality itself.

Alice’s reaction to seeing herself on television applies, as well, to our increasingly online life. “That couldn’t be what she looks like to other people, could it?” she muses. When Alice thinks, it seems to be in a voice “not wholly hers.” Having quit drinking, she is “smashed no longer on gin and water but on her impression of the present as ongoing event, suspended between the conflicting impressions of isolation and surveillance at the same time.” Alice Knott captures the affective experience of being physically alone with the screens that remedy and magnify this condition, and in doing so eerily anticipates the accelerant to come in 2020. Alice’s alienation is both technological and cognitive, as well as evidence of the novel’s commitment to an aesthetics of absence: Her memory is full of holes, her childhood colored by the disappearance of family members (later replaced by an “unfamily”), and her thoughts tend to undercut themselves, at times bringing her own selfhood into question.

If here’s a positive aspect to any of Alice’s thoughts, it would be found in the realm of art. Though priceless artworks are the target of the wave of destruction, Alice repeatedly praises their specialness not as beyond price but as one of a kind. The fragility of these works is what differentiates them from the endlessly proliferating viral fodder on offer. Furthermore, their destruction hints at actual creative potential. In the account of the first viral video, the incineration of Woman III by Willem de Kooning is characterized as follows: “The destruction is beautiful itself, too, some viewers will argue, in its own way.”

Besides the interplay between image and text, Alice Knott is concerned with the sonic, as when masked figures in the viral video take the painting off the wall, there is “no sound but the low, ambient buzz of a hot mic recording nothing.” This is surely a reference to John Cage, a quote from whose “Lecture on Nothing” serves as an epigraph to Butler’s 2011 memoir Nothing: A Portrait of Insomnia. Cage’s well-known music of silence has analogues in monochromatic art, such as Rauschenberg’s White Painting (part of Alice’s collection), and the Samuel Beckett of Stories and Texts for Nothing and Nohow On.

Alice Knott represents a continuation of this aesthetics of the void and a contemporary instance of making art out of emptiness. For what embodies absence more completely than a white painting—a white painting that’s destroyed? In a way that recalls Butler’s memoir about his struggles with insomnia, Alice Knott itself is a powerful rethinking of absence’s aesthetic and political dimensions. For the insomniac, as for the recluse and the quarantined, time is evacuated of meaning. The interior spaces of both Alice Knott and Butler’s memoir are similarly distorted: endless hallways, personal disorientation, and a kind of dream logic that has Alice “arriving back to where she’d already been” after walking exclusively in one direction.

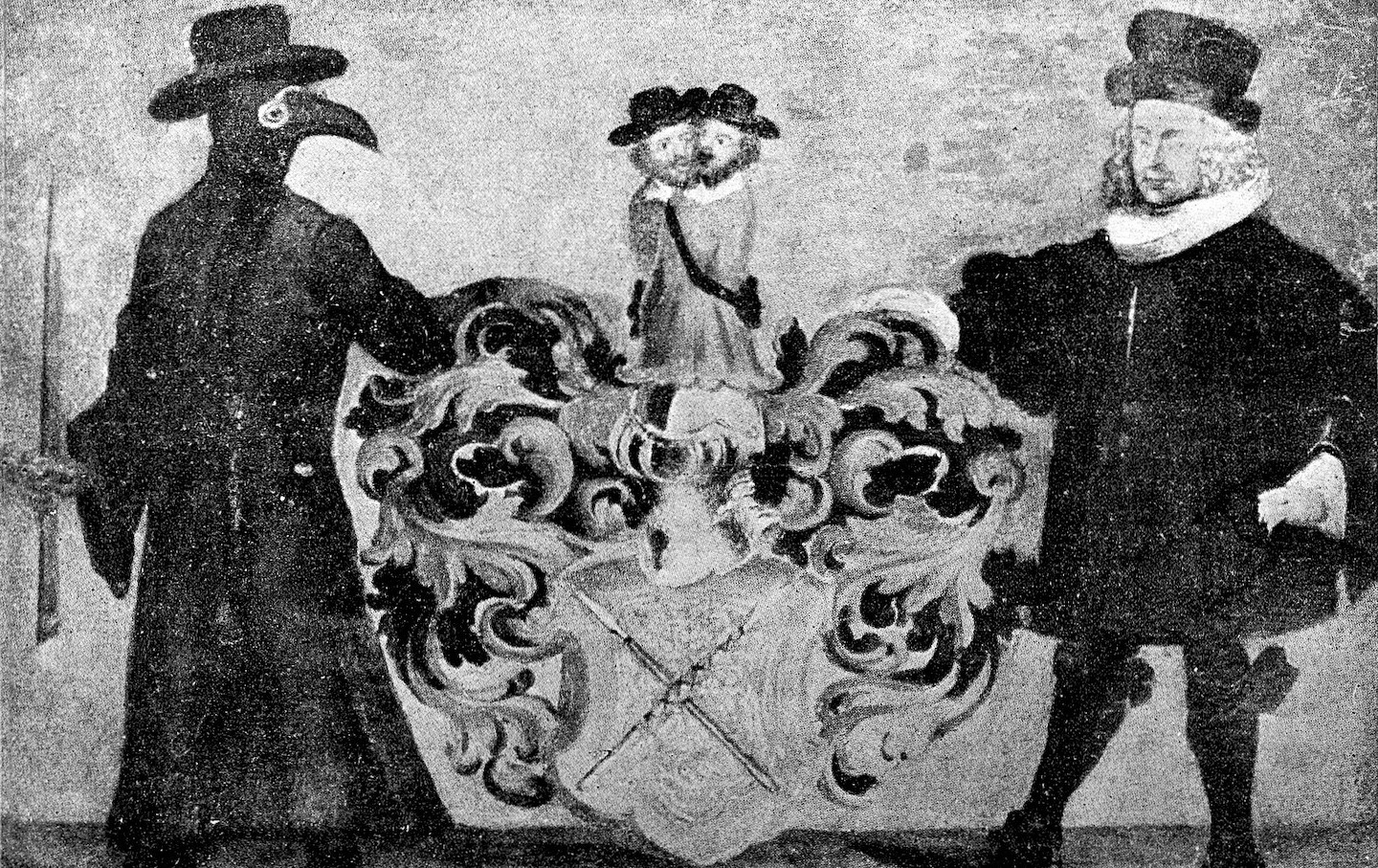

In addition to an overwhelming defamiliarization, a sense of illness defines the world of the novel. Alice is barred from contacting her so-called “unbrother” (who in the strictly Freudian sense uncannily resembles her) as he is “under quarantine,” and there is a brief mention of “a virus passed by sight” as well as a set piece concerning “an epic plague.” To put things in perspective, Butler’s work has visited destruction on humanity for over a decade: from the plagues of his early novel-in-stories Scorch Atlas to his 2014 novel 300,000,000. The latter title refers to the population of the United States, which is ravaged by mass hysteria.

Just as 300,000,000 imagines the end of America, there’s a way in which Alice Knott imagines the end of art, or art’s final form. Oddly enough, Butler’s long-standing focus on America’s (often self-inflicted) suffering finds its eeriest expression in a passage from Alice Knott concerning the memory of a popular television drama “centered on a retelling of the foundational history of the United States.” This virtuosic scene runs for seven pages over which the novel’s strands of media, art, and contagion converge. Here’s the kicker. While watching this dramatic serial with her family as a child, Alice believes she is actually watching the news, “captured footage of real living people.” In a mirror inversion, unlike Alice, who thinks what she’s watching is true though it is fiction, readers expecting fiction from this novel will be met with an echo of reality. The series, whose name Alice cannot recall, “depicted crime and turmoil during the fallout of an epic plague that deconstructed all emotional logic, and then nostalgia, then all the rest.” The plague is a psychic one, “a continuously mutating viral fire feeding off human experience,” a virus contracted by watching the series itself and avoided only by refusing to watch.

To watch this fictive television show is to “eradicate all sense of self from those exposed,” much in the way those who encounter the eponymous film in David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest begin to drool, soil themselves, and neglect to eat, viewing it on repeat until they expire. Yet whereas much of the anxiety driving Wallace’s novel takes the form of film and television’s cultural dominance, the rivals facing Alice Knott have multiplied to include the Internet and an increasingly oppressive 24-hour news cycle.

Ultimately, Alice Knott is disturbing because it is familiar. Alice spends her days indoors looking at screens, but so do we, and most of us can’t blame it on agoraphobia. In fact, though an unspecified cognitive disorder is mentioned, I would hesitate to attribute Alice’s mental state to anything other than modern life, such as it is. In terms of the unnamed show above, reading about it gives rise to the novel’s ultimate allegory. As fiction mistaken for news, it reflects the ongoing process of journalism detaching itself from reality as fiction increasingly merges with history and biography. Indeed, the perverse logic of Alice Knott often provokes the same question that watching the news in 2020 tends to provoke: How real is this?

Brooks Sterrittis the author of the forthcoming novel The History of America in My Lifetime. An assistant professor of English at the University of Houston-Victoria, he has written for The New Republic, The Believer, and other publications.